Moving out of brother's shadow: Guided to Texas by big brother Dakota, Dylan Haines is creating his own legacy

\n

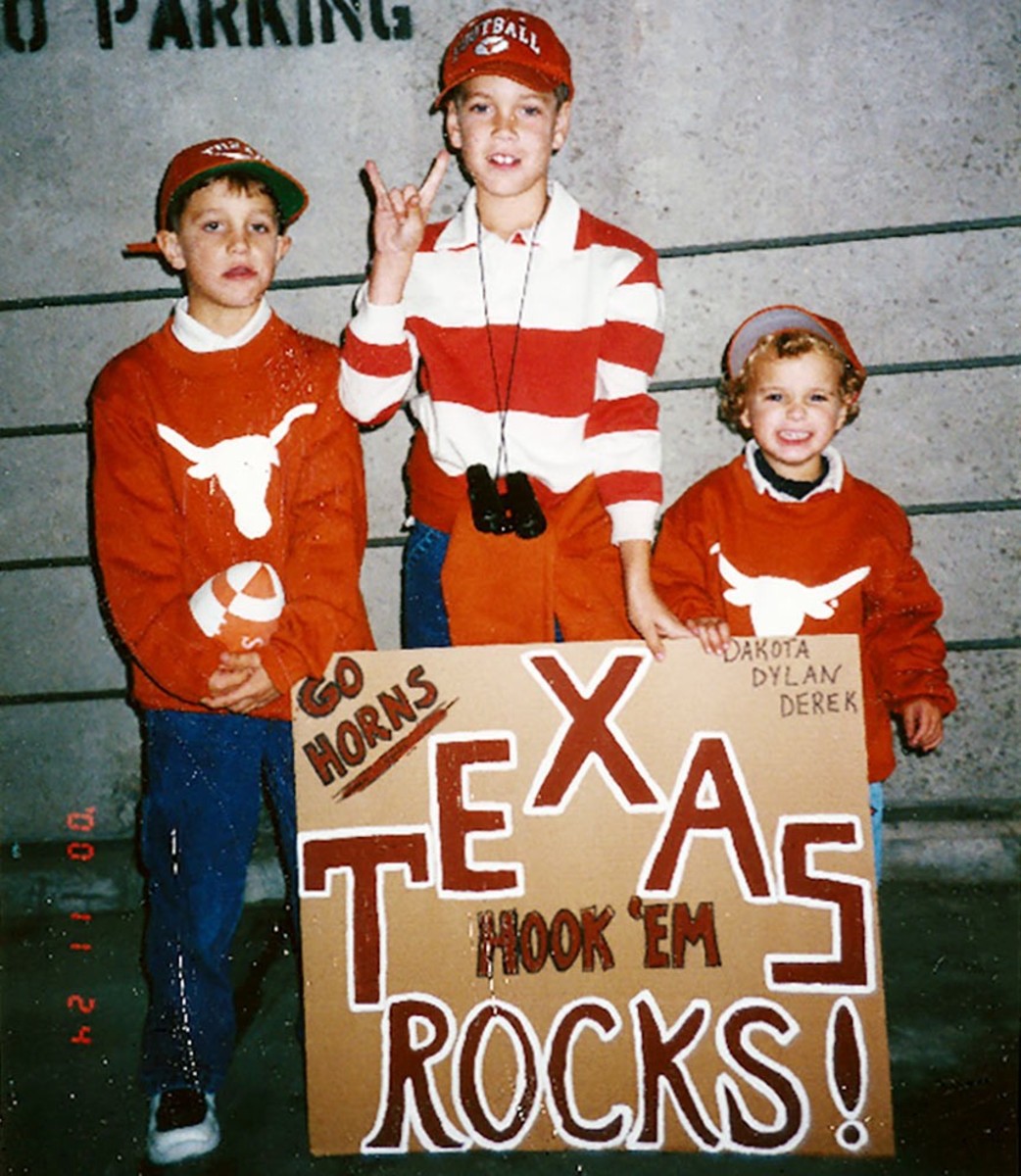

Like most little boys in Texas, Dakota and Dylan Haines grew up in the front yard, playing football and baseball, with some basketball mixed in. They enrolled in Pop Warner—coached by their dad, John—and displayed an instant knack for hitting other people. They attended Texas games and rooted for the Longhorns, a mandate in their house because John was an all-conference defensive tackle at Texas from 1980–83 and their mom, Sandra, was a Texas hurdler and long-jumper from 1976–78.

