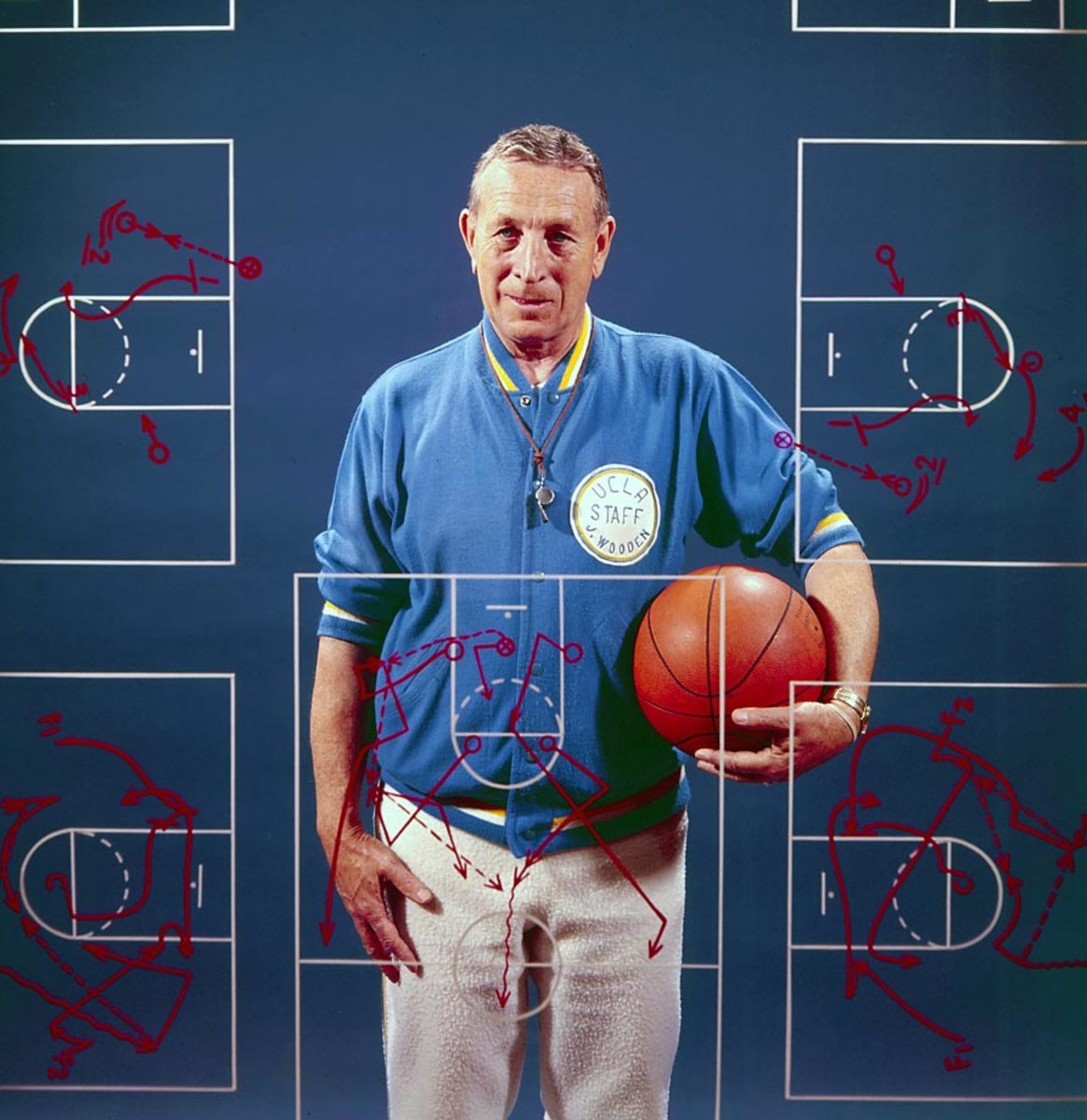

Revisiting the remarkable legacy of John Wooden, the greatest coach of them all

When John Wooden was a high school English teacher in South Bend, Indiana, during the 1930’s, he grew disenchanted when he saw how much the parents fixated on their children’s grades. Wooden believed this was foolhardy thinking. For a student who was not particularly gifted in a certain subject, a B should be considered a fine grade. For another who had more natural ability but did not work as hard, a B should be deemed less than satisfactory.

Wooden was a lover of the English language himself, not to mention a burgeoning amateur poet. As he ruminated on the meaning of the word “success,” he devised his own definition: “Success is peace of mind that comes with the self-satisfaction in knowing you did your best to become the best that you were capable of becoming.” Wooden may have become the most “successful” coach in the history of college basketball, but he never lost sight of what that word did, and didn’t, mean.

