Will Lefty Driesell ever get in the Hall of Fame?

The Oldsmobile Story

When Lefty Driesell was a young coach at Granby (Va.) High School in the mid-1950s, he sold World Book Encyclopedias door to door. He says his wife made him do it. Lefty had an office job over at the Ford plant, see, made $6,200 a year, good money in those days. He was a bright young Duke graduate with a sense for sale. Good future. Then he decided to follow this fool muse of his and become a basketball coach. His pay was cut in half. His wife, Joyce, just about left him.

“No, I didn’t,” she says.

“You thought about it,” he says.

No, she says, she did not think about it. But she did pack him a breakfast every morning of the summer, kiss him on the cheek, and send him out at 9 a.m. Lefty would load up his ’33 Ford, a car that once belonged to John D. Rockefeller, and he’d go sell World Books door-to-door to the dutiful mothers of Norfolk, Virginia. The company gave him a huge cardboard foldout, four or five feet high, that he would take into these mother’s living rooms. Lefty liked that cardboard cutout. Years later, when he was recruiting basketball players to Davidson or Maryland, he’d make his own giant cardboard cutout with facts about the school—numbers of Rhodes Scholars, Nobel Prize winners, basketball top-10 finishes, that sort of thing. Parents would swoon.

Of course, parents often swooned for Lefty Driesell, even when he was selling World Books.

“Lookie here,” he’d say. “Here’s an article on birds. Everything you could ever want to know about birds. I don’t know about you, but there are so many things about birds I don’t know. How do they learn to fly? How high can they go? And this is just one topic of a thousand. Everything you and your child will ever need to know, right there, in these beautiful volumes.”

One day, the World Book people announced a contest, with the winner getting a new Oldsmobile. For every World Book set you sold, you would get one ticket put into the raffle box. Joyce was tired of that ’33 Ford, and she thought a 1954 Oldsmobile 88 would be a wonderful family car.

Well, Lefty always did want to make Joyce happy. He sold more World Book Encyclopedias than anyone in Norfolk. In fact, he sold more World Book Encyclopedias than anyone in Virginia.

“I just knew that we had that car,” Joyce says.

The day of the raffle came. And. . . .

“You know who won it?” Joyce says. “A single school teacher who was getting ready to retire.”

And there, in miniature, is the story of Lefty Driesell. Nobody could sell like he could. But, alas, he never did win the car.

