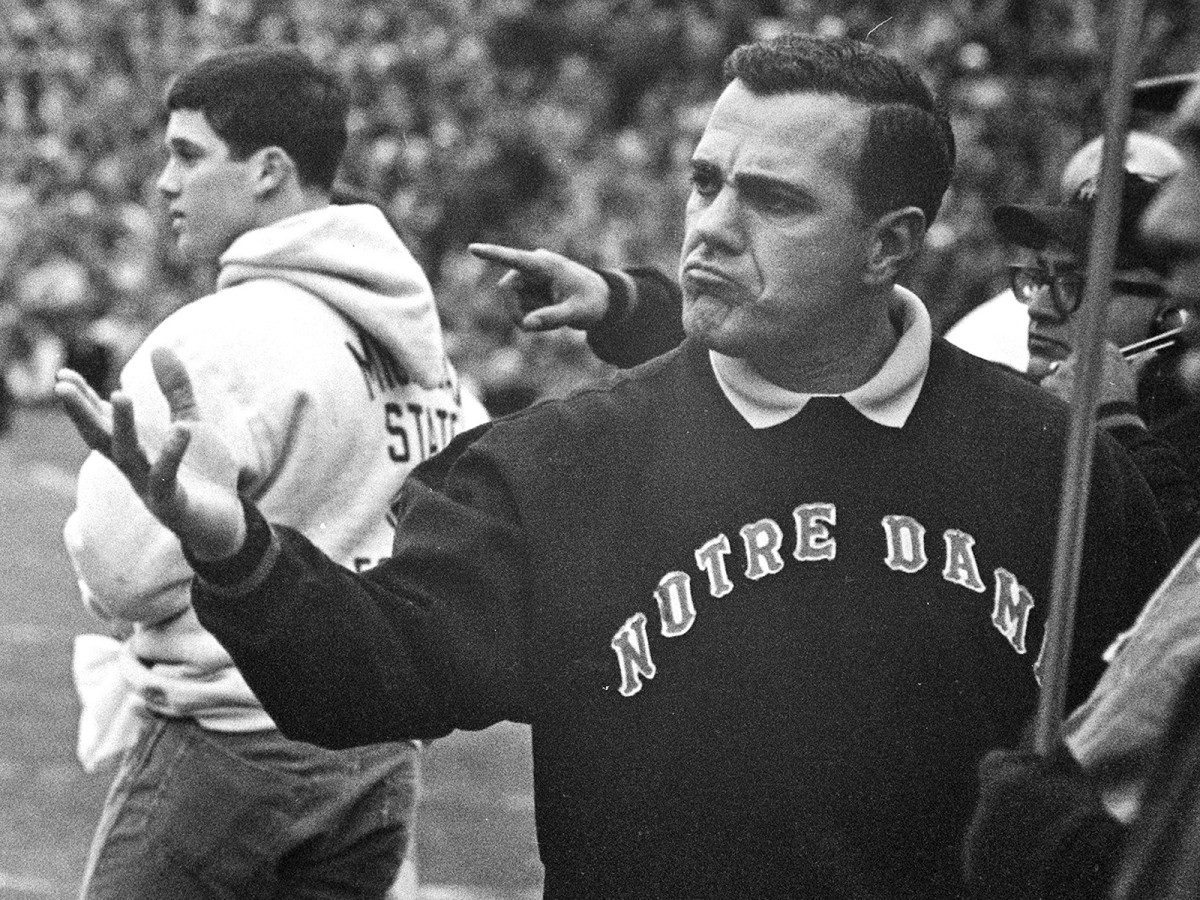

How Ara Parseghian's Big Wins—and One Fateful Tie—Brought Notre Dame Back to the Top

It’s hard to appreciate how low Notre Dame’s football fortunes had fallen before the arrival of Ara Parseghian as head coach in 1964. The Irish had not enjoyed a winning season since ’58 and had gone 2–8 in ’60 and 2–7 in ’63, the school’s two worst records in the 20th century.

And yet under Parseghian, with many of the same players from the previous year, Notre Dame went 9–1 in 1964 and finished No. 3 in the final polls. If not for a 20–17 loss to Southern California in the final game of the season, the Irish would have won the national championship. Quarterback John Huarte was awarded the Heisman Trophy.

The 1964 season served merely was an appetizer for the glory that would follow as Parseghian, who died at 94 early Wednesday at his home in Granger, Ind., led Notre Dame to one of its most successful periods, the so-called Era of Ara.