From 1964 to 1975, Wooden’s UCLA teams won 10 NCAA championships. That remains an all-time record that is likely never to be broken. Yet, even though he collected more titles than any other coach, he rarely used the word “win” while talking to his players. He wanted them to focus on process, not results. He thought their emotions should remain on an even keel, so he kept his pregame locker room speeches short, to the point, and mundane. He never provided them with detailed scouting reports on their opponents. Once the game began, he didn’t want them looking over to the bench for instructions from him. He rarely called time outs. As their coach—their teacher—he believed his work was mostly done during practices. The games would be their final exams.

Most Innovative Coaches in NCAA Basketball History

Dean Smith

Smith was an innovator on the court and off it. He is the father of modern basketball analytics, and was even a proponent of the shot clock despite his reputation with the four-corners offense. Off the court, he fought for racial equality in North Carolina and across the country.

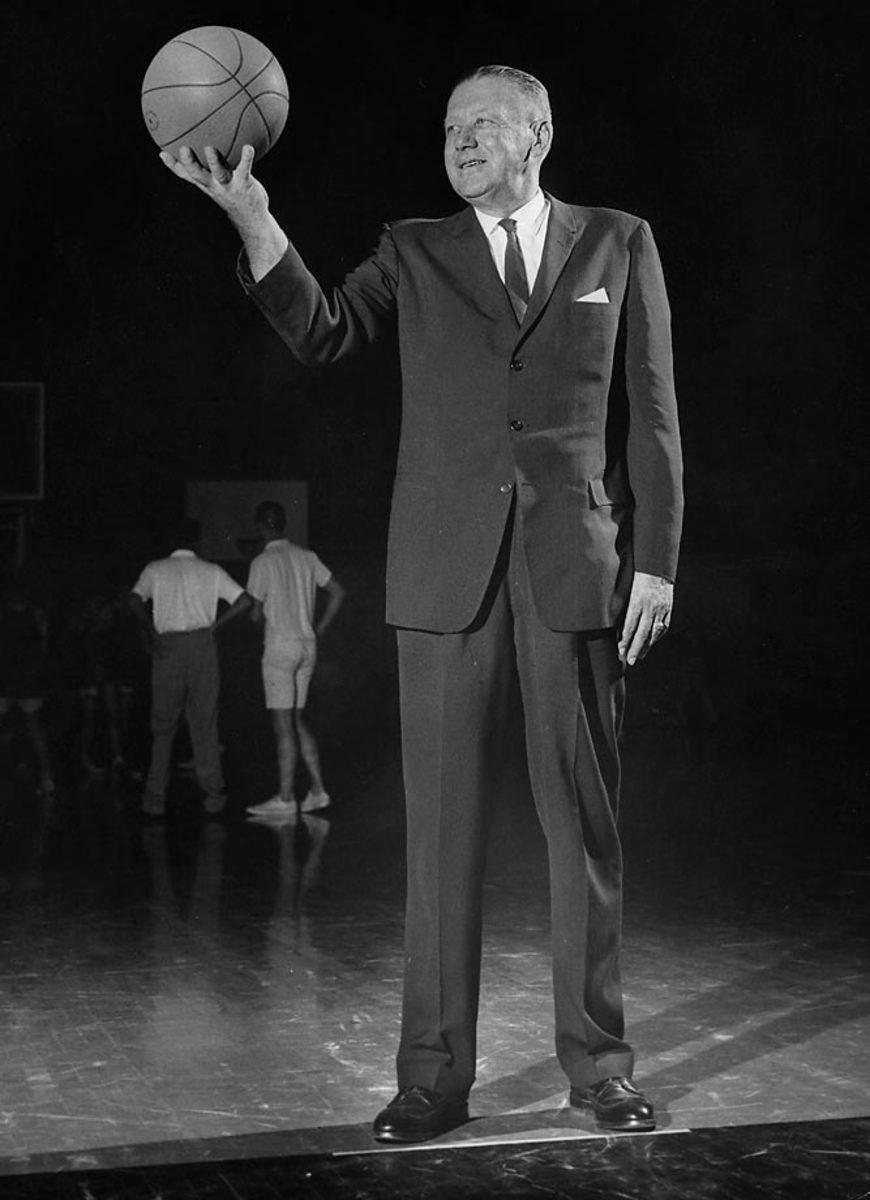

Hank Iba

Although he’s probably best remembered for his work with the U.S. Olympics basketball teams, Iba won 767 games and two national championships during his 41-year college coaching career. He was a proponent of slow-tempo basketball in the no-shot-clock era, coaching his team’s to shoot only when absolutely necessary and to play lockdown defense. His teams didn’t break 50 points in either national championship victory.

