Fate of the Union: How Northwestern football union nearly came to be

This story appears in the February 29, 2016, issue of Sports Illustrated. Subscribe to the magazine here.

Adapted from Indentured: The Inside Story of the Rebellion Against the NCAA by Joe Nocera and Ben Strauss. Used by permission of Portfolio, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. © 2016 by Joe Nocera and Ben Strauss. All rights reserved. Order your copy on Amazon.

On a below-zero morning in January 2014, Ramogi Huma and Tim Waters walked into the National Labor Relations Board office on West Adams Street in downtown Chicago. Huma, a former UCLA linebacker and a lifelong resident of Southern California, had bought his first winter coat before making the trip, but he barely noticed the cold. He was carrying a package that represented something he and Waters, the director of the United Steelworkers Political Action Committee, had been thinking about for the last year. It contained union cards signed by almost all of the football players at a Big Ten university.

“We’re here to unionize the Northwestern football team,” said Huma, the founder and president of the National College Players Association (NCPA), which puts public pressure on the NCAA to expand the rights and benefits of athletes. The NLRB clerk did a double take.

Fifteen miles away, on Northwestern’s campus in Evanston, Kain Colter sat in a meeting with his coach, Pat Fitzgerald. Colter, then 21, had been Northwestern’s starting quarterback for the past two seasons. He was a team captain and in 2013 had piloted the Wildcats to a Gator Bowl victory, Northwestern’s first bowl win in 64 years. Fitzgerald, for his part, was an icon on campus, a former All-America linebacker who had led the 1995 Northwestern team to the Rose Bowl.

Colter told his coach that he believed it was important to change college sports, that the power structure marginalized players and that he had deep concerns about issues such as long-term health care for college athletes. The team had signed union cards, he said, which were being filed as they spoke. Fitzgerald said, “I’m proud of you guys for doing this. I think it’s a great cause, and you’re bringing up great points.” But, according to Colter, the coach also said that before he could take a public position, he had to see how the school wanted to handle it. (Fitzgerald denies saying this.)