Between 1964 and ’74 the Irish went 95-17-4 with national championships in ’66 and ’73. Had a College Football Playoff existed back then, Notre Dame likely would have had a shot at No. 1 in ’64 and in ’70. In Parseghian’s 11 seasons, the Irish never ranked lower than No. 14 in the final polls, with nine finishes in the top 10 and six in the top five. To put those 17 defeats in perspective, Lou Holtz, whose Irish won the 1988 national championship and who left Notre Dame with the second most wins in school history, recorded his 17th loss in his sixth season.

Parseghian’s competitive fires burned constantly, and he always seemed in motion. During his eight-year tenure at Northwestern (1956–63), he was known to rouse his Evanston neighbors by mowing his lawn early on Sunday mornings. No one asked if the energetic coach was still replaying Saturday’s game or if he already was beginning preparations for the next opponent.

Parseghian was born May 21, 1923, in Akron, Ohio. His time at the University of Akron was cut short by World War II, and he served two years in the Navy. Injuries kept him from playing for the powerhouse Great Lakes Naval Station team, but Parseghian paid close attention to the squad’s coach, future Hall of Famer Paul Brown, the first of his three most important coaching mentors.

After the war, Parseghian resumed college, this time at Miami (Ohio) where he played halfback for his second mentor, Sid Gillman, one of the pioneers of the deep passing game. Parseghian earned Little All-America honors in 1947.

He had a brief swing at professional football, playing again for Brown, this time with the Cleveland Browns of the All-America Football Conference in 1948–49. He occasionally played in a backfield that featured Hall of Famers Otto Graham and Marion Motley. A serious hip injury ended his pro career in ’49 and a year later he teamed up with his third mentor, Woody Hayes, as freshman coach at Miami.

The Miami frosh went 4–0, and when Hayes moved on to Ohio State in 1951, Parseghian was appointed head varsity coach. He was only 28. Age didn’t matter, as Miami went 39-6-1 over the next five seasons with two MAC championships and an undefeated season (9–0) in 1955.

One of those victories was a 25–14 pasting of Northwestern, and when the Wildcats needed a new coach they hired Parseghian in 1956. At 32 he was the youngest coach in the Big Ten. After a bumpy start, including a horrid 0–9 record in ’57, Northwestern rebounded, only posting one losing season in Parseghian’s final seven years in Evanston. For two glorious weeks in ’62, the Wildcats were ranked No. 1 in the nation following back-to-back victories over Ohio State and Notre Dame, on the strength of an offense featuring quarterback Tom Myers and future Vikings wide receiver Paul Flatley. The Notre Dame game drew a record 55,752 fans to Dyche Stadium. Northwestern finished ’62 at 7–2, the school’s best record for the next 33 years.

The 10 Best Decisions of College Football's Last 10 Years

Parseghian applied one of Paul Brown’s lessons: Ease off on physical practices as game day approaches and switch to emphasizing the psychological and mental aspects of football. His Northwestern teams, although limited by a small recruiting budget and the school’s strict academic standards, more than held their own against more physically imposing opponents.

Despite his success, Parseghian no longer appeared welcome in Evanston. Northwestern athletic director Stu Holcomb indicated Ara’s contract would not be renewed for the 1964 season. “I took them to the top of the polls in 1962 but that was not good enough for Northwestern,” the coach told author Jim Dent many years later.

Parseghian then made a few inquiries at Notre Dame, a school NU had defeated four times in four tries during his Evanston years. He was an unorthodox candidate. The school had not hired a non-Catholic as head coach since Knute Rockne (Parseghian was an Armenian Presbyterian), and he was not a Notre Dame graduate. But Fighting Irish football was in a wretched state, and the school decided to roll the dice.

It was one of the best decisions Notre Dame ever made. “A good coach will make players see what they can be rather than what they are,” Parseghian liked to say and he spent the next decade-plus proving that philosophy. Combining the organization skills of Paul Brown, the offensive imagination of Sid Gillman and the disciplined approach of Woody Hayes, Parseghian built a powerhouse in South Bend.

