Adidas's Loyalty to Louisville Goes Beyond the Terms of Its Contract

Thursday, April 17, 2014, was a magnificent day for University of Louisville leadership and their partners at Adidas. Together, the school and the brand announced a five-year, $39 million extension of a contractual affiliation that would cement Louisville as a showcase “Adidas school.” The contract dictated that Cardinals teams, coaches, trainers, staff and—most importantly—players would wear Adidas everything. Uniforms. Sneakers. Game-day warm-ups. Basketball shooting shirts. Football player capes. Headwear. Jackets. If it could be worn, it would say Adidas.

The announcement fortified the perception that the Louisville athletic department had arrived. A year removed from the men’s basketball team winning the NCAA tournament, Louisville negotiated the second-largest university athletics branding deal the German-based apparel company had ever signed. (Only Adidas’s deal with perennial powerhouse Michigan was worth more.)

As part of the Louisville contract, Adidas agreed to enrich the school’s ledger and campus—there would be annual direct payments worth $1.5 million along with state-of-the-art equipment, video technology, coveted internships and numerous other benefits worth millions of dollars. Reputational gains by an Adidas association likely aided Louisville in critical other ways, including in recruiting both student-athletes and students and in raising money from alumni.

Athletic director Tom Jurich, who came to the school in 1997, told The Courier Journal, “When I first got here, nobody wanted to try to brand us.”

Times had changed.

But this celebrated transformation was offset by a less triumphant reality. For the previous four seasons, Louisville’s director of basketball operations, Andre McGee, had hired strippers and prostitutes to engage in sexual acts with recruits visiting campus and then-current players. McGee’s famously micromanaging boss, head coach Rick Pitino, denied any knowledge of McGee’s enterprise, soon short-handed “Strippergate.”

But the NCAA found Pitino and the program at fault. Louisville agreed to a “self-imposed” postseason ban in 2016. Then, in June 2017, the NCAA Committee on Infractions suspended Pitino for the first five ACC games as a response to his failure to take action in the escort scandal. In addition, the NCAA vacated up to 123 victories, placed the school on probation for four years and commanded Louisville to return its portion of conference revenue sharing.

One might imagine that an established apparel company like Adidas would have revisited its decision to associate with Louisville. “Strippergate” not only violated NCAA rules, but was, to traffic in understatement, deeply demeaning to women and deeply at odds with what has become this #MeToo cultural moment.

Besides, Adidas had not exhibited much patience with others paid to wear the three stripes, who then encountered trouble. For instance, the company had dropped its shoe deal with musician Teyana Taylor in December 2013 after she’d cursed at Rihanna on Twitter. And, six years prior, Adidas had cut ties with Washington Wizards guard Gilbert Arenas after he pleaded guilty to carrying a gun without a license.

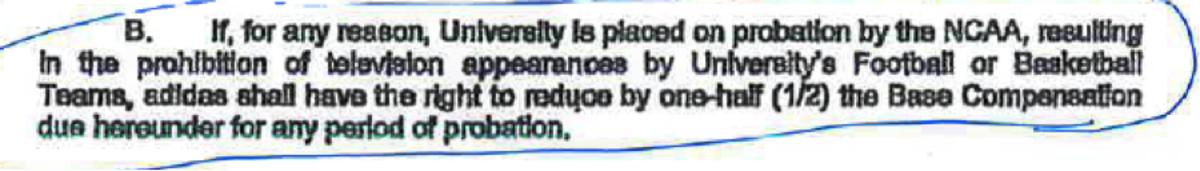

SI has obtained a copy of the contract between Adidas and Louisville. It's clear that Adidas was armed with the authority to modify or outright end its relationship with Louisville. Under paragraph 3.B, Adidas could have reduced its base compensation to Louisville by one half if the university was put on NCAA probation, resulting in loss of TV appearances by the football or basketball teams:

The base compensation ranged from roughly $1.5 to $1.6 million per year, meaning a reduction by one half would have translated into a reduction in payments by about $800,000 per year. In 2016, Louisville, in hopes of satisfying an outraged NCAA committee on infractions, banned itself from the ACC and NCAA tournaments. Sources familiar with the contractual relationship between Louisville and Adidas tell SI that Adidas may not attempt to interpret 3.B as justifying a contractual reduction.

