Arc Madness: Three-point rate is at an alltime high, but can a team dependent on the deep ball win a title?

This article originally appeared in the Feb. 15, 2016, issue of Sports Illustrated. It has been updated to reflect the most recent statistics and developments. Subscribe to the magazine here.

The Lloyd Noble Center, Oklahoma's 41-year-old basketball arena, is a concrete island in the middle of a parking lot sea, set far enough from other campus buildings that on nongame nights, one of its practice gyms can secretly double as the most deafening and exclusive dancehall-reggae club in Tornado Alley. On a Thursday evening in late January it's a club for one dancer only, and his name is Buddy Hield, aka Buddy Love, of Eight Mile Rock on Grand Bahama Island. He's in a slow-motion swagger, with low steps and shoulder dips, chopping the air with his right hand, holding a basketball aloft with his left—a few beats of celebration for the Sooners' senior shooting guard after sinking more than 80% of his three-pointers over the past half hour.

Hield is also the deejay; his iPhone, which is playing a SoundCloud mix that includes sirens, horns and tracks by Popcaan and Vybz Kartel, is plugged into a stereo receiver on a rack in a corner of the gym. A yellow arrow with VOLUME LIMIT handwritten on it is taped next to one of the receiver's dials, indicating roughly 30% of its max output—a sanity-preservation cap imposed by Oklahoma's 63-year-old coach, Lon Kruger, whose office is above the practice court. But with the coaches gone for the night, Hield has cranked it up to 85%, a level that drowns out the bounce of the ball and the snap of the net on his backspin-heavy swishes. The music blares out of speakers hung from the rafters and makes the floorboards vibrate to the touch. "It hits you in your soul," Hield said of dancehall earlier in the day, when it was possible to converse about optimal shooting soundtracks. "And you've gotta blast it. If you play it low, you don't get the vibe. You've gotta feel the beat thumping."

