The Blessing and the Curse of Being Lane Kiffin

Start a free seven-day trial of SI TV today to see Andy Staples’s full 30-minute interview with FAU’s polarizing head coach, along with other in-depth interviews and features on the biggest names in sports.

BOCA RATON, Fla. — In the pantheon of Text Messages I Never Saw Coming, this one from a few Sundays ago might have surpassed the time Miss Sweden invited me to meet her at a bar*.

Lane Kiffin: If u want a church to go to there is a ten am on campus I take the players to

I look at the screen, look away and look again. Still the same. Lane Kiffin has just invited me to church.

Cynical is my baseline, so this sets off multiple alarms. Does he think this is going to be one of those stories about how he’s found the Lord and changed everything about his life? Is he trying to scrub a reputation earned tweet by tweet and whispered story by whispered story? I can’t help but wonder why, but I also have to go. How often, after all, does Lane Kiffin invite you to church?

So I drive to Florida Atlantic’s campus. Victory Church began renting out the university’s performing arts center in 2017 after outgrowing its previous digs; the football team is 10–0 since the move. Victory is one of those come-as-you-are, non-denominational Christian churches where the pastor sounds like he also runs a coffee shop and everyone involved in the service has an untucked shirt. At the allotted hour, the band cranks up. I haven’t listened to much Christian rock since Stryper’s To Hell With The Devil charted, but this particular band slaps. In front of the drum kit, a group of young men and women alternate between leaping and singing.

In the quickly filling center section, about half the people rise and begin to sway. About a quarter of those people raise their hands, filled with the Holy Spirit courtesy of approachable power pop. In the stage-left mezzanine area reserved for the FAU football team, there is no sign of Kiffin. Another text informs me that he has just pulled into the parking lot. At this point, I make an executive decision.

If Lane Kiffin starts singing, I’m out of here.

*The Miss Sweden story is 100% true. This particular Miss Sweden won in 1978. Her name is Cecilia Rodhe, and she is an artist and the mother of Joakim Noah. In 2006, I was writing a story for The Tampa Tribune on the mothers of Florida basketball players Noah, Al Horford and Taurean Green—all of whom had pro athlete fathers but whose mothers had done most of the heavy lifting raising them. Rodhe had a great photo of herself and a younger Noah on her phone that she hoped we could include with the story. But in ’06, no one older than 21 knew how to get a photo off one person’s phone and into someone else’s computer. So she asked me to meet her at a bar in Minneapolis so one of Noah’s friends could transfer the photo.

Kiffin arrives wearing a T-shirt, shorts and flip-flops. He does not sing. He does not wave his hands. He visits with the three dozen or so players and coaches who have come this particular Sunday. Quarterback Chris Robison’s mom is visiting from Texas. Kiffin says hello. Offensive coordinator Charlie Weis Jr., 25, is here with his wife. Kiffin makes small talk. Church isn’t mandatory for the players or coaches, but Kiffin would love to see attendance like the Owls had the previous week, when the sermon had come from someone closer to the players’ age and a good portion of the team had filled that reserved section. Visiting pastor Gregg Tipton, who played quarterback at Hawaii in the mid-’80s before starting his own campus ministry program, delivers the sermon on this day.

