Slim's Chance: Chris Boucher took an unusual route to D-I but makes the Ducks a serious title contender

This story originally appeared in the Nov. 7, 2016, issue of Sports Illustrated. Subscribe to the magazine here.

A city bus would pull up in the darkness, to the stop at the corner of Lacordaire and des Tulipes in Montreal-Nord, running on the 380 line overnight between 1 and 5 a.m. On some nights an improbably long and rawboned teenager would slide into one of the gray plastic seats, lined with blue cloth. He'd put his headphones on to drown out the whine of the brakes and the compressed air hiss of the doors opening and closing every few blocks as the bus rumbled southwest down Boulevard Henri-Bourassa, the scenery alternating between neon in the windows of drab retail stores and the low-slung, brick apartment buildings set close to the road. Often he'd listen to Bob Marley, the island reggae bringing some sun into his mind, and he would imagine how his life could be different.

Chris Boucher left Saint Lucia on a plane for Montreal when he was five months old. His mother, Mary MacVane, was emigrating from the tiny, French-Creole-speaking island in the eastern Caribbean, to join Jean-Guy Boucher, the Quebecois man she'd met in 1989 while working as a caretaker in Montreal. They'd gotten married, and after Chris was born in Saint Lucia in 1993, they obtained the necessary paperwork in order to make a go of it as a family in Canada. Chris's maternal grandmother thought he should stay behind. Saint Lucia was a free-and-easy place for a boy, and their extended family, much of whom lived within blocks of each other near the capital of Castries, could handle raising him. But off he went to grow up in Montreal-Nord, a tough neighborhood that was a landing spot for many Caribbean and African immigrants. There was supposed to be opportunity in Montreal, but by the time he turned 19 in early 2012, Boucher had yet to find any of it.

He had bounced between multiple high schools and dropped out before getting a diploma. He worked at a St-Hubert restaurant where, as his best friend and former coworker, Morgan Michael Asibey-Bonsu puts it, "Chris was the best grill man. They liked him because he had skills, and he could make a show with the flames." But the job was part-time and minimum wage, just under $10 (Canadian) per hour. And although Boucher spent substantial hours playing basketball in city parks and recreation centers, he had yet to be part of a serious team with a coach. He had grown from 6' 1" at 16, to 6' 8", but was so skinny that with his hair in short dreadlocks, his profile was almost like that of a mop turned upside down, balancing on its end. And he did not always have someone there to prop him up.

• Read all of SI's 2016–17 college basketball preview coverage

His parents had another son and a daughter in Montreal, but divorced when Chris was 9. After the split he lived with MacVane—until he had a falling out with her new boyfriend, who by the time Chris was 15, no longer wanted him around. He lived with his father after that, but they argued over Chris's lack of direction. Jean-Guy had dropped out of school at 14 to work and regretted it; he didn't want his eldest son to go that route and saw little point in all the time Chris spent playing basketball. It's your life if you mess it up, his dad would always say, and Chris became increasingly doubtful that he would ever accomplish anything. He would often sleep at the apartment where Asibey-Bonsu lived with his family, but on the nights that Boucher's plans fell through or he didn't feel like going home, he would catch the 380 bus and ride it to the end of the line, losing himself in his thoughts along the way.

Sure, he and Asibey-Bonsu, an aspiring battle-dancer and musician, had talked about having some genius idea that would make them millionaires, and Boucher had dreamed about making it in basketball. But by 19 he had settled on a more realistic wish list. I'd still be poor, but I wouldn't be on this bus. I'd have a little house, and it would be like when you see a guy on a TV sitcom, where you wake up in the morning and your girl is there, and then you go to a 9-to-5 job, maybe at a video-game store, and you come home and make some food. That would be a good life for me. If someone had walked up to Boucher and offered him that life, he would have taken it on the spot.

If Boucher had been offered what has since come true—four years, four stops and so many miles down the line—he would have found it inconceivable: That he would be a scholarship power forward at Oregon, coming off a junior season in which he became just the third major-conference player of this decade to average at least 17 points, 10 rebounds and four blocks per 40 minutes, with an offensive efficiency rating of at least 120—the others being Kentucky's former No. 1 draft picks Karl-Anthony Towns and Anthony Davis. That he would be the only three-point threat of that trio (he drained 38 last season)—an added dimension that makes him a college basketball unicorn. And that he would already have a Pac-12 title ring and be chasing a national championship as a senior, when SI projects him to be the nation's most efficient major-conference starter, on the No. 4 team in the country.