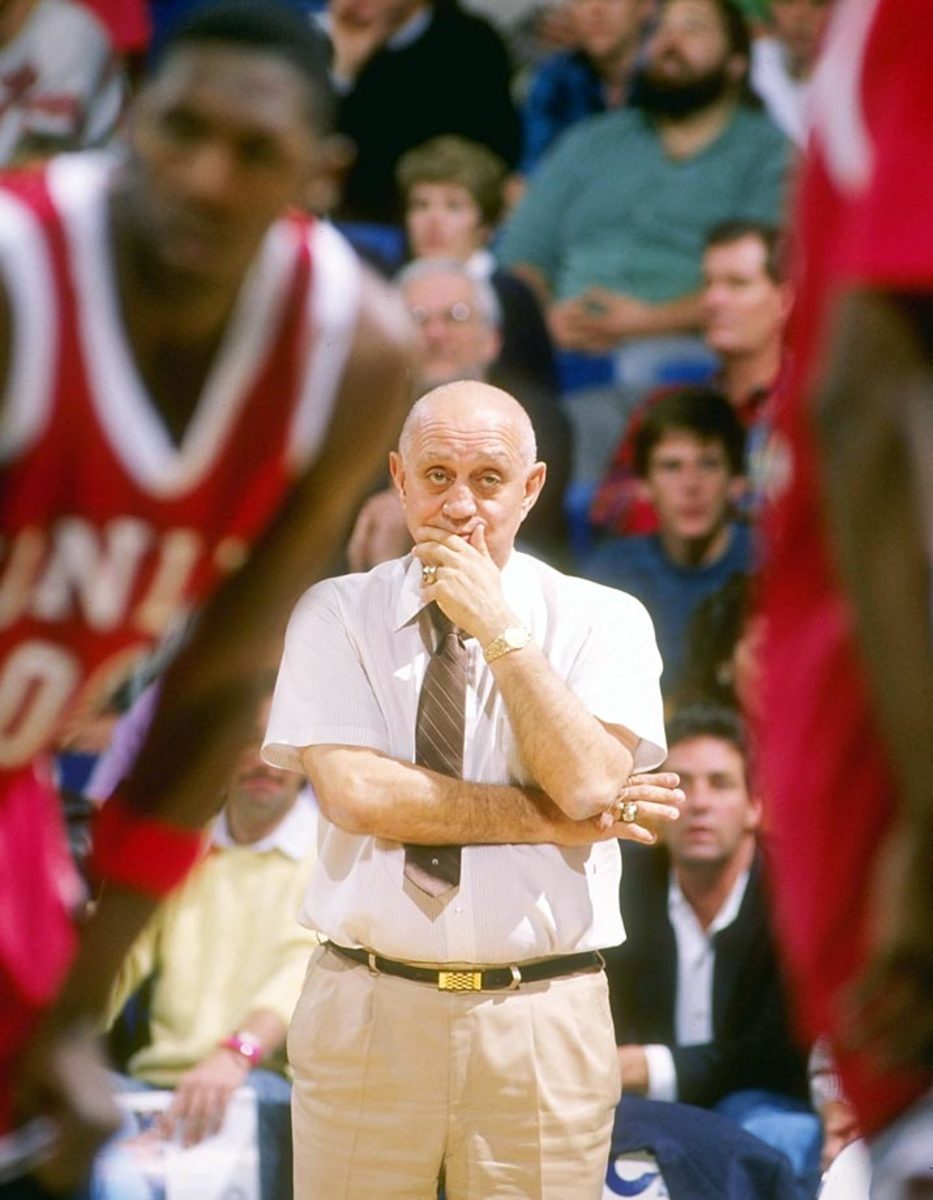

Jerry Tarkanian

Tarkanian’s teams are mainly remembered for being high scoring even before the shot clock, but his biggest contribution to the game may be his amoeba defense. The amoeba defense is a gambling zone that he employed as an off-look from his standard man-to-man defense, and it disrupted offenses. Tarkanian was also an innovator off the court; he was never afraid to point out the hypocrisy of the NCAA. History is slowly vindicating his rebel reputation.