• SI Vault (1964): After a dormant decade, Notre Dame is once again a national power

Coaching future Hall of Famers defensive tackle Alan Page and tight end Dave Casper as well as NFL All-Pros such as middle linebacker Jim Lynch and quarterback Joe Theismann, Parseghian’s teams were rarely out of the national championship picture. After barely missing out in 1964, Notre Dame had another shot at the national title two years later, in one of the most famous games in college football history—and also one of the most controversial, thanks to a decision made by Parseghian in the game’s waning moments.

On Nov. 19, 1966, No. 1 Notre Dame (8–0) visited No. 2 Michigan State (9–0) in East Lansing for a game that dominated the college football landscape. Special dispensations were required for the game to be televised to most of the nation due to strict NCAA rules that limited how often a school could appear on national telecasts.

The Spartans jumped out to a 10–0 lead, but Notre Dame, behind second-string quarterback Coley O’Brien, rallied to tie the game early in the fourth quarter. With 70 seconds left, the Irish had the ball on their own 30-yard line, seemingly with enough time to move into scoring position. Rather than risk a turnover against a stout Michigan State defense that featured All-Americans Bubba Smith and George Webster, Parseghian ordered four straight running plays, and the game ended 10–10.

“Tie one for the Gipper,” screamed Parseghian’s many critics. The coach answered, “We didn’t play for a tie. The game ended in a tie.”

• SI Vault (1966): How the Notre Dame–Michigan State 'Game of the Century' fell apart

Michigan State’s season was over, but the Irish had one game left, against Southern California. The banged-up Trojans provided little opposition as Notre Dame rolled 51–0 and secured the national championship.

Although the Irish fell short of a title during the next six seasons, their steady success helped end a long-running tradition in South Bend. The Irish had not played in a postseason game since a Rose Bowl victory over Stanford following the 1924 season, but following the ’69 campaign, Notre Dame agreed to play No. 1 Texas in the Cotton Bowl. Although the Irish lost 21–17 in the final minutes, the school was back in the bowl business.

The defeat also showcased Parseghian’s ability to learn from adversity. After the Longhorns’ wishbone offense shredded Notre Dame for 331 yards rushing, the coach tinkered with his defense for the rematch. In the ’71 Cotton Bowl, Notre Dame forced six turnovers and caused the pass-challenged Texas offense to throw the ball a season-high 27 times. Notre Dame won 24–11 and ended Texas’s 30-game winning streak.

Parseghian demonstrated similar acumen two seasons earlier, against another No. 1 team, Southern California. O.J. Simpson had become a national name in 1967 when he ran over and through Notre Dame for 150 yards and three touchdowns in a 24–7 Trojans victory in South Bend. There would be no repeat performance in ’68. A ferocious Irish defense held Simpson to a collegiate career-low 55 yards rushing, and USC was lucky to escape with the score knotted 21–21, which Sports Illustrated described as “a tie Parseghian and Notre Dame could be proud of.”

