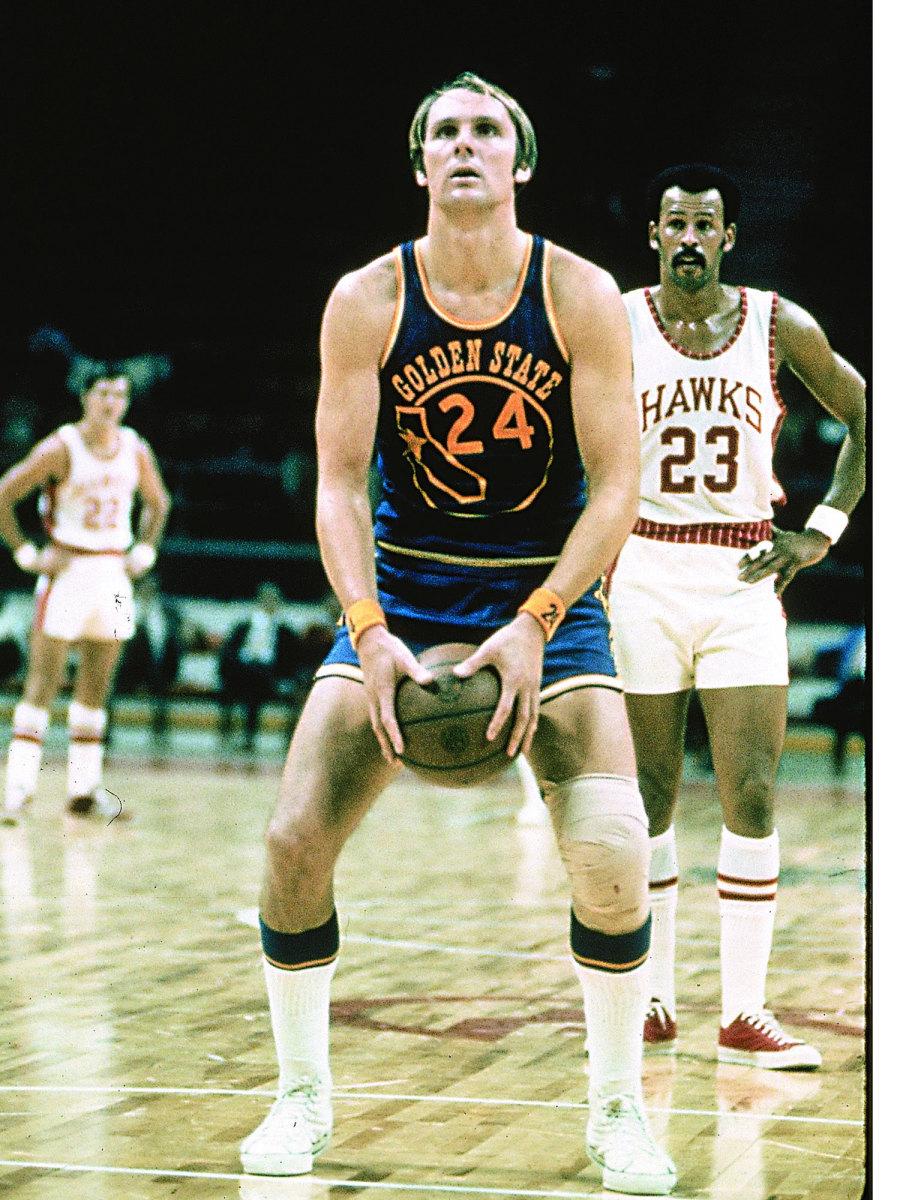

Underhanded Strategy: Florida's Canyon Barry, son of Rick, brings back the granny shot

Like many stories about the Barry basketball family, this one begins with Rick. And he’s right where you’d expect to find him—at the free throw line. It’s an early evening in late January, and Rick and Lynn Barry have walked onto the court at Florida’s Stephen C. O’Connell Center for a photo shoot with their son, 6' 6" Canyon, a senior guard with the Gators. While the photographer assembles his gear, Lynn leads Rick to the charity stripe. “You haven’t shot in a few months,” she says. “I don’t want you to hurt your back. And I don’t want you to miss too many.”

“You don’t have to worry about any of those things,” Rick says before reeling off five underhanded swishes in a row. He sinks the final one with his eyes shut. Even at 72, Rick Barry looks every bit the Hall of Famer he is. Canyon, who comes off the bench but is the -second-leading- scorer for a No. 12 Florida team likely to make the NCAA tournament for the first time since 2014, subs in for his father at the line. He also makes five in a row, underhanded.