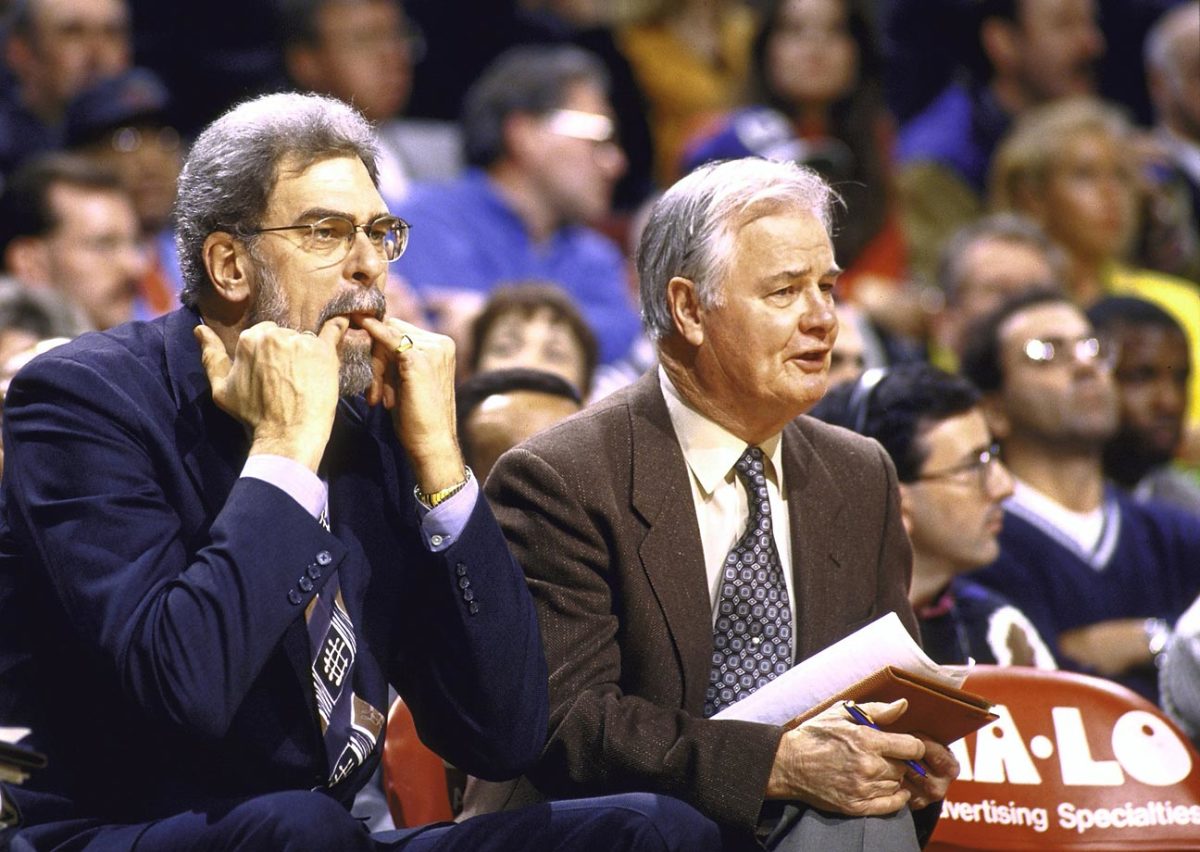

Tex Winter

Although Sam Barry is credited with inventing the triangle offense, Winter perfected it as an assistant at Kansas State. He quite literally wrote the book on the scheme, called The Triple-Post Offense. Although he developed his system in the college ranks, it’s now best known because Winter and head coach Phil Jackson used it to help the Bulls and Lakers win nine NBA championships.