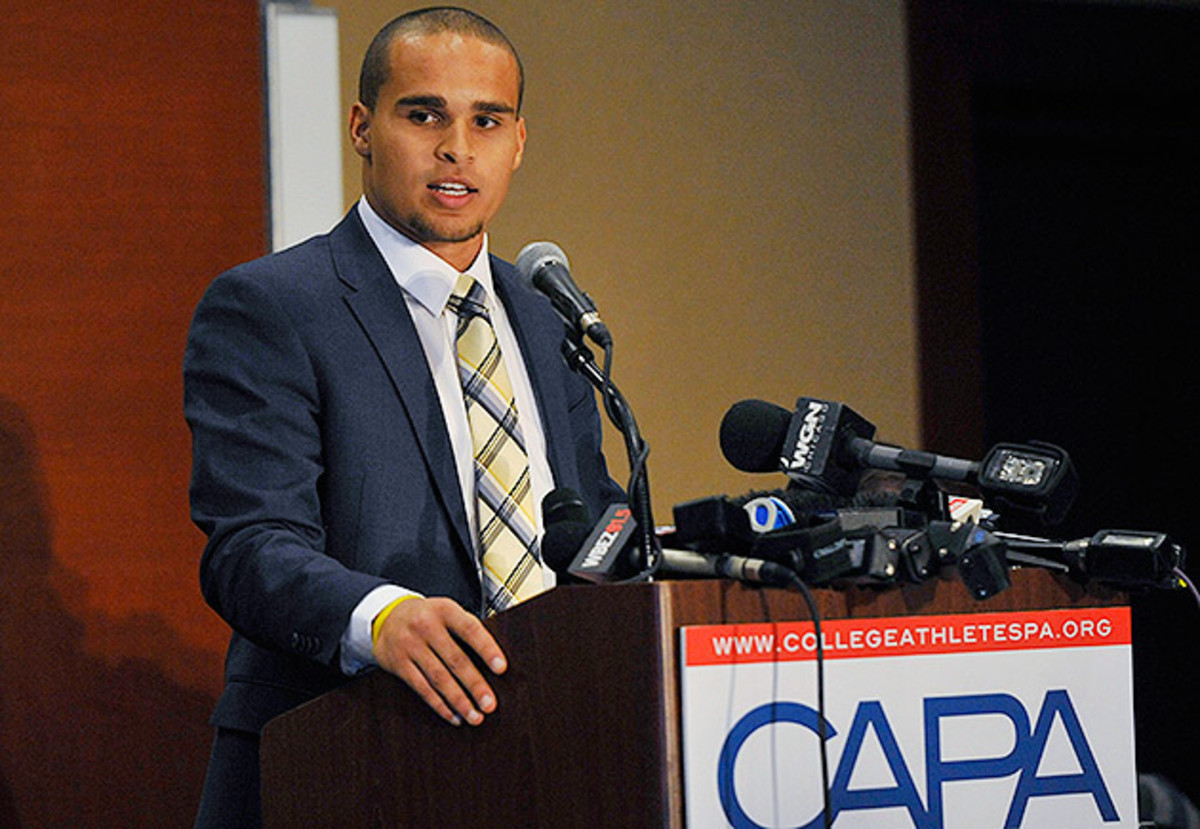

Later that morning Huma and Colter held a press conference at the Hyatt Regency in downtown Chicago. Northwestern players sought employee status under the law, they said, and with it the ability to bargain collectively through a new entity that Huma and Colter had formed the same day: the College Athletes Players Association (CAPA). In front of TV cameras and a room full of reporters, Colter said, “The current model resembles a dictatorship, where the NCAA places these rules and regulations on these students without their input or without their negotiation.”

Colter continued, “The NFL has the NFLPA, the NBA has the NBAPA, and now college athletes have the College Athletes Players Association.”

***

When Ramogi Huma was a freshman at UCLA, in 1995, one of his teammates, All-America linebacker Donnie Edwards, told a local radio station that he didn’t have enough money to buy food. A few days later an agent left a bag of groceries worth about $150 on Edwards’s doorstep. When the NCAA found out, Edwards, who would go on to have a long and successful pro career, was suspended for one game. The suspension had a profound impact on Huma: UCLA could sell Edwards’s jersey in the campus bookstore for $50, but he couldn’t afford dinner?

The summer after Huma’s freshman year, his coaches recommended that he participate in summer workouts with the team but also told him that because the workouts were voluntary and didn’t occur during the school year, NCAA rules prohibited UCLA from providing health insurance. Huma was stunned. “It was very clear that something wasn’t right,” he says.

Unlike most college athletes, Huma didn’t just let that thought pass. As a sophomore he founded the Collegiate Athletes Coalition, which in the mid-2000s would become the NCPA. Over the next decade Huma built an organization with members at more than 150 schools. He even persuaded the United Steelworkers to join his cause, leading The Wall Street Journal to christen him the “Norma Rae of jocks.”

Huma’s future partner in the Northwestern unionization drive, Colter, grew up in Boulder, Colo., with sports in his blood. His uncle Cleveland Colter was an All-America safety at Southern Cal in 1988. Kain’s dad, Spencer, was a safety on Colorado’s ’90 national championship team and went on to coach high school football.

At 6'1", Kain was undersized for a quarterback, but he had quickness and smarts. As a junior he was recruited by Texas Christian, Northwestern and Stanford, among other schools. He committed to Stanford. “That was my dream school,” he says. “I loved the academics, loved Palo Alto.”

But early in his senior season Kain suffered a torn labrum while reaching for a fumble. He tried to play through the pain, but his performance suffered. The letters and phone calls from Stanford’s coaches slowed to a trickle, and eventually the school told him he wouldn’t be accepted. Crushed, he frantically looked for another scholarship. Northwestern was still in the market for a quarterback, so Kain headed east to the Big Ten.

Colter spent his freshman season on the bench, redshirting. Then, late in the year, starting quarterback Dan Persa ruptured his Achilles tendon. Fitzgerald asked if Colter would step in and play—in other words, sacrifice a full year of eligibility for the three remaining games. Colter agreed, and on Jan. 1, 2011, he had his breakout moment in the TicketCity Bowl, rushing for two touchdowns in a 45–38 loss to Texas Tech.