"Basically, we drug them to games from the time they were born," Sandra says. On the 40-yard lines, twelve rows behind the Texas bench, Dakota and Dylan—who were eventually joined by youngest brother Derek—would watch most of the first quarter, then abandon their seats to play catch underneath the bleachers. By the fourth quarter, they were begging to go home early, bored by the long game.

They weren't exactly diehards, but still had their own thrilling moments. Once, Dakota and Dylan hung over the railing, and former Longhorns receiver Limas Sweed tossed them his gloves. For the elementary school Texas fans, it was "basically the coolest thing ever," Dakota says.

GALLERY: Relive classic 1978 Cotton Bowl between Texas, Notre Dame

Dylan followed Dakota everywhere, desperate to hang out and fit in with the older kids. Those guys were bigger, stronger and better at everything, and Dylan wanted in. If Dakota did it, Dylan had to do, too, whether it was skiing or snowboarding or skateboarding. Naturally, this led to a lot of comparison and a lot of arguments settled by wrestling matches. "I still remember it was all great for a while," Sandra says wistfully. "Then Dylan turned 3 and Dakota turned 5 and from that point, it was all competition."

Recently, Sandra found herself watching some old home videos of the boys, searching for the time 3-year-old Dylan crooned along to George Strait's "Carrying Your Love With Me." "While I'm trying to find that clip all the sudden, on screen, Dylan would be crying because Dakota did something," she says. "I keep fast-forwarding, and he's crying again because Dakota did something else. And I'm thinking, 'Hmm, maybe he got beat up more than I was keeping track of.'"

Like most brothers, they exchanged playful trash talk, with Dakota lording his accomplishments over Dylan. It's Dakota, not Dylan, who holds the record for most interceptions in a season (11) at Lago Vista High in Lago Vista, Texas. It's Dakota, not Dylan, who made it all the way to the state track meet in the 400-meter hurdles, placing second. But years later, little brother finally has one up on big brother: Because it's Dylan who walked on and worked his way to a starting spot and scholarship at Texas.

Now a fifth-year safety for the Longhorns, Dylan has started in 23 of the 24 games he's played in. An all-conference and All-America contender, he'll start his 24 th game Sunday, when Texas hosts Notre Dame in what's being billed as the biggest opening weekend in college football history. Last season he led the Longhorns in interceptions (five) and ranks second in Texas history with 200 career interception return yards.

Not bad for a kid who couldn't even get a Division-II offer coming out of high school.

Dylan, now 22, tells it like this: It's no one's fault, really, that colleges didn't want to offer him a scholarship out of high school. Back then he was 6-foot, 160 pounds with no set position. He played everything at Lago Vista, from defensive back to quarterback to receiver to center to kicker. But versatility didn't appeal much to Division-I coaches, partially because they wondered if his stats (27 catches for 587 yards, 374 return yards, and two interceptions his senior year) were more a result of playing for a small school than superior talent. When Dylan's parents divorced, he moved with his mom to Lago Vista, a 2A school. That's tiny by Texas standards, where most elite prospects are found at 5A and 6A schools. "I kinda felt bad, like I had taken him away from that when I moved to a small town," Sandra says. "Nobody was really watching or looking for any players out here. I felt like he got cheated on that experience."

SCHNELL: Washington State walk-on QB Luke Falk now 'the Messiah of the Palouse'

Dylan was determined to play college ball, so he compiled his own highlight reel and sent it to every college in the state, from Power 5 schools Texas Tech and TCU to Group of Five programs North Texas and UTEP to FCS Lamar. He still has most the rejection emails sitting in his inbox. Meanwhile, Dakota had walked on as a receiver at Texas, then still the home of legendary coach Mack Brown. Remember Dylan's tendency to want to be just like big brother?

"He won't like to admit this, but he likes to do pretty much everything I do," Dakota says. "I mean, everything. Even when it comes to clothes: A few years ago I started wearing the Kanye Yeezy shoe and the next thing you know, Dylan's got three pairs. So as soon I went to UT to walk on, I knew he'd follow."

Dylan told his parents that at the very least, he'd get a great education and be around the program. So he joined as a walk-on and got put on the scout team. At first, Dakota was still there, too, playing the role of little brother's keeper. When Dylan missed a summer workout, coaches yelled at Dakota for letting it happen. When coaches got on Dylan about not hustling on the scout team, John and Sandra scolded Dakota for setting a poor example. Eventually, a torn knee and brutal rehab forced Dakota to end his playing career. Then, Dylan was on his own, with no one to follow.