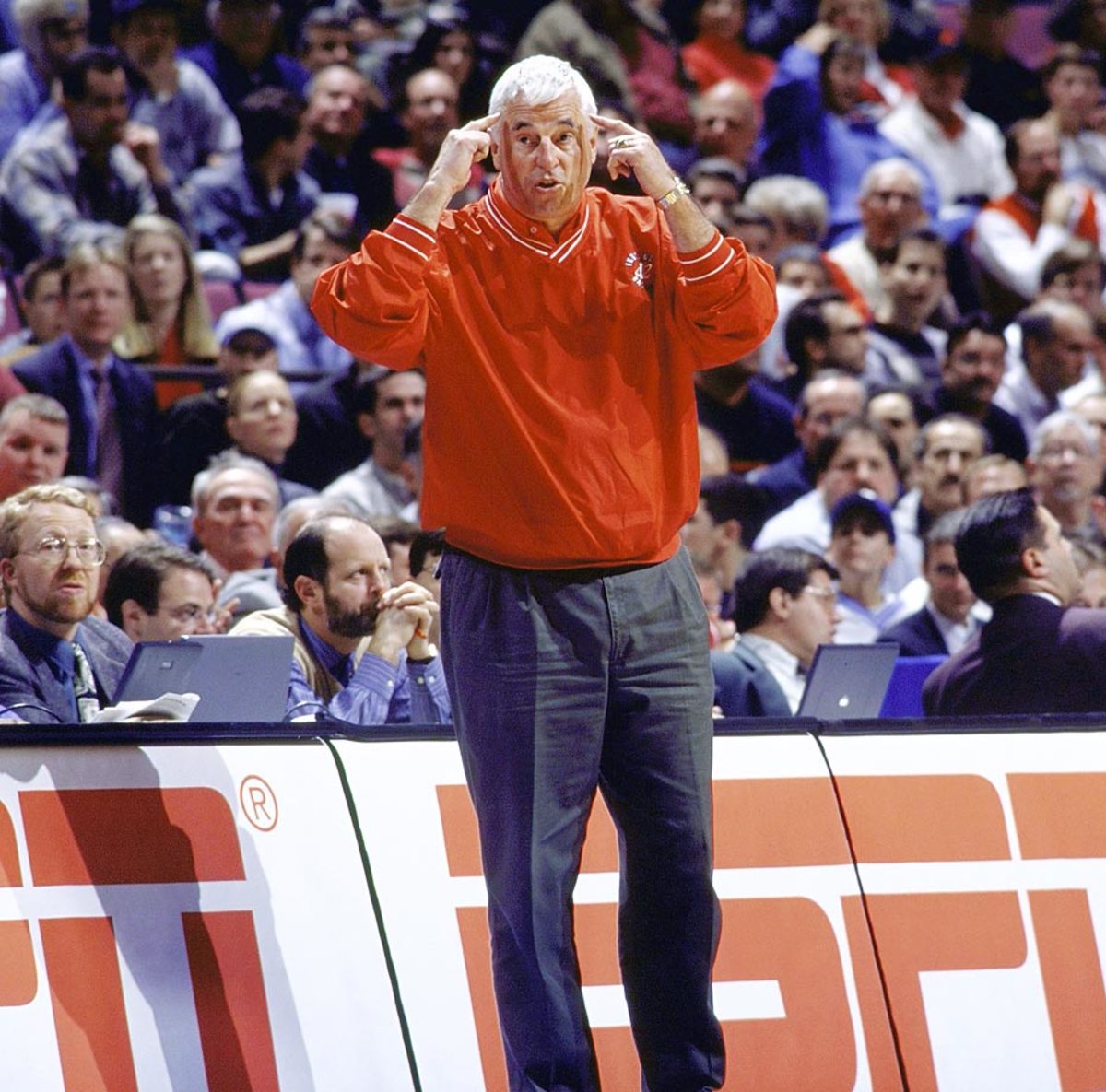

Bobby Knight

Knight developed his famous motion offense after watching Princeton run its offense while he was a coach at West Point. The motion offense revolves around spacing and emphasizes screening, slashing and passing over shooting three-pointers. The elements of this offense are still seen throughout the sport.

Rick Pitino

After the three-point line was adapted in 1987, Pitino became its champion. His ’90s teams at Kentucky were nicknamed Pitino’s Bombinos for their proclivity for shooting beyond the arc. You can understand Pitino’s impact in the size of his coaching tree: 21 former players and assistants have become head coaches.

Pete Newell

Newell achieved most of his basketball success at the end of his career, winning a national championship at Cal in 1959 and then coaching the gold medal-winning U.S. team in the 1960 Olympics. He’s best known, though, for his Big Man Camp. His students included Shaquille O’Neal, Hakeem Olajuwon and Bill Walton. It became the standard destination for big men before entering the NBA draft.

Nolan Richardson

Richardson is the only man to coach an NIT championship, a Junior College championship and a D-I championship during his career. He is best known for his pressure defenses, which were dubbed “40 minutes of hell.”