In 2012 the odds of any of that happening seemed about the same as those of the bus sprouting wings and flying Boucher back in time to Saint Lucia, where he could restart his life on a different track. How was anyone even going to find him? The closest he had come to playing on an AAU team, where he might have been seen by a college coach, was not very close at all: That March he had taken the initiative to fill out an email form on the website of a team called QC United, in hopes of being invited to a tryout.

Boucher entered his name and his birthdate, that he was 6' 8", and added his phone number and email address. He never heard back. That wasn't because QC United's coaches, Igor Rwigema and Ibrahim Appiah, didn't receive it. It was just that they already had around 100 kids signed up for the tryout, needed to pare down the roster and weren't going to make room for an old player who probably meant to type 5' 8" in the height field. The basketball scene in Montreal is so small that Rwigema said at the time, "it's impossible that there's a 6' 8" player here that I don't know about." Appiah agreed; he looked at the form and said, "There's no way this kid exists."

*****

Nineteen years and five months is young in the context of a lifetime, but almost hopelessly old on the time line of a basketball prospect waiting to be discovered. When the most famous Canadian basketball phenom of Caribbean descent, Andrew Wiggins, reached that age, he had already been famous in recruiting circles for five years, played one season on a top U.S. prep-school team and another as a freshman at Kansas, entered the NBA draft and been picked No. 1 by the Cavaliers, and signed an $11 million endorsement contract with Adidas.

On May 31, 2012, some regulars from the Montreal-Nord pickup-game scene had an open roster spot for their entry in the annual Hang Time tournament at Centre Sportif de la Petite Bourgogne, and invited Boucher to join. He accepted, and although his team was blown out the next day by Montreal's most established AAU program, the Adidas-sponsored Brookwood Elite, he showed off his relentless motor in that game, scoring 44 points, mostly by running in transition and fighting for put-backs. Rwigema happened to be in the crowd, and he asked one of his QC United players, "Who is this kid?"

When told it was Boucher, Igor recalled the unanswered, tryout-registration email and began laughing. He went up to Boucher afterward and confirmed that he was the one who submitted the form. "So," Rwigema said, "you really do exist!"

Rwigema and Appiah soon offered Boucher something better than an AAU tryout: a spot on the prep-school team they were starting at Alma Academy, which was still in Quebec, but a 4½-hour drive northeast of Montreal. Rwigema got his start in the province's coaching scene in 2007 by founding a summer team he called the Okapi Ballers, with a roster of players from his Congolese immigrant community in greater Montreal. Rwigema's grandfather, Barthélemy Bisengimana, had been a key member of Mobutu Sese Seko's administration in what was then known as the Zaire. Before the regime was overthrown during the first Congo civil war, in 1996, a 10-year-old Rwigema and his family found refuge in Quebec. His Okapi team grew into an AAU program he named QC United, and Appiah, a Ghanian immigrant who played briefly at High Point University, joined as a coach. They were looking to place their players in a stable living situation and coach them year-round, and Alma was the solution. Boucher says their pitch to him was simple: "You don't have anything happening [in Montreal] right now. If you come with us, we can't guarantee that you'll excel, but you'll at least have the opportunity to do it."

• Scouting report: Everything you need to know about No. 4 Oregon

His parents signed off, in different ways. Rwigema recalls that when he spoke with Boucher's father, "he basically said to me, 'My kid is useless, he isn't going to do anything with his life, but if you think you can save him, go ahead.'" (Boucher's father says he told Chris that Alma would be "a chance to make your life better.") Appiah says MacVane told them, "I'll let you take him, but if anything happens to him, I'm coming to get you." (MacVane declined SI's interview requests for this story.)

Rwigema and Appiah's initial plan was modest: Have Boucher get his secondary-school diploma, then spend two years at Alma in CEGEP—the Canadian equivalent of college prep—before evaluating his options. Boucher was not viewed as a surefire NCAA prospect, or even Alma's best prospect. He was thinking no further ahead than making the current situation work, because it gave him a consistent living and training arrangement after a childhood that even his mother characterized as "unstable" in an email to USA Today last year.

