In the Desert, Herm Edwards Makes One Last Stand

This story appears in the Sept. 24–Oct. 1, 2018, issue of Sports Illustrated. For more great storytelling and in-depth analysis, subscribe to the magazine—and get up to 94% off the cover price. Click here for more.

I have spent just shy of 90 minutes in Herm Edwards’s office in Tempe when the Sun Devils’ new coach deems me worthy of receiving a new Hermism. As I await the words, I notice that a small ceramic copy of the Ten Commandments sits on the end table next to my chair, and I begin to think that this is as close as a sportswriter can come in 2018 to Moses’s experience on Mount Sinai. (It must have been more temperate in Egypt. In Arizona at July’s end, it’s monsoon season, 106° and humid.)

Thus spoke Herm:

When you’re interested in something, you do it only when it’s convenient. When you’re committed to something, you accept no excuses, only results.

Leaning back in his armchair, with his feet up on the coffee table, Edwards explains that such maxims don’t come easily. “I’m a thinker, man! I come up with all of this myself. This is why I get up at 4:30 every morning,” Edwards says.

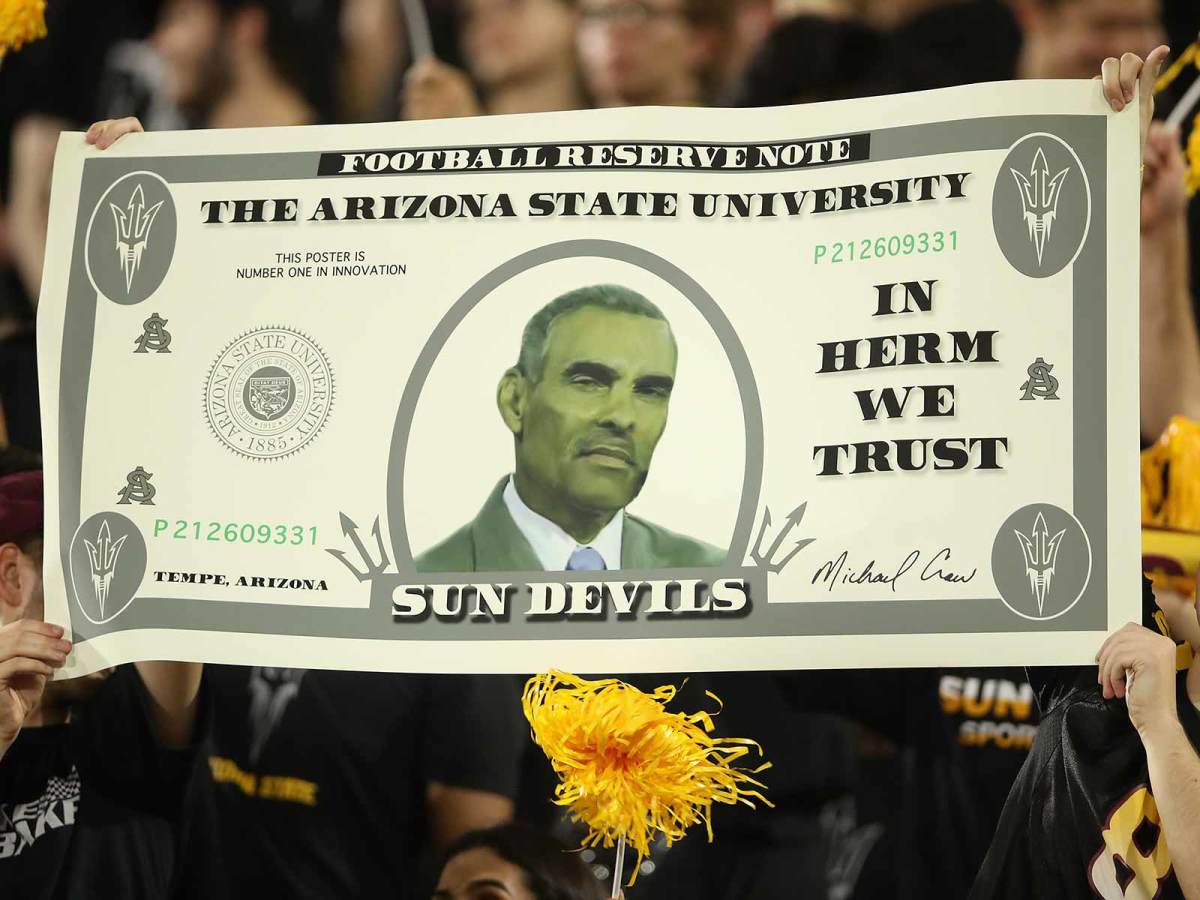

It doesn’t take much for a coach to become more meme than man. Ask Mike (“I’m a man! I’m 40!”) Gundy or Jim (“Playoffs?”) Mora. A couple of catchphrases, maybe an occasional press-conference meltdown, and soon a coach’s legend dwarfs his ledger. Herm Edwards, having traded his boxy TV-analyst suits for polos with pitchforks on them, is here to say that it gets better. There is life after memehood.

Before September rolled around and his Sun Devils vaulted into the Top 25, Edwards had last coached a game that counted in 2008. His final two seasons in Kansas City, his teams were 6–26. He needed some time away to recharge. He spent just a week out of work before ESPN snapped him up to join the cast of NFL Live. Surely the coach behind the epochal 2002 “You play to win the game!” rant could hold his own on TV, and did he ever. Was there any assignment he couldn’t handle? He did a bit where he appeared in a leather jacket and dark glasses as the Herminator. In another bit, he held up a smartphone and implored athletes, “Don’t press send!” He once delivered speeches to the camera as though he were coaching specific teams—he dressed up like Bill Belichick, hoodie and all. Herm was a ham.

