A Different World: The crazy world of college football in 1966

Imagine a college football season where three of the five top ranked teams didn’t play in bowls, the Heisman Trophy winner didn’t appear on television in the regular season, the two best teams in a major conference didn’t meet on the field and fans had to protest to ensure that the game of the year was televised across the country.

Fifty years ago the 1966 college football season blended drama, frustration and controversy—particularly regarding who could claim to be the best team in the nation. No fewer than three schools, and possibly five, could make a case for the national championship. However, only two schools ended up playing one another, a far cry from how matters are settled today with the College Football Playoff.

Of course, a half-century ago nearly all sports were vastly different. There were no playoffs in baseball, only the World Series where the Baltimore Orioles swept the Los Angeles Dodgers. All four games were played during daylight hours and Games 2–4 finished in less than two hours.

Only six teams comprised the National Hockey League for the 1966–67 season, and the 10-team NBA opened with a new team in Chicago, the Bulls. The 1966 NCAA men’s basketball tournament was a 22-team field limited to conference champions and a few independents. There were hardly any organized women’s collegiate sports.

Only amateurs could compete in tennis’ four major tournaments, and just three golfers (Billy Casper, Jack Nicklaus and Arnold Palmer) won more than $100,000 on the PGA Tour.

The big newsmaker in U.S. sports for 1966 was Kansas freshman track prodigy Jim Ryun who became the first American in nearly three decades to hold the world record for the mile: 3 minutes 51.3 seconds. Two sports legends at the height of their skills, Cleveland Browns running back Jim Brown and Dodgers pitcher Sandy Koufax, announced their retirements.

Who will win the College Football Playoff? Making the case for each team

Then there was college football, where even the best teams and players received little national exposure. Most Saturdays featured only one televised game (usually on ABC), and NCAA regulations severely limited how often schools could appear on TV.