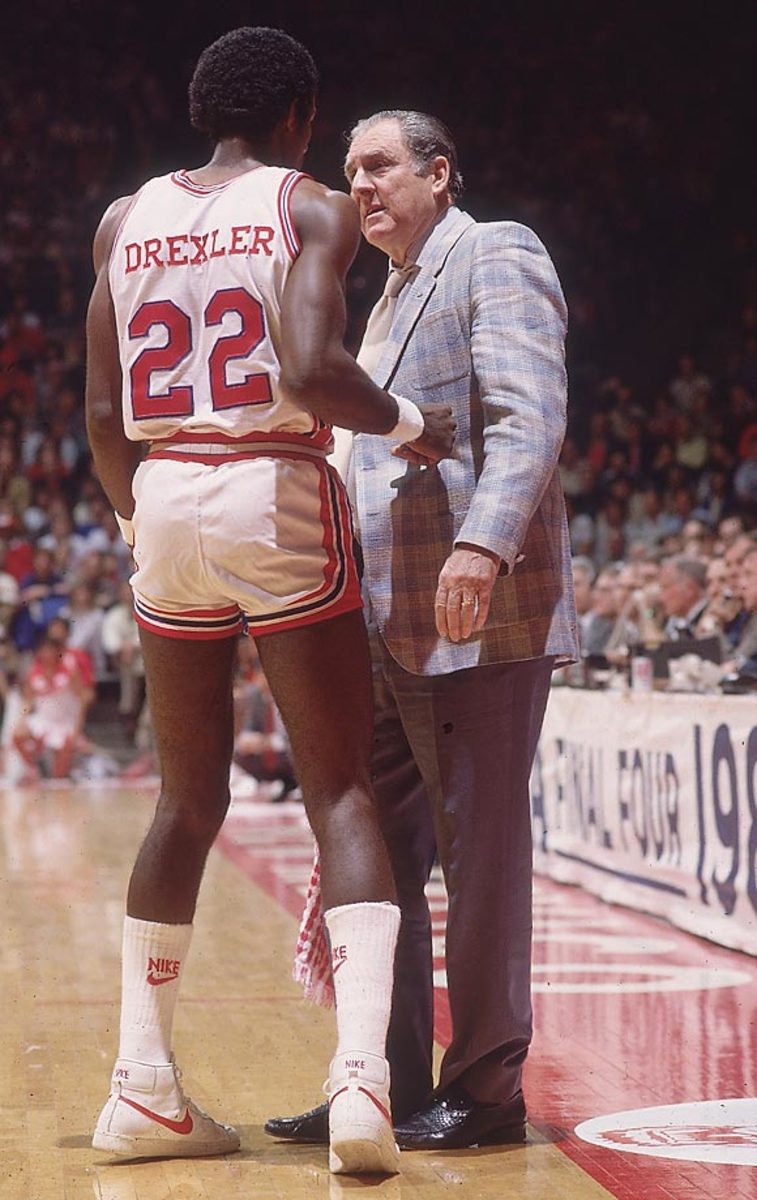

Guy Lewis

Lewis had a near-dynasty at Houston with his Phi Slama Jama teams. His contribution to the game was allowing his players to employ a playground-influenced, freewheeling form of basketball. His contemporary John Wooden considered dunking unsportsmanlike; Lewis insisted that his players dunk.