• Culture Clash: Title IX suit shines light on problems at Tennessee

Colter had arrived in Evanston with two dreams: to be an NFL quarterback and, after his playing days, a doctor. He began on a premed track, but as a quarterback on scholarship he needed to be at every minute of practice, and team activities conflicted with the science classes he needed. He fell behind and pushed the classes to the summer before finally switching his major to psychology. “I had a chance to be a pro football player or a doctor,” he says, “but I couldn't do both.”

There were other aspects of college football life that bothered Colter. Stipend checks for off-campus living, which were part of his scholarship, were difficult to stretch, especially because the team mandated that players buy meals from the athletic department. He spoke to friends and former high school teammates at other schools who were also struggling financially. Many of them, unlike Colter at Northwestern, were also concerned about the lack of academic support they received.

Colter’s biggest concern, however, was medical care. Northwestern and other athletic departments provided a health policy for players—but usually it was only a supplement to a player’s primary insurance, provided by his or her parents. If the parents couldn’t afford it, the athlete might have to pay out of pocket for the school’s health plan. Once players left school, they also had few guarantees of health coverage for injuries they had sustained on the field.

Colter’s uncle Cleveland had been considered a shoo-in to jump to the NFL from USC—until he suffered a severe knee injury. He never fully recovered. Not only was Cleveland not drafted, but he also didn’t graduate. Now he runs a catering business, and his knee still bothers him. “Think about a 20-year-old kid who’s got all this pressure from his family—he’s getting ready to be drafted in the first round, and he tears his knee up,” Kain says. “You’re thinking, I’ve been working my whole life for one thing, and now it’s out the window.”

In the summer of 2013, Colter took a seminar called Field Studies in the Modern Workplace. A field trip to a Chicago steel mill sparked a discussion about why blue-collar workers had unionized. One rationale was health and safety protection. Colter offered a parallel to college football players. “In the NFL, the NBA and baseball, the unions help protect the players,” he said. “And without them, players wouldn’t be treated fairly.”

Around the same time, Colter met Tregg Duerson, a graduate of Northwestern's business school whose father, Dave, had played 11 years in the NFL. Dave Duerson killed himself in 2011, at age 50, with a gunshot to the chest. He was later found to have chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), presumably caused by repeated hits to the head. Tregg helped Colter understand the dangers of football well beyond his uncle's story.

Colter wrote a paper for his seminar describing the NCAA as a cartel and raising the possibility of a union. He also searched the Internet—"Can college players have a union?"—and found Huma's NCPA. In the comments box Colter shared his frustrations and ideas. He hit send. "I really didn't think I was going to hear back," he says.

***

When the Steelworkers agreed to back Huma in 2001, unionization was a step that he and Waters were reluctant to take. Huma continued to complain that athletic scholarships did not cover the full cost of attending college and that players saw next to none of the spoils of a college sports industry that generated billions of dollars. In 2012 he worked on a study with Drexel professor Ellen Staurowsky that found the average scholarship fell short of what top-division football players needed by more than $3,000 a year, while more than 80% of athletes playing football on “full scholarship” lived below the poverty line. What’s more, the study found that if revenues were shared among players and owners as in pro sports, each Division I football player would be worth $137,357 per year.

Huma also helped end the NCAA's ban on multiyear scholarships by speaking to the Justice Department. Not long after Justice officials questioned the NCAA about the policy, schools were given the option of offering four-year scholarships that were not contingent on a coach’s approval after each season.

But even Huma’s successes could be bittersweet. In the fall of 2012, California governor Jerry Brown signed a law called the Student Athlete Bill of Rights, which provided new scholarship and health protections for players in the state’s biggest college sports programs, including mandated health coverage for two years beyond eligibility. But it had passed the legislature only after it was stripped of other important provisions, such as one allowing players to transfer and compete for their new school right away.

“We wanted the NCAA to listen, to come to the table with us,” Huma says. But the NCAA did neither, and by the time Colter came calling, Huma was ready for bigger and bolder action, due to new publicity about an old problem: concussions.