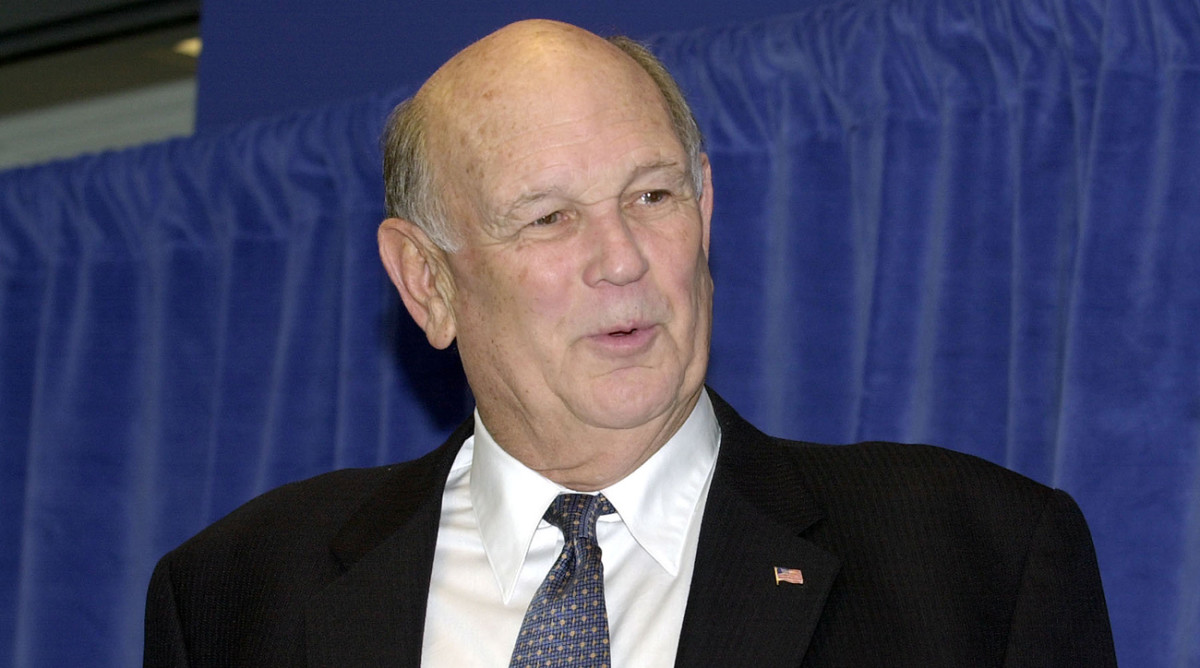

Charles Grice “Lefty” Driesell is back on the ballot for the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame. He’s there every year.

“The greatest program builder in the history of college basketball,” retired broadcaster Billy Packer calls him.

“When you talk about legends and icons in the game of college basketball you’d better include one Charles ‘Lefty’ Driesell,” ESPN’s Dick Vitale sings.

“The man was one of the best that ever did it,” ex-Georgetown coach John Thompson, one of Lefty’s great rivals, says. “He needs to be in the Hall of Fame.”

There are a million quotes like this from just about anyone in the game you can imagine—Mike Krzyzewski, Dean Smith, Lute Olson, Red Auerbach, Jay Bilas, and on and on. Just about everyone in the game believes Lefty belongs in the Hall of Fame. But he isn’t there yet. One more time, he just does not win the Oldsmobile.

Perhaps you are familiar with disruptive coloration. It is a form of camouflage, the sort you see in the military. American soldiers will wear those brown over tan over pale green patterns in the desert, the light green mixed with beige and brown in the woods. They will paint entire jeeps those colors, transports too. Have you ever thought about why this works? It isn’t as if trees or sand are various blobs of color; these transports should not just merge with the background.

But they do, and it is based on the principle that if you break up something with disruptive patterns, the eye cannot quite follow. The eye looks for an outline, something whole to latch onto, and it has a hard time processing all these shapes and colors that just blend into each other. This is true in sports too. The eye easily sees the greatness of a coach like Dean Smith or Mike Krzyzewski, Lute Olson or John Thompson, these men who largely stayed at one school and won championships.

And Lefty? Well, it’s disruptive coloration. He never won an NCAA championship. He never even reached the Final Four. His team lost perhaps the greatest college basketball game ever played (the Terps’ clash with NC State in the 1974 ACC tournament championship), and he just barely missed out on the two recruits that almost certainly would have made his team legendary. His greatest player was also his most tragic, Len Bias.

So what does the eye see? Lefty Driesell is the only basketball coach to win 100 games at four different colleges. That is a magnificent but odd statistic, one that is difficult to get your mind around. Four times in his life, he took over colleges basketball programs that were down and out, college programs where nobody could win. And somehow he won. Oh, did he win, 786 times, ninth in the history of college basketball, more than John Wooden, more than Henry Iba, more than Phog Allen.

And that doesn’t include the time he coached Newport News High (1957 to ’59) to a 57-game winning streak.

All Lefty did was win games, and not while running programs like North Carolina or UCLA or Kentucky where people expect wins. No, he won them at Davidson, at Maryland, at James Madison, at Georgia State. He won those games as the perpetual underdog, and along the way he also invented Midnight Madness, and he almost singlehandedly made Washington D.C. a college basketball town, and he promoted college basketball like nobody else.

How Lefty Driesell started Midnight Madness with a midnight run in 1971

“Not once did he take a program that was already thriving,” Krzyzewski says.

