Miami Is Once Again Good Enough to Ask a Program-Defining Question: Is The U Back?

CORAL GABLES, Fla. — You cannot pass through Miami’s football headquarters without being reminded of what the Hurricanes used to be. A mural bearing rows of former Miami players in NFL uniforms adorns a wall a few steps from the entrance to head coach Mark Richt’s office. Likenesses of past program greats in Miami threads, set against slick backgrounds with the famous orange-and-green U logo, line the hallways. Then there’s the Edgerrin James Team Meeting Room, the Edward Reed Recruiting Offices, the Clinton Portis Wing, rectangular plaques with recaps of Miami’s postseason results dating to before World War II, a trophy showroom and, atop a wall inside the Jonathan P. Vilma Football Players Lounge, a chrome banner listing the Hurricanes’ number of national titles (five), All-Americas (72), national award winners (20) and bowl appearances (40).

That is a partial list. Miami has seemingly developed more ways to package and promote its rich history than it has developed draft picks (336), but it is not stuck in the past. It would be more accurate to say that the Hurricanes are on a quest to regain what made all of those accolades possible to begin with: the ability to consistently compete for championships with star players.

Miami’s September schedule hardly followed script, but it also did nothing to sidetrack the high expectations that accompanied the start of Richt’s second season in Coral Gables.Media members picked the Hurricanes to win the ACC Coastal, even though the program has never finished atop the division since joining the conference in ‘04. They beat FCS foe Bethune-Cookman 41–13 in Week 1, saw two weeks of their schedule washed out by Hurricane Irma and then dispatched MAC power Toledo and an undefeated Duke team by 22 and 25 points, respectively, setting up a highly anticipated showdown with Florida State in Tallahassee on Saturday. Add that 3–0 start on top of Miami’s impressive close to the end of last season—a five-game winning streak capped by a 31–14 win over then No. 16 West Virginia in the Russell Athletic Bowl—and the recruiting momentum Richt and his staff have built, and a familiar question comes to the forefront: Is The U back?

What is that question really asking? Is it even possible to answer it? Some would prefer to hold off before rendering a verdict. “We’ll see around December time what Miami Hurricane football is about,” says junior running back Mark Walton. For others, it may be a moot point. “I’d say The U never left,” athletic director Blake James says. Being “back” may mean different things to different people with different perspectives on the program, but whatever the proper definition, it’s clear Miami is making progress toward recapturing the magic that made those championship teams the subject of nationwide fascination.

The first step was to fire former head coach Al Golden in the middle of the 2015 season, one day after suffering a 58–0 home loss to Clemson, the most lopsided loss in program history. To replace him, the Hurricanes reached way back into their past, to a reserve quarterback who played his final season in Coral Gables in ’82, the year before Miami’s first national title run.

When Georgia dismissed Mark Richt in November 2015, he says he thought about taking a year to “regroup and then decide for sure if this is what I want to continue to do.” But when the Hurricanes came calling, Richt knew that “the Miami job wasn’t going to be open a year later.” Although he says it “didn’t hurt” that Miami is his alma mater, Richt was attracted to the Hurricanes because of their track record of and commitment to success on the field. “I wanted to go to a place where football was important and where we could win,” he says.

Pundits and former Miami players lauded the hire, yet in some ways, the decision to bring in Richt ran counter to what made Miami, Miami. At their peak the Hurricanes had won three national championships over a five-year span; now they had hired a coach with an entrenched reputation for coming close but ultimately failing to lead his teams to titles. By the end of Richt’s run at Georgia, Bulldogs fans had grown weary of their program’s high-profile flops under the charge of the man that Rolling Stone described in September ’14 as “College Football’s Charlie Brown.” If Miami wanted to break back into college football’s elite tier, why would it hire a coach who repeatedly failed to get there over the course of 15 seasons?

Richt wants to win, but he wants to do it in what he calls a “first-class manner.” At Georgia he distinguished himself from his SEC head coaching peers by fostering a straight-edge culture that left little room for off-field shenanigans. As Aaron Murray, a former Georgia quarterback and current CBS Sports Network analyst, put it recently, “He wasn’t the type of coach that said, ‘Hey you’re going to get three, four chances to get in trouble and we’ll just give you a little slap on the wrist.’ ”

