Travis Etienne Is a One-Man Show Trapped in a World of Running Back Committees

JENNINGS, La. – They all came to see Travis Etienne. Coaches from Arkansas, Alabama, LSU, Texas A&M and others gathered around the practice field at a small south Louisiana high school to see a running back who had only recently appeared on the radar screen of the college football recruiting world. Some coaches wielded small handheld video recorders. Others used their iPhones. All of them were hell-bent on producing evidence of this alleged speedster. A few minutes into practice, not only had Etienne not recorded a single carry, he hadn’t taken a snap.

“I refused to run him,” recalls James Estes, Etienne’s offensive coordinator at Jennings High. Two days earlier, Etienne strained his thigh during a track meet in one of the worst-timed injuries imaginable—in the middle of spring practice of his junior year. College coaches were here to see him run. Etienne wanted to run. Everybody was waiting for him to run. “You’re gimpy,” Estes told Etienne. “You don’t need to run.” What Etienne did next speaks to his competitiveness as much as his playfulness. He sneaked into the huddle with the scout team offense, replaced its tailback and proceeded to destroy his high school’s starting defense. “He had nine carries. He scored nine touchdowns,” Estes remembers. “He decimated the defense to a point where the defensive coordinator shut down practice.”

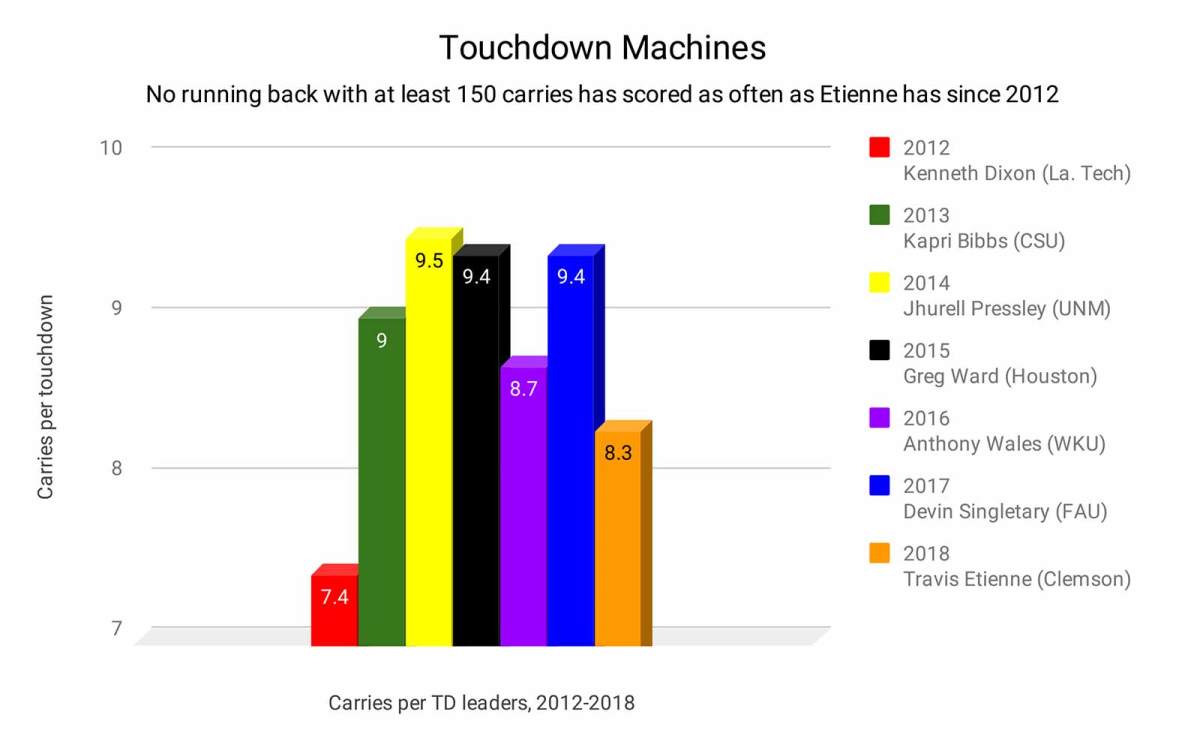

By now, you know how this story ends: College coaches got their video that day, and Etienne evolved quickly into an elite recruit, signed with Clemson and tore through the ACC as a sophomore this season, helping lead the Tigers back to the College Football Playoff. He was named ACC Player of the Year, landed on a bevy of All-America teams and set a school record for rushing touchdowns (21). He’s an elusive, explosive and physical back who will likely enter 2019 as one of the favorites for the top prize in college football, and he’s accomplishing all of these feats on a very limited number of touches. Coaches are still protecting Etienne, like Estes did that day in 2016, only for different reasons and in different ways. He is averaging just 12.6 carries a game, has only twice this year eclipsed the 20-carry mark and has gotten the call for less than 40% of Clemson’s overall rushing attempts. In short, he’s doing more with less—He’s averaging a touchdown every 8.3 carries, the highest frequency for a starting tailback in six years.