“You look at his records, programs that had zero tradition, from urban environment to suburban to country schools, he won at all of them,” his great Maryland All-America forward Tom McMillen says.

“I believe people lost sight of just how good a coach he was,” Lute Olson says.

“I find it impossible to believe that Lefty Driesell isn’t in the Naismith Basketball Hall of Fame,” Dean Smith said back in 2004. It’s a dozen years later. He still isn’t in there.

The Charlie Scott Story

Lefty Driesell can’t explain to you why he thought that he could win at Davidson. Nobody really had in 20 years. Lefty was just a high school basketball coach selling encyclopedias to make a few extra bucks. And yet he knew.

“All my friends called,” he says, “and they said, ‘Lefty please don’t go to Davidson. You’re going to get fired in four years because you can’t win.’”

Lefty heard them, but he didn’t hear them. The first time he got together with the Davidson alumni group, he told them that he would get Davidson into the Top 10. “They all looked at me,” Lefty says, “like, ‘What, are you drunk?’”

His first team at Davidson, in 1961, went 9–14. And Lefty Driesell would never oversee another losing season in his career.

The Wildcats’ breakthrough game happened in 1963 when they went up to Columbus to play Ohio State. The Buckeyes had been a Top 10 team each of the previous four years and had not lost at home in St. John’s Arena during that span. Nobody had heard of Davidson. But Lefty’s team went up to Columbus and dominated Ohio State 95–73. Lefty had come up with a new offense for that game. Ohio State coach Fred Taylor, a Hall of Famer, had no idea what hit him.

In 1966, Lefty led Davidson to it its first NCAA tournament appearance ever.

Then he made the boldest move of his young coaching life. He signed a 6' 5" basketball star out of New York City named Charlie Scott. The man had everything. He was a New York playground legend. He was valedictorian of his high school class. He also was going to be the first black basketball player at Davidson. With Charlie Scott, he just knew that he could make Davidson the best team in the country.

And then, Charlie Scott changed his mind and went to play for North Carolina and Dean Smith.

How Charlie Scott chose UNC and became the Tar Heels' first black scholarship athlete

“This is the first time he’s signed anything to do with athletics,” Dean Smith giddily told the press when it was intimated that perhaps he had poached a player who had already committed to Davidson. The Charlie Scott story would get repeated again and again. One of the great ironies of Lefty Driesell’s career is that he gained the reputation as a master recruiter and only so-so coach, while Dean Smith’s reputation was as an able recruiter but, more, a brilliant coaching tactician.

“Yeah, that’s funny isn’t it, I was supposed to be this great recruiter,” Lefty says. “And yet Dean got me every time. I was up in Michael Jordan’s bedroom. I barbecued at Phil Ford’s house. I recruited James Worthy. I was supposed to be this great recruiter, but Dean got all the players.”

There was one time Lefty got him. That’s a story for later.

None of Lefty’s recruiting losses to Smith hurt quite as much as Charlie Scott. In 1968 and ‘69, Davidson became one of America’s best teams. Twice, the Wildcats reached the Elite Eight. Twice they were on the brink of breaking through to the Final Four.

The first time, 1968, Davidson led that Elite Eight game by six points at halftime. And their opponent came back led by their brilliant All-America. Their opponent, of course, was the University of North Carolina. And their All-America was Charlie Scott. He drove through the Wildcats’ defense to score the clinching basket as North Carolina won 70–66. That was Dean Smith’s second Final Four.

The next year, 1969, Davidson was even better. The Wildcats went into the Elite Eight, and again they played brilliantly. They led by three-points with two minutes to play. And then their opponent (UNC) and their All-America (Charlie Scott) came back. Scott scored 23 points in the second half—“We couldn’t do nothing to stop him,” Driesell remembers—and hit a 20-foot shot at the buzzer to give the Tar Heels an 87–85 victory.