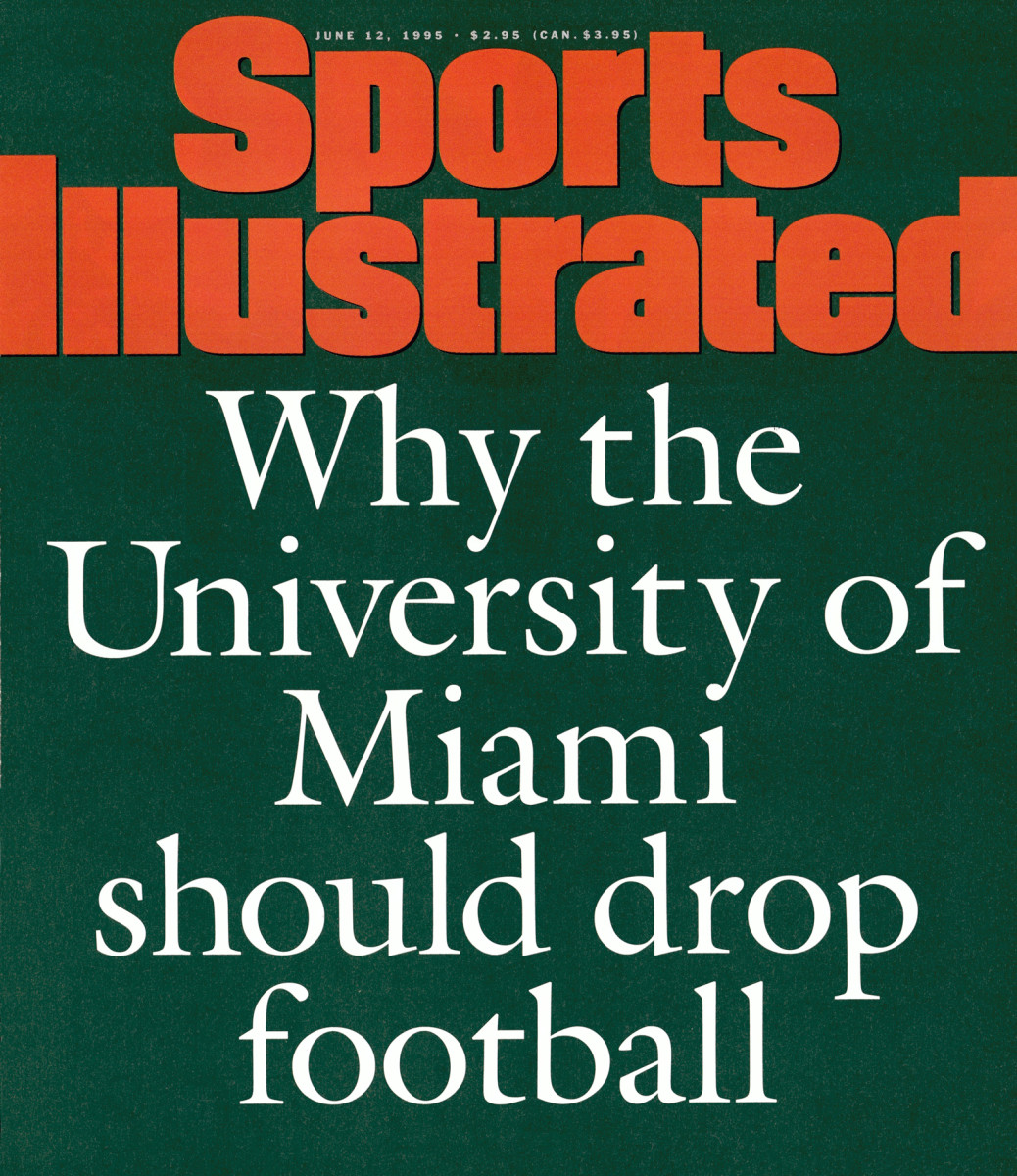

By contrast, Miami’s manner of winning chafed at people around the sport, and the program endured withering criticism over its rampant rule-breaking. The NCAA instituted legislation, later dubbed the “Miami Rule,” to rein in taunting after the Hurricanes incurred 202 penalty yards in a 46–3 win over Texas in the 1991 Cotton Bowl, and the program’s image had taken such a beating by the middle of the decade, after revelations of widespread misconduct, that this magazine called for the university to drop football. It repeated the claim 16 years later, following a Yahoo! Sports report detailing allegations of NCAA violations involving mega-booster Nevin Shapiro.

Richt inherited a talented roster, even if it wasn’t one equipped right away to meet the ambitions of Hurricanes fans. Its most impressive feature was a front seven that last season included three true freshmen starters at linebacker (Michael Pinckney, Shaquille Quarterman and Zach McCloud) and a defensive end, Joe Jackson, who led all ACC freshmen with 0.89 tackles for loss per game and bested all other Miami players with 11.5 tackles for loss and 8.5 sacks.