In April 2010 the NCAA held its first-ever concussion summit, during which it released a survey of athletic trainers. The results were troubling. Less than 50% of schools required a physician to see all athletes who suffered concussions; 39% had no guidelines on how long athletes should sit out before returning to play; nearly half said they allowed athletes to return to play in the same game in which they suffered a concussion. Finally the NCAA was moved to act—barely. It mandated that universities develop their own concussion protocols, but it did nothing to monitor them. Was anyone ever disciplined for not following safety rules? “Not to my knowledge,” David Klossner, the NCAA’s director of health and safety, later said.

The importance of stronger safety protocols only became clearer in the ensuing months. Owen Thomas, a junior lineman at Penn, hanged himself in his off-campus apartment that same April. Five months later doctors examined his brain and found evidence of early stages of CTE. In 2011, Adrian Arrington, a former safety at Eastern Illinois, sued the NCAA over its lack of concussion policies. Arrington had sustained five concussions during his career, some severe enough that he didn’t immediately recognize his parents afterward. By the time he was 27, Arrington was on welfare and couldn’t hold a job because of seizures so violent that during one, he tore his rotator cuff. (In December ’13 the NCAA would make a jaw-dropping legal argument in filings on a wrongful-death suit brought by the family of Derek Sheely, a former Division III football player at Frostburg [Md.] State. Sheely collapsed after repeated blows to the head during a preseason drill in ’11. He died six days later. “The NCAA denies that it has a legal duty to protect student-athletes,” the filing read.)

Huma, desperate for a way to bring attention to college football’s concussion crisis, traveled to Miami Gardens, Fla., for the Jan. 7, 2013, BCS championship game between Alabama and Notre Dame. Along with Morgan Thomas, Owen’s brother, he attempted to call a press conference at the media hotel, but hotel staff wouldn’t allow it—college football officials didn’t want him there. “It was a breaking point,” Huma says. “When we couldn’t talk about concussions, we had to change course.”

Later that year Huma finally met with the NCAA’s new chief medical officer, Brian Hainline, to talk about concussions and player safety. Hainline said that he alone couldn’t impose new safety regulations; they had to come from the membership.

***

Huma called Colter within an hour of receiving the player’s email. The first words out of Colter’s mouth were, “College athletes need a union.” Union was a word Huma had been avoiding for nearly 15 years. For starters, his backer on the Steelworkers, Waters, was opposed to it, not least because of the huge undertaking it would entail, from hiring lawyers to organizing to finding the right player to lead the charge. Waters had also never thought unionizing would be necessary. “College sports, to me, was an issue of, Lift up the rock and see what’s underneath,” he says. “Once people saw what was really going on, it wasn’t going to take a union to change it.” But the rock was up, and nothing had happened.

Colter’s arrival before the 2013 season helped change the dynamics at the NCPA, which had long been a one-man operation. Now Huma had a fellow football player as a copilot. Colter, a three-time member of the Big Ten’s All-Academic team, was articulate, persuasive and full of energy. As Waters says, “Kain was like the second coming of Ramogi.”

The quarterback joined a conference call Huma had arranged a few times a month with a handful of other players around the country. Colter heard them talk about the same things he noticed: too-small stipend checks, lack of medical coverage, watching teammates and friends fail to graduate. He soon recruited a Northwestern teammate to participate in the calls and pressed Huma and Waters to begin moving on a union. “He wanted everything to be bigger, to be more public,” Waters says. "He always wanted to know what was next."

That fall Huma and the athletes on the conference calls devised a way to publicize their concerns: Players would write apu, for All Players United, on their wrist tape during games one Saturday in a show of solidarity. Colter and several Northwestern teammates displayed the acronym. So did Georgia Tech quarterback Vad Lee and several Georgia offensive linemen. Waters watched Northwestern play Maine that afternoon in a game televised by the Big Ten Network. When the camera focused on Colter, Waters took a photo with his phone, then zoomed in on the APU. He tweeted the image with the caption, “Northwestern Star QB (Colter) wears #APU logo on both wrists to join @NCPANOW national player solidarity action today.”