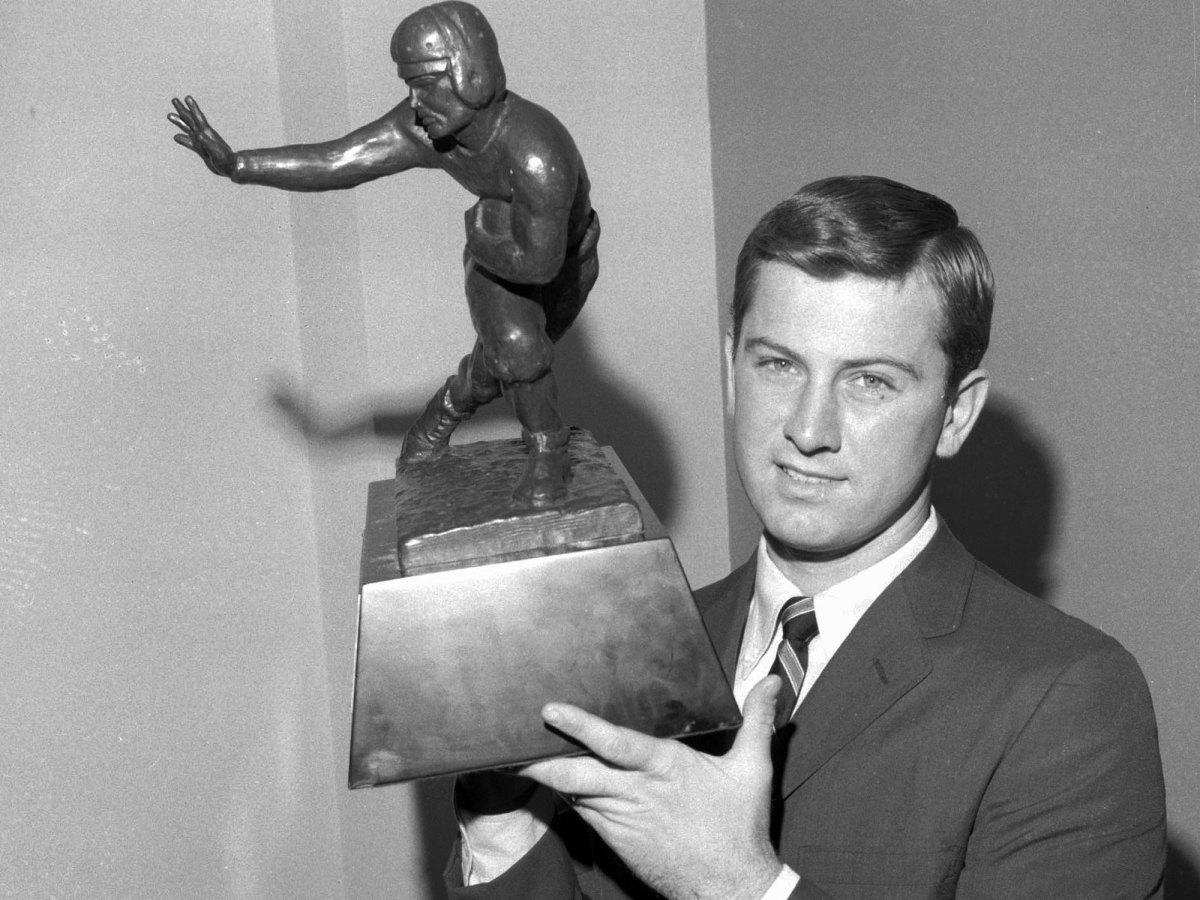

Heisman Trophy candidates relied on word of mouth to burnish their credentials, a formula that clicked for the ‘66 winner, Florida quarterback Steve Spurrier, particularly because none of the Gators’ games was televised. “What really helped me was our sports information director Norm Carlson and Tampa Tribune sports editor Tom McEwen got the word out to Florida sportswriters to spread the word that [the Gators] had a pretty good quarterback,” Spurrier said.

The future Head Ball Coach gave Sunshine State writers plenty of material, completing 61.4% of his passes for 2,012 yards and 16 touchdowns in an era when not many college teams threw the ball. He even booted a 40-yard field goal to beat Auburn, 30–27 as Florida finished the regular season 8–2.

Selecting the season’s top player was a leisurely stroll compared to picking the nation’s top team. Perhaps the only bigger debate in 1966 would have been choosing the year’s top rock record among The Beach Boys’ Pet Sounds, Bob Dylan’s Blonde on Blonde and The Beatles’ Revolver.

Alabama and Michigan State, co-national champions in 1965, and Notre Dame combined to finish the season 29–0–2. SEC co-champion Georgia and Pac-8 power UCLA each suffered one road defeat, the Bulldogs by one point to Miami and its shutdown defense led by future Hall of Famer Ted Hendricks. The Bruins, meanwhile, had proven their mettle at the start of the year, stunning No. 1 Michigan State 14–12 in the Rose Bowl to close the ’65 season.

The Spartans, Fighting Irish and Bruins all played national schedules but ‘Bama and Georgia never left the South. More significantly, they rarely played racially integrated schools. In 1966 there were no black players in the SEC, only one in the Southwest Conference (Jerry Levias at SMU) and very few in the ACC. Even Notre Dame had only one black player, defensive end and future Pro Football Hall of Famer Alan Page.

UCLA quarterback Gary Beban, who finished fourth in the ’66 Heisman voting and would win the trophy in ’67, said when the Bruins visited Tennessee in 1965, the only blacks he saw in Neyland Stadium were the family of UCLA running back Mel Farr.

Beban believes the 1966 Bruins “could have beaten anyone on any given day,” and by early November UCLA trailed only Notre Dame and Michigan State in the polls. But its national title hopes took a major hit with a 16-3 defeat at Washington. Beban said the Bruins were done in by the combination of having to play a third-string center and an unexpectedly wet field at Husky Stadium in Seattle where “it hadn’t rained all week.”

“In 1965, we had used trick plays to beat Washington [28–24], and a lot of people will tell you [an embarrassed Washington coach] Jim Owens pointed toward the UCLA game more than any other that ’66 season,” Beban said. “We had faster players but it didn’t matter on a watered-down field.”

Alabama and Georgia, with a 27–10 win over Spurrier’s Gators, were the class of the SEC but didn’t meet. In that era, SEC schools played only six conference games, and a savvy coach like the Tide’s Paul “Bear” Bryant could limit exposure to dangerous competition. ‘Bama stopped playing Georgia after the ’65 season and rarely played Florida. But it always found room for Mississippi State and Vanderbilt.

Blowing up the BCS: The oral history of the 2007 Fiesta Bowl

“When Florida played Alabama in 1963 and ’64, we went to Tuscaloosa two years in a row,” Spurrier said. “I remember asking our coach Ray Graves why we didn’t get a home game, and Graves said ‘That’s the only way Bear Bryant would play us.’ Bryant ran the conference.”

The ’66 game that overshadowed all others was the titanic Notre Dame-Michigan State battle of unbeatens in East Lansing on Nov. 19, the No. 1 Fighting Irish vs. the No. 2 Spartans.

The level of talent on the field was staggering. The rosters featured 25 All-Americans and 31 future pros. Four Spartans (No. 1 overall pick defensive end Bubba Smith, running back Clint Jones, roverback George Webster and wide receiver Gene Washington) were selected in the first eight picks of the 1967 NFL-AFL draft. Seven Irish players were drafted in the first three rounds.

As black southerners, Smith and Washington (both from Texas), Webster (South Carolina) and MSU quarterback Jimmy Raye (North Carolina) couldn’t play for major universities in their home states and had to take their talents to East Lansing.

