How Laviska Shenault Jr.'s Life of Competition and Perseverance Have Led Him to the Spotlight

DALLAS — The socks were filled with whatever: a plastic stick of deodorant, the remote control to the television, loose change or car keys. These were playful weapons of battle in the Shenault household—an athletic and able-bodied family with a father who cut loose with his children as if he were their age. Laviska Jr. and his brother La’Vontae launched the fistfuls of bulging socks across the family’s living room, targeting their father in a silly game that sometimes left holes in the wall.

Sock bombs paled in comparison to their indoor BB gun battles. This family of eight was fueled by competition, led by a mother who played college basketball and a 6’ 2”, 230-pound father. Split on gender lines, the family played four-on-four basketball games, and there were football matches, too, where mom Annie served as the all-time quarterback. There were bike races through the Glenn Heights neighborhood of suburban Dallas and go-cart races at the local adventure parks. Inside the home, the most intense competitions raged in front of the television, something known in this family only as “The Game.” Laviska Sr. often challenged his children in The Game—Madden NFL, NBA Live, NCAA football and whatever other sports-related Playstation disc someone slid into the console. The penalty for losing in The Game was standard and not debatable. “Pushups,” smiles La’Vontae.

A decade later, Laviska and La’Vontae are still engrossed in competition. Laviska is one of college football’s emerging stars at Colorado, a do-it-all receiver who’s helped the 19th-ranked and 5–0 Buffaloes to their best start in 20 years. La’Vontae is a senior wideout for DeSoto High who’s committed to Texas Tech. They both play for the man who introduced them to sports.

On July 17, 2009, Laviska Sr. was killed in a pedestrian incident along Highway 12 in southeast Irving when two vehicles, an F-150 pickup and a 2003 Acura, struck him. A report in The Star-Telegram at the time says it was unclear why he was on foot near the bustling highway that wraps around Dallas. Annie Shenault believes her husband slipped as he was switching to the passenger seat to let her drive, their vehicle pulled to the side of the road and their children inside the car. “It all happened so quickly,” Annie says. “It was one of those things you can’t explain.” Three years later, almost to the day of her husband’s death, Annie contracted West Nile Virus from a mosquito bite, a disease that put her in the hospital for weeks and incapacitated her for months. It took a year for her to walk upright again.

The Big Ten's Path to Sending Two Teams to the Playoff Is Very Specific but Very Real

This is a story of perseverance, how two young boys, a strong mother and tight-knit family endured the worst of obstacles and now—because of competition—find themselves in a bright spotlight, their second-youngest member stepping onto the national stage this weekend in Los Angeles. Laviska leads Colorado into a game with powerhouse Pac-12 rival USC (3–2) on Saturday night in The Coliseum. A down year for the Trojans presents an opportunity: The Buffaloes have never beaten them in 12 tries. And they’ve got one of football’s sharpest weapons this year, a guy called Viska.

Laviska Shenault leads the nation in receiving yards a game (141.6), has scored more touchdowns (10) than anyone playing in five or fewer games and is a few days removed from the most scintillating showing of his career. In a 28–21 win over Arizona State last Saturday, Viska, just a sophomore, was responsible for all four touchdowns, displaying the versatility and varying skills that now have him, at least in one poll of voters, a Heisman Trophy contender. “What he’s doing now is unbelievable,” says Brandon Harrison, Viska’s former position coach at DeSoto High in the southern outskirts of Dallas.

Viska’s life is changing by the week, each performance pushing his stardom to another limit, thrusting a quiet, shy kid into the public eye. He can no longer walk across the Colorado campus without students pointing and whispering. “That’s Honcho,” they’ll say, another nickname for this 6’ 1”, 220-pound chiseled freak. “It’s starting to get crazy,” says the kid who models his game after Falcons receiver Julio Jones.

Viska admits that he’s even surprised himself with a sophomore spurt that rivals the one Arizona quarterback Khalil Tate had last October. He’s a late bloomer, a three-star rated prospect in the 2017 signing class who spent his middle school and high school freshman days on DeSoto’s ‘B’ team. “He wasn’t a guy that as a sophomore you knew was going to be great,” says Todd Peterman, Viska’s head coach. He played junior varsity as a sophomore, caught only 27 passes as a junior and finally bust out with nine touchdowns as a senior, regularly clocking 22 miles an hour in games and leading the Eagles to a 16–0 record and their first state championship.

Colorado finished 5–7 last season, Viska had only seven catches and co-offensive coordinator Darrin Chiaverini knew he needed to do something. In the spring, he scribbled on a whiteboard ways he could use an athlete who is thick enough to block, fast enough to play receiver and strong enough to run the football. “I came up with, ‘Let’s just play him everywhere,’” Chiaverini says. Viska has been deployed as a tight end, a wide receiver, a slot receiver, a tailback, a wing-back, an H-back and the quarterback in the Wildcat. He feels like he’s back in high school, where Peterman constructed an offensive package for him called “Hawk,” says Harrison.

