With an Offense Learning to Fly, BYU Is One of 2018's Biggest Surprises

Welcome to the Film Room. This is a weekly analysis of one big play, series, scheme or idea from the weekend’s slew of college games and deciphering what it means going forward.

Tanner Mangum had to learn how to multi-task better. All quarterbacks multi-task to some degrees: relaying the play call from the sideline, reading a defensive formation and then dancing around pass rushers before getting the ball out—but Mangum has never had so much to do before a snap. His checklist in BYU’s new offense, which former LSU O-line coach Jeff Grimes brought to Provo when he was hired to replace Ty Detmer this offseason, includes shifting and motioning as many as five players on any given play. Often, that presnap activity ends with one of the staple plays of the Cougars’ offense: the fly sweep, more commonly referred to as a jet sweep (while offensive terminology differs from program to program, BYU uses “fly” and “jet” interchangeably).

Let’s take one play from the Cougars’ 24–21 upset win over Wisconsin in Week 3 as an example.

Here’s all the movement that happens before the snap:

1. Tackle Brady Christensen (No. 67), lined up at tight end, lumbers from the right side of the offensive line to the left.

2. Tight end Moroni Laulu-Pututau (No. 17), lined up at tackle, moves from the left side of the line to the right.

3. Tight end Dallin Holker (No. 32), lined up in the H-back spot just behind the line, follows Laulu-Pututau to the right side.

4. With a flick of his foot, Mangum sends slot man Aleva Hifo (No. 15) in motion. Hifo races behind Mangum under center, then doubles back the way he came as the ball is snapped to either take a handoff or feign like he is.

There are other plays in which a slot receiver moves to tailback, a wide receiver moves to the slot and three tight ends break the huddle lined up bunched together out wide, only to shift to their more typical in-line position. It’s a lot to take in.

“Fly sweeps, jet sweeps, shifts and motions, that’s us,” Mangum says. “Having to remember all the shifts and motions and formations and remembering I have to read the defense ... well, when we were first installing it, I’d be so busy thinking about [the shifts and motions] that I lost track of what the defense was doing and what my read was.”

All is well now. Mangum has become a multi-tasking wizard, and Grimes’s new sweep-heavy, motion-filled offense has helped BYU surge to a 3–1 start and a No. 20 ranking in the AP poll ahead of a trip to No. 11 Washington. The Cougars’ offense has been far from prolific, averaging just 320 yards a game so far, but it has been effective, producing crunch-time scores on the road against Arizona and the Badgers, and it has hogged the ball to keep BYU’s strong defense rested.