Amazingly, ABC did not plan to televise the game nationally. NCAA rules limited schools to one national appearance per season, and Notre Dame already had appeared in its opener against Purdue. The game of the year was scheduled to be blacked out in portions of the South and West Coast. Amid national outrage, ABC was persuaded to show the game in all but two states, thus preserving its label as a “regional telecast.” For the first time, a college football game was telecast live to Hawaii (home of Michigan State kicker Dick Kenney) and to U.S. troops in Vietnam.

Defenses dominated. Michigan State jumped ahead 10–0 (helped by a 47-yard field goal by Kenney) but Notre Dame rallied behind backup quarterback Coley O’Brien to tie the game early in the fourth quarter on Joe Azzaro’s 28-yard field goal. Azzaro later missed a 41-yard try, and the game remained 10-10. ABC analyst Bud Wilkinson sensed a stalemate was likely and lamented that there wasn’t “some mechanism to settle games of this magnitude.” Alas, overtime would not come to college football for another 30 years.

Notre Dame had one last shot, taking over on its 30-yard line with 1 minute 10 seconds left. Fearing a turnover that could give Michigan State prime field position, Irish coach Ara Parseghian chose to run out the clock with four running plays. “Tie one for the Gipper” screamed Notre Dame’s many critics but Parseghian was defiant. Fifty years later he told ESPN, “We didn’t play for a tie. The game ended in a tie.”

Michigan State’s season was over but the Irish had one game left. They made the most of their opportunity, annihilating a banged-up Southern California team, 51-0. Trojans coach John McKay, incensed because he believed Notre Dame had run up the score, vowed to never again lose to the Irish. He nearly pulled it off, going 6–1–2 before leaving USC for the NFL.

Notre Dame (9–0–1) finished the regular season No. 1 in the final polls, Michigan State (9–0–1) was No. 2, Alabama (10–0) third, Georgia (9–1) fourth and UCLA (9–1) fifth. Surely the bowls would help clear matters. But the ’66 bowl season might have been the least satisfying in college football history. Seldom have so many good teams stayed home.

Notre Dame had a no-bowl policy until 1969, making the Irish the last national champion not on probation to skip the bowls. Michigan State was barred from a second straight Rose Bowl appearance by the Big Ten’s no-repeat rule, which stayed in place until the early 1970s. Runner-up Purdue, whom the Spartans had defeated 41-20, went instead. In addition, the Big Ten, as well as the Pac-8, did not allow conference schools to play in any bowl but the Rose.

UCLA’s case was more complicated. Despite losing Beban to a broken ankle in the next-to-last game, the Bruins finished with a 14–7 victory over USC. Surely, they were headed to the Rose Bowl, particularly after Notre Dame incinerated the 7–3 Trojans.

But a scheduling quirk left UCLA with a 3–1 conference mark while USC stood at 4–1. The conference, then known as the Athletic Association of Western Universities, was expanding from five to eight members with the additions of Washington State, Oregon and Oregon State and schools did not play the same number of conference games.

In a major surprise, the AAWU athletic directors awarded the Rose Bowl bid to USC. Perhaps the AD’s thought Beban wouldn’t be ready for Pasadena or harbored a grudge for UCLA “stealing” coach Tommy Prothro from Oregon State in ‘65. Whatever the rationale, the UCLA campus exploded in what was considered the school’s biggest non-Vietnam protest of the 1960s.

“We shut down the 405 Freeway at Wilshire,” Beban recalled. “Most of Westwood was closed down. UCLA was a pretty active campus. Between Vietnam and civil rights, we were pretty good at protesting. We had a lot of practice.”

The Rose Bowl, the so-called “Granddaddy of them all,” became more like the second cousin of bowls with a lackluster Purdue-USC matchup.

Alabama and Georgia (both 6–0 in the SEC) could have met for the unofficial conference championship but preferred not to butt heads. The Tide, behind quarterback Ken Stabler’s passing and running, manhandled No. 6 Nebraska 34–7 in the Sugar Bowl while Georgia breezed past No. 10 SMU, 24-9, in the Cotton Bowl.

In the last all-white Orange Bowl, Florida topped Georgia Tech, 27–12. Perhaps the most exciting postseason action was the Sun Bowl where Wyoming, the Boise State of its day, outlasted Florida State, 28–20. Future Miami Dolphins star Jim Kiick ran for 135 yards and two touchdowns for the 10-1 Cowboys.

While college football seemed unable or unwilling to match its best teams, professional football was about to get a major jolt. The first Super Bowl, featuring the NFL’s Green Bay Packers vs. the AFL’s Kansas City Chiefs, was scheduled for Jan. 15, 1967, in the Los Angeles Coliseum. Although it took a few seasons for the Super Bowl to generate buzz with fans, pro football’s dominance over the college game was fast becoming permanent.

A 1966 College Football Playoff format likely would have included Notre Dame, Michigan State and UCLA, along with the winner of an Alabama-Georgia SEC title game. Those kinds of pairings, however, were nearly a half-century away, and the 1966 season remains one of the most frustrating and controversial in college football history.