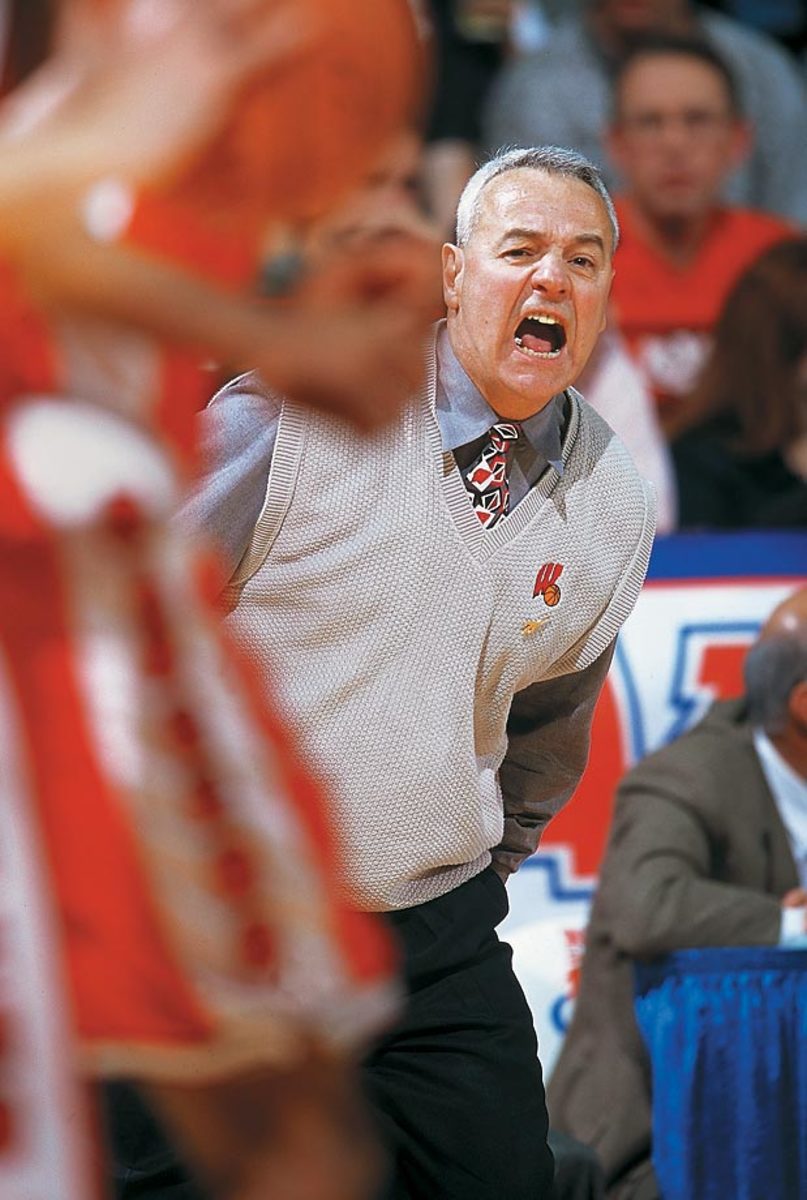

Dick Bennett

Bennett was twice an innovated college basketball coach. While running D-III Wisconsin-Stevens Point in the 1980s, he was an exponent of pressuring, turnover-creating defense. When he moved on to mid-major Wisconsin-Green Bay, he did a philosophical 180 by inventing the Pack Line defense. It’s still widely — and successfully — used today, including by Arizona coach Sean Miller and Dick’s son, Virginia coach Tony.

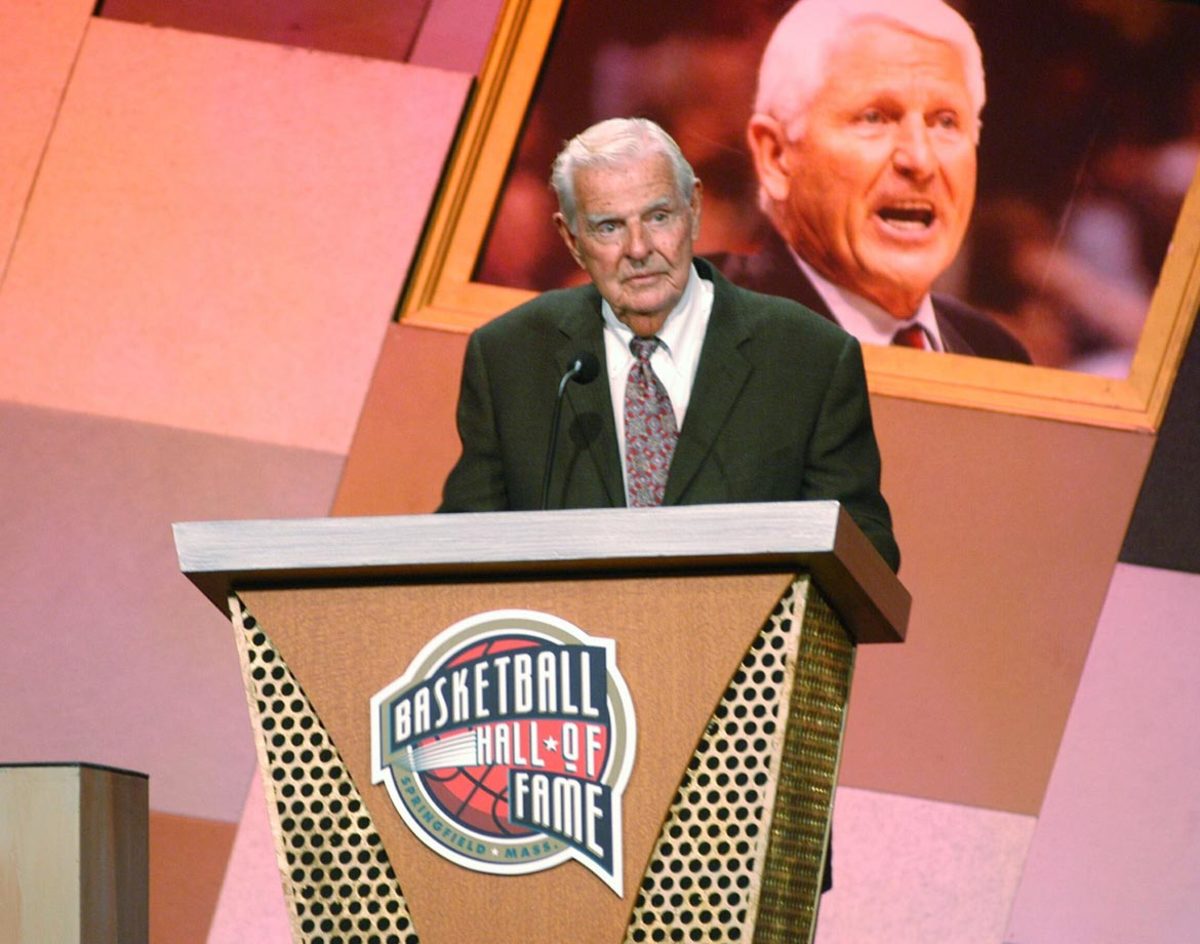

John Wooden

Wooden’s most famous basketball innovation, the 2-2-1 zone press, was actually developed by assistant Jerry Norman, who coached UCLA’s freshman team. They employed it as a way to beat rival Pete Newell, who played ball-control offense. But Wooden’s most lasting innovations are in his team-building, leadership and development. Sports programs and business lessons alike rely on lessons from Wooden to this day.

