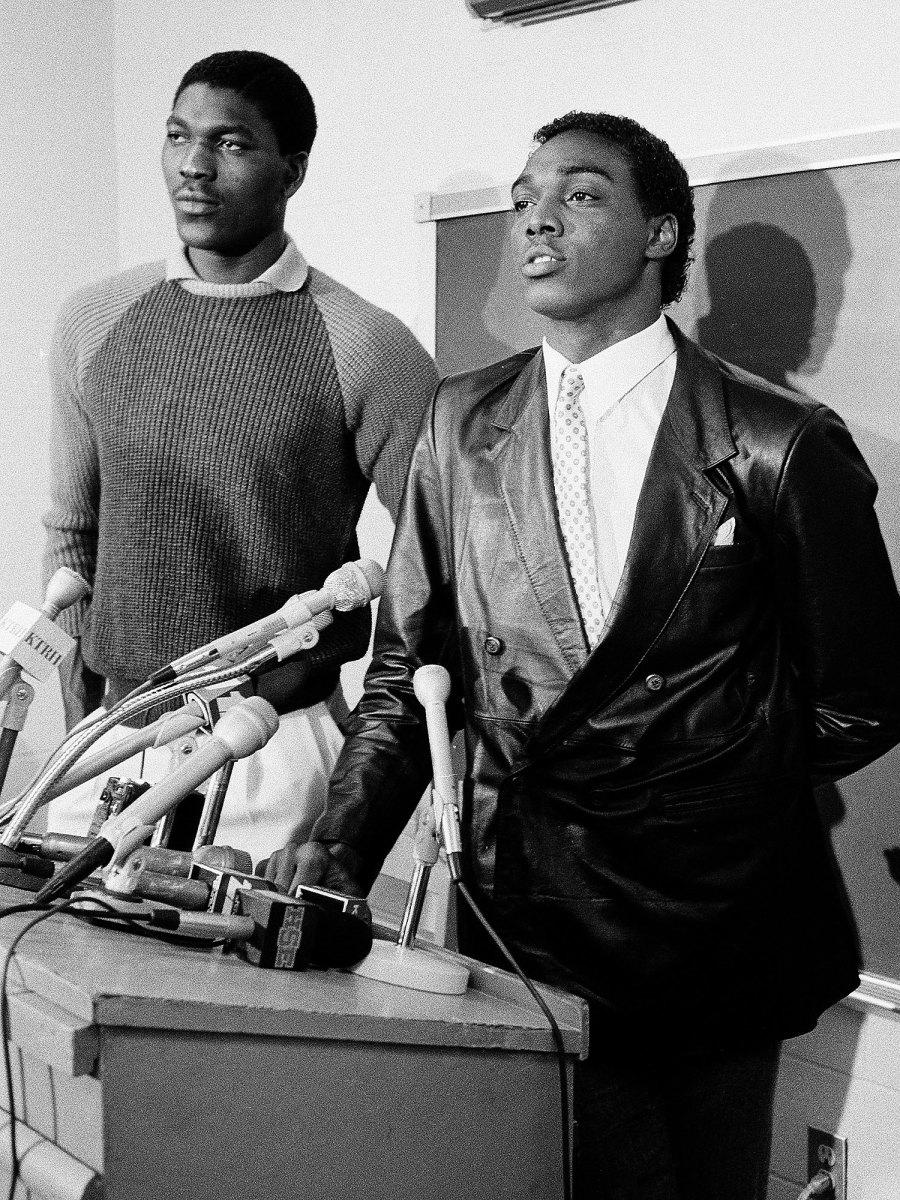

Benny Anders is Alive!

There he is, endearing as ever. He’s not in the Philippines or Switzerland or Swaziland (much less in prison or dead) as had all been rumored. No, he’s on the sidewalk in suburban Detroit, on his way to work at a restaurant. He looks good, too, weighing far less than 350 pounds, as was rumored. He still has a knack for the one-liner. Sitting in all black, his face shrouded by sunglasses, he says at the end of the new documentary, Phi Slama Jama: “A brotherly love is a very powerful thing.”