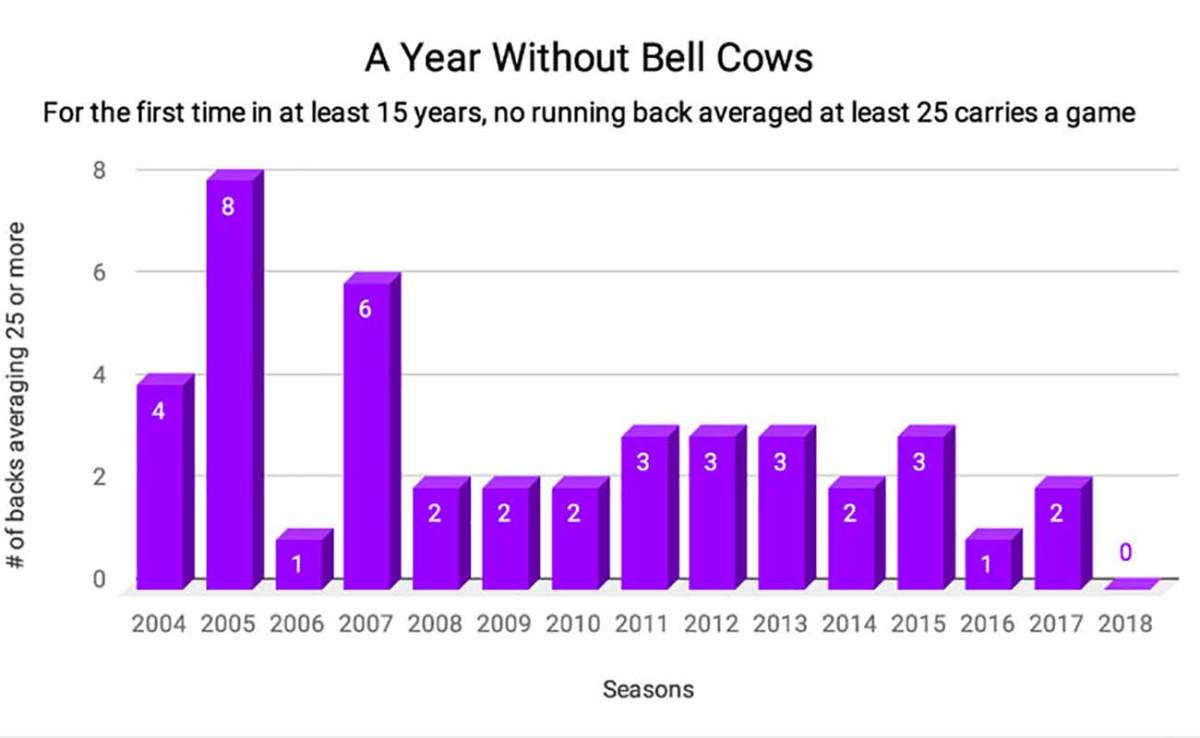

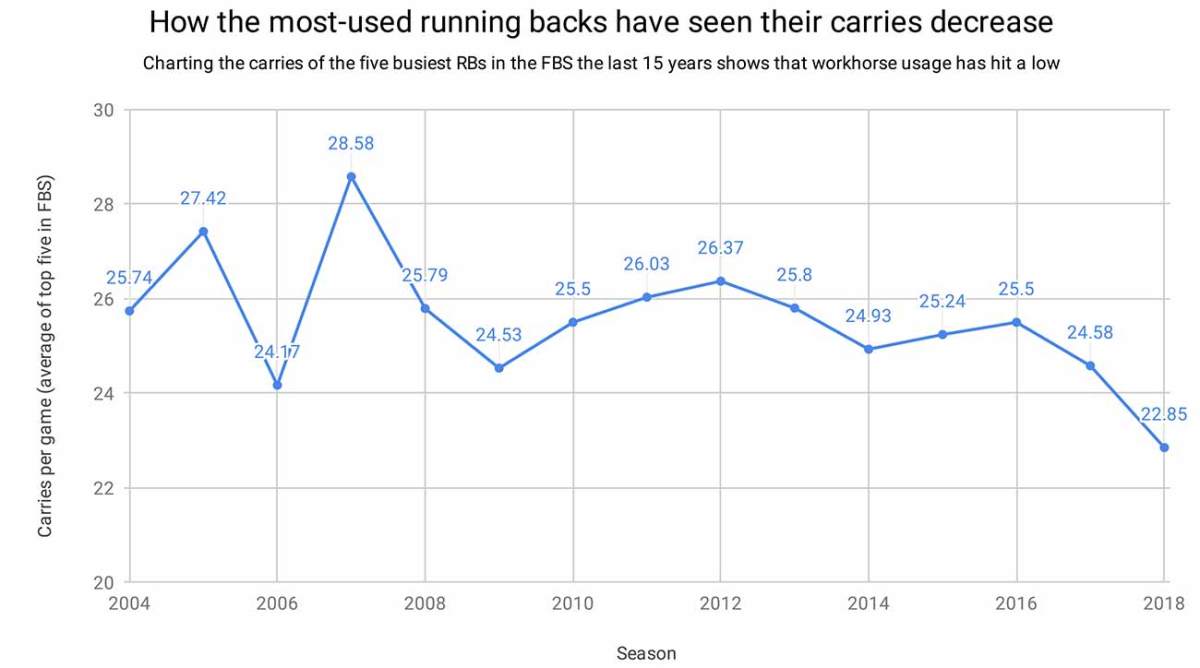

Etienne is the headliner of a movement in college football away from the bell cow back. The nation’s top rushers are seeing their carries decrease. For the first time in at least 15 years, no running back is averaging 25 carries or more a game. This season, the top five rushers by attempts are averaging 22.85 carries per game, the lowest mark since at least 2004. For a second consecutive year, none of the four playoff participants bring a rusher with 200 or more attempts this season into the semifinals. The first three playoff fields included seven such players. Of course, there are other factors this year beyond spreading the burden. Notre Dame’s No. 1 back Dexter Williams (142 attempts) was suspended for the first four games of the season, and Oklahoma lost leading rusher Rodney Anderson to a season-ending knee injury in Week 2. But Alabama has three backs at roughly 100 carries each—Damien Harris (126), Najee Harris (102) and Josh Jacobs (94)—and Etienne’s 176 carries lead a Clemson group that has also leaned on Tavien Feaster (71 carries), Adam Choice (68) and Lyn-J Dixon (56).

It’s a sign of the times, experts say. “It’s definitely been an evolution with regard to that position,” says Phil Savage, a longtime former NFL scout and executive who’s now the general manager of the Arizona Hotshots in the upstart Alliance of American Football. Most industry experts attribute this evolution to football’s philosophical shift from I-formations to spread offenses, but they also cite efforts to extend a running back’s career lifespan, which is the shortest of any position in professional football. “I know in pro football, you can still have a bell cow, but they’ve really tried to carve up the position because of the wear and tear and longevity,” Savage says. “In some ways, I think you may have a bit of a trickle-down effect as it relates to college teams.”