Rick is internationally known for his free throw style, and Canyon has revived the technique. Fans leave the O’Dome disappointed if they didn’t catch a granny-style shot. But free throw technique is hardly the most entertaining aspect of being around the Barrys. Throughout the photo session, Rick and Lynn offer as much back and forth as a final set between Federer and Nadal. Lynn playfully teases Rick and tells him not to scowl. “I’ll do it,” he shouts back. “Despite what people think, I am coachable!”

“How about no one talks for five minutes?” Canyon interjects. “You both are in timeout.”

Near the end of a half-hour session, Lynn requests one final photo: she and Rick kissing each of Canyon’s cheeks. “Oh, God,” Canyon jokes. “I’m outta here.”

They all laugh, and Canyon sits between them. After the photographer signals that he’s finished, they walk over to his laptop and begin to beam at what they see: a portrait of a happy family.

*****

Rick Barry was attending the USA Basketball women’snational team practice on Hilton Head Island, S.C., to prepare for an upcoming broadcast when he spotted Lynn’s photo in the media guide. “S---, she’s good-looking,” he remembers thinking. Lynn, a record-setting guard at William & Mary from 1977 to ’81, was working as the head administrator for the national team. A week later they were both in Moscow for the Goodwill Games. The opening ceremonies, on July 4, 1986, was their first date. Rick was so smitten that, three months later, he moved from Mercer Island, Wash., to Colorado Springs, where Lynn was living. Then he called her and said, “I’ve decided I want to spend the rest of my life with you, so I’m going to stay here until you marry me or kick me out.” They were wed in 1991 and had Canyon in ’94. (So named because they believe he was conceived on a rafting trip in the Grand Canyon.)

Rick was a stay-at-home dad for Canyon’s first two years as Lynn traveled the world for USA Basketball. But after the 1996 Olympics she decided she wanted to switch roles with her husband. “Because I was older when I had him, I knew I would only have one child,” she says. “So I decided I’d put everything I had into raising him.”

For Rick, raising Canyon would be a kind of redemption. A 1991 story in SI entitled Daddy Dearest detailed Rick’s shortcomings as a father to his five children with his first wife, Pam—they divorced in 1980—particularly his four sons (Scooter, Jon, Brent and Drew), each of whom played professional basketball. And though Rick and several of his sons later claimed that the article exaggerated his failures, Rick is remorseful about the missed opportunities with his older children. “I regret that I wasn’t with them more,” he says. “They got shortchanged, and so did I. But that was 40 years ago, for God’s sake. I try now to be the best father to my children, the best husband to my wife, the best person I can be to everyone who comes around me. I’m always disappointed that people harp on the past and can’t see me for who I am now.”

From Duke to SMU, Semi Ojeleye's long, crooked journey is finally paying off

As Rick went back to work—hosting a radio show, calling games in Canada, coaching in the CBA and the USBL, and appearing at camps and clinics around the world—Lynn and Canyon traveled with him as frequently as they could. For each trip Lynn would carry a small trunk filled with balls and any other athletic equipment she could cram into it. In airport terminals and taxis and on trains, the family would bounce and throw and catch balls—and occasionally annoy fellow travelers—in Egypt, Israel, Germany, South Africa and all across the U.S.

Basketball did not consume Canyon. When Rick took over for Lynn as Canyon’s primary basketball tutor—around junior high—he realized that hoops would have to compete with his son’s many other interests. One of the first times he taped a game for Canyon to review, Rick had to pause at several points to ask his son to put down his Rubik’s cube. (Canyon can solve one in less than a minute.)

In addition to basketball, at Cheyenne Mountain High in Colorado Springs, Canyon played baseball (for one season and hated it), tennis (winning state team and double titles) and badminton (his team won a Colorado high school club sport state championship); ran track (his team won a state title); learned to surf, ski and slack line; played trombone and euphonium in the band and taught himself guitar; became an Eagle Scout; and graduated with a 4.0 GPA. “My mom wanted me to have a life outside of basketball,” Canyon says, “and I’m grateful for it.”

On the court Canyon handled the burden of being Rick Barry’s son with maturity. He even came to enjoy the hecklers, like the opposing crowd that chanted “You’re adopted” after he missed an underhanded free throw; or the ref who asked him after a trip to the line, “Who do you think you are, Rick Barry?” Canyon silenced the official by pointing to his father in the stands. “Sometimes it’s hard for people to be comparing you to your dad or your brothers, but I’ve always tried to have a positive outlook on it,” Canyon says. “I was blessed with how much my dad has been able to watch me play and be involved in my development. The father-son bond is a special thing.”