“Yeah people say all I could do was recruit,” Lefty says. ‘Well, the two greatest players I ever recruited never played for me. Moses Malone went pro. And Charlie Scott just kept breaking my heart.”

The Tom McMillen Story

On the very day that Charlie Scott broke his heart the second time, Maryland athletic director Jim Kehoe found Driesell. Lefty remembers: “I said, ‘I just got knocked out of the Final Four. What am I going to talk about another job for? I have three starters coming back—my whole frontcourt is coming back. Mike Maloy was an All-America. Why in the world am I going to go to Maryland, where you guys can’t win anything?’”

But Lefty wasn’t the only salesman in the world. Kehoe had targeted Lefty, and he knew the exact pitch to use. Vince Lombardi had just been hired as head coach of the Washington football team. Ted Williams had just been hired as manager of the Washington baseball.

“You, Lombardi and Williams” Kehoe said, “will be the three biggest names in Washington D.C.”

Lefty wasn’t immune to that sort of talk. He loved Davidson, but it was small. Cole Field House at Maryland was the biggest basketball arena on any campus in America (and it was filled with magic—this was the place where Texas-Western had beaten Kentucky). College Park, Maryland, was just 15 miles away from the White House. Kehoe brought along a former Maryland all-conference forward named Jay McMillen, a promising young doctor, and Jay said: “Coach, you could make Maryland the UCLA of the East.”

Lefty liked that. UCLA of the East.

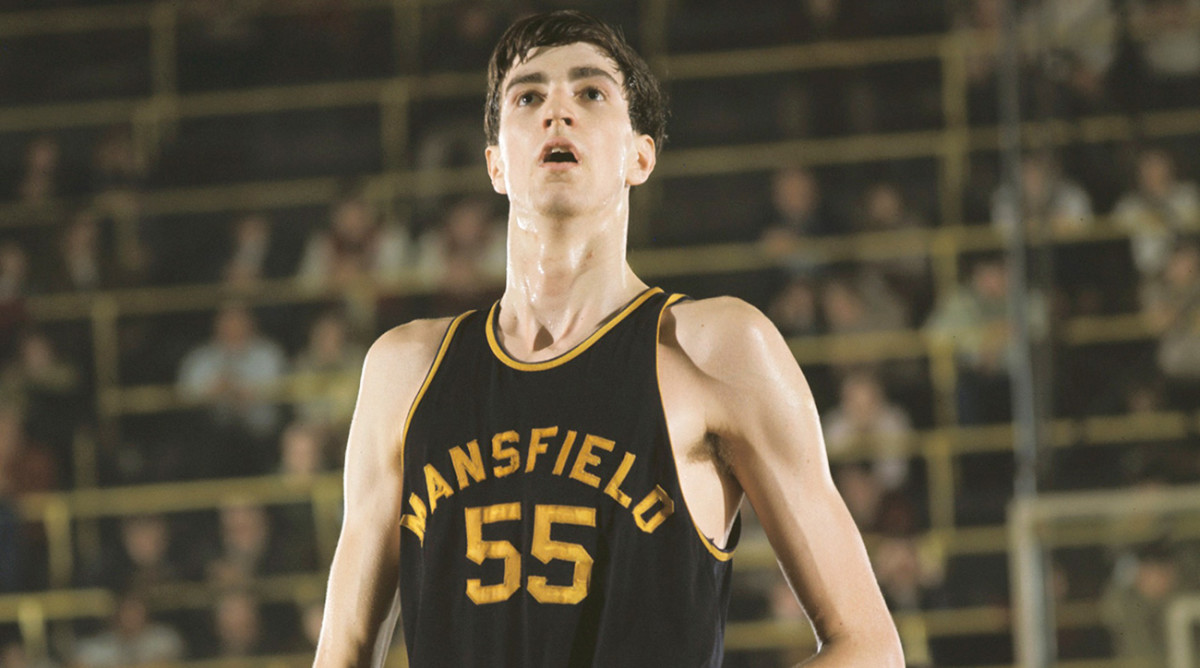

Oh, there was one other thing about Jay McMillen that Lefty liked; he was the older brother of Tom McMillen, the most highly recruited high school basketball player since Lew Alcindor. Tom McMillen was such a good player (he averaged 47 points a game) that he became just the second high school player to appear on the cover of Sports Illustrated. Yes, everybody wanted him.