"With all the imbalance in Chris's life," says Appiah, "I don't think he ever had time to map out any plan. When you're thinking about meals or where you're going to sleep, or how you don't want to go to your mom's boyfriend's house or your dad's house, you don't think much beyond today."

But on Feb. 1, 2013, after a 10-hour van trip to Providence, Boucher did something that made his future a subject of great interest for an audience of American college coaches who'd never before scouted him. In a National (technically, international) Prep School Invitational game between Alma and New Jersey's Blair Academy, Boucher scored 29 points—only missing one of his 14 shot attempts—and had 12 rebounds, five blocks and no turnovers. Among the most intrigued onlookers was Mike Mennenga, an assistant at Canisius who had strong Canadian recruiting connections. But when he did his due diligence on Boucher, "it was already a foregone conclusion"—due to his meager academic résumé—"that first, he'd have to go to junior college."

Boucher's basketball progress got him fast-tracked out of Alma and into American juco ball. He and Alma point guard Nicky Desilien left Montreal for New Mexico Junior College in Hobbs, near the Texas border, in the fall of 2013. After their freshman season they transferred together to a more obscure part of the American West: Northwest College in Powell, Wyo. (pop. 6,462), where the main hangout spot is a McDonald's and one of the seven sports the school offers is men and women's rodeo.

Boucher went to the rodeo once, but it was too much of a culture shock. "I just didn't feel like it was my world," he says. He and Desilien played more video games that season than they ever had in their lives, but it was also in that stark environment that Boucher did the work to transform into a big-time prospect, putting up what Mennenga would later describe as "stupid numbers that were bound to translate to D-I." Boucher averaged 22.5 points per game on 62.7% shooting from the inside and 44.4% from deep, and had the nation's third-highest blocks-per-game average (4.7) and its fifth-highest rebounding average (11.8). Teammate Colin May, a guard from nearby Lovell, Wyo., was shocked to find out, midway through the season, that Boucher's organized basketball career was only in its infancy. "He was the best player I'd ever played with," says May, "and it just did not seem possible that he had only been playing for three years."

• Oregon's Dillon Brooks among preseason POY candidates

Northwest coach Brian Erickson says that Boucher, who led the team to a 31–5 record and had a 29-16-11, points-boards-blocks triple double in their penultimate game, in the national quarterfinals, didn't grasp the extent of his progress either. When Erickson texted Boucher to break the news that he'd been named NJCAA Division I player of the year, he didn't believe his coach. "He just didn't realize how good he was yet," Erickson said.

Boucher's Division I recruitment was, like the rest of his story, abnormal. There were naive moments, like the time Minnesota coach Richard Pitino, during a visit to Powell, made a reference to his father, and Erickson had to interject and say, "Real quick: Can you explain who that is? Because Chris has no clue; growing up, he never watched college basketball." Mostly the process was defined by Boucher's desire to have extremely limited interaction with coaches and put off a final decision until the last minute. In May 2015 he verbally committed to TCU, the school that recruited him the hardest, but when the Horned Frogs sent over his national letter of intent, he left it unsigned, went away for a juco all-star game in Las Vegas, and backed off the commitment when TCU hedged by adding another power forward to its class. Mennenga, who'd been hired by Oregon in '14 and "sporadically" recruited Boucher for the Ducks, made a late push to get him to visit Eugene. Boucher came to campus on May 15 and committed that same evening, having been convinced that he was a better fit for the Ducks' wide-open playing style than for the physicality of the Big 12.

Boucher's slow-play of his recruitment was not strategic. It was just how he approached every potential good thing in his life: with a skepticism born from years of having seen things put in peril by ill-timed obstacles. "I've always felt like there's no point in me thinking further ahead, because it might not happen," Boucher says. "You could tell me, in two years you're going to be a millionaire, but who knows—I could wake up tomorrow and go to jail or something. So whatever you'd tell me, I'd never say I don't want that to happen—but I'd be like, we'll see what happens. That's why I'm always surprised when good things come to me."