Northwestern Star QB Coulter wears #APU logo on both wrists to join @NCPANOW national player solidarity action today pic.twitter.com/fSz4imJgrE

— Pol Dir Tim Waters (@USWPolitical) September 21, 2013

The response to the APU protest was predictable. Fitzgerald told Colter that it should have been discussed within the team beforehand. But Colter says that when he asked if he could address the team about the APU movement, the coach said no. (Fitzgerald says Colter never asked.)

Later that fall Waters had come around; he quietly floated a college players’ union to Steelworkers leaders and other top labor minds. Colter was changing the NCPA. “You have to be born with this, to be a leader,” Waters says. “Here he was, the real deal. This wasn’t a third-string safety; this was a quarterback of a Big Ten team.”

Waters and Huma flew to Evanston later that fall, and Waters gave Colter a crash course on organized labor. As a private university, Northwestern was governed not by state law but by the National Labor Relations Board. Thirty percent of the team had to sign cards to allow a vote on unionization to go forward, and then, after Northwestern refused to recognize the validity of such a vote—a near certainty—there would be a public hearing before the regional NLRB. The Steelworkers would handle legal questions. They would look into who was eligible and what an employee designation would mean for players. Colter, meanwhile, would organize the team.

Colter had to spread the word among his teammates slowly, without alerting the coaches. Some players had questions about employee status—would they be able to play against other teams of nonemployees? But most had many of the same gripes Colter did and agreed that, coming from a Big Ten school, they were in a unique position to put pressure on the NCAA. “Nobody said, ‘This is crazy. Screw you,’” Colter says.

• McCANN: Legal analysis of new developments in Tennessee case

Huma and Colter organized a series of conference calls with the handful of players who were the most enthusiastic about organizing. The union cards, they decided, would wait until after the football season. To present the cards to the team, Colter reserved a classroom for Sunday, Jan. 26. Northwestern players received texts about an “urgent players-only meeting,” and they arrived in groups of 20 throughout the afternoon.

Colter addressed each group, explaining how he had gotten involved in the players’ rights movement. He stressed the gravity of the moment. This would be covered by ESPN and CNN, he said. He then introduced Huma, who talked about the NCPA, the Steelworkers’ involvement and the cost-of-attendance issue while promising that the union would not affect other sports on campus. He had a packet of FAQs and their answers for each player. Huma guaranteed total confidentiality for everyone who participated.

Colter finished the pitch with a personal story. He played much of his senior season on injured ankle cartilage, and as he trained that winter for the NFL draft, the injury continued to bother him. But when he asked the school to pay for an MRI, it declined. He paid for it himself and found he needed ankle surgery. Only then did Northwestern offer to reimburse him and find a doctor to operate. (Northwestern says Colter failed to properly notify the school about the MRI, and once the needed paperwork was filed, the school was willing to pay for the procedure.)

Players had plenty of questions. Would they have to pay union dues? Huma assured them they would not. Others asked about their popular coach. Colter said he would talk to Fitzgerald. Each group was given union cards. Almost every player signed. The organizers looked at one another, wide-eyed. “We knew we made history,” Colter says.

***

Two days later Huma turned in the cards. It was national news, just as Colter had predicted. And while not every commentator approved of the idea of a college athletes’ union, Colter drew praise for raising the issues of health care and NCAA intransigence. Northwestern athletic director Jim Phillips denounced collective bargaining but said, “We love and are proud of our students. Northwestern teaches them to be leaders and independent thinkers who will make a positive impact.... Today’s action demonstrates that they are doing so.” Fitzgerald tweeted, “Kain and our student-athletes have followed their beliefs with great passion and courage. I’m incredibly proud of our young men! GO CATS!”

Kain and our student-athletes have followed their beliefs with great passion and courage. I'm incredibly proud of our young men! GO CATS!

— Pat Fitzgerald (@coachfitz51) January 28, 2014

Not surprisingly, Northwestern refused to recognize the players as employees, so a hearing before the regional NLRB in Chicago was scheduled for February. An employee, under the National Labor Relations Act as well as Supreme Court precedent, is an individual who performs services for another, under the control of another, for compensation or payment. The NLRB had dealt with a similar case in 2004, when it ruled that Brown University graduate teaching assistants were not employees because they were primarily students. The Steelworkers were unconcerned with that precedent, however. There was little reason, Waters thought, that the players could not be both students and employees.