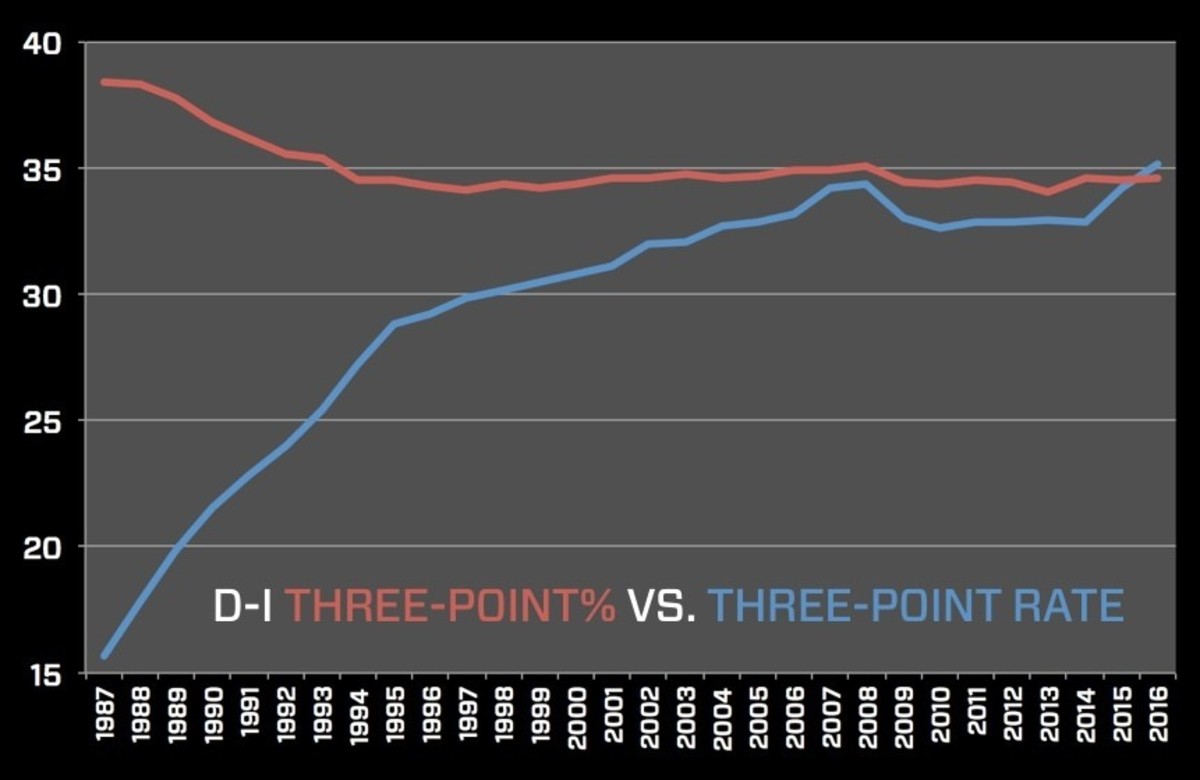

There is no college shooter more in rhythm than the 6' 4" Hield, who has made a remarkable 50.0% of his 8.3 long-range attempts per game for a team that's ranked No. 3 in the polls, No. 1 nationally in three-point accuracy and No. 1 in the Big 12 in three-point rate (meaning the highest share of their shot attempts are threes). In this, the season with the highest three-point rate in the 29-plus years college basketball has used the arc—treys account for 35.2% of all Division I shot attempts—it's appropriate that the front-runner for national player of the year is also the game's most dangerous, indefatigable and joyful distance shooter.

The sounds take Hield back to the Bahamas and the "crate courts" he made as a kid by nailing a milk crate, with its bottom removed, to the shed in his grandmother's backyard. Hield would get scolded for trampling her flowers and her okra, and if he wanted to take a long shot, he had to avoid the hanging branches of a kenep tree. Now that Hield has around-the-clock access to obstruction-free rims, he doesn't take it for granted. On this day he did a morning shooting workout, an afternoon practice with the team and is back to shoot again at 6:37 p.m. He goes through an epic sequence of shots—the majority of them threes—on three different hoops, taking breaks at random intervals to do one of four things: Refuel by swigging from a 16-ounce can of Monster Energy and eating from a bag of gummy bears (six separate times), dance to choice tracks, change the mixtape once it gets stale or study ESPN college hoops footage—including a montage of highlights of himself—that plays on the gym's wall-inset TV. At 8:24 a visitor asks Hield (by shouting over the music) how much longer he plans to shoot. "Until I feel comfortable!" he shouts back.

It takes hundreds more shots for Hield to find the right vibe. Finally, at 9:23, after a satisfactory run of swishes, he calls it quits and finishes his gummy bears. He'll shoot again the next morning at 10, and there will be another team shootaround before the Sooners depart for LSU, where he'll go 8 of 15 from deep (and score 32 points) in a 77–75 victory. It's yet another net-ripper in the Winter of Buddy Love, a season in which college basketball has collectively jacked up its three-point volume.

*****

Joe Robbins/Getty

All shooters in this era must bow to Stephen Curry, for he is the god and the revolution. The NBA's reigning MVP is on pace to obliterate the league's single-season records for three-point makes and attempts. Curry's Warriors and the analytically savvy Rockets are the radicals pushing the NBA to new heights of three-point reliance; in 2014–15 the Rockets set the standard for three-point attempts, and Houston, Charlotte and Golden State lead the NBA this season in three-point rate, taking 37.9%, 34.8% and 34.8% of their shots as threes, respectively.

While several college coaches postulate that D-I's rising reliance on the three is due to a "Curry Effect"—a natural desire to mimic the greatest show on hardwood—it is worth a reminder that college is the true home for long-range extremism. NBA teams' three-point rate is 28.2%, compared with college's 35.2%. What's more, at week's end 106 of the 351 D-I teams had a higher three-point rate than do the pioneering Rockets or Warriors. One of those teams is Hield's Sooners. Another is Curry's alma mater, Davidson. The Wildcats took 39.2% of their shots as threes during Curry's breakout sophomore campaign of 2007–08 but have ramped that up to 45.6% and 45.1% over the past two seasons. It was not that Curry was restricted as a collegian; his coach, Bob McKillop, grants players "licenses" to shoot, and says that "Steph had a truck license from the day he walked in." As a sophomore Curry set the NCAA single-season record for threes, with 162, and when Davidson's almost-completed practice facility needed to be christened last September, a visiting Curry took the first shot, banking in a three from 30-plus feet while wearing a hard hat. It's just that Davidson now has two three-point-gunning guards, Jack Gibbs and Brian Sullivan, and uses lineups with four players licensed to take threes.

