Assigning Blame and Credit for Penn State's Fateful Fourth-Down Failure

Welcome to the Film Room. This is a weekly analysis of one big play, series, scheme or idea from the weekend’s slew of college games and deciphering what it means going forward.

Four days later, the fallout from Penn State’s failed fourth-down conversion attempt still lingers. Ohio State stuffed Miles Sanders’s fourth-and-five run to preserve a 27–26 victory that should impact college football’s postseason more than the average September top-10 clash. Questions linger. Why did the Nittany Lions choose that play? Why didn’t it work? Who deserves credit and blame for the biggest play of the season’s first month?

These questions do have answers, some of them complicated. Based off conversations with a handful of experts, we try to unpack those answers in four sections below, explaining 1) how the presnap shifting eventually resulted in confusion on the Penn State offensive line; 2) why the option Penn State chose broke down; 3) what could have happened had quarterback Trace McSorley pulled the ball out of Sanders’s midsection and 4) whether James Franklin and offensive coordinator Ricky Rahne’s play-calling tendencies helped or hurt the Nittany Lions’ chances.

Before the Snap

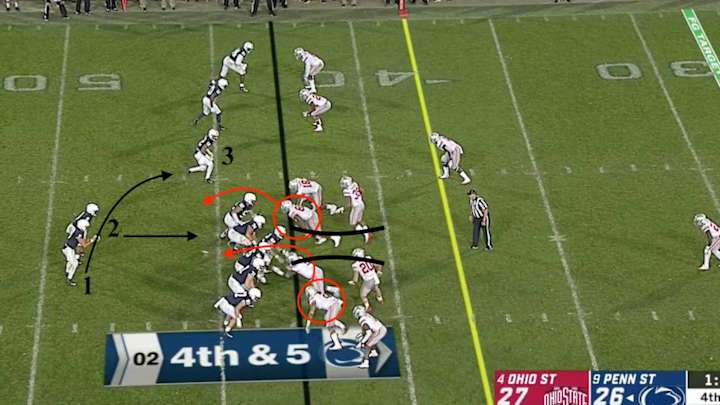

A chess match unfolds before the snap. Ohio State coach Urban Meyer called timeout after seeing Penn State’s formation, and the Buckeyes came back out with a fourth down lineman in their defensive front. As a reaction to the change, Franklin took a timeout, and Penn State returned to the field aligned in the pistol, with Sanders behind McSorley. Then, just before the snap, they shifted back into their original formation, with Sanders aligned next to McSorley in the shotgun.

The final shift takes place a half-second before the snap: Sanders moves from McSorley’s right to his left, a potential shift to attain a numbers advantage since the Buckeyes had stacked the right side of the formation. But Ohio State answers with its own shift, spreading out its linebackers to follow Sanders as the ball is snapped in a move that results in confusion on the Penn State offensive line. That’s why the most important factor in this play’s failure is not the call, says former Auburn offensive lineman and SEC Network analyst Cole Cubelic: “It is 100% execution.”