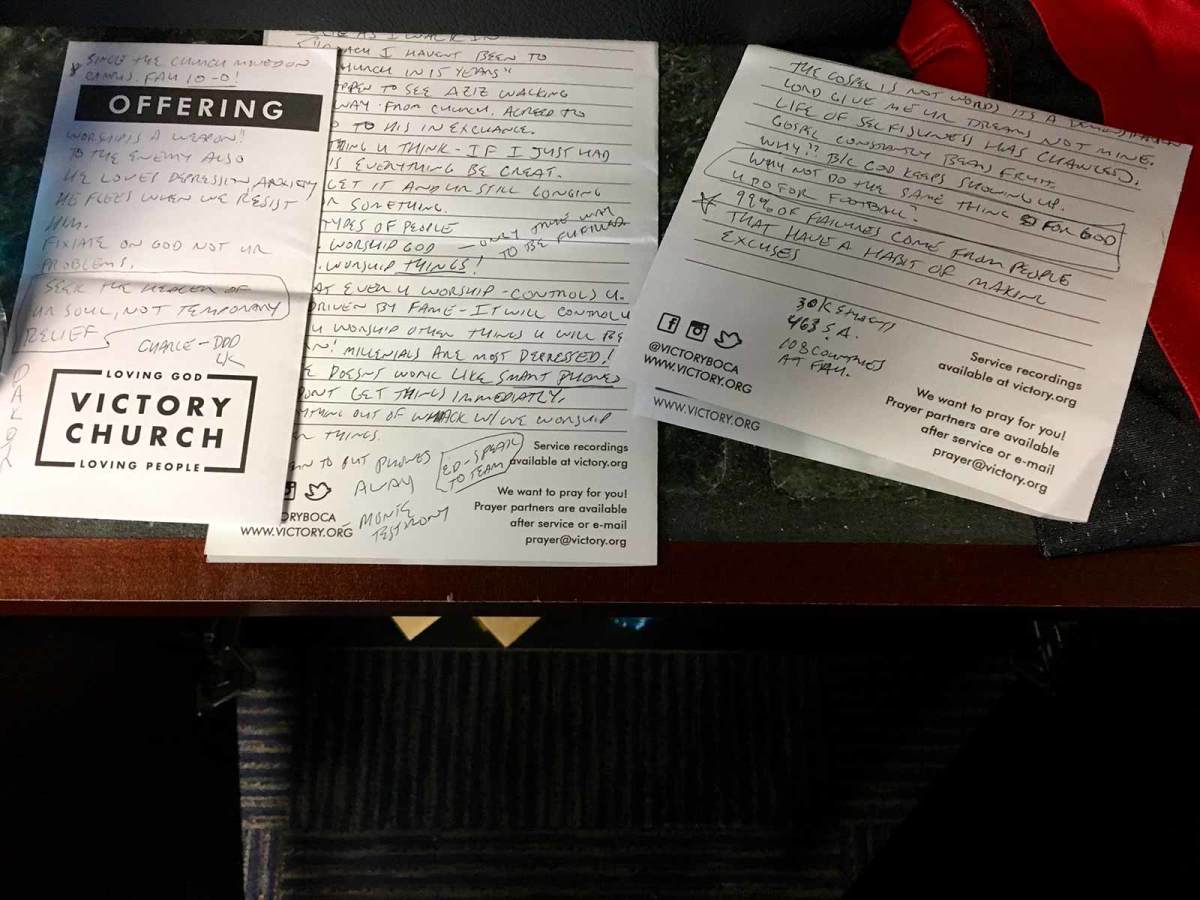

Kiffin spends most of the service jotting down notes. When Tipton flashes a George Washington Carver quote on the screen—“Ninety-nine percent of failures come from people who have a habit of making excuses”—Kiffin writes it on his notepad. As the band plays, Kiffin jokes that he never could have worn flip-flops to church when he served as Alabama’s offensive coordinator. He also says he would have needed an hour to get from the church to the parking lot. That won’t happen at FAU. “Just watch,” he says. “Not one person will ask for a picture.”

Outside, Kiffin gets recognized but not stopped. Later that Sunday, we’ll sit down for a more formal interview about Kiffin’s journey from twice-fired head coach to resurrector of a program that had gone 3–9 the year before he took it over and went 11–3. (You can watch the interview in its entirety on SI TV, and I suggest you do because Kiffin’s answers on everything from Twitter to program culture to the differences in offensive scheme between college and the NFL are fascinating.) After Kiffin answers the last question, we say our goodbyes. But before I can get too far north on Interstate 95, I get another text.

It’s from Kiffin. He’s concerned about how I’ll chronicle the church visit. He wasn’t trying to spin me, he says. He doesn’t want anyone to think he’d use the church as a prop. He sends a photo of his notes from the sermon to help prove his case.

Kiffin doesn’t need to argue that case. Had he sat in the front row or tried to fake his way through a Biblical discussion, this would have been an entirely different story, and he would have been the villain. Kiffin invited me to church on that Sunday because that’s what he and some of his coaches and players do. It’s a wholesome picture of the program that certainly will play well with recruits and their parents, but it’s also something that actually happens in Kiffin’s program. It’s something Kiffin should want people to know about, but because he understands better than most how people today react to what they read and see and hear—especially when it comes from him—he’s already dreading the backlash.