He was in full flight against ASU. He scored a touchdown on a direct snap by powering in between the tackles, caught two long scoring passes while out-running his competition, snatched a jump ball off a flea-flicker reverse pass and turned a short slant pass into a score. He’s tough to double team, ASU coach Herm Edwards said after the game, and UCLA coach Chip Kelly two weeks ago called Viska the best receiver in a Pac-12 loaded with explosive players. “I move him around so much, they don’t know how to double team him,” Chiaverini says. “Opposing coaches have told me that they don’t know where he’s going to be so they can’t devise a plan for him.”

Chiaverini and Viska have a special bond. He gets Viska to open up more than others, Peterman says. Viska is such a shy kid that recruiters cycling through DeSoto had no idea what the prospect thought of them or their school. “He had three answers for them: yes, no and maybe,” Peterman says. “It was like pulling teeth, but not for Coach Cheeve.” From his days on the staff at Texas Tech, Chiaverini knew about Viska at a young age and was one of the first to offer him a scholarship, followed by the likes of the Alabamas and LSUs. He turned down Nick Saban and Les Miles, both whom visited his high school, picking little Colorado. “I wanted to go somewhere not on the map already,” he says.

He likes the mountains, the thin air and cool temperatures, too. He misses just two things about home: his family and his favorite eatery. “I wish they had Whataburger up here,” he laughs. College has changed Viska. He’s breaking free of that bashful demeanor that’s lingered for years. He’s even started dancing, something those back in Dallas never thought possible until they saw proof on Instagram and Snapchat videos. “To see that,” says a smiling Harrison, “it’s, uh, different.”