The Steelworkers had spent months preparing arguments and lined up some legal heavyweights. John Adam had argued more than a hundred cases before the labor board. His hearing partner was Gary Kohlman, a D.C. labor lawyer and a pit bull of a cross-examiner. The gist of CAPA’s case was simple: The players were already employees because they were paid with a scholarship that the school valued as high as $76,000. In exchange, the players were expected to put in huge amounts of work with the football team under the strict control of their coaches, who were effectively their bosses. And if they did not follow the rules, they could lose their scholarships.

Colter, who was completing his final two courses while rehabbing his injured ankle and training for the draft in Bradenton, Fla., flew in to testify first. He said he sometimes spent 50 or 60 hours a week with the team, and he needed the team’s approval to do mundane things such as move out of the dorm into an off-campus apartment.

Adam walked Colter through the itinerary for the Wildcats’ Nov. 10, 2012, game at Michigan. With more than 10 hours of travel, a four-hour football game and hours more of meetings and team meals, the trip required nearly 24 hours with the team, which seemed to exceed NCAA’s limit on sports participation to 20 hours each week. But the NCAA, it turned out, had a loophole in this arithmetic: Time related to a game event—travel, play, team meetings and everything else—counted for only three hours against the cap.

When announcing the union, Colter had tried to be clear that his beef was primarily with the NCAA, not with Northwestern. But only by taking on Northwestern could he take on the NCAA, which created a more ambiguous situation. Northwestern lawyer Anna Wermuth noted that Fitzgerald had created a Leadership Council to give players some voice in team rules. Colter countered by saying that Fitzgerald retained 51% of the power. “We get an input,” Colter said, “but at the end of the day he’s the boss man."

Wermuth also brought up Colter’s ankle to illustrate how Northwestern took care of players after graduation. “So they did say they would reimburse you for the MRI?” Wermuth asked.

“After they denied me,” Colter interjected. “But I mean there shouldn’t be any gray area. I gave—I sacrificed my body for four years. They sold my jersey in the stores, and they should protect me as far as medical coverage.”

A columnist for the Chicago Sun-Times described Colter as “slinging mud” and “belligerently grandstanding.” Alumni and former teammates wanted to know why he was killing the program. An assistant coach told Colter he couldn’t believe the quarterback had referred to Fitzgerald as boss man. The criticism, Colter said, was fierce: You don’t deserve to get paid; you signed up for this, you piece of crap. “I felt like I had burned all these bridges with Northwestern,” he says, “after I dedicated so much of my life there.”

Colter’s testimony changed the way some current players viewed the union push. Some questioned why he had publicly thrown Fitzgerald under the bus. Some felt that Colter, focused on the NFL, had less invested in Northwestern than they did. They were left to fight his battle, and they didn’t like seeing their school under fire.

Underlying some of the criticism of Colter was the belief by the school and many of its alumni that Northwestern was the wrong place to highlight the pitfalls of college sports. In many ways that was true. It had a graduation rate of 97%, the highest in college football’s top division, and a history of providing some medical coverage even after an athlete’s playing days had ended. As soon as the NCAA allowed schools to guarantee four-year scholarships, Northwestern was one of the few to do so immediately. In truth, the university treated its players about as well as any school did—and as well as NCAA rules allowed. This was part of Northwestern’s defense. Colter’s concerns were NCAA issues, the school’s lawyers argued. Northwestern couldn't distribute cost-of-attendance stipends, for example, without the association’s approval.

Northwestern called other players to testify, and each presented compelling evidence that the university valued schoolwork. But none refuted Colter’s accounting of the hours or the coaches’ control. Then came Fitzgerald. “We take great pride in developing our young men to be the best they possibly can be in everything that they choose to do—athletically, academically, socially,” he said. But Kohlman got him to concede that the players can spend 24 hours on football on a Friday and Saturday when they travel to away games. He acknowledged that he set team rules too. In an interview the year before, Fitzgerald had called being a student-athlete “a full-time job.”