"I thought if I could just play on special teams, just be on the field, wear the burnt orange jersey, that would be huge for me," Dylan says. "My second year, I'm working my butt off but still limited to scout team, and no one is really taking me seriously."

In reality, Dylan knew the coaching staff wasn't going to invest in a long shot when they had guys with NFL talent on the roster. Frustrated, he told his parents he was ready to transfer to a smaller school and play. Then, Brown announced he planned to retire after the 2013 season.

Recruiting, John Haines says, is an inexact science. As a former college standout and NFL player (he played four years with the Minnesota Vikings and Indianapolis Colts), Haines understands the pressures coaches face to sign top prospects and then win with those kids. And yes, he knows he's partial to Dylan because it's his child—"If you ask my dad, I should be a unanimous All-American," Dylan says, rolling his eyes—but he swears that he's always thought Dylan could hang with the big kids, so to speak, if he were just given a shot. The hiring of Charlie Strong gave Dylan exactly what he needed: a clean slate.

"When Charlie came in, I told, 'This staff didn't recruit any of you from Adam, they're just looking for players,'" John recalls. He says that Vance Bedford, current Longhorns defensive coordinator and a former teammate, marveled at Dylan's instincts and told John, "I can't believe they never gave him a chance before."

By the end of spring 2014, Dylan had worked his way into the rotation. He took regular reps with the starters and had earned a scholarship by the end of fall camp. Signing the aid papers brought more than just financial relief. "It meant that I belonged," Haines says. "My whole life, [people] said, 'You aren't part of that talent group' or 'you're not good enough.' But now …"

Now there was no denying he was. Strong says Haines is "just always in the right place." The third-year coach sees being a walk-on as a bonus because it's given Dylan a relentless work ethic. Even now, as a scholarship player, Dylan knows someone behind him is always angling for his spot, and his role as a starter could disappear any minute. Strong likes how that drives him.

John Rivera/Icon Sportswire

Neither John, Sandra nor Dakota cried when Dylan called to tell them he'd earned a scholarship. But they each have an appreciation for what it takes to succeed at the Division-I level and say they ooze pride whenever Dylan runs on the field.

For years, Sandra got to enjoy games purely as a fan, with no real attachment or afterthought of the final score. Now, she gets the typical mother-of-the-player butterflies and can't always stomach close games. But it's a trade she's happy with. They all are. "My mom always tells me that some of the best years of her life were watching me play in college," John says. "And I get it."

It's special, too, because of whom they share it with. Dakota attends every home game to cheer on his little brother, still sitting in those same seats 12 rows behind the Longhorns bench. The family says Dylan's been successful not only because of a tireless work ethic but also because all those years ago, Dakota let him tag along and showed him how to compete.

THAMEL: How many games does Strong need to win to earn another year at Texas?

Dylan's Texas debut was thrilling, if initially anticlimactic: "The first play against North Texas I'm on kickoff. I get to run on the field, there's 100,00 people, I'm in a Texas jersey, not just a practice jersey but a real Texas burnt orange jersey," he recalls, talking slowly and obviously lost in the memory. "It was a really special moment." At the kickoff, he burst down the field … for nothing. Touchback. "But I ran to the sideline with a lot of energy," he laughs.

His highlight came a few plays later, when he subbed in on a nickel package. In just his third collegiate snap at one of the most tradition-rich programs in the country, Haines picked off the North Texas quarterback, returning the interception 22 yards.

"I'll never forget that," he says. "I remember everything about the play: I'm over on the right side, playing a deep half, a Cover 2 look. I kinda draw back on the snap, and the QB looks over the middle at this shallow crossing route. I break over the top of it in case he catches it. The QB throws a little high, and the receiver tips it right to me." But after that, it's a blur. Dylan knows he ran for a while before being tackled, and he remembers the deafening roar of those 100,000 fans. When he got to the sideline, his teammates fell on him in celebration, slapping his helmet and behind, whooping and hollering, lifting him up. Lost in the euphoria of the moment, "I didn't even know what was going on," he says.

He has photos from that day to help remind him of how far he's come, to chronicle the journey from unknown to undeniable. And it's made better by the fact that he did it, at least partially, because of his big brother.

Know a good walk-on story in college football? Lindsay Schnell wants to hear it. Email her at SIwalkon@gmail.com.