*****

Robert Beck

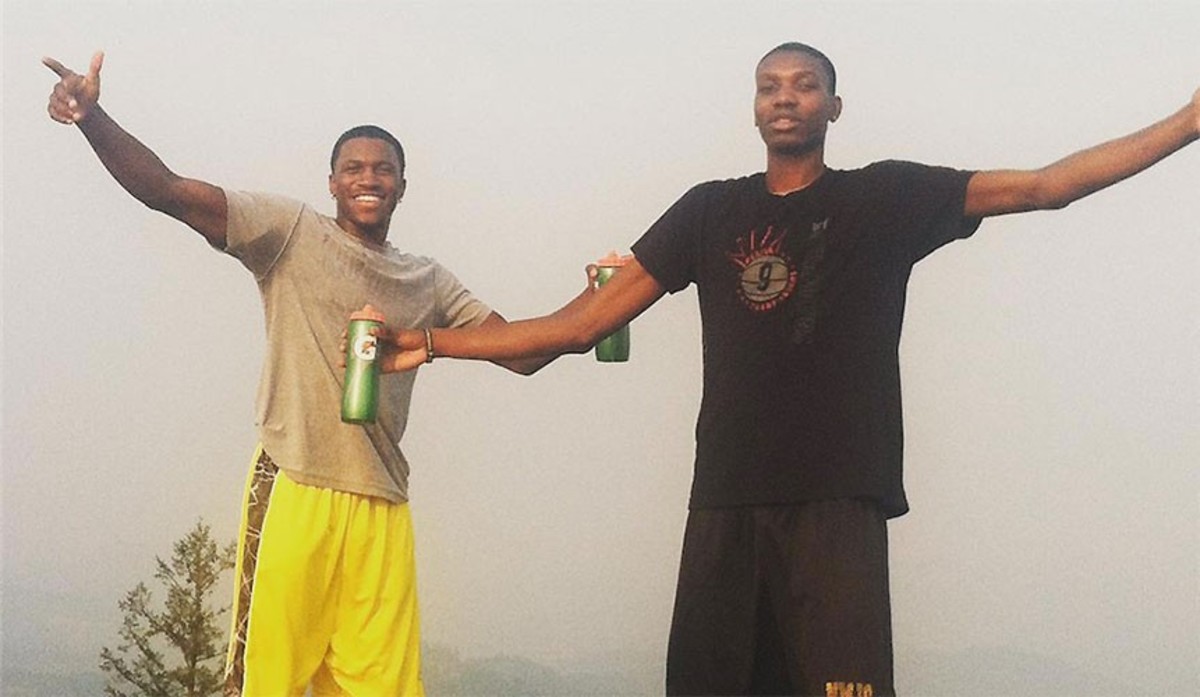

On Aug. 23, 2015, a few days after Boucher arrived on campus at Oregon, Mennenga told him and the Ducks' other Canadian newcomer, graduate transfer Dylan Ennis, that they all were going on a welcome hike.

With the temperature in the mid-80s, they wore basketball shoes, T-shirts and shorts, and headed off in the late afternoon on the trail to Spencer Butte, a popular, one-mile ascent. They hiked up through a ferny and mossy forest of tall Douglas fir that eventually gives way to a naked, rocky summit, 2,058 feet above sea level that offers 360-degree views for miles, including all of Eugene and the Oregon campus to the north.

Ennis already knew Mennenga well—four years earlier the coach had helped Ennis's stepfather, Tony McIntyre, run CIA Bounce, Toronto's premier AAU program—but Boucher was a mystery. "I'd looked on YouTube and couldn't find anything," says Ennis, who concluded that Boucher must've been "literally hiding in Canada" to remain that underexposed. They all sat at the top of Spencer Butte and talked, and Boucher clued them in about his unsteady life and why it was so hard for him to break out. It had taken him all summer—with Appiah and Rwigema pushing him along—to finish the online classes he needed to be eligible for enrollment at Oregon, and Boucher had wept before leaving Montreal for Eugene, knowing that it would be his toughest and loneliest test yet. But there on Spencer Butte, he vowed that he would not blow his chance to thrive with the Ducks.