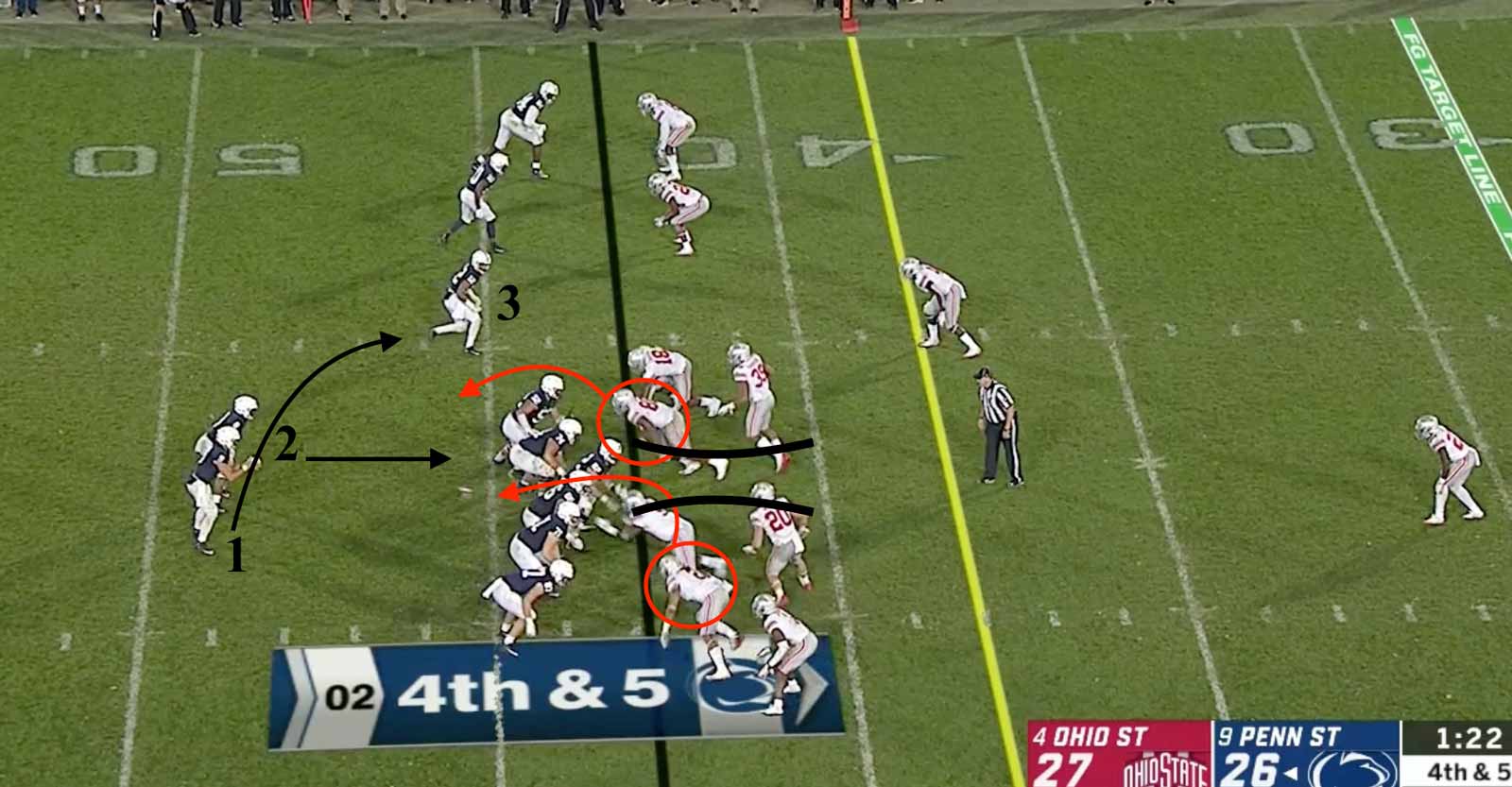

At the snap

This is a zone-read with a bubble screen as a decoy third option. To many defensive coordinators, this play works like an inverted triple option that could result in a McSorley keeper, a Sanders dive or a bubble screen to slot receiver Mac Hippenhammer. The Nittany Lions like the way Ohio State’s front is positioned in the above photo. It gives them what McSorley called a “crease” up the middle, indicated by the black alley bars. The problem: Sanders can’t reach the alley because of a twist executed by Ohio State end Chase Young, and McSorley cannot keep the ball to the outside because of the presence of Ohio State tackle Dre’Mont Jones (both are circled in red in the above screenshot). Left tackle Ryan Bates misses Jones, and right tackle Will Fries and right guard Connor McGovern do not pick up the twist by Young.

