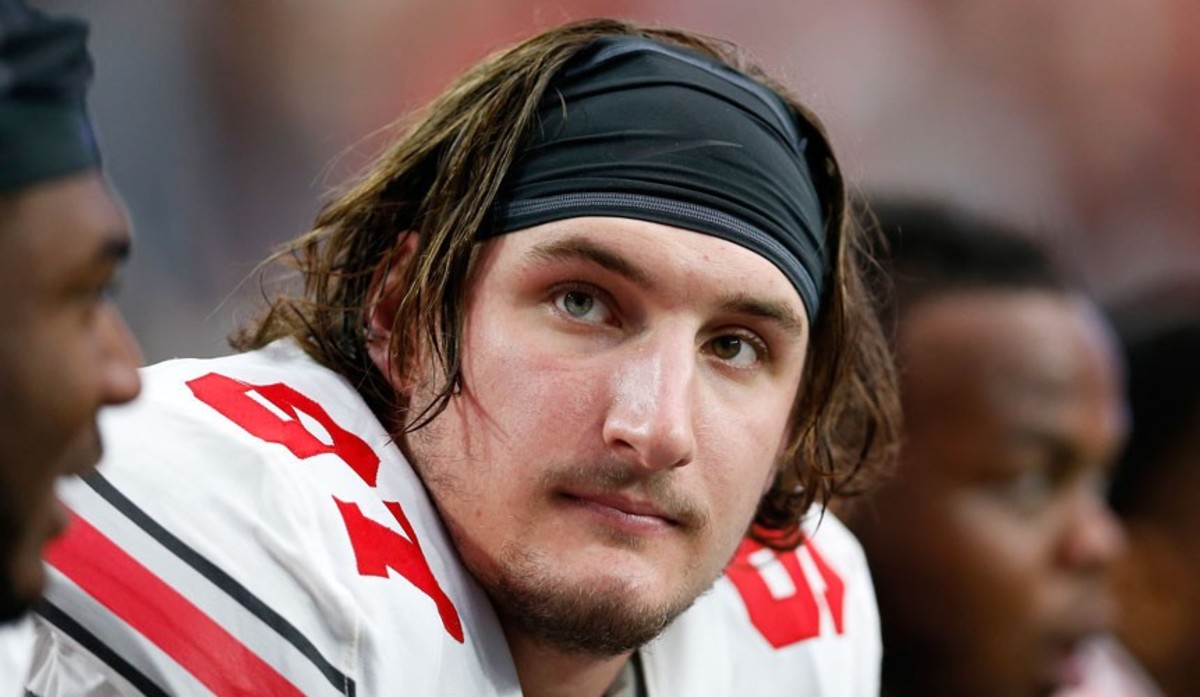

Joey Bosa's disappearing act: Why the Ohio State star spent last fall in solitude after an off-season mistake

[video:http://bcove.me/w1ka8j5d]

SCOTTSDALE, Ariz. — Last spring, Cheryl Bosa boarded a flight from Florida to Columbus, Ohio. She and her son were going apartment hunting.

It was a strange time for a college student to move, and stranger still what the two were looking for: a one-bedroom place, quiet, apart—for a football player about to turn 20 in July, who by then was already talked about as a potential top pick in the next spring's NFL draft, who should have been the biggest big man on Ohio State's campus.

But last spring, defensive end Joey Bosa and three of his teammates violated the school's Department of Athletics Policy. (News of the transgressions, which ESPN reported as being related to marijuana and academics, came down on July 30 to the public. Bosa has not commented on the nature of his violation.) The three Buckeyes learned that they would be suspended for the defending national champion Buckeyes' first game of the 2015 season, an eventual 42–24 victory at Virginia Tech on Sept. 7, and three of the players apologized before continuing their lives essentially as they were before.

The fourth did not.

The fourth was Bosa, who, after he learned of his violation, spent hours talking with his parents, Ohio State defensive line coach Larry Johnson and head coach Urban Meyer about the magnitude of his suspension. One bad decision could cost a player like him millions of dollars. Another could derail his career. Everyone involved stressed to Bosa that if he wanted to be different, if he wanted to live up to his immense potential, he would have to make changes. "There were hundreds of conversations with his family and him," Meyer recalls. "I've coached premier players, and he is a premier guy. He needed to lock it down. He did."