For nearly nine years ESPN called upon him to be its all-purpose coach and moral compass. He says he passed up “more than five” head coaching offers—college and pro—in his time in Bristol, Conn. Then a call came in from ASU, where his old agent, Ray Anderson, was the athletic director. They needed a coach who could jump-start the program by landing recruits that for years had been going to USC, Stanford, UCLA, Oregon and Washington. They needed someone who could, in college football argot, win the living room. Who better than the man who had been beamed into millions of living rooms for almost a decade?

“People who’ve watched me on television, they go, ‘Oh, that’s who this guy is.’ So when I walk into their home, they say, ‘Coach, you’re that same guy! We trust you with our son.’”

Is it really that straightforward? In his first abbreviated crack at recruiting—Edwards was named coach last December—he did indeed land a reasonable haul of prospects, vaulting the Sun Devils’ incoming class, by one expert’s reckoning, from last in the Pac-12 to fifth.

What’s for sure is that Herm Edwards is that same guy. In person, as on television, the man is more sonically dynamic than Mahler’s Third Symphony. TV producers often say to be yourself, but half as much; if Edwards were even a percentage point more himself than he usually is, he’d have an aneurysm. He tempers his piercing tenor and still-sinewy physique—the hallmarks of a drill sergeant (Herman Edwards Sr., who died when Herm was in college, was a master sergeant in the U.S. Army)—with a playful manner and frequent cackles. After all, how nasty a figure can a man cut when the radio in his office is tuned to Watercolors, SiriusXM’s smooth-jazz station, all day, every day?

He resents the notion that time he spent on TV was unproductive. “I almost chuckle when people say that,” he says. “Just because you’re absent from the playing field, you don’t stop coaching. I coached every day when I went to work. I was coaching America!”