After the snap

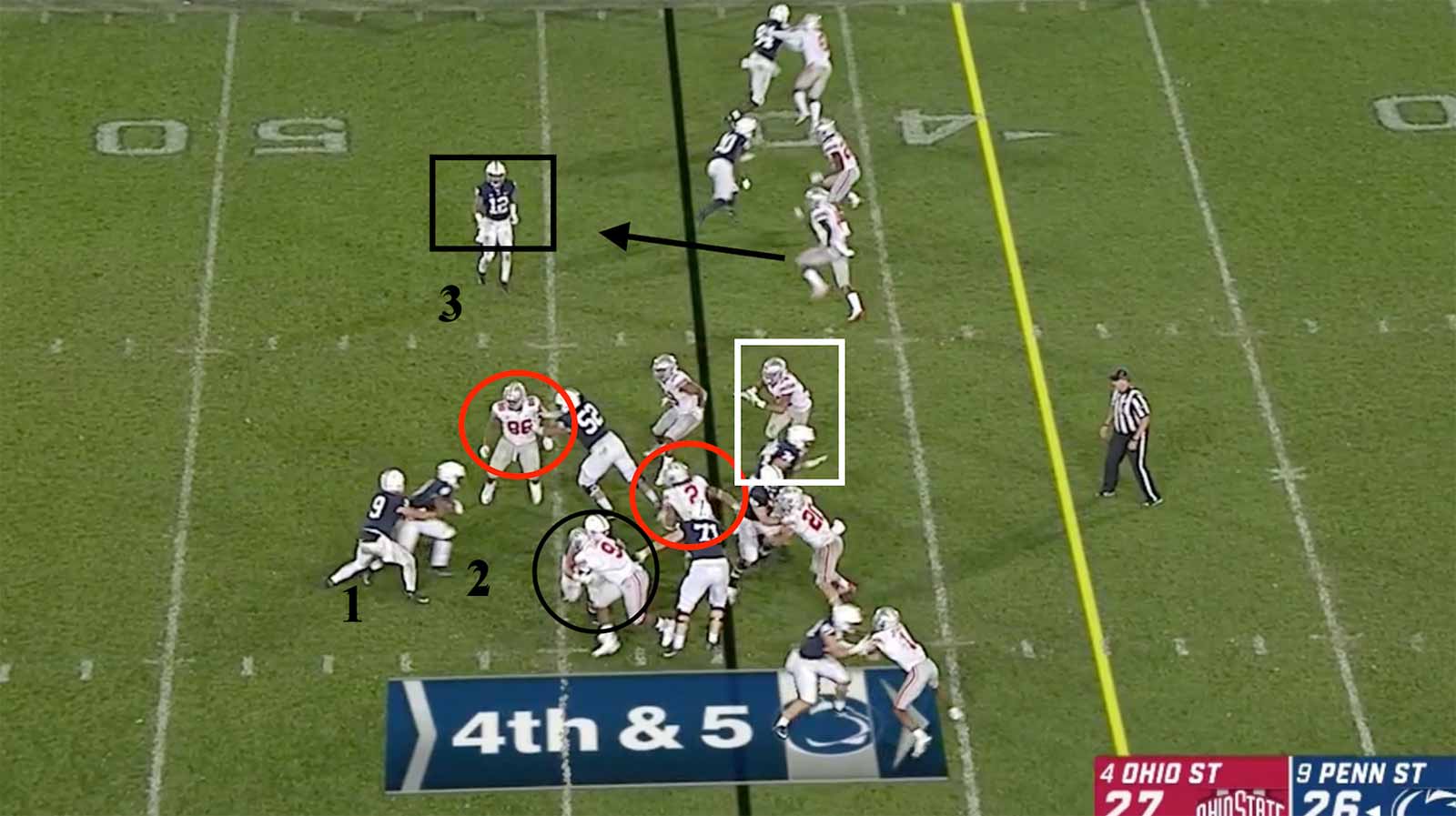

You can see how much penetration that Jones and Young get even before McSorley has handed the ball to Sanders, winning on the outside and the inside to completely blow up the play. The bubble screen is taken away, too, as OSU strong safety Jordan Fuller (black arrow) races to meet Hippenhammer, squared in black. But what if McSorley had immediately thrown to Hippenhammer at the snap? Big Ten Network analyst Gerry DiNardo believes the Nittany Lions would have gained the first down because of the “cushion” Fuller gave the receiver at the snap. “If Trace McSorley throws it to No. 12, he’s going to gain five yards,” DiNardo says. Meyer said after the game that Ohio State anticipated a zone-read, but from the looks of Ohio State’s defensive formation, the Buckeyes were expecting a pass, DiNardo says, and that very well could have scrambled blocking assignments on the offensive line. (After all, DiNardo adds, how often do teams practice run plays against pass looks?)

A presumed third missed assignment is highlighted in the white square, which incorporates left guard Steven Gonzalez and OSU linebacker Malik Harrison. If Young doesn’t make the tackle on Sanders, the unblocked Harrison has a shot, as does linebacker Peter Werner, who a half-second later sheds his block from PSU center Michal Menet (just under the white box). DiNardo notes that the real key to the play is Ohio State DT Jashon Cornell, circled in black, who grabs McGovern, the right guard, opening a hole for the twist from Young. “He’s tackling the guard so the guard can’t block [Young],” DiNardo says. That leaves right tackle Fries (No. 71) responsible, and he’s unable to physically make the play.

This play was doomed every which way, but especially up the middle, where PSU was outnumbered 6–7 in blockers to defenders. That’s probably why Franklin admitted that it was a poor play call afterward.

Revisiting the play call

So how likely is it that Ohio State saw this play coming? On 15 third downs of four to six yards this season, Penn State has put the ball in McSorley’s hands, to run or pass, 11 times. Only three of those 11 opportunities were converted into a first down. Three of the four non-McSorley attempts were picked up on the ground by a running back, including a Sanders 12-yard rush against Appalachian State.

What about on fourth downs, you might ask? In the last two and a half years, Penn State has attempted 40 fourth downs, converting 22 of them. Excluding Saturday’s fourth-quarter play, four of those 40 fourth downs were of four to six yards, and Franklin passed the ball on three of those. McSorley completed all three of those passes, but two came up short of the first-down sticks. (Saquon Barkley ran fo a first down on the fourth attempt.)

So, Penn State’s history under Franklin says they would have passed there. They did the opposite, and it stunned everyone, including ESPN analyst Kirk Herbstreit, who told a national audience seconds after the game, “I am shocked by the play call.”