Defensive coordinator Manny Diaz unleashed that group to devastating effect in what he describes as an “attack-style 4–3” scheme. Miami wreaked havoc at the line of scrimmage and made life miserable for opposing quarterbacks, raising its national defensive ranking to 13th in 2016 from 52nd in ’15, according to Football Outsiders’ S&P + statistic. The Hurricanes’ stingy D helped them rebound from a winless October to rip off a five-game winning streak and reach 20th in the AP Top 25 Poll, their highest finish since ’09 (19th). Still, Diaz felt like there were ways in which his unit was “just kind of out there surviving.”

“[We are] trying to get deeper into the details of our defense and understanding why things happened,” Diaz says. “Not just, ‘Where am I supposed to be?’ but, ‘Why am I supposed to be there?’”

The program seemed to be ahead of schedule in Richt’s first season, though players were not satisfied with what they accomplished as much as they were encouraged by it. Today’s Hurricanes want nothing less than to match the great Hurricanes of yore. “The way we look at it is, they set the standard,” senior offensive lineman Kc McDermott says. “If we play below that standard, we’re not good enough.” Adds Walton, “We talk about it a lot. As players, you’ve got to want to speak that into existence.”

Quarterman, for instance, lost 15 pounds this offseason thanks to a stricter diet and has taken to heart a piece of advice three-time Pro Bowl linebacker Jon Beason gave him. “He said that there should never be a time that a Miami Hurricane linebacker is not in the camera screen on film,” Quarterman says. He’s shooting for All-America honors in ’17 after feeling like it was “kinda easy” to earn the freshman version of the honor because of the relatively small pool of players from which to choose.

Quarterman is a stud with an easy confidence and a bright future, but he’s only one name on a talented Hurricanes two-deep. Walton rated out as the ACC’s best running back not named Dalvin Cook last season by recording 1,117 rushing yards and leads the conference with 9.2 yards per carry through five weeks. After breaking Michael Irvin’s school freshman receiving record a year ago, sophomore wideout Ahmmon Richards returned from a hamstring injury last week against Duke and finished with three catches for 106 yards and a touchdown in his season debut.

Quarterback Brad Kaaya’s decision to leave school for the NFL was thought to have limited Miami’s ceiling in the playoff race, but junior Malik Rosier sits first in the ACC and 12th nationally in passer rating entering Week 6, and there’s more good news on the way at that position: The Hurricanes signed one of the top dual-threat signal-callers in the class of 2017, Vanguard (Fla.) High product N’Kosi Perry, who almost beat Rosier out for the starting job in fall camp. “We’re getting there,” Richt says. “I’m not going to say great things can’t happen now.”

The foundation of Richt’s plan to lift the Hurricanes to the Power 5 mountaintop is a variation of a proven Miami formula. He’s taking Howard Schnellenberger’s State of Miami recruiting blueprint, which focused on players south of Interstate 4 connecting Tampa and Daytona Beach, and condensing it to three counties: Broward, Miami-Dade and Palm Beach. Miami views those three counties, according to Richt, as a “state unto itself,” and assistants are assigned areas within them: three in Broward, three in Miami-Dade and two in Palm Beach. The tri-county area is brimming with high-end prospects, particularly at the skill positions. “We’re not going to advance from those three counties unless we can’t find exactly what we’re looking for,” says Matt Doherty, Miami’s director of player personnel. Half of the Hurricanes’ 24 class of ’17 signees and 10 of their 19 class of ’18 commits hail from the tri-county area.

Doherty stresses that Miami does not confine itself to that part of the state or country. The Hurricanes want elite talent, no matter where it comes from—four of the starting quarterbacks on their five championship teams (Bernie Kosar, ’83; Steve Walsh, ’87; Gino Torretta, ’91; and Ken Dorsey, ’01) played high school football outside of Florida. The Hurricanes currently hold a commitment from Bishop Gorman (Nev.) High’s Brevin Jordan, the No. 3 tight end in the class of ’18, according to the 247Sports Composite, and the most highly ranked signee in their ’17 class, four-star wide receiver Jeff Thomas, is from East. St. Louis Senior High in Illinois.

Keeping South Florida’s best high school players home may be more difficult today than it was during Miami’s stretch of dominance before the turn of the century. Programs from across the country scour the area for prospects, and unlike Miami, heavyweights like Alabama and Ohio State can sell recent conference titles and playoff berths. Chris Merritt, who’s in his 17th year as the head coach at Christopher Columbus High School in Miami, pointed out that it’s tougher to capitalize on local players flying under the radar. “There’s no secrets anymore,” Merritt says.