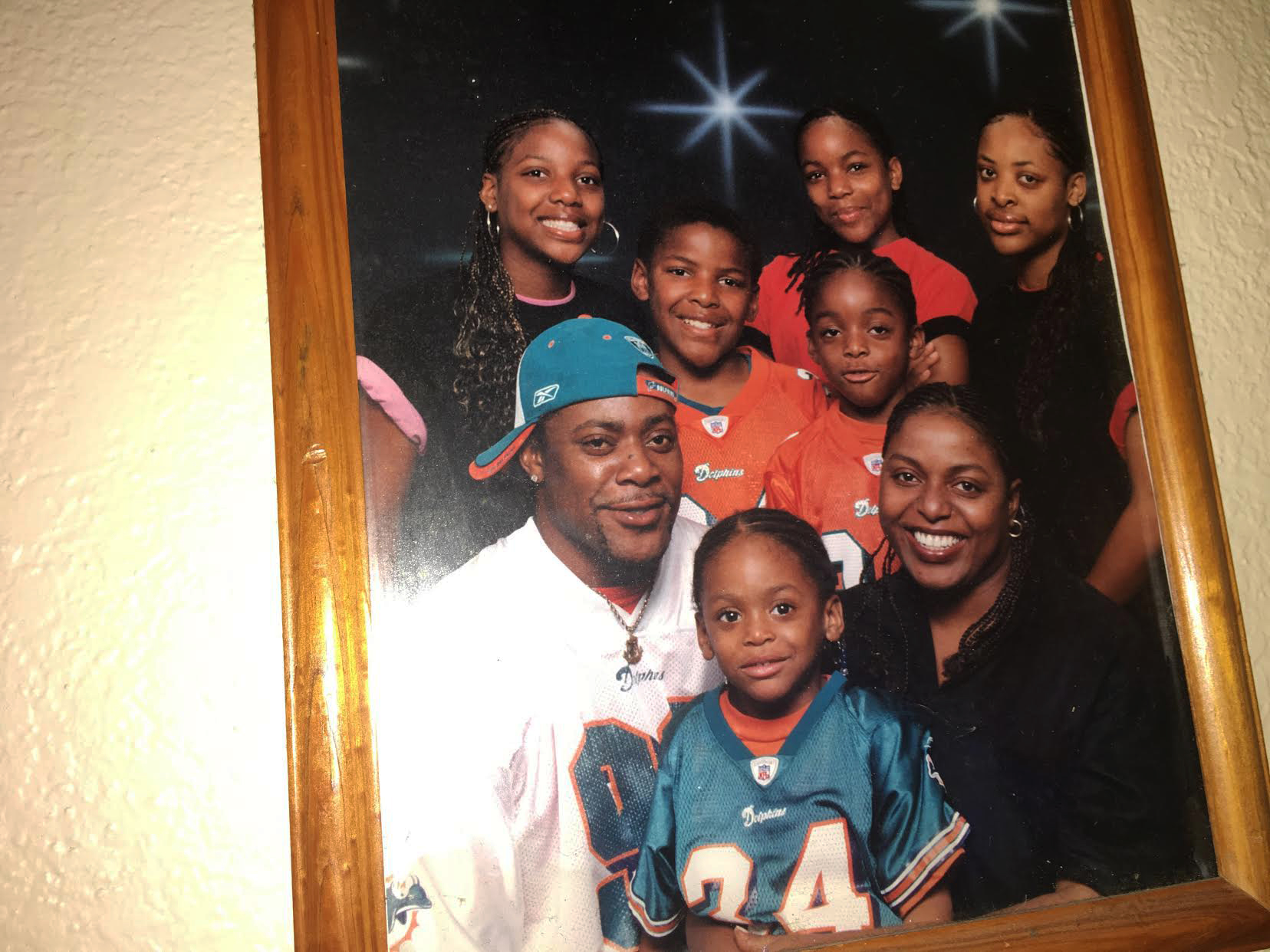

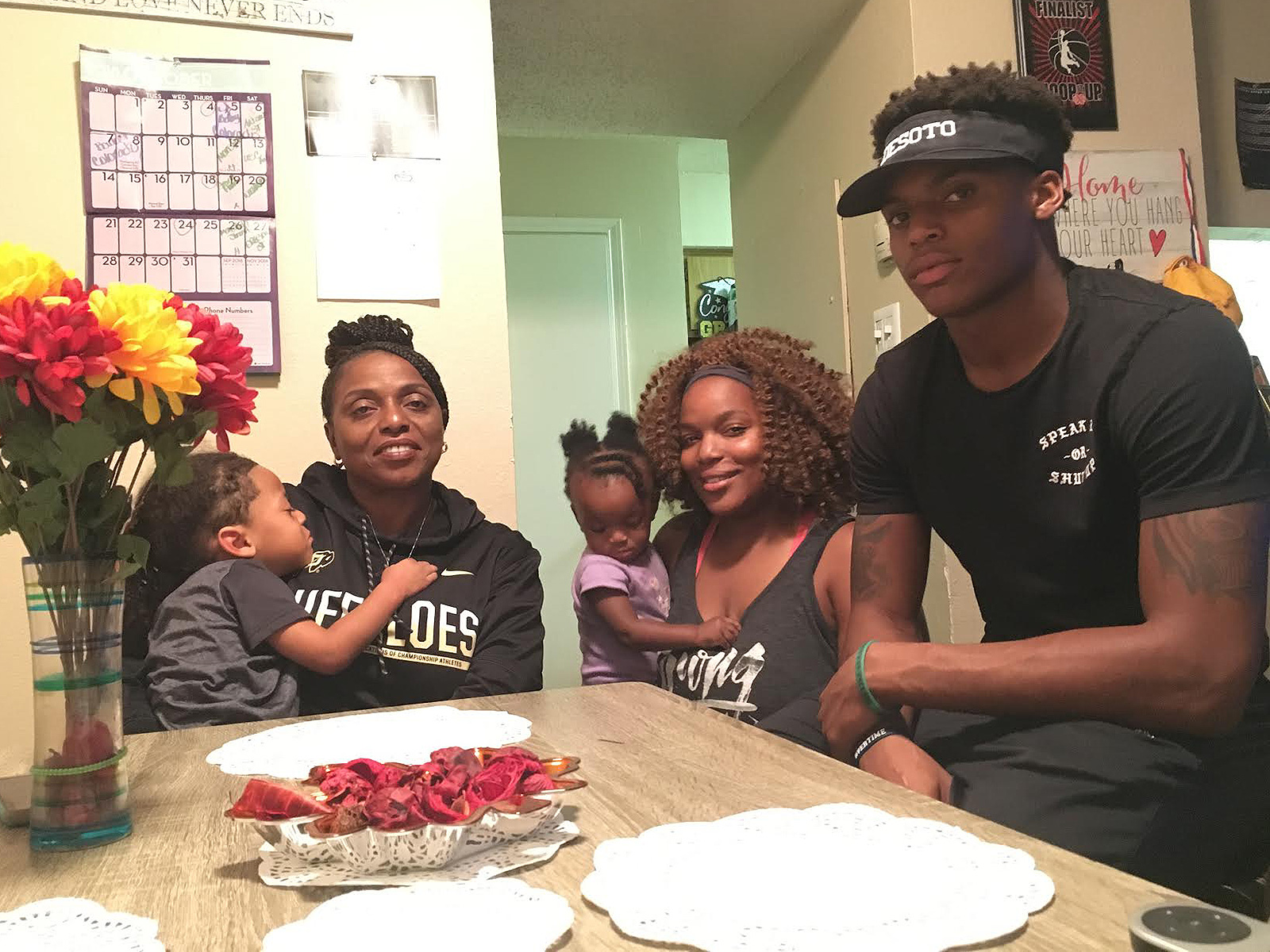

Back in DeSoto, part of Viska’s family—he’s known here as “Junior”—has gathered inside Annie’s small apartment, around a dining room table no bigger than a tiny work desk, attached to a living room crammed with memorabilia from her two sons’ athletic careers and her husband’s life. A family portrait hangs on one wall, taken a few months before Laviska Sr.’s death. Dad is decked in Miami Dolphins gear—a jersey and backwards hat—to match the outfits worn by his three boys: Viska (now 20 years old), La’Vontae (18) and Calvin (24), the latter a son from a previous relationship. His three daughters are on the back row: Dominique (30) and Terri (28), Viska’s half-sisters, and Tyanna (24).

Viska handled his father’s death internally, he admits. “I was the different one out of the whole family,” he says in an interview this week. “I wasn’t the one always in my feelings.” The family was somewhat separated after the incident. Dominique was already living away from home, Terri started college a month later and Calvin moved to Atlanta to live with his mother. The financial toll was high. Annie had to move into a part-time role at Home Depot so she could care for her children, and Laviska Sr.’s income as a welder stopped. The family lost its home. Tyanna, at the time the oldest child in the house at 15, saw her academics slip before she snapped out of the funk. “I thought of my younger brothers,” Tyanna says. “They were seeing their sister… I look at it like, ‘They’re going to look up to me.’”

For the boys, their birthdays are the hardest and most emotional. “You just try to pick them up,” says Harrison, who now coaches La’Vontae at DeSoto High. Annie visited Colorado to celebrate Viska’s 20th birthday last week and watch from the stands as her kid had the game of his career.

Annie still holds records for points (25.6) and rebounds (15.5) per game at the University of Dubuque, a Division III school in Iowa. She’s a confident woman, quiet at first during a meeting with a reporter before opening up. She picks with her children about her glory days of dominating the post. Those four-on-four family basketball games were won “by the girls,” she says confidently, before La’Vontae gives an eye roll. In her hometown of Drew, Miss., Annie is still known as “Mageec,” a play off of Magic. She idolized Magic Johnson. Her rallying cry to this day dates back to those high school days. Her sons know it well.

Who better than me? No-bod-eeee.

I’m something like unique.

That’s why they call me Mag-eec.