Bosa says it was his idea to move out of the apartment he shared with Buckeyes tailback Ezekiel Elliott, a close friend who had been his roommate since freshman year. Elliott, though disappointed, understood. There needed to be zero temptations, zero distractions. "I just thought separating myself—not from Zeke, but just from pretty much everybody in general—and being able to control who goes in and out of my life, I just thought it would be a smart idea to lay low for a while," Bosa says.

It was. Living alone and keeping largely to himself, Bosa earned consensus first-team All-America honors in 2015 after making a team-leading 16 tackles for loss, including five sacks. Ohio State, meanwhile, went 12–1 and ended the season ranked No. 4 in the final AP poll. On Dec. 31, a day before the Buckeyes' 44–28 victory over Notre Dame in the Fiesta Bowl, Meyer announced that the defensive end would forego his final year of NCAA eligibility to enter the 2016 NFL draft—a decision that will push Bosa even farther into the spotlight he has spent the last few months ducking.

*****

Christian Petersen/Getty Images

Bosa speaks slowly and deliberately, a surf bum trapped in a lineman's body. He seems almost permanently relaxed, and despite the freakish athletic talents he has possessed since childhood, he has never been one to seek the limelight. As a kid, Bosa was both shy and fiercely competitive, his father John Bosa says, and not much has changed since. John says that when his son learned of his suspension, realized he'd let down his family and his team, the then 19-year-old's personality took over. He was emotional, but also resolved. He was going to beat the suspension, even if to the rest of the world it would look as if he was retreating.

Bosa's personality made the change—nay, the disappearance—easy. In the aftermath of Ohio State's run to the inaugural College Football Playoff national title last January, the Buckeyes' celebrity status in Columbus skyrocketed. Players couldn't go out on High Street near campus without being mobbed, and it was hard for even the most reserved members of the team to avoid getting caught up in the furor of it all. How could they not? Then, of course, came the consequences: the four preseason suspensions, another (to sophomore cornerback Damon Webb) in early September and redshirt junior quarterback J.T. Barrett's DUI charge and one-game suspension in October. Ohio State's players were widely regarded as the bad guys on the field and faced scrutiny after starting slow with closer-than-expected wins over Northern Illinois (20–13 on Sept. 19) and Indiana (34–27 on Oct. 3). Off it, things weren't much easier.

"It's been a long year, been a long career, lots of ups and downs," Bosa says. "But if it's all good, it's not fun. It's amazing all the adversity this team has been through, with losses and people getting in trouble."

It was a climate from which Bosa found it easy to step back. His sparse apartment was furnished with little more than an Xbox, DVDs, football gear, clothing, cooking utensils and the minimum amount of furniture. But he was comfortable, and there was no pressing temptation for him to join the fray. For the entirety of last spring and summer, Bosa spent much of his time alone, cooking Italian dinners from recipes his mother had taught him and playing video games to pass the time. He had never really enjoyed the hassle of going out in Columbus anyway. Heads turning, girls clamoring, fans chatting—none of it has ever truly appealed to him.

"You'd rather people be recognizing you than not recognizing you," Bosa says, "but I never liked going out in public and being stopped every 10 minutes. I like doing my own thing.

"I never really loved being in the spotlight. I was never that kind of person. I pretty much like sitting in my apartment, being in a dark cave for hours. If I spend the whole day there, I have no problem with that. I've got a tight circle, and I'm not really letting a lot of people into my life."

Bosa shied away from inviting friends to his place for months. Eventually, though, he began to relax those rules. He would have fellow lineman Joel Hale over to cook, and Elliott to watch Game of Thrones. Asked how he knew he was able to nudge the boundaries he had set, Bosa answers with conviction. "I realized that I could control myself," he says, "and not make another bad decision."