*****

A year after Canyon enrolled at College ofCharleston—he took a redshirt season in 2012–13—Rick and Lynn decided to relocate as well. They had grown weary of Colorado winters, so they rented an apartment near campus in Charleston. The first season was far from enjoyable, though, as the Cougars went 14–18 and coach Doug Wojcik was, according to a report issued after a school investigation, verbally abusing his players and bullying his staff. (He was fired in August 2014.) The investigation also uncovered that Wojcik had criticized Canyon and his family. “I’m done with Rick Barry,” Wojcik said, according to then assistant Amir Abdur-Rahim. “I don’t see what the big deal is about your family. Your dad is a [expletive]. I wish you were more of a [expletive]. Your mom is really negative. You’re just like her.”

Rick and Lynn worried that his season under Wojcik would cause Canyon to give up basketball. “When I came in,” says Earl Grant, who replaced Wojcik as coach of the Cougars, “they were concerned that he had lost some of his love for the game. I think Rick and Lynn were looking for someone to put his arms around him.” For his part, Canyon calls the season a “learning experience” but declines to discuss it further.

Enemy Lines: Scouts' takes on the main problems for 15 tournament contenders

Under Grant, Canyon blossomed, increasing his scoring from 9.3 points in 2013–14 to 12.5 in ’14–15 and 19.7 in ’15–16, a season cut short by a left-shoulder- injury. He continued to forge his own path away from basketball as well, earning a degree in physics and taking eclectic electives, including jazz guitar. He would longboard to practice, escape for a surfing trip on weekends off and bring his guitar on road trips. He would spend time with friends from the physics department, a group Lynn and Rick affectionately call the “nerd herd.”

Canyon chose to play at Florida as a graduate transfer partly because he liked the offensive freedom second-year coach Mike White allowed his guards, and partly because he wanted to study nuclear engineering and Florida not only offered the degree but also has an on-campus nuclear reactor. After his basketball career ends—“hopefully a long time from now,” he says—he wants to get his Ph.D. and pursue a career in nuclear energy or radiation detection. “He was a huge get for us,” White says. “He is mature beyond his years. He’s extremely intelligent. As a guy studying nuclear engineering, he’s pretty good at understanding the scouting reports. We’re not offering him the most difficult material he’s dealing with on a daily basis.” And Rick and Lynn—who followed Canyon to Florida and now rent a condo southwest of campus—are at nearly every game.

Graduate transfers can sometimes cause team-chemistry conflicts—especially high-volume shooters like Canyon—but he was quick to accept a different role at Florida. “I remember when I told him he would be coming off the bench,” White says. “I was ready to go into my speech about how he’d made a strong argument to start, but he cut me off. He just said, ‘I’m good.’ That’s how much of a joy he is to coach.”

He is still best known, of course, for shooting his free throws underhanded. But despite the fact that he’s converting at a team-best rate of 89.9% for a group that is 85th nationally in free throw percentage (73.0%), he hasn’t been able to persuade any of his teammates to try his approach. (Barry also set a Florida record with 42 consecutive free throws made.) The only route to getting more underhanded free throw shooters, it seems, would be another branch of the Barry family tree. “The math person in me likes to joke that we doubled in one year our number of converts when [Louisville’s Chinanu] Onuaku switched,” Canyon says. “But now he’s in the NBA and we’re back to just me.”

Bracket Watch: How conference tourney results are impacting the field

Canyon’s free throw shooting style can distract from the fact that he is playing more efficiently than ever even as he makes the jump from a mid-major to a power conference—he’s upped his offensive rating to 120.7, from 98.0. The Gators are 23–6 overall and second in the SEC at 13–3, and Canyon is third on the team in win shares, behind starters Devin Robinson and KeVaughn Allen. After two early losses in conference play, the Gators beat eight consecutive SEC opponents before losing at Kentucky, 76–66, last Saturday.

*****

After the photo shoot, Rick and Canyon played A Game of P-I-G. Lynn discourages the idea—she prefers that they only compete in board games on family game nights—but gives in when they agree to shoot underhanded.

It’s subtle, but Canyon’s technique is not the same as his father’s. For one thing Canyon has modernized the stroke by moving his hands forward so that the ball doesn’t snag on his shorts, which are longer than the kind Rick used to wear. And unlike Rick, Canyon doesn’t dribble. When he was first learning to shoot this way, he decided to ditch the dribble to maximize the efficiency of his practice time. But none of that matters in the short P-I-G game. Rick, ever the competitor, blanks his son, 3–0.

As they walk off the court, Rick tells Canyon not to sweat the loss. “I practice those shots all the time at camps,” he says. “You keep making it from the free throw line.” Later that night Rick says, “I’m proud of Canyon for so many reasons, and basketball is the least of them.” But this story ends with Rick walking away from a free throw line, putting his arm around his son and smiling.