A dutiful account of the endearing, anti-gravitational Houston Cougars of the 80s— who dunked their way to three straight Final Fours—Phi Slama Jama is a forthcoming “30 for 30.” And it succeeds as a piece of filmmaking. Aided mightily by recollections from the program’s former PA announcer, Jim Nantz, the film’s director Chip Rives gives the viewer plenty of backstory about this unlikely dynasty. (Discussion for another time: can a team that won zero NCAA championships still be dynastic? We think this qualifies as an exception.) We get the Phi Slama Jama fraternity history, an explanation for how this collection of mostly local recruits—a 7-foot Nigerian notwithstanding—came to prominence. We end up with a heightened regard for Guy Lewis, a twanging proto-Tarkanian, who gambled with talent and tactics and usually won. Until he didn’t.

Still, the documentary’s great revelation is the existence of Anders, thereby solving one of college basketball’s enduring mysteries, a conundrum that had confounded everyone from Anders’ former Houston teammates to his own family. (And yours truly: more on this later.)

If Clyde Drexler and Hakeem (then Akeem) Olajuwon were the Otter and Boon of Phil Slama Jama, Anders was Blutarsky, the ungovernable life of the party who added so much color to this cast. A heroic dunker, Anders also had flamboyance to cast. He was peerless as a quote. (His warning to Olajuwon—"When I drop a dime to the big Swahili, he got to put it in the hole"—set a gold standard for sports lines.) This was a guy who showed up to the 1984 Final Four wearing a pink tux.

Anders was called the Outlaw. It was even the personalized license plate on his new Camaro. And it was less a cute nickname than an accurate characterization. He operated on the margins, under his set of rules. Relegated to Houston’s bench in 1985, he complained that he didn’t “want to play for no Phil Slama Clappa” and quit the team. While he was eventually allowed back, his career effectively ended when he pulled a gun on a classmate after a pick-up game dispute.

After that, he disappeared. Not it the way we usually discuss it in sports. He didn’t retreat to his hometown to reinvent himself outside of sports. He vanished. His whereabouts were unknown. Among his teammates. Among his relatives in is hometown of Bernice, La. In basketball circles. He was a jheri-curled version of a phantom. As a former Houston teammate puts it in the film, “It’s like he turned the lights out on his existence.”

This was remarkable on a number of levels. For one, it’s a feat to remain anonymous in a time of geotagging and IP addresses and status updates. Also, if you were going to pick an athlete to seek utter anonymity, Anders would have been your last choice.

I know this firsthand. Having recalled Anders from when I was a kid, I wondered a few years ago what had happened to him. When I realized that “Where is Benny?” was already a parlor game, I joined in. And then got sucked in, venturing to multiple states in search of the guy.

After I published a story on Anders in Sports Illustrated in March, 2013, I received various tips. Benny was using the name “Michael.” He was living in Europe. He had facial reconstruction surgery so no one would recognize him. I also had various middlemen contact me about Anders, claiming they could furnish him. The hitch: there was a request for payment. In one recent case, having explained that paying a source violates a cardinal rule of journalism, I was approached with a counter-offer. In exchange for an audience with Anders, could SI barter a page of advertising for an AAU team Anders was looking to launch? Ah, the Outlaw.

Rives and I talked about his project a few years ago and he went through a similar drill. Rightly, Rives reached the conclusion that finding Anders was a pre-requirement for a Phi Slama Jama documentary. (Full disclosure: I spoke with Rives on camera and appear periodically in the film.)

Rives gathered enough clues to conclude that Anders was in Michigan, where his father lived. With the help of Houston teammate Eric Davis, a former Chicago police officer, Anders was traced to a rental apartment in a neighborhood between Detroit and Flint. A stakeout led them to find and then confront Anders on his way to work. (Rives also confirms that Anders was paid an appearance fee after he was found.) Mystery solved.

Questions still remain. We never learn precisely why one of college hoops’ great cult figures chose to live in the shadows for decades. Or what precisely he is doing now. Or what he recalls from his Phi Slama Jama days. Still, the appearance of Anders in the flesh—the confirmation that he’s alive—is the fitting capstone for a soaring film.

As one of Anders’ associates joked to me the other day, “Y’all will have to find a new player from the 80s to go track down!”

Fennis Dembo, you’re on warning, pal.