John Calipari

Love him or hate him, Calipari has been successful at every stop in his career. No coach working right now has embraced the one-and-done era of college basketball better than Calipari. This season, he’s convinced nine former McDonald’s All-Americas to play as a team — and to play no more than 20 minutes each.

This approach to coaching has often been misconstrued as evidence that Wooden didn’t care about winning. That was far from true. He was fiercely competitive, and in his early days at UCLA he developed an unflattering reputation for berating officials. Wooden didn’t avoid the word “win” because he didn’t care about the final score. He did it because he thought it would alleviate pressure, keep his players in the moment, and give them their best chance to maximize their potential. If he had better players, and they played at their best, then he was confident they would win. If they played their best and lost, he could live with that.

In may ways, Wooden was a Zen master before anyone had heard of that term. He tried to stay in the precious present, and he wanted his players to do the same. “There was total structure and complete freedom,” said Bill Walton, who was the star center on two of Wooden’s championship teams, in 1972 and ’73. “He never used the blackboard. We never had a play. There was no number one, no fist, no slash, no come-up-the-court-and-do-this. There was none of that. He never started practice with the word, ‘what do you guys want to do today?’ But he never held us back.”

Enter Here

Cousin Sal Bets The House

Fill out a perfect bracket, win Cousin Sal’s L.A.-area home.

When it came to style of play, Wooden was well ahead of his time. Many of his coaching peers preferred the slow, grinding, defense-oriented style used by men like Oklahoma A&M’s Henry Iba and Kentucky’s Adolph Rupp. Wooden, however, had learned the game while playing for Ward “Piggy” Lambert at Purdue, where Wooden was an All-America guard from 1929–32. Lambert stood only 5’ 5”, yet he had been a feisty player himself for Wabash College in Crawfordsville, Indiana. Basketball was a slow game in those early days—besides being many decades away from the shot clock, the rules called for a jump ball after every made basket—yet Lambert was one of the first proponents of an up-tempo pace that emphasized quickness over size. At the time, that style of play was referred to as “fire wagon baskeball.” Lambert called it the “fast break.”

Wooden was devoted to that style of play throughout his coaching career, but he understood from the start that it would only work if his players were in top condition. This also dovetailed with Wooden’s emphasis on maximizing potential in areas you can control. A player is unable to increase his height, and there is only so much he can do to augment his quickness, but he can work hard to make sure he is in better condition than his opponent. After running his guys ragged in practice, Wooden created a fast tempo during games, and his teams typically won games in the final few minutes because they were in better shape. With that style, Wooden was able to win his first NCAA title in 1964 behind a full-court press and a starting lineup that did not include a player taller than 6’ 5”.

Oregon's Jordan Bell captains Sports Illustrated's 18th annual All-Glue Team

That 1964 team—and specifically the dynamic backcourt of Walt Hazzard and Gail Goodrich—was also a prime example of Wooden’s ability to tailor his motivation techniques to each player, depending on their personalities. Goodrich was sensitive, so Wooden had to give him lots of pats on the back. Hazzard was tougher and played better when he was angry. So Wooden had to pat him “harder and lower,” as he liked to say.

In his later years, Wooden had to find different ways to communicate with Lew Alcindor and Walton, who were arguably the two best players in the history of college basketball but had vastly different personalities. And towards the end of his career, as he faced the campus tumult of the late 1960’s and early 1970’s, Wooden expertly navigated the delicate balance between remaining true to his principles while still adapting to the times that were a-changing.

All too often, Wooden was robbed of his peace of mind during his championship years as he faced unfair criticisms from the press and outsized expectations of the fans. He lost sleep, suffered a heart attack, and enjoyed the job less. That led him to announce his retirement before the final game of the 1975 NCAA tournament, even though he was still as good at his job as ever. That tournament ended with UCLA claiming Wooden’s tenth and final title. The former high school English teacher always maintained that one of the most important words in the English language was “balance.” It wasn’t always easy for Wooden to maintain his even keel, but over the course of more than three decades, he walked away with his balance intact, and a success by any definition of the word.