“It was a different time,” McMillen says. “The rules were lax. Coaches could come to your house 100 times. I think some coaches did come to our house 100 times.”

McMillen, though, was a recruiting puzzle. He and his family could not be swayed by promises of national championships or NBA glory. Schools figured it out pretty quickly. Princeton had the former dean of Harvard Medical School show him around. West Virginia introduced him to President Lyndon Johnson. “I saw operations,” he says. “It’s almost like the doctors were the ones recruiting me.”

• SI Vault: If You Want Tom, Easy Does It

He wanted a school that was progressive but not in open revolt. He and his family wanted a school with a balance between academics and athletics. Any recruiter who talked too much basketball with Tom’s mother Margaret would be rewarded with a dark scowl and an invitation to leave.

Lefty was Lefty. “He was just an incredible force,” McMillen says. “He was like a dog that grabs your pant leg and won’t let go. He’s just unyielding.”

“All I really remember,” Lefty says, “was praying every night.”

And then McMillen made his choice: North Carolina. He just loved Dean Smith. He put in an order for a 7-foot bed in Chapel Hill, and he got ready. It was another Dean victory except . . . Tom had doubts. His parents had both gone to Maryland. Jay was pushing hard. And he couldn’t quite get Lefty Driesell— this self-made man who put his heart and soul into everything he did—out of his mind.

And . . . he changed his mind. Dean Smith was on vacation in Europe when he got the word. Tom McMillen was going to play for Lefty Driesell at Maryland.

“I feel sorry for Dean, I really do,” Driesell told a Charlotte reporter, barely able to hold back his glee. “I know how he feels.”

The Greatest Game Ever Played Story

Those Tom McMillen teams at Maryland were some of the best in the history of college basketball. In those days, there were no at-large bids to the NCAA tournament. In those days, John Wooden’s UCLA won the championship pretty much every year.

In 1972, when McMillen was a sophomore, Maryland lost five times—all ACC road games. The Terps reached the ACC final where they faced a North Carolina team with three players that would be top-10 NBA draft picks. And the game was in North Carolina. All those ACC finals were in North Carolina. The Tar Heels won and Maryland was left going to the NIT where they breezed through to the championship so easily (a 16-point average margin of victory) that they all wondered what was the point.

In 1973, when McMillen was a junior, ACC rival NC State had probably the best team in the country. The Wolfpack were led by perhaps the best college basketball player ever, David Thompson. Driesell had tried to recruit Thompson; didn’t get him, another lost Oldsmobile. NC State beat Maryland in the ACC championship game—Thompson hit two free throws in the final seconds to give the Wolfpack that 76–74 win. This time Maryland did get to go to the NCAA tournament; NC State was on probation for their dubious recruiting of Thompson. Maryland reached the Elite Eight.