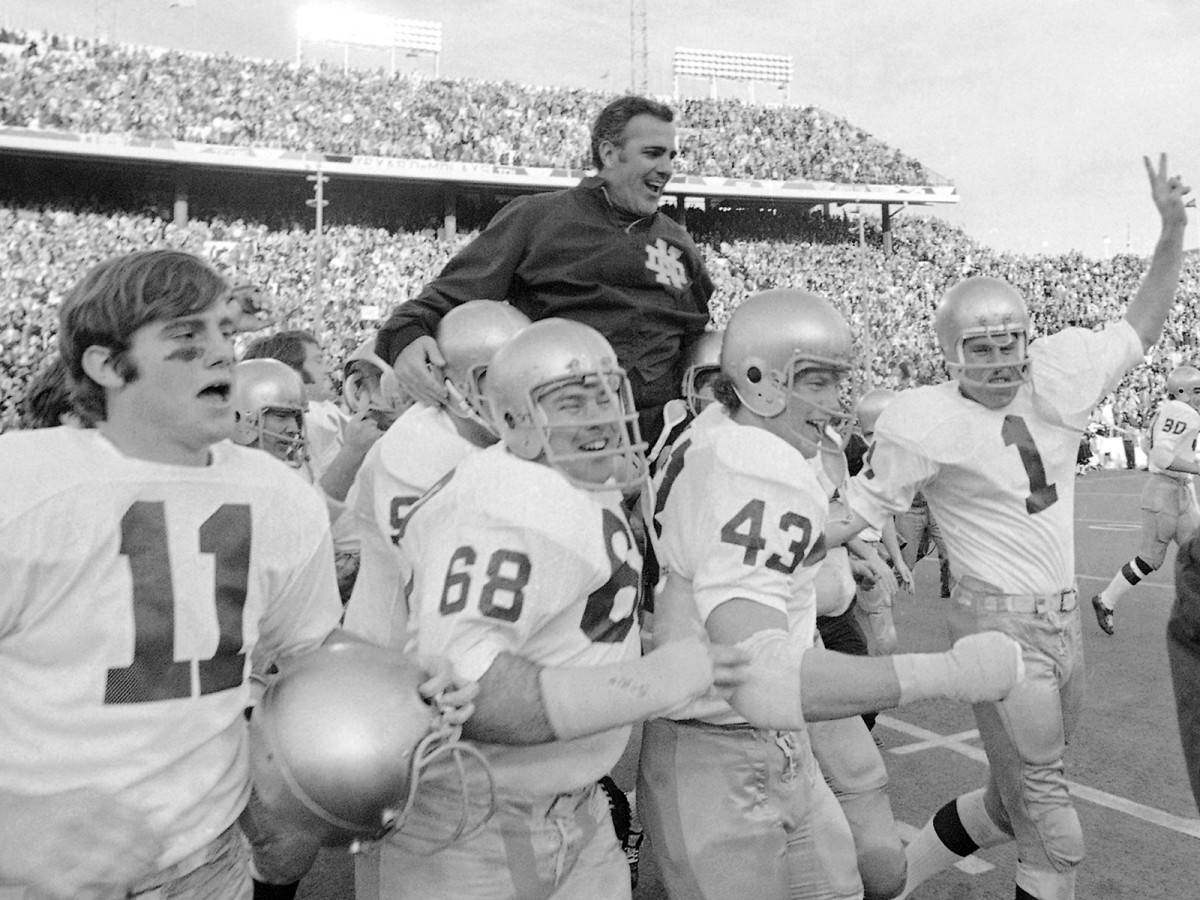

The coach’s best season was 1973, when the 11–0 Irish earned Parseghian his second national championship. To win the national title, Notre Dame needed to defeat No. 1 Alabama and Bear Bryant in the Sugar Bowl—practically a home game for the Crimson Tide. Notre Dame’s regular season was considered suspect, as it had faced only one ranked team (USC) and had feasted on the likes of Northwestern, Rice and the three service academies.

In a game dubbed “Catholics vs. Baptists,” the Irish outgained the Tide by more than 100 yards and edged Bama 24–23. The key play came late in the game, the Irish backed up with third and long at their own three-yard line. Tom Clements threw a 36-yard pass to tight end Robin Weber, and Notre Dame ran out the clock for the victory.

“It’s beautiful,” Parseghian told the Chicago Tribune. “I want to enjoy this for a while.”

Fall Camp Viewing Guide: Seven Storylines Set to Dominate August

But the coach’s days in South Bend were numbered. His hard-driving style was taking a toll on his health. In addition, six Notre Dame players were accused of rape before the start of the 1974 season and suspended for a year. Halfway through the season, Parseghian realized ’74 would be his last on the Irish sideline. Although USC blasted Notre Dame 55–23 in the final regular-season game, the Irish sent Parseghian out a winner with yet another victory over Alabama, this time in the Orange Bowl.

There was talk Parseghian, who was only 51 when he left South Bend, would return to coaching, either in college or in the NFL, but he was finished—other than a 1976 cameo coaching the top collegians against the Super Bowl champion Pittsburgh Steelers in the final Chicago College All-Star Game. His final collegiate record was 170-58-6, and he was inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame in 1980.

Parseghian became a steady presence on television, first working at ABC with Keith Jackson from 1975 to ’81 and then at CBS from ’82 to ’88. Away from football, in ’94 he started the Ara Parseghian Medical Research Foundation, which seeks a cure for Niemann-Pick disease Type C, a genetic disorder that affects children, causing a buildup of cholesterol in cells that damages the nervous system. Three of his grandchildren, Michael, Marcia and Christa Parseghian, died from the disease.

Ara Parseghian knew what was expected at Notre Dame. He liked to say, “Whether you like it or not, you’re a national figure after five games at Notre Dame.” He never pulled the Lou Holtz tactic of making every opponent sound as fearsome as the Chuck Noll Steelers. He seldom gloated in victory or made excuses in defeat. But as much as any coach in Notre Dame history, Parseghian truly “woke up the echoes” and “shook down the thunder.”