This is the blessing and the curse of being Lane Kiffin. No matter what he does, people will pay attention. But there’s a good chance many of those people will get mad.

For some reason, nearly everything Kiffin does draws an outsized response. We could write a feature about Purdue’s Jeff Brohm or Boise State’s Bryan Harsin or Iowa State’s Matt Campbell, but those wouldn’t draw nearly the traffic that this one will. Arkansas coach Chad Morris can send a tweet, but it won’t draw the retweets, the likes or the responses that a tweet from Kiffin will. For his part, Kiffin isn’t sure why attaching his name to anything drives up the engagement rate. “I always want to ask you guys that question, because I do not understand exactly why that is,” he says. “It’s crazy.”

Perhaps it’s because he rose so high, so fast, and then crashed so spectacularly. At a recent Monday practice, Kiffin chats with Weis about Black Monday. “You’re not really a coach until you’ve been through a Black Monday,” Kiffin says to the young coordinator. He’s referring to the day following the NFL’s final regular-season Sunday that usually features a spate of coach firings. Then Kiffin remembers he was fired by the Raiders (at age 33) following the fourth game of the 2008 season. He then points out that he was fired by USC (at age 38) following the Trojans’ fifth game of the ’13 season. “Let’s try to make it to Week 6 this year,” Kiffin cracks to Weis, who also is the son of a famous football coach.

Kiffin passed through what should be the entirety of the coaching life cycle before his 40th birthday. The son of legendary NFL defensive coordinator Monte Kiffin, Lane was named offensive coordinator at USC at age 29. His time running the offense of what was at the time college football’s most consistent program put him on a lot of radars.

He probably wasn’t ready in 2007 when he got offered the Oakland Raiders’ head coaching job, but was he supposed to turn it down? Kiffin fell out with legendary Raiders owner Al Davis, who while announcing Kiffin’s firing said, “I think he conned me like he conned all you people.” Davis accused Kiffin of lying, but he also got mad at Kiffin for complaining about the selection of quarterback JaMarcus Russell, which, in hindsight, seems like a plus in Kiffin’s column.

Kiffin then became the head coach Tennessee, where he clashed with Florida’s Urban Meyer—the coach of the defending national champ—and generally ran his mouth in ways that first-year SEC coaches are not supposed to run their mouths. Hostesses from his program showed up at a high school game in South Carolina. He had to boot some of his prized recruits because of their role in a robbery. Did we mention that Kiffin was only Tennessee’s coach for 13 months?

Some people rioted in Knoxville when Kiffin took the USC job in January 2010. Those same people laughed in September 2013 when then-USC athletic director Pat Haden fired Kiffin at LAX when the Trojans returned home from a loss at Arizona State.

In an interview earlier this year with a writer from AthletesForGod.com*, Kiffin called this moment his professional low point. “I don’t wish that feeling upon anyone,” Kiffin said. “I wanted to die, because at the time I was defined by my job.”

*The story is presented as an as-told-to, meaning it looks as if Kiffin wrote it. He insists he did not. He only answered interview questions and approved the final version. The attention this drew made him even more concerned that people would think he’s pushing a Born Again Lane narrative.

“[Die] wasn’t probably the right word,” Kiffin says when asked about the statement. “But it did feel like that. This is your dream job. You left a phenomenal job, a top-10 job at Tennessee for—what was for you—the No. 1 job.” If Kiffin has made a change, it’s this: He knows now that moment provided fuel he can use for the rest of his life. But it took time to realize that. “As painful as it was, that happening made me a better coach,” he says. “Whether I agree with it or not. It’s just like when we bench players. I don’t expect for them to agree with it.”

Kiffin still doesn’t agree with the USC firing. He believes the scholarship penalties the NCAA hit the Trojans with as a result of the Reggie Bush case hamstrung the program to the point that no one would have won enough games to satisfy the administration. But, as the quote he wrote down in church suggests, that’s an excuse. Kiffin admits he let his team buy too much into its preseason ranking in 2012 (No. 1) after going 10–2 in ’11. He didn’t manage expectations properly, and that 7–6 season paved the way for his downfall in Los Angeles.