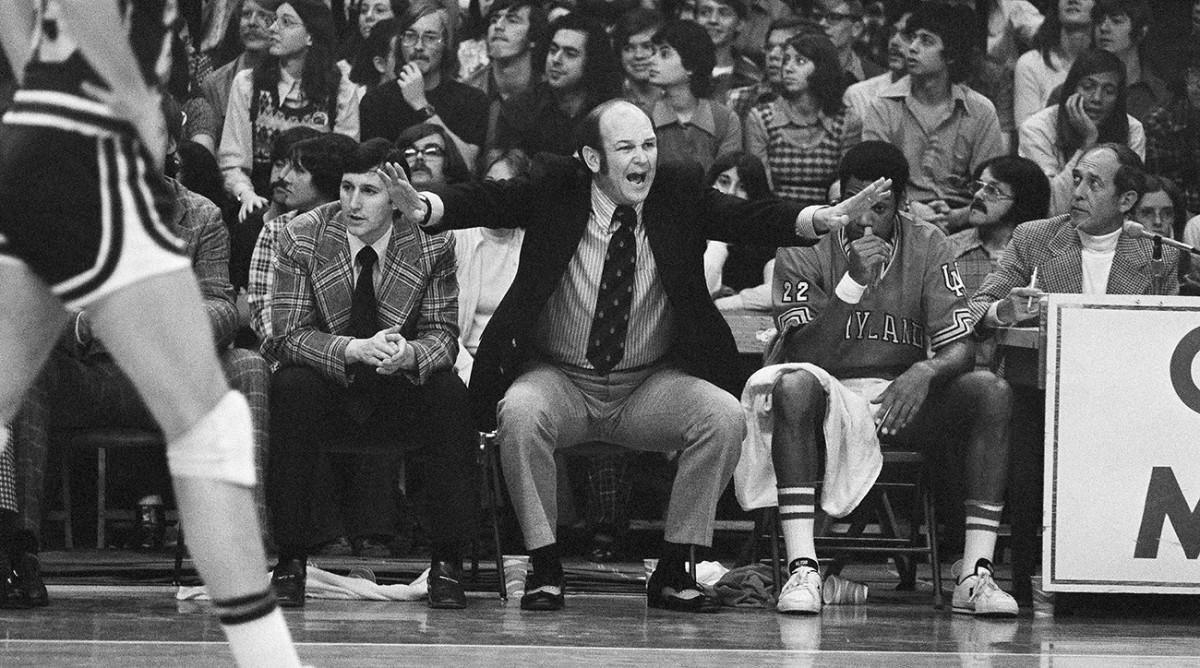

Then came 1974 and perhaps Driesell’s best team. McMillen was joined by All-America forward Len Elmore and a brilliant sophomore point guard named John Lucas. On March 9, 1974, Maryland and NC State played in the ACC championship, a game for the ages. The winner—and only the winner—would go on to the NCAA tournament. Maryland jumped to a 12-point lead. “We were in serious trouble,” NC State coach Norm Sloan would say after. McMillen would make 11 of his 16 shots. Elmore would score 18 and grab 13 rebounds. Lucas scored 18 and added 10 assists. The special defense that Driesell designed for David Thompson was effective; Thompson scored 29 points but was only 10 for 24 shooting.

But NC State had a 7' 4" center named Tom Burleson. He was a terrific but overlooked player throughout his career; he had not even been selected All-ACC. He made everyone take notice that day. He took hook shot after hook shot over Elmore, who could do nothing to stop him. Burleson scored 38. The score was tied in the final seconds.

“I still remember turning around on the bench at one point,” Sloan would say, “and just saying out loud, ‘My goodness, this is a hell of a game.’”

And then Lucas had a shot to win it, but it was an off-balance shot. (“He kind of threw the ball up,” Thompson would say). It did not fall. The game went into overtime.

Maryland was shot by then. It was the Terrapins’ third game in three days (NC State had earned a first-round bye) and Driesell had been forced to use his four best players—McMillen, Elmore, Lucas and Maurice Howard—all 45 minutes. Lucas was particularly drained. In the last seconds, he missed the front end of a one-and-one and committed a turnover. “He was so tired by that time,” Lefty would say. NC State won the game 103–100.

“I’ve never seen a team play better than Maryland,” Sloan said after the game. “It’s a pro team.”

NC State would go on to win the national championship. Tom McMillen would go on to become a Rhodes Scholar, an 11-year NBA veteran and a three-time member of the House of Representatives. Len Elmore, with Lefty’s encouragement, would go on to Harvard Law and a law career as well as a television broadcasting career.