Viska began playing basketball before football. His father watched a year of his son shoot hoops for the DeSoto Bulls. His death arrived well before Viska learned to dunk. As a tribute to his father, Viska’s hair hasn’t been cut since his death. His dreadlocks are a staple, falling well below his shoulders. His hair prevented him from playing high school basketball because of a code enforced by the DeSoto High boys’ coach. “I didn’t have a hair policy,” Peterman says.

There are other tributes to Laviska Sr. around the Shenault home. A Miami Dolphins afghan, for instance, is draped over the living room couch. Laviska loved Dan Marino. “I’m still a Dolphins fan,” Annie says. La’Vontae was 8 at the time of his father’s death. He only began to play sports afterward, and now he sits in a similar position to his brother two years ago: DeSoto High’s receiving leader but a somewhat underrated prospect in a talent-laden state. La’Vontae is smaller than Viska. While his brother worked in the weight room during the offseason, La’Vontae, with closely cropped hair, was on the court, a reason for their different physiques. Viska’s strength is something of a legend at DeSoto—and Colorado. He recently set the CU record for squating at 500 pounds, more than twice his body weight. “He’s special,” says Chiaverini.

In more ways than one. In the aftermath of his father’s passing, his mother spent nearly a year fighting West Nile Virus. One morning, Annie turned to lift herself out of bed and fell to the floor, too weak to stand. She was one of more than the 1,000 people in a Dallas-area West Nile outbreak in 2012 that killed 36 people. Tyanna returned home from college to help care for her brothers, and Annie’s mother visited, too. “I asked her one time, ‘Why me, mom?’” Annie says. “She said, ‘Why not you? What makes you any different than anyone else?’”

“We were always taught to be tough,” La’Vontae says. “Pick up and go on and push through. We’re going to make it through.” La’Vontae has set goals for his senior season: 1,300 yards (he’s got 400), 20 touchdowns (he’s got four) and a state title (the Eagles are 4–1 so far). But he and his brother have set the bar much higher. Asked about his brother’s next act, La’Vontae quickly fires a “win the Heisman Trophy” response. Beyond that, there are dreams of playing in the NFL, where the financial reward could make the hurdles worth the leaps. A group of people crippled by so much is on the way up.

“We’re doing this to help them, our family,” La’Vaontae says. “My mom and sisters. I do it for my family. He does it for the family.” Listening to her youngest, Annie wipes tears from her eyes. “We’re in position to change all of this,” he continues. “Why not us? Why can’t we change all of this?”