And while the NBA has three-point specialists, such as Kyle Korver, who takes 64.7%of his shots from deep this season, college has a three-point unicorn.Max Hooper, a 6'6" senior at Oakland, had attempted 195 field goals this season and every one of them was a three. Sports-Reference.com college data going back to 1994–95 indicates that Hooper is the only 100% threes shooter of any notable volume; the closest anyone else has come to that level was Central Michigan's Josh Kozinski, who took 98.0% of his shots from deep last season. In 2013–14, Hooper was losing his mind while languishing on the bench at St. John's, and his "therapy" was to rip off 500-plus-shot sessions while a shooting gun tracked his accuracy. He transferred to the Rochester, Mich., campus, where coach Greg Kampe recognized Hooper's immense value as a catch-and-shooter running off screens. (He has made 45.6% of his attempts this season.) Hooper knows his role is unique, but says, "It's not a circus act. I think my coaches believe, and I believe, that I'm the best shooter in the country."

The few high-volume marksmen who can contest that claim are Hield, Michigan State shooting guard Bryn Forbes (a 50.3% shooter) and Michigan forward Duncan Robinson (48.0%), whose recruitment was an outside-the-box move by a team that puts a premium on long-range offense. Two seasons ago the 6'8" Robinson was a superefficient scorer at Division III Williams. A D-III player transferring, on scholarship, to a high-major D-I happens as often as NBA teams sign players straight out of, say, the Philippines' pro league: never. But Robinson's AAU and high school coaches put out feelers to a few perimeter-oriented D-I teams on his behalf, including Michigan, Davidson and Creighton, and Wolverines coach John Beilein, who'd just lost 44.1% three-point shooter Nik Stauskas to the NBA draft, was intrigued.

"We needed somebody who was a proven shooter," says Beilein, who requires his players to meet a minimum standard to get green-lit for games: making 60 threes in a five-minute, one-ball, one-rebounder drill that's an adaptation of a workout Bryce Drew did as a Valparaiso guard. Stauskas, who's now with the 76ers, held the unofficial Michigan record with 78 in five minutes ... until Robinson, on Dec. 2, 2014, during his redshirt season, broke it by making 83 of 89. Robinson has been the fourth-most efficient scorer in the country, and the Wolverines have the highest three-point rate (46.1%) of any major-conference team. When Beilein took Michigan to the national-title game in '13, its three-point rate was a significantly lower 34.2%.

*****

Joe Robbins/Getty

That brings us to an ominous question for the NCAA's three-point extremists. Can one of these teams actually win a title, in a championship format that requires six consecutive victories, on three neutral courts? It has only happened once, and that was 15 seasons ago, when 2000–01 Duke had a three-point rate of 41.8%—but that was a juggernaut with five future NBA players in its rotation. The average three-point rate for title teams over the past decade is 31.2%—lower than the 33.4% rate for all teams during that span. While there have been 380 college teams over the past decade with three-point rates higher than 40%, only one of them, '10–11 VCU, reached the Final Four, and that was as a wildly improbable 11th seed.

A few Hall of Famers have yet to embrace the revolution. John Calipari's 2011–12 Kentucky team had the lowest three-point rate (26.5%) of any title winner in the past 10 seasons, and his 2014–15 juggernaut had a similar profile (27.1%). Roy Williams's 2008–09 North Carolina team had a three-point rate of just 23.2%, and his current, No. 9–ranked Tar Heels have taken 26.6% of their shots from deep, the 15th-lowest rate in the nation. "The No. 1 thing you have to have is balance," Williams says. "The biggest reason I don't ever want to be the one shooting 25 threes per game is you never get the other team in foul trouble. When the other team's best players are on the bench at the end of the game, you have an advantage." The Tar Heels' most frequent three-point shooter over the past two seasons, senior guard Marcus Paige, says he's ever-conscious that "the three takes a backseat to getting transition baskets and throwing the ball inside." Assistant coach Hubert Davis even encouraged Paige to set a goal that he take fewer than 50% of his attempts from deep, though Paige isn't there quite yet (55.3%).