Mennenga took some pictures to commemorate the hike, and Boucher posted one of himself looking introspective on Facebook that same night, writing, "My life was never easy. Ive work for everything I have right now. This journey is just starting no matter how hard it gets ... believe me ill make it happen.... Nothing is given."

Instagram: @slimmduck

It was not a given that he would make it: Only a handful of juco transfers have a big impact on major-conference teams, and Boucher was still alarmingly bony for a 22-year-old junior, weighing just 169 pounds despite standing 6' 10". He looked, upon arrival, "like a giant praying mantis," walk-on guard Charlie Noebel recalls, and when the team did its preseason strength training, Boucher could barely bench-press 100 pounds. Teammates would crowd around Boucher while he benched and clap while watching his pipe-cleaner arms wobble against the weight.

In part due to an injury to then sophomore forward Jordan Bell, Boucher was in Oregon's starting lineup for its second game of 2015–16, on Nov. 16, against Baylor. He was playing before the largest crowd he'd ever seen, and it was his first time appearing on national TV. (He would call Appiah immediately afterward just to say, for the first of many times last season, "That was crazy.") The Ducks' coaches looked out before tip-off, saw Boucher standing next to his matchup—Baylor's Rico Gathers, who was 6' 8" and 275 pounds and went on to be drafted last April as a tight end by the Cowboys—and Mennenga says, "we were questioning ourselves a little, like, this might be a long night." Boucher's first shot was an open three, from the left corner; he says his nerves got to him, "and my arms were shaking all the way up until the ball left my hand." The ball barely grazed the rim. But the nerves soon faded and the optics of the matchup turned out not to matter, as Boucher finished with 15 points and eight rebounds in an upset victory, while Gathers had nine and four. "What we realized," Mennenga says, "is that nobody he's going against can replicate that motor."

Over and over again during his junior season Boucher's productivity mattered more than his lack of mass. In Pac-12 play, he finished with the league's highest effective field goal percentage (63.2%) and its highest block percentage (12.2% of opponents' twos), and Oregon's defense made a leap from a No. 116 national ranking in efficiency in 2014–15 to 37th in '15–16. With Boucher adding all-around value in support of star small forward Dillon Brooks—a fellow Canadian and a national player of the year candidate—for another season, Oregon can chase its first national championship in 78 years.

• Introducing SI's preseason All-America team

The Ducks' lone title came in 1939, in the first NCAA tournament, for which the final game was held on the campus of Northwestern. That team was nicknamed the Tall Firs; its entire starting lineup was indigenous to Oregon, and its front line went 6' 8", 6' 4" and 6' 4", with the tallest tree being a senior that then coach Howard Hobson called "the best collegiate defensive center I've ever seen": Urgel Wintermute, who went by the nickname Slim. Although Oregon fans nicknamed Boucher Swatterboy, and he's bulked up (relatively) to 200 pounds, his Instagram handle is still Slimmduck, making him a Tall Fir for the 21st century—and the tallest of a crop of Canadians who've been successfully replanted in Eugene.

When Boucher appeared in nationally-televised games last season, culminating in a Sweet 16 win over Duke, what mattered most wasn't the large-scale attention. It was that people back in Montreal could see him as a different person—one who finally had a sense of purpose. Neither his mother, father nor any of his siblings had been able to watch or attend any of his juco games, or travel to Oregon, so, he says, "[on TV] was the first time they actually saw me giving everything I had for something."

Boucher aspires to be a therapist after his playing career is over. In the meantime, he has changed his father's mind about basketball—"I'm very proud of what Chris is doing now," Jean-Guy says—and last summer made it home for a transformational event on the other side of the family. MacVane was getting remarried, to a new boyfriend of whom Boucher—after some natural, initial skepticism—approved. In a small, postwedding reception at the couple's apartment in Côte-Vertu, Boucher, decked out in a purple vest and purple bow tie, said a blessing for them and promised to use basketball to help give them a better life. Asibey-Bonsu was there, and he could tell his best friend was happy to see things genuinely changing. It was just odd, knowing that in order for it to happen, Boucher had needed to step out of the picture. "I feel like everything started to get better when I left Montreal," says Boucher. "My mom didn't have to think about me because I was doing good, and I didn't have to worry about them worrying about me. She was right when she said, 'You just needed a place to go away, and be by yourself and fix it.'"