“We won the case with Fitzgerald on the stand,” Kohlman says.

***

A month later, Peter Sung Ohr’s decision rattled college sports. The NLRB regional director eviscerated the NCAA's bedrock principle that college athletes were first and foremost students. “The players spend 50 to 60 hours per week on their football duties during a one-month training camp prior to the start of the academic year and an additional 40 to 50 hours per week on those duties during the three- or four-month football season,” the ruling said. “Not only is this more hours than many undisputed full-time employees work at their jobs, it is also many more hours than the players spend on their studies.” Ohr also noted that Northwestern football reported $235 million in revenue from 2003 to ’12.

“Is this real? Did we really win?” Colter shouted when Huma phoned him with the news.

“Then things really got crazy,” Colter says.

Panic swept athletic departments. Sports officials outdid each other with doomsday scenarios. NCAA president Mark Emmert called a union “grossly inappropriate.” Former Northwestern president Henry Bienen proclaimed that the university might leave Division I. “What happens if school A or school B becomes a union school?” Big Ten commissioner Jim Delany asked Chicago Sun-Times columnist Rick Telander. “You don’t know. I have no idea! Places where there are unions, places with no unions, no NCAA, no NCAA rules? I think you would have chaos.”

• BAUMGAERTNER: What did each Big Ten team learn from 2015 season?

Northwestern immediately appealed Ohr’s decision to the full NLRB in Washington, and a group of congressional Republicans submitted a supporting amicus brief. A U.S. House of Representatives committee called a hearing in May that brought Stanford athletic director Bernard Muir and Baylor president Kenneth Starr (yes, the former Bill Clinton antagonist) to D.C. to lament the unionization drive. If Stanford players unionized, Muir said, the school would look for a new way to run its sports programs.

The Northwestern football team wasn’t even unionized yet. An election was scheduled for April. Seventy-six players were eligible to vote, and the union had to be certified by a majority of the ballots cast. Northwestern, like any employer fighting a union drive, set out to beat the vote.

Fitzgerald announced that he had told the players to vote down the union. “I just do not believe we need a third party between our players and our coaches, staff and administrators,” he said at a spring practice. This became the theme of the school’s campaign—one that heaped immense pressure on the shoulders of 18- to 22-year-olds. When the players returned to practice after Ohr’s ruling, they were given new iPads and a trip to a bowling alley. (Northwestern counters that the iPads were ordered in December 2013, and that the team organized regular outings, including several to Chicago Blackhawks games.) Position coaches talked to players. Parents were emailed.

The team solicited anonymous questions from players, parents and staff and compiled a 21-page Q&A. The message was that a union could result in fewer benefits. Players were allowed, for instance, to travel home for emergencies, but that privilege could become contingent on collective bargaining.

To be sure, there were pitfalls to the union approach. A national union representing college athletes was far-fetched, given the different labor laws in each state and the fact that college teams included both private and public institutions. The impact on Title IX and what an employee model meant for workers’ compensation, unemployment benefits and potential salaries were unclear as well.

There were also things a school could do within the constraints of the NCAA, whether the players unionized or not. Northwestern could cut the number of full-contact practices it held, and it could guarantee long-term health care to injured players. If Northwestern’s football players could bargain for those things—benefits that didn’t violate NCAA rules—then, the theory went, other schools would follow suit to keep up in recruiting.

These questions, though, were mostly pushed aside as the school threw its weight behind defeating the union push. Dan Persa, the former Wildcats quarterback, warned players that Fitzgerald might leave if they voted for the union. Players heard other ominous warnings—that donations could dry up, or a new $225 million athletic center could be scrapped. Players got calls from alums telling them that casting their lot with Colter could hurt their job prospects after graduation; the Northwestern alumni network would desert them.