One of Kiffin’s favorite books is Ego Is the Enemy, which was published in 2016 by author Ryan Holiday. Recently, Kiffin gave a copy to FAU tailback Devin “Motor” Singletary, who, after 32 rushing touchdowns in 2017, is getting pumped up by the world much the way Kiffin was as a young coach. Singletary, who said he hasn’t read the book yet, seems to understand even without the book what a younger Kiffin did not—that arrogance and self-confidence are two very different things. The latter is necessary, but the former can destroy. “I’m reading the book,” Kiffin says, “and I feel like I’m reading about myself.”

That’s because he was. Kiffin’s firing at USC opened the door for the period that rehabilitated his coaching career. Entering the 2014 season, Nick Saban needed someone to run the offense at Alabama. He reached out to Kiffin at a time when Kiffin’s phone wasn’t ringing. Kiffin would wind up staying in Tuscaloosa for three seasons, helping the Crimson Tide win three SEC titles and one national title. Kiffin now says he needed all three seasons, even if he might not have said it at the time. “I would have told you I was ready after one day,” he says. “But that’s the ego in me.” The truth is he needed to understand how Saban organized his program and how he made his players and coaches process-oriented rather than result-oriented. “You can’t just go visit somewhere and come away and know how they run their business,” Kiffin says. But after living in that organization for three seasons, Kiffin felt as if he understood it. (Even if ego struck near the end—after Kiffin had accepted the FAU job—and got Kiffin dumped between the 2016 Peach Bowl and the national title game.) That’s why he took the FAU job for about half what he could have made as LSU or Alabama’s offensive coordinator. He was ready to prove he had finally learned how to be an effective head coach.

Kiffin’s results at FAU are undeniable. The Owls won nine games in Charlie Partridge’s three seasons. They weren’t even a blip on the national radar. After starting last season 1–3, FAU reeled off 10 consecutive wins. The Owls haven’t trailed since the fourth quarter of a 42–28 win at Western Kentucky last Oct. 28. No matter what you believe about whether Kiffin has changed mentally since he was fired at USC, he absolutely has evolved schematically. Watching the Owls scrimmage earlier this month, they appear to be playing an entirely different sport on offense than Kiffin’s Trojans. Those USC teams huddled. Their quarterbacks played under center. They shifted tight ends from one side of the field to the other. Kiffin held a play sheet approximately the size of a Cheesecake Factory menu. Now? The Owls don’t huddle. They don’t have fullbacks. They run plays as quickly as possible. Kiffin’s play sheet is the size of a notebook page. “I’m proud of that,” Kiffin says of his offensive evolution. “That goes back to ego. It’s almost as if you can see it now when you see people where the ego is hurting them. They’re not going to change—whether it’s picking the starting quarterback or whether it’s an offensive system. They’re going to do it ’til they die—or until they get fired. That’s probably the thing I like the most. We do not look anything like we did before. And that’s because we’ve changed.”

Kiffin has gone young with his hires. You know about Weis. Strength coach Wilson Love, meanwhile, is 26. This is the first on-field FBS job for seven of Kiffin’s 10 assistants. That youth movement has encouraged evolution. It also has produced a culture that doesn’t tolerate coaches dog-cussing players at practice. Kiffin’s coaches yell, but they tend to focus their criticism on the task at hand. “If I’m cussing at you, swearing at you, calling you demeaning names, are you really thinking about that last play?” Kiffin asks. “Am I really helping you get better? Or am I just making myself feel good by demeaning you? I’ve really never understood it.”

Kiffin also has altered his program sales strategy. This aspect of his coaching style has always been fungible. He tried to be boring with the Raiders and with USC because neither organization needed to raise awareness. He tended toward outrageous statements at Tennessee because it got people talking about the Volunteers, who are at their best when they can recruit nationally. At FAU, Kiffin has taken that to a different level thanks to Twitter. He originally began using the service because the NCAA used to allow coaches to direct message recruits but not text them. (That rule has since changed.) At Alabama, Kiffin—who only spoke publicly a few times a year because of Saban’s One Voice policy—discovered he could make waves and have fun by tweeting. If he snapped a photo of the Tennessee license plate on his rental car while recruiting in the Volunteer State, he could rile those Tennessee fans still mad about the way he left. At FAU, Kiffin retweets a video of a bear riding in the back of a pickup truck, confirms that apartment dwellers who live across from Alabama’s practice fields sign forms saying they won’t watch the Tide practice and decries the “rat poison” (a Saban term) from anyone who predicts that FAU might beat Oklahoma this week or might lead the state of Florida in wins this season.