Clay Helton Still Has Time to Avoid Becoming a Victim of USC's Recent Success

Few head coaching hires in recent history have been as assailed as the Sun Devils’ decision to replace Todd Graham, who had been in Tempe for six years, with Edwards. It wasn’t just the nine seasons since his last coaching job, or the fact that he had never run a college team. It was also that the 64-year-old Edwards would be the third-oldest Power 5 head coach, behind Bill Snyder and Nick Saban. (Arizona State, he insists, will be his last coaching job.) It was also that the affinity he displayed in the NFL for a run-heavy offense and a Cover 2 defense made him seem behind the times a decade ago.

It was also that fans of the Jets and the Chiefs could still recall the moments when Edwards seemed to discard basic tenets of clock and game management. It didn’t help that Arizona State bungled the rollout every which way. Edwards’s current agent, Phil de Picciotto, was given a speaking slot at his introductory press conference. ASU announced after his hiring that both coordinators were staying on, and then both were gone within a week. The fan base liked Graham generally but didn’t mind seeing him go; they did mind replacing him with a TV talking head.

“I guess I should have been a little more attentive to the fact that some of our fan base might be a little taken aback because Herman was such an ‘out of the box’ candidate,” Anderson says. “I suspected that some of the millennial media members, who didn’t have a full knowledge of who he was, might recoil and declare it crazy.”

Says Edwards, “The guy who hired me felt I was the right guy. Fans have their own idea about who to hire; that’s what makes football great. I’ve been in this game too long to care.”

The case for hiring Edwards was hardly more complex than a halfback dive. ASU hasn’t finished in the top 10 since 1996. The Sun Devils followed 10‑win seasons in 2013 and ’14 with six-, five- and seven-win seasons in ’15, ’16 and ’17, respectively. Since 2013, only three ASU players have been drafted in the first three rounds. And with ASU’s new $300 million football facility and its renovation of Sun Devil Stadium set to finish in ’19, it didn’t make sense to hire a coach who would need three or four years to make a dent with recruits.

“Just look around our conference,” says Anderson. “The college game is about recruiting. And I knew that Herman could recruit.”

Edwards added veteran scout Al Luginbill, with whom he had worked on the Under Armour All-America game, as director of player personnel, and he beefed up the scouting department. They have color grades for every prospect and targets they want to hit in terms of height and weight at every position. “We’ve set it up just like a pro team,” Edwards says.

Edwards is especially enthusiastic (which is saying something) about a new wrinkle in his recruiting strategy. He leans in close to talk about it: “You’ve got, let’s say, 25 scholarships you can give out every year. My opinion, you don’t give all 25 out every year. You save two! ’Cause some guy’s coming free. The rules now, if you don’t like it as a player, you ask for your release. If you’ve got a scholarship open, and you’re one of the schools they’re interested in—you’ve got a guy!

“Our left tackle, Casey Tucker, Stanford, graduated, had another year left, got hurt early, didn’t play a lot his senior year. Vocal guy. Guess what? We got him. Our left guard, from USC. We got him. You gotta realize, in the grand scheme of it, I’m gonna hold two spots. Let’s just say a quarterback comes available . . . if you’ve got a scholarship to offer him, and he likes your program, guess what—you’ve got a guy!”

How North Texas and Its Firefighting Walk-On Stunned Arkansas With the Trick Play of the Year

Tucker and that guard from USC (Roy Hemsley) joined an offense with some depth: the Sun Devils’ receiver tandem of N’Keal Harry and Kyle Williams combined last season for 15 touchdowns and nearly 2,000 yards. Senior quarterback Manny Wilkins is in his third year as the starter, and sophomore running back Eno Benjamin, starting for the first time, had been ranked sixth nationwide in the class of 2017. (It’s Graham’s bad luck that his players are peaking while he sits jobless. Maybe not so bad: ASU bought him out for $12.3 million.) ASU’s needs were more dire on defense. True freshman Merlin Robertson, a four-star outside linebacker who committed to ASU after Edwards and new linebackers coach Antonio Pierce (the ex-Giants Pro Bowler and Edwards’s former ESPN comrade) came aboard, was named national defensive player of the week after ASU’s second win. Pierce also helped ASU beat out USC for four-star corner Aashari Crosswell, whom Pierce coached in high school; earlier this month Edwards named Pierce his recruiting director.