This isn’t completely new. Mike Alstott and Warrick Dunn’s Buccaneers teams popularized the approach 20 years ago, and Jim Taylor and Paul Hornung, with the Packers, did it as far back as the 1960s. But today, it is more commonplace than any other time in the sport’s history, college or pro. “Very few teams have one guy who’s the dude. If you do, it’s a Todd Gurley or a Saquon Barkley, someone who’s incredibly rare,” says Bleacher Report NFL draft analyst Matt Miller.

Etienne is very much familiar with this philosophy. He averaged 16 carries a game over the course of his career at Jennings High, a rarity for such a prized athlete at a small school that employs a triple-option attack. Why not use him more? Because his coaches wished to preserve their standout runner, and because he scored so often. Etienne changed the perception of the methodical split-back veer offense at Jennings. “The veer is three yards and a cloud of dust,” Estes says. “With Travis, it was 80 yards and the back of his feet.” Etienne found the end zone on every 6.7 attempts. “When he wanted to score,” says longtime Jennings head coach Rusty Phelps, “he scored.” Even when coaches didn’t immediately want him to score, he scored, like the time Jennings needed a long, time-consuming drive in the fourth quarter of a tied game. Etienne scored on its first play. There was the game in which the opposing team didn’t record a tackle on Etienne—“Seriously, it happened,” Estes says—and there was the interception that Etienne, playing spot duty at cornerback, returned for a 103-yard touchdown on his very first varsity defensive snap.

Etienne became such a sensation that the post-game handshake ritual turned into a receiving line. Players from the other team reached into their pants, removed their cell phones and snapped selfies with Etienne. College coaches didn’t give him as much attention, at times, as his own opponents. “I’d tell recruiters that if he was in New Orleans, he’d probably be the No. 1 recruit in the nation,” Phelps says.

Jennings is a town of 10,000 situated off I-10 between New Orleans and Houston, a place that rarely produces this kind of talent, with a high school that has fewer than 600 students. In 25 years at Jennings High, Phelps has coached two major college signees. Etienne had few big-time scholarship offers before he attended his first big recruiting camp in New Orleans in the spring of his junior year, beating out four- and five-stars around him with a 4.32-second 40-yard dash. “It hit Twitter and the phone rang off the hook,” Estes says, so much so that Phelps traded his flip phone for an iPhone. “After that, that same day,” Etienne says, “I had, like, five college schools calling me and offering me.”

Eighteen months into his stint at Clemson, Etienne is doing things no Tiger has ever done, like run for more than 650 yards in a four-game stretch or score three rushing touchdowns in three straight games. “I think you’ve got to consider him a Heisman candidate,” Miller says. “If there’s a running back in this CFP that you really want to pay attention to as a future NFL star, it’s got to be him.” Etienne describes this time as “surreal,” something he can’t quite wrap his mind around right now. “You dream of things like this, moments like this, but for it to be really happening to you,” he says, “it’s hard to explain it.” Most who know him well—his mom Donnetta, sister Danielle and coaches at both Clemson and Jennings—say Travis Etienne doesn’t know how good Travis Etienne is. He’s shielded from his talents by a humble approach and an adolescent attitude (he’s a practical joker and an avid prankster). “I realize that I’m good, but people mention me with some of the bests,” he says. “I don’t feel like I’ve gained that recognition and respect to be mentioned with them yet.”