Still, the Hurricanes will always have home field advantage for nearby recruits, and the program carries a certain cachet in the eyes of many players even though they were toddlers the last time Miami won more than nine games in a season (11 in ’03). “That’s what we’re trying to do—bring the old U back,” says Gilbert Frierson, a four-star class of ’18 defensive back committed to the Hurricanes. A pair of ESPN 30 for 30 documentaries, titled The U and The U Part 2, have helped keep the program in the national college football consciousness, and Doherty considers them “instrumental” in Miami’s recruiting pitch. “The U,” says Lorenzo Lingard, a five-star class of ’18 running back committed to the Hurricanes. “is always on ESPN.”

And if watching footage of old Miami teams isn’t convincing enough, there’s evidence every fall Sunday afternoon of the number of stars the program has recruited and developed. Forty-two former Hurricanes made NFL rosters ahead of Week 1. “The kids identified that it was a down time and down period where UM was just not where it normally is,” says Tim Neal, the head coach at Coral Gables Senior High.

Under Richt Miami has enhanced its local recruiting presence by building strong relationships with coaches, offering to help with on-field tactics and inviting former Hurricanes to a popular summer event, the Paradise Camp, which is famously highlighted by Richt backflipping into a pool from a high dive. (This year’s attendee list included Irvin, Vilma, Ed Reed, Jeremy Shockey, Devin Hester and Vince Wilfork). The Hurricanes’ ’17 recruiting class ranked 12th in the country, according to the 247Sports Composite, and their ’18 haul currently checks in fourth nationally.

The tradition continues in paradise. pic.twitter.com/clbSdoVm4L

— Miami Hurricanes Football (@CanesFootball) July 22, 2017

Miami’s upward trajectory on the field has generated momentum off it. The university broke ground in May on a $34 million, 81,800-square-foot indoor practice building—to which Richt is donating $1 million—that lacks the slide and miniature golf course Clemson installed in its new facility but will include two turf fields, meeting rooms and a video center. “It keeps us on par with what’s out there,” James says. According to figures provided by Miami, the university’s Hurricane Club booster program raised $49 million in cash and commitments in the 2016-17 year, a $28 million increase over 2015-16, and season tickets jumped 39%, to more than 42,000, for the ’16 season. The Hurricanes can’t recreate the quaint charm of the old Orange Bowl, but Hard Rock Stadium completed a $500 million renovation this offseason, including new giant HD screens and an open-air canopy over seats. And as Richt notes, a huge part of why the Orange Bowl retains a sort of mythical allure in the minds of longtime college football observers is within the present-day Hurricanes’ control: “They won a lot there.”

More generally, people close to the program project optimism when discussing where they think Miami is headed under Richt. Larry Blustein, who’s in his 47th year covering recruiting in South Florida, says Richt understood what it took to “get that heartbeat back,” and former NFL defensive back Patrick Surtain, the head coach of powerhouse American Heritage High in Plantation, Fla., says he thinks Richt is “doing a terrific job” at restoring “that Miami brand.” Torretta acknowledged that a new coach “can’t make a team talented and have depth instantaneously” but says he believes Richt is “on the right track.” Dennis Erickson, the Hurricanes’ head coach from 1989 to ’94, says he thinks Richt is “going to get Miami to where they’re competing for national championships,” while Schnellenberger, who coached Richt at Miami before guiding the program to its first title in ’83, says Richt “knows exactly what to do” to win big with the Hurricanes. Bobby Bowden, under whom Richt coached for 15 years at Florida State, thinks the Seminoles are “just a step ahead” of the two other Power 5 programs in the state of Florida (Miami and Florida), but says Richt has “enough experience now, with what he gained at Georgia, to be one of the best coaches in the country.”

For some, Miami may not return to its previous heights until it regains a certain edge that once made it such a fearsome opponent—an aura that ESPN college football analyst Rod Gilmore describes as “kind of a unique style and swagger about them.” “They need to embrace the swag,” says Luther Campbell, a longtime Miami super-fan and the former frontman of rap group 2 Live Crew. But that won’t happen without better results on the field. The mentality Miami played with during its dynastic run reflected players’ confidence that they could whip the guys standing across the line of scrimmage. “The only thing that’s important is winning,” says Vilma, the leading tackler on Miami’s ’01 title team. “However Mark Richt wants to do it—I don’t care.”

By that measure, the answer to the weighty question—Is The U back?—does not have a clear answer. Not yet, at least. Defending national champion Clemson is still the class of the ACC and is viewed as stronger playoff contender than Miami through one month. The Hurricanes’ schedule softens up after the trip to Tallahassee—they have at least a 63% chance to win each of their remaining games, according to Football Study Hall—but a trip to the national semifinals may be a year or more away. For at least one Miami player, though, there is no doubt about the state of the program. “Is The U back? I believe so,” Quarterman said about a week before the Hurricanes’ season-opener. After pausing for a beat to let his answer sink in, Quarterman smiled. “Do you think so?”