And even though the coordinators departed, Edwards has done well rounding out his staff. He promoted receivers coach Rob Likens to offensive coordinator and he hired San Diego State’s defensive coordinator, Danny Gonzales, for the same role in Tempe. Gonzales runs a 3-3-5 scheme that Edwards likes, but mostly what Edwards likes is that Gonzales is a hard-ass who will attempt to toughen up a unit that allowed 32.8 points per game in 2017.

Sometimes administrators, writers, fans and all the rest can make college football too complicated. How much more is there to it than getting your guys?

By and large, Edwards was hired to outdo Graham, but in academics and character development, administrators want Edwards to build on the foundation Graham left behind. Not long ago ASU consistently ranked among the nation’s top party schools, and under coaches Dirk Koetter and Dennis Erickson, the Sun Devils could be undisciplined (or worse) on and off the field. The university has sought to banish those perceptions. ASU now touts its four consecutive years ranked as U.S. News and World Report’s Most Innovative School, and the 12 straight semesters student-athletes have had a cumulative GPA above 3.0.

Edwards is fixated on team harmony and says he can still see through a player’s eyes. “I was a bit of a rebel when I was young,” he says. “I would question authority; I was looking for knowledge.” His dad wanted him to go to Stanford; he went to Cal, then he quit the team. Twice. Still, those heady days on Sproul Plaza in Berkeley—where Herm, “an athlete with an Afro trying to figure out who I was,” would sit as students and professors extemporized on the issues of the day—prepared him for today’s cultural moment, when football itself, among countless other topics, divides the country.

“Oh, there’s a lot of correlation. It’s the same questions—how do we culturally understand each other? What makes us different? Well, besides our skin color and our nationality and maybe our religion, nothing,” he says. “We all want the same thing, we all want to have success in America.

“But that’s what I love about sports. You walk into a locker room and say, Oh, this dude’s got an accent. This guy’s got green hair. This guy’s got tattoos. But you go, Hey, it’s all good! They’re my teammates, man! And you’re gonna fight for ’em.”

Ten months into the job, Edwards seems to have won his players over. Tweeted sophomore cornerback Chase Lucas, in response to a video of Edwards after the Sun Devils’ second win: “I love my coach bruh. . . . I love my team.”

It is too soon to judge whether ASU’s Edwards experiment is working, and it will be too soon for a while: Edwards was hired to make Tempe a destination for top prospects, and not until the early signing period in December can we know if he has done so. What is apparent already, though, is that Edwards has people talking about the Sun Devils, and in a tone distinct from the one they used when he was hired. Those steps from derision to skepticism to curiosity are not easy ones to compel college football fans and analysts to take. Edwards entered the season with the goal of winning the Pac-12 South, and that goal seemed less lofty after ASU upset Michigan State on Sept. 8. The following week, though, a San Diego State team missing its starting quarterback rushed at will on the Sun Devils’ previously sturdy defense.

Still, after a late touchdown and an Aztecs fumble, Edwards’s team had a chance. With 14 seconds left, on a fourth-and-10 from midfield, Wilkins landed a miracle pass in the arms of receiver Frank Darby, who caught the ball inside the five-yard line and was summarily drilled up high by an Aztecs DB. The player was ejected, upon replay review, for targeting. But the review also found, dubiously, that the ball touched the ground after the hit. ASU would therefore take its last shot at the end zone from the 35 rather than the four-yard line and lose the game. The fans who were still awake—the game ended after 2 a.m. on the East Coast—awaited an epic postgame session with the media after the disputed ending. But none was coming. “We thought he caught it. When they reviewed it, all bets are off. Obviously, they said he didn’t catch it, so there you go.” The onetime maestro of the postgame presser sounded like nothing more or less than a regular college football coach.