And Lefty? Lefty would just go on. When the Greatest Game Ever Played ended, Lefty went into the NC State locker room to congratulate the winners. “I don’t usually go for that ‘going into the other team’s locker room’ stuff because I think it’s phony,” Driesell would tell reporter John Feinstein. “But that night, I did it. Because I really felt that way.”

The Hero Story

Lefty Driesell kept winning and kept not getting the Oldsmobile for another 20 years after that. In 1975, he signed Moses Malone, who would have joined John Lucas on the 1975 team that lost to Louisville in the regional final. But Malone decided to turn pro instead. “Would we have won a national championship with Moses?” Driesell asks. “What do you think?”

Yes, he kept winning and kept not getting the Oldsmobile. Lefty saw his Midnight Madness idea go national. The idea was pure Lefty. In 1971, he knew that he had a good team. So he got all his players to go on a one-mile run at three minutes past midnight. “You will be the first team to practice,” he told them. “And the last team standing.” More than 800 students showed up to watch. Now, Midnight Madness is an annual tradition. Funny how few remember that Lefty Driesell came up with the idea.

His Maryland career ended sadly; he was forced to resign by the school in the aftermath of Len Bias’s tragic death by cocaine intoxication. Chancellor John B. Slaughter said that despite the basketball team’s high graduation rate, clean record with the NCAA and success on the court, “there needed to be a greater commitment to the development of the young men playing in the program.” In the ensuing years, there have been many arguments around Washington D.C. about whether the Maryland acted fairly or Driesell was scapegoated. Either way, the world never saw Lefty quite the same way.

“The whole Greek tragedy of Len Bias,” McMillen says, “had nothing to do with Lefty. It was a player who made a terrible mistake and paid the ultimate price. I know that Lefty carries that with him all the time.”

Lefty went to James Madison, where his team won five Colonial Athletic regular season titles, but only one tournament championship, which meant only one NCAA appearance (a two-point loss to a Florida team that would go on to the Final Four). He then went on to Georgia State, where his team won three more regular season conference titles and, yes, just one tournament title (his 2001 team went to the NCAA tournament and beat Wisconsin in the first round before losing to, at last, Maryland).

On Jan. 1, 2003, he woke up feeling a bit under the weather. “I turned to Joyce,” he says, “and I said, ‘You know, I’ve been working 49 years. Most people retire after 25. I’m tired, and I’ve got this bad cold, and I’m just going to retire.’”

And, like that, he retired.

There is one more Lefty story, one he does not often tell. In 1973, he desperately tried to recruit a local high school basketball player named Adrian Dantley. It was a typical Lefty Driesell recruitment. “That man,” Adrian’s mother Virginia Dantley would tell the press, “could charm the birds right out of the trees.”

Dantley chose Notre Dame instead. He went on to a Hall of Fame career. Another lost Oldsmobile.

Driesell decided to soothe himself with a Delaware fishing trip. He and a couple of others were on a boat at Bethany Beach when Driesell looked up and saw that four townhouses were on fire. He and two others rushed to the scene and, before the fire department arrived, and crashed into the buildings to warn the people. They saved 10 children that day. Lefty was given the NCAA’s first Medal of Valor.

A Maryland Circuit County Judge named Samuel Meloy was there and he saw it all. “Let’s face it,” he told reporters. “Driesell is a hero.”

“It seems,” UNC student paper The Daily Tar Heel wrote, “he’s really not such a bad guy after all.”

“Aw don’t build me up as any kind of hero,” Driesell would say. “All we did was try to get the kids out. It was lucky that were fishing right in front of the houses.”

But there’s one more part to the story. At one point, Driesell smashed through a door to warn a family about the fire. And the woman, thinking he was a burglar, started shrieking. She ran outside and flagged down a police officer and pointed at Driesell saying that he had broken into her house. The police officer tried to explain what was going on but the women would not listen. It took a long time to convince her that Lefty Driesell really was the hero of the story.