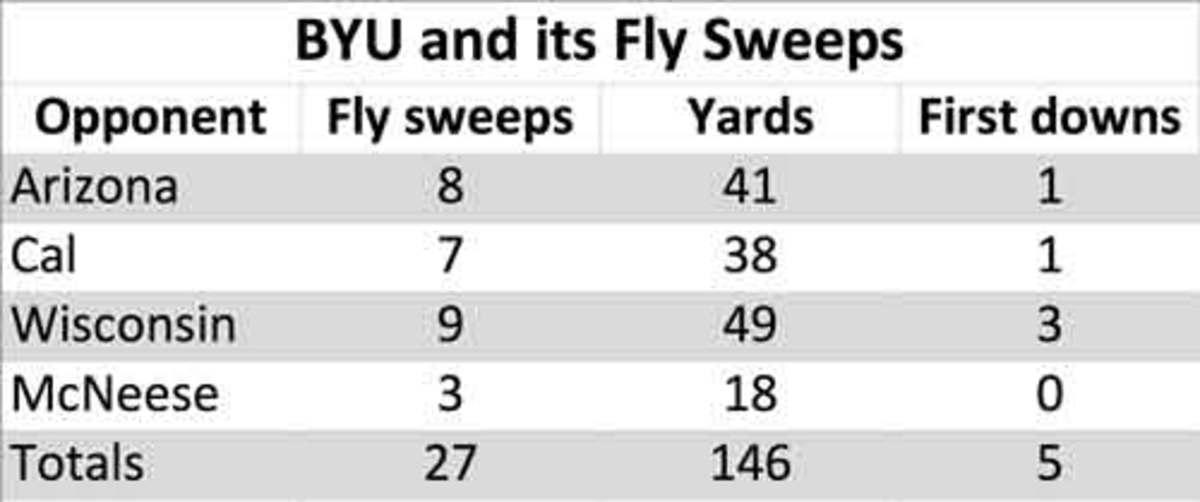

Grimes is succeeding with a unique brand of football, a misdirection scheme that incorporates fly sweeps like the one atop this story. BYU has run 27 sweeps in its first four games that have gained 127 yards, a 5.4-yard average. The concept worked to perfection against Wisconsin, gaining 49 yards on nine sweeps and picking up three first downs. “It’s been great for us, being able to use different players in that [sweep motion] and spread the ball out more,” says third-year BYU head coach Kalani Sitake. “I’m a defensive guy. That’s my background. It’s a difficult scheme. As an offense, it keeps guys guessing.”

In the simplest form, the fly is based around stretching the field horizontally. A player sprints laterally behind the line of scrimmage before the snap, usually passing just behind the quarterback under center or just in front of him in the shotgun. The motion man is a threat as a runner or a receiver. In a way, it is an inverted triple option, and like the traditional triple option, it is a pain for defenses to defend. Maryland interim coach Matt Canada made headlines both positive and negative when he brought it to LSU last season, averaging well over six yards a sweep in SEC play to shake up a conference that crows about its downhill running style and its athletic defenses built to stop the run. (Canada and head coach Ed Orgeron butted heads over the system’s complexity, among other things, which led to Canada’s departure for College Park.)

Sitake gave Grimes his first coordinator job over the offseason, looking to install the same scheme that LSU blistered his defense with in a 27–0 Tigers win last year in New Orleans. Grimes says only a portion of his offense is derived from what Canada runs, but the schemes’ common feature is their most obvious one: About three-fourths of BYU’s offensive plays involve at least one player shifting before the snap. In all, the Cougars have shifted or gone into motion before the snap more than 220 times in four games. “I’ve seen how it can keep defenses off-balance,” Mangum says. “It’s been fun.”

“The willingness to say, ‘We’re going to line up in any given formation and we might shift to it from any given formation on any given down and distance,’ is something I got from Matt,” Grimes says. “I saw the value in it last year.”

The presnap sweep motion is essential to the scheme. Grimes learned it during the first big break in his coaching career as an assistant for Dirk Koetter at Boise State in 2000. Koetter’s offensive coordinator Dan Hawkins had brought the fly system to Boise from Willamette College, then an NAIA program in Oregon. The roots of the fly sweep are in the desert valley of California, where a high school coach named Gene Beck is believed to have created the system. (The full timeline of the scheme’s dissemination can be found at the bottom of this story.) Koetter’s success at Boise State resulted in him landing the head job at Arizona State in 2001.

“When Dirk left for Arizona State, he asked me for two favors,” Hawkins said in an interview last year. “One of them was, ‘Don’t give away anything on the fly.’”

BYU has used at least eight different players on sweeps, none more than junior receiver Aleva Hifo (12 carries for 67 yards). The biggest gains on the play (14, 13 and 12 yards) came against Wisconsin; BYU opened the game with sweeps on six of its first 11 plays, scoring a touchdown on its second drive to set the tone for a stunner. Sitake already had gained enough confidence in Grimes’s scheme by the season-opener that he went for it twice on fourth down in a 28–23 victory at Arizona. He’s just hoping his offensive coordinator doesn’t leave anytime soon.

“He’ll be a head coach someday,” Sitake says of Grimes. “He doesn’t care about stats other than winning. He doesn’t need to pad his stats. He just wants to do whatever’s best to win the game, and that’s a true O-lineman: get no credit, do your job and be happy with the result.”