Colter, meanwhile, held his pro day at Northwestern to work out for NFL scouts in early April, only to find that some of his former coaches wouldn’t speak to him. (A Northwestern spokesman replied that the school arranged the workout specially for Colter, because he had been injured.) As Colter was vilified, however, certain alumni grew concerned that the university was turning its back on its former star quarterback and that the players were being bullied into voting down the union. Led by Kevin Brown and Alex Moyer, who both played for Northwestern in the 1980s, a small group went to see Fitzgerald. According to Brown, Fitzgerald was also concerned about the pressure on the players. “Players were torn because they didn’t want to disappoint their coach,” Brown says. "[But] a coach represents the university’s interests more than the players’ interests. We didn’t care one way or the other if they formed a union, but they should be allowed the freedom to exert their rights.”

Brown and Moyer called a meeting at a community center in Evanston the week before the vote to voice their concerns. Around 60 former players, going back to teams from the 1970s, were there, as well as a handful of current players. “I’m worried Kain is becoming a pariah,” Moyer said to the group.

“He chose to be a pariah,” jeered an alum.

As the vote neared, Colter and Huma returned to Evanston and called a meeting of players at a hotel near campus. Some players didn’t like the way their new iPads had been portrayed as bribes; they also wanted to know why other schools hadn’t followed their lead. Colter and Huma had said they were talking to players at other, unnamed universities, but Northwestern was alone in the spotlight.

Colter felt as if his former teammates no longer trusted him. Northwestern’s campaign had worked. He polled the room, and it was clear the school would win the election. Even some of his closest confidants from the previous months weren’t with him anymore. Players now questioned his motives: Why had he given them only a day to sign the cards? He also noticed that most African-American players supported the union and most white players opposed it. “There was a huge divide,” Colter says. “The majority of the team was split along racial lines. It was just ugly.”

The players voted on a mild April afternoon. Traveon Henry, a safety, said afterward, “It’s a relief to have it off our plate.”

***

On Aug. 17, 2015, the NLRB in Washington finally issued its ruling on Northwestern’s appeal. The five members unanimously agreed not to exert the board’s jurisdiction over whether Northwestern’s football players were university employees. Perhaps fearful of the consequences of upending the governance of college sports, the board punted. The union ballots would never be counted. The status quo reigned.

What puzzled some observers was that the board did not dispute the fundamental facts of the case—that the players worked long hours under the direction of their coaches and were paid for it. The board even acknowledged the precariousness of the current system. “Whether such individuals meet the Board’s test for employee status is a question that does not have an obvious answer,” a footnote in the decision read.

Colter wrote an email to his former teammates applauding them for having stood up and pointing out the myriad changes already under way around the NCAA. “We played a role in that,” Colter says. “Those guys should be proud.”

Among those changes: In May 2014, shortly before the trial of the class-action lawsuit brought by former UCLA basketball player Ed O’Bannon against the NCAA for licensing his image to video games without compensating him, two companies that had been codefendants with the NCAA—EA Sports and CLC (Collegiate Licensing Company)—settled. EA Sports and CLC agreed to pay $40 million to a class of players who had been on its rosters in video games going back to ’03, the first time any commercial entity had agreed to pay college athletes. In the O’Bannon case itself, Judge Claudia Wilken ruled that the NCAA had violated antitrust law. Schools couldn’t block players from receiving broadcast and video-game money; there was a clear market for their names and images.

Weeks before the trial, the Pac-12 presidents published a 10-point reform plan that included full cost of attendance, lifetime education trusts and improved medical insurance for players. The Big Ten commissioner, Jim Delany, testified during the trial, and days later the conference’s presidents issued a similar open letter. South Carolina, Indiana and Southern Cal unilaterally announced that they would begin handing out four-year athletic scholarships. And the NCAA abandoned its longtime release form for the use of players’ names, images and likenesses. (Schools and conferences now issue the form.) For practically the first time in NCAA history, colleges were tripping over themselves to do better by their athletes.

On the opening weekend of the 2015 season, Colter watched his Wildcats upset a ranked Stanford team and cheered his heart out. He hopes one day to sit down with Fitzgerald. “I don’t think he totally disagrees with everything we did,” Colter says. “If we could talk, we would agree on a lot and disagree on a few things. I’d love for the relationship between Northwestern and me to be fixed, and the good thing is, time heals all wounds.”