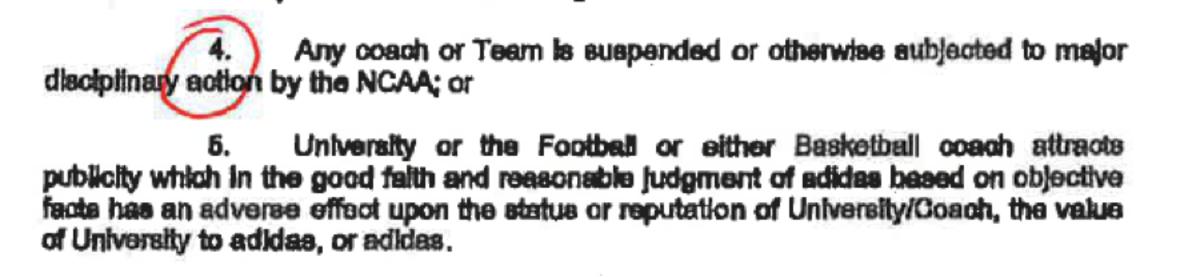

Alternatively, Adidas could have relied on paragraphs 12.4 and 12.5 to terminate the Louisville contract:

These paragraphs make clear that Adidas possessed the right to terminate the Louisville contract if the NCAA punishes the school or the coach, or if the school or coach merely generated adverse publicity. Clearly, the NCAA’s punishment of the school and Pitino—in addition to the ridicule and embarrassment caused by the sex scandal—would have empowered Adidas to cut ties with the embattled program. Was the termination clause not included in the contract for precisely this kind of embarrassing scandal?

Adidas did revisit its association with Louisville following Strippergate. But not in a way that logic might predict. Instead of attempting to suspend, reduce or even terminate the agreement, on August 2017, just two months after the NCAA punished the school and coach, Adidas and Louisville negotiated a massive 10-year, $160 million contract extension, the largest such sponsorship in the company’s history. The extension—which goes into effect on July 1 of this year and runs to 2028— was celebrated with a pep rally in Papa John’s Cardinal Stadium.

The Cards became recipients of the fourth-richest branding deal in college sports. Chris McGuire, the senior director of sports marketing for Adidas North America, didn’t seem particularly disturbed by Louisville’s off-court issues, telling The Courier Journal, “We’re proud this will be our largest commitment in the college space.” According to ESPN, in internal strategy documents, Louisville vowed to “write the next chapter for college athletics, for streetwear and fashion.” Jurich, by this point earning in excess of $5 million put it this way: “We’re part of the Adidas family, and I certainly hope they know they are part of the Cardinal family.”

The extension dramatically increased the amounts and ways in which Adidas will pay Louisville. This year, for example, the annual base compensation surges from $1.6 million to $10 million. The deal added jobs to Louisville’s athletic department, including the hiring of Jurich’s daughter, Haley, to serve as a liaison between the school and Adidas.

Then there is this: in addition to the base, according to the extension, Adidas will pay Louisville $3 million annually in what are vaguely referred to as “activation investments.” The monetary value of these “activations” far eclipses those contained in the 2014 deal, which annually netted Adidas a comparatively modest $440,000 to $530,000.

So what are these so-called “activations”? That remains a bit of a mystery in the Louisville deal. Activations fall under the broad umbrella of “marketing.” The contract explains that “activations” include a diverse alliance of “University/Adidas internship program, agencies and Adidas strategic brand initiatives.” The contract foregoes further detail and explanation.