Sitake even let Grimes run a trick play against Wisconsin. “Bucky” was designed just for the Badgers and named after their mascot. The play went for a 31-yard touchdown. Mangum threw a lateral pass to Hifo that was designed to look like a quick screen, and with the defense drawn up, Hifo turned and threw downfield to the wide open Laulu-Pututau. Aaron Roderick, BYU’s pass game coordinator and quarterbacks coach, was behind the concept, which he had seen Boise State run in the past. “We looked at a video of Boise running that play. It fit for me. We decided it on Monday and practiced it every day,” Grimes says. “Timed out perfect and it worked out just like we saw Boise do it.”

The Cougars executed the play on a second-and-four in the second quarter. “It was awesome,” Sitake recalls. “Before we even ran the first-down play, [Grimes] said, ‘The next call is going to be Bucky.’ I was like, ‘Wow. O.K.’”

Sure, Grimes misses spending time in the offensive line meeting room, but his transition to coordinator went smoother than most because of the situation he inherited—that is to say, one where there was nowhere to go but up. The Cougars finished 124th in the FBS in scoring offense last year, scoring more than 20 points in just four of their 13 games. They are already one away from matching that total in 2018, with Washington’s stout defense looming as the season’s toughest test.

“They had not been very good,” Grimes says. “That’s usually a good thing as a coach. You have the opportunity to have an immediate captive audience. Their being willing to do whatever we say gives them a chance for success.”

That includes shifts and motion before the snap and those sweeps. Mangum is a pro in the system now, a 25-year-old sixth-year player who can juggle moving parts before a play gets off the ground with the best of them. Reading defenses, relaying play calls, completing passes in a collapsing pocket and triggering one of the oddest things you’ll see in football: a 300-plus-pound tackle trotting behind his quarterback before the snap. “Oh yeah,” Mangum says, “that was new for us.”

Tracing the history of the Fly Offense

Gene Beck: Many believe he was the first to use the offensive system back in the 1950s, and the invention won him so many games at Delano High School in California that the school has a bust of him in its library. To this day the offense is used widely by high schools near Delano in the Central Valley (inland California from Los Angeles to San Jose). Many in the area’s large immigrant community refer to the offense as La Mosca, or “The Fly” in Spanish.

Phil Maas: Maas, another high school coach in the Central Valley, used Beck’s scheme to win three league titles before he brought it to his next stop, a high school in Monterey, Calif. For the last 37 years, Maas has coached at College of Siskiyous, a community college just south of the Oregon state line.

Dan Hawkins: After learning the system on Maas’s staff at Siskiyous in the late 1980s, Hawkins led Willamette College to the NAIA championship game, which propelled him to the offensive coordinator job at Boise State, where he exposed the fly to major college football. Hawkins, after head coaching stops at Boise State and Colorado, is now the coach at UC Davis, where his RBs coach is Mark Speckman.

Mark Speckman: Maas calls Speckman the “modern father” of the fly, a man who, after picking up the offense while on staff with Maas in Monterey, used high school clinics to spread the system far and wide. Speckman was on Hawkins’s staff at Willamette College before taking over the program and winning 82 games in 14 seasons, breaking program rushing records in the process.

Dirk Koetter: With Hawkins running his fly-centric offense, Koetter and the Broncos rolled to back-to-back 10-win seasons in 1999 and 2000, jump-starting a dynasty of efficient offenses at Boise State. The Broncos’ success got Koetter the job at Arizona State, and he brought a young offensive line coach named Jeff Grimes to Tempe with him.

Matt Canada: Canada learned the offense directly from Speckman, a man coaches consider one of the most overshadowed offensive innovators of his generation. Canada adopted the offense and has “taken it to another level,” Speckman says, while at jobs at Pitt, LSU and now Maryland. He worked with Grimes last year in Baton Rouge.

Jeff Grimes: Grimes, in his first year as an offensive coordinator at BYU, is using a similar system to what Koetter used with success at Boise State nearly two decades ago and what Canada refined at LSU in 2017.