Top-ranked Villanova, on the other hand, operates under a starkly different philosophy: that its players should always be hunting in-rhythm threes. Coach Jay Wright says that in 2013, a study written by then-assistant Billy Lange (who's now with the 76ers) swayed Wright on the "value of three-point attempts"—that focusing on limiting opponents' volume and increasing Villanova's volume was more important than focusing on three-point percentage. Over the next three seasons ('13–14 to the present) the Wildcats have ranked seventh, 22nd and 16th nationally in three-point rate, taking an average of 44.2% of their shots from deep. This has corresponded with a career-best run of success for Wright—an 83–11 record, a No. 1 and a No. 2 seed in the NCAA tournament—but Villanova has also been upset on the first weekend of both Big Dances. While Wright is aware of the volatility of three-point reliance, he didn't take either loss as an indictment of his strategy. "If you don't have personnel and length like a Kentucky, your best way of getting to the Final Four is by using the three," he says. "If you try to follow a Kentucky formula and you don't have that personnel, you'll get killed."

*****

Luke Winn/SI

Kruger's first deep NCAA tournament run as a coach came in 1987–88, when he took Kansas State to the Elite Eight. It was the second season of the NCAA's three-point era, and the Wildcats had a phenomenal shooting trio in Steve Henson, William Scott and future NBA gunner Mitch Richmond, who combined to make 49.1% of their treys. But threes accounted for just 21.0% of the Wildcats' attempts, and the national three-point rate that season was just 17.8%. "When the line first came in, coaches in general were cautious," Kruger says. "No one was sure how many threes were appropriate to take."

With his current Sooners, Kruger has another elite cast of shooters—Hield, senior point guard Isaiah Cousins, junior two guard Jordan Woodard and senior power forward Ryan Spangler have combined to make 47.0% of their treys—but he has made a far bigger commitment to perimeter offense. Oklahoma's three-point rate in Big 12 games is 43.0%, and as Kruger puts it, "Shooting the three is at the core of what we do."

What's most intriguing about this Sooners crew—aside from the way Hield and Cousins (who's from Mount Vernon, N.Y., but has Jamaican relatives) fire away to dancehall-reggae—is that none of them were three-point threats when they arrived. All have undergone multiyear overhauls under the guidance of Kruger and assistants Henson, Chris Crutchfield and Lew Hill in what should be known as the Norman Shooting Laboratory. Cousins was a 25.0% long-range shooter as a freshman, before he had a complete mechanical makeover that changed him from a herky-jerky, overhead slinger into a fluid marksman (46.8%). After Woodard removed a hitch in his form this off-season, he was shifted from the point to put him in more natural shooting positions. He has jumped from 25.4% accuracy as a sophomore to 48.6% this year. When Crutchfield first saw Hield as a teen at a showcase in the Bahamas, he was shooting from the hip, and though he had raised his starting point by the time he arrived in Oklahoma, his form was all over the place. "I had a good follow-through, but my shot was on the wrong side of my head," Hield says. Now he starts his righthanded delivery with the ball just above his right eye, and his entire form is so perfectly square and repeatable that you could overlay footage of him taking 20 threes and it would look like one attempt.

Hield's stroke had become so consistent by his sophomore year that Henson decided to test him. He had read that Curry and Klay Thompson's favorite drill with Golden State was to roam the NBA arc and see how many threes they could make before they missed two in a row; in a 2013 story, SI wrote Curry's high score was 76 and Thompson's was 122. "One day after shootaround I said to Buddy, 'Hey, let's just do this for fun, see how many college threes you can make without missing two in a row.' He got to 142. And it wasn't like make two, miss one, make three, miss one. It was make 20, miss one, make 25, miss one. He just pours it in."

Hield and the rest of the Sooners have poured it in on everyone this season, but can they defy the data that show heavily three-point reliant teams rarely, if ever, win a national title? They have unprecedented long-range accuracy, a multitude of options and no fear of history. "If you're telling me it can't be done," Kruger says, "we're not going to change. This team was made to shoot the three." And this could be the team that truly shoots its way to a championship. Pick against Buddy Love, whose shot, honed in his high-decibel club, has unshakable rhythm, and you're liable to hear what he tells late-closing defenders just after the ball leaves his hand: You messed up.