Louisville spokespersons have offered additional commentaries on activations. In 2014, Brent Seebohm referred to activations as “extra marketing” value for Louisville. On March 15, Kenny Klein told SI via email that activations are geared for “co-promoting both brands in a mutually beneficial manner” and cover such items as the aforementioned internship program, co-branded facility signage/upgrades, brand campaigns, associated media buys and “special programming initiatives such as partnering with their Brooklyn Farm to research next gen design and market creative.”

That Adidas would spend on promoting its sponsorship with Louisville is hardly surprising. Activation fees are not uncommon in sponsorship deals and typically refer to payment arrangements for marketing efforts to promote a sponsorship. Money spent by sponsors on activations is in addition to money spent to secure the sponsorship rights.

Yet the open-endedness and stunningly high dollar amounts paid to Louisville to promote the Adidas sponsorship invite scrutiny. This is particularly true in the middle of a college basketball corruption scandal that has implicated Louisville and featured under-the-table payments transmitted under the guise of legitimacy.

Activation investments are also not boilerplate clauses in Adidas deals. SI is in possession of the branding contracts Adidas negotiated with Indiana University athletics back in 2016. They do not contain any activations. Such fees are also not found in branding contracts signed by other major apparel companies. SI has obtained branding contracts negotiated by Nike with the athletic departments of the University of Kentucky, the University of Oregon and the University of Minnesota. A review of these contracts reveals no activation investments either.

Sources tell SI that the Adidas contract for Houston Rockets star James Harden—worth even more than Louisville—contains no activation clauses. (Asked to comment on the Louisville contract generally and the activation fees in particular, Adidas declined.)

The Adidas celebration at Louisville ended abruptly. Only a month after the deal, the college basketball corruption charges became public. Louisville and Adidas now play starring roles in a Department of Justice production, equal parts taut thriller and whodunit centering on alleged widespread and systematic bribing of basketball recruits. Although Pitino’s name does not appear in government indictments, he is described as collaborating with Adidas director of global marketing James Gatto, Adidas basketball organizer Merl Code and investment advisor Christian Dawkins in funneling payments totaling $100,000 to the family of Brian Bowen, a five-star recruit who committed to Louisville.

These payments, the Justice Department contends, were illegal bribes and use of the postal system and wires to carry out the bribes constituted fraud. Louisville would eventually fire Pitino and Jurich—two figures essential to the decision of Adidas to enrich Louisville.

Pitino’s alleged actions alone could justify Adidas terminating its contract with the school—the company did terminate its personal services contract with Pitino after he was dismissed. Last October, Louisville took the step of firing Pitino “for cause,” meaning without pay and on the grounds that Pitino violated contractual provisions that require compliance with law, NCAA rules and basic ethics (Pitino has sued the school and Adidas in response to his firing). Based on the school’s own conclusions against Pitino, Adidas could have easily invoked paragraphs 12.4 and 12.5. To that end, Adidas could have logically reasoned that Pitino had “attracted publicity” that had an “adverse effect upon the status or reputation” of Pitino, Louisville and Adidas.

Adidas would have still other grounds to invoke 12.4 and 12.5. Pitino, Louisville asserts, violated his contract by neglecting to inform university compliance officers that Dawkins was on campus. Even if Pitino had not been implicated further, he would have brought about unflattering and adverse publicity on himself and school by not protecting his school from association with an alleged briber.

One possible reason for Adidas’s reticence in invoking the termination clause: The company itself is implicated in some of these controversies. If the company concluded that it was “in too deep” with Louisville, then strategically, it may have made sense to continue the relationship.

Yet now, Adidas might regret such a choice. Gatto and Code are charged with felonies, and it stands to reason that the FBI has demanded from Adidas that it turn over emails and other records. Plus, should the college basketball corruption cases go to trial, Adidas North America CEO Mark King and McGuire, the executives who signed the Adidas Louisville $160 million extension, will likely be deposed and called as witnesses.

This all could trigger an activation of something far more severe than an apparel sponsorship.