Already, Etienne is accomplishing what at least two football-playing members of his family, James Lyons and Janzen Jackson, could not. The latter, a former five-star recruit who signed with Tennessee in 2009, is now on the second year of an 11-year prison sentence for strangling his mother’s boyfriend to death. “Of all the ones who went and didn’t make it, he wants to be the one who makes it,” says Travis’s mother, Donnetta. Donnetta raised four children, all of them athletes. Travis’s older sisters Shanea and Danielle Lyons won championships in basketball and track, and his youngest brother, Trevor Etienne, is a freshman running back at Jennings High. Trevor looks, talks and acts like his brother. He’s got tree-trunk legs like his brother, too, and if not for a broken leg in August, he would be on his way to claiming his brother’s school records. At Jennings High, Trevor is Travis’s Little Brother. “I got to live up to those standards,” Trevor says. “I don’t have a choice.”

If you want to know where Travis got his speed, just ask his brother. “From chasing my mom’s car down the street,” a smiling Trevor says. This is a not-so-subtle shot at his brother. Travis is a momma’s boy, and when Donnetta would leave for work little Travis would race out of the house after her car. His grandma, Cynthia Beverly, soon found the only way to placate the young boy was by handing him a football. A normal site at the Etienne home was a football-toting Travis climbing over, around and through furniture, his toddler brother following his every move while their parents were at work.

It’s crazy to think back to that time, says Danielle, now that her brother is excelling on a national stage. The transition to a place 10 hours away wasn’t always easy, and Etienne spent much of his first few months at Clemson on the phone with his mother. There were mountains and weather to get used to, and the change in time zone, too. There was no Cajun cuisine and no Popeye’s, a Louisiana-based fast food chain and Travis’s favorite eatery. Only recently did Travis stumble upon a Popeye’s, on the trip to North Carolina for the ACC championship game. He scarfed down his favorites—chicken tenders and chicken wings—and then opened a blowout win over Pitt by running for a 75-yard touchdown on the first play. In the stands, his father Travis Sr. leaned over to Donnetta: “That Popeye’s gave him wings.”

Etienne keeps his college freezer stocked with favorites his family brings him from back home: green beans, turkey necks, red beans, navy beans and, of course, boudin. The distance is difficult but has been made easier over time. Still, the question needs answering: Why didn’t Etienne just stay home? That’s complicated. LSU sits 90 minutes from Jennings, but during his senior season, the program underwent a head coaching change. Donnetta says former coach Les Miles and the previous staff made her field unappreciated for much of the recruiting process. The Tigers prioritized not Etienne but Cam Akers, a five star Mississippi tailback. LSU did not offer Etienne a scholarship until Akers committed to Florida State about six weeks before signing day, a transparent move that didn’t sit well with anyone. “They downplayed us,” Donnetta says.

The real challenger in Etienne’s recruiting process was Oregon. Etienne silently committed to the Oregon coaching staff, something he even hid from his mother, she says. The Ducks then underwent a coaching change as well, and a few weeks later, a new team that had not spent much time recruiting Etienne entered the picture: Clemson. Memphis-area running back Cordarrian Richardson decommitted in late December, resulting in the Tigers’ late pursuit of Etienne. Forty-five minutes after Clemson’s national championship game win over Alabama, Phelps received a call from Clemson running backs coach and co-offensive coordinator Tony Elliott. “Your running back still available?” Elliott asked. Phelps, so shocked by the call, thought he was being pranked. “I looked up his area code on the internet,” Phelps says, “and yep, it was South Carolina.”

Travis and Donnetta visited campus, loved it, and here he is now, two wins from a national championship. Donnetta is expecting more than 100 family members at the Cotton Bowl semifinal with Notre Dame on Dec. 29. It’s a short drive for many of them. Travis’s grandmother is one of 15 children, and much of the family resides in Houston and Dallas. How many carries he’ll get against the Irish will, of course, remain unknown until gametime, and maybe it doesn’t matter. Etienne has proven as much as anyone that he doesn’t need an exorbitant number of touches to be productive.

In fact, Estes kicks himself for not giving his former running back one more carry during his four-year high school career. In what the coach describes as the “worst play call of my life,” Jennings’s quarterback was stuffed on a sneak on fourth-and-goal from the one-yard line in an eventual season-ending loss in the playoffs. “Should have just given it to Travis,” Estes grumbles. “He would have scored.”