Bosa's decision paid off. The Buckeye's first game of 2015 is now a distant memory, and while curbing any off-the-field erraticism in his life, he also learned to play more within the Ohio State system, taking fewer chances on the field—or perhaps just taking the right ones. While Bosa's numbers were down from a year ago (his 51 tackles, including 16 for loss and five sacks, don't quite stack up to his 55 tackles, including 21.5 for loss and 13.5 sacks, from '14), that was in large part a result of the extra attention he was getting from opposing offenses. The disruption he brings on the field, coaches and teammates say, cannot be quantified, and foes would spend days game-planning for him.

"He creates pressure on pretty much everyone he's gone against," says Notre Dame offensive tackle Ronnie Stanley, another presumptive first-round NFL pick next spring. "I guess he doesn't [always] get the sack, but the pressure's still there. He's definitely creating chaos."

There may be no better example of Bosa's effect on the defense than in the Fiesta Bowl on Jan. 1, when he started out of position, inside at tackle, due to suspensions and injuries along the Buckeyes' line. Bosa was in the game for just two complete drives—when the Fighting Irish gained just 38 total yards—before being ejected for a targeting hit on quarterback DeShone Kizer. Notre Dame looked as if it might not score at all, but following Bosa's departure with Ohio State up 14–0, the Fighting Irish managed to keep pace with the Buckeyes for much of the rest of the game.

That came as no surprise to any of the 71,123 spectators at University of Phoenix Stadium. All season, Bosa was the lynchpin of the Buckeyes' defense. He has faced double-teams since his sophomore year, and on Nov. 14 Illinois went so far as to triple-team him on one memorable third-down sequence. Fighting Illini offensive linemen Ted Karras and Christian DiLauro and tight end Andrew Davis swarmed Bosa, which only served to allow two Ohio State defenders to get hits on quarterback Wes Lunt, who eventually threw the ball away. That play—three against one, two quarterback hits—perhaps best shows Bosa's impact this season; though he didn't log a single statistic, he was the man most responsible for forcing Illinois to punt.

As GIFs of the triple-team popped up across the Internet and college football continued to sing Bosa's praises, the junior remained largely oblivious. Though he maintains an infrequent presence on Twitter and Instagram, Bosa says he stays out of online conversation surrounding his team and his play. Any conjecture he hears comes from teammates in the locker room—the most crowded social setting he faced last fall.

*****

Come the first round of the NFL draft on April 28, Bosa has a shot to go first overall to the Tennessee Titans, and the end of his college career has spurred a kind of reflectiveness in his father, himself a first-round pick at defensive tackle out of Boston College in 1987. John says that he pushed his sons (the younger, Nick, is a five-star defensive end recruit who will play at Ohio State next season) away from football for as long as possible. They played every other sport first, but ultimately he couldn't keep them from the game. Once they started, there was no stopping them.

John can't quite articulate why he avoided putting his sons in football for so long, but he is aware of how the game has shaped his older son's life. "It's going to be different for you, Joey," he told his older son more than once. "I have said things like, 'Joey, it's important for you to understand that you're not a normal 19-year-old,' " John says. " 'You cannot act like a normal 19-year-old. You cannot do that.' "

It's kind of sad, John admits, that Joey couldn't just live. He has had to live football and football alone, ever since he was a freshman starting on the Buckeyes' line—and before that, really, at a high school, St. Thomas Aquinas in Fort Lauderdale, with a football program as intense as the ones at some colleges. It's sad, but it's a blessing, John repeats.

Eventually, he hits on a word: normal. His oldest son's past three years have been anything but. Joey knows this. When he talks about peeling back the layers of solitude and letting his close group in, he describes it as "getting back to normal." Then he corrects himself. "It's back to—not normal, but people are over."

And that is the crux. Bosa's junior-year experience wasn't normal. It might have been sad. It was probably also necessary to get him to where he is today, and more importantly to where he wants to be, in position to become a top pick in the upcoming NFL draft. He is a ghost until he takes the field, and to say that what he accomplished this season was difficult doesn't even scratch the surface.

Meyer says that retreating from the spotlight would be difficult for any college football standout, let alone one as prominent as Bosa. "I think it's harder than most people give it," he continues. "I respect it.… I wouldn't say it's impossible."

The coach pauses.

"But it's close."