After last season, FAU president John Kelly told ESPN that applications to the school were up 35% year-over-year. “And we haven’t done anything else differently, so it has to be Lane,” Kelly told ESPN. “He just gets it, both as a football coach and being able to attract attention to our university. I laugh just about every day at something he puts on Twitter and understand that he’s about the good of the institution and is thinking about what appeals to a 17-year-old kid and not a 60-year-old guy.”

Kelly’s sentiments were not shared by most of the athletic directors Yahoo! Sports writer Pete Thamel interviewed for a recent story about Kiffin and other Group of Five head coaches who could soon ascend to the Power 5. Of the 15 Thamel interviewed—all were granted anonymity—11 said they wouldn’t hire Kiffin. “Not a chance,” one AD told Thamel. “Too much smoke/drama around him. And he’ll probably think he’s Vince Lombardi if he wins another season.”

It infuriates Kiffin that no one was willing to attach their name to those sentiments. But, as Kelly pointed out months before that story was written, Kiffin isn’t typing tweets or making decisions for those people. “Do I work for those 15 athletic directors? No,” Kiffin says. “Did they hire me? No. So am I supposed to be pleasing my athletic director and my president, or am I supposed to be pleasing other people’s so that I can potentially get a job at those places?”

Kiffin, who just received a 10-year extension at FAU (which comes with a very manageable buyout of $2 million should he be hired away after this season), isn’t worried about pleasing everyone. “Personally, I have hurt myself by doing that,” Kiffin says. “Because that hurts my image outside. People say ‘Why is he doing that on Twitter? Why is he doing that? Well, he’s doing that because it’s helping the school. It’s bringing more kids here. The recruits like it. The recruits’ parents like it. And our fan base likes it. Maybe someday you guys will get that.”

Here’s an alternate theory to Kiffin’s supposition that all this talking and tweeting has damaged his chances of getting another Power 5 job. Maybe these are features and not bugs. Maybe Kiffin is a better coach when he’s letting it rip on Twitter and trying to make his program as fun as possible. Remember, this is the guy who once banished cookies from USC’s training table. (Current LSU coach Ed Orgeron, who took over as the USC interim coach when Kiffin was fired, became a folk hero when he brought back those cookies.) That Lane Kiffin wasn’t a great coach at that level. Maybe this one could be. But it probably won’t work unless an athletic director is willing to loosen up and let Lane be Lane—ego and all. It definitely won’t work if, for some reason, Lane decides that he shouldn’t be Lane.

As he tries to improve upon his most successful season as a head coach, Kiffin no longer seems interested in doing what coaching convention says he should do. “Should we go back to huddling? Should we go back to putting all these tight ends in there and have 250 yards a game? It doesn’t win anymore,” he says. “So should we do it because that’s what the people before us did? No. So if we change in all these other areas, why are we as coaches not supposed to change on Twitter? Why are we not supposed to change how we are with the players or with the media?”

Shortly before the end of our interview, I show Kiffin the parody I made of his now-famous season-ticket drive video from January 2017.

Our first subscriber drive video was fine. But Lane Kiffin will tell you that synthesizers are required for optimum results. pic.twitter.com/6JPbNpw8z6

— Andy Staples (@Andy_Staples) January 31, 2017

He says I brought more energy than he did, but again he says we don’t get it. “That was on SportsCenter the next day,” he says. Kiffin insists the video was an intentional viral sensation. And maybe that’s exactly what happened. Maybe an act of boredom wasn’t retconned into an act of genius. Maybe he is playing chess while we satisfy ourselves with checkers.

And maybe I’m writing 3,400 words about Lane Kiffin—and 141 about Miss Sweden—so he’ll retweet the story…