Inside the Nationwide, Fraternity-Like Bond of College Basketball Walk-Ons

Why Google a question perhaps the country’s greatest group text can instantaneously answer?

“Joey Smoke,” Rem Bakamus pinged all 16 numbers. “Is it your Senior Night?” Moments later, Joey Lane, the first preferred walk-on in the history of Ohio State basketball, responded, confirming the Buckeyes’ final home game of the season was Sunday, March 10.

“I’m going,” Jake Lorbach, a former OSU walk-on himself, declared. “I think I’m behind the bench. Probably making a sign.”

“Ya better be,” added Tod Lanter, a Kentucky walk-on from 2012–2015.

Sam Frayer, once an Ohio University walk-on now serving as a graduate assistant at Xavier, snapped a screenshot of Lane crying during one of the final on-camera interviews of his career. “Put this on a sign,” Frayer teased. “Love you Joey.”

Lane started for the first time in his four-year career during that weekend’s contest vs. Wisconsin, a tradition honored in many programs nationwide. He immediately launched a three-pointer during the game’s first possession. The cohort’s adjacent Snapchat whirred to life, firing videos equally roasting his miss and celebrating how it nearly found cotton. Lane and Jack Beach, a senior walk-on at Gonzaga who started and played two minutes in the Bulldogs’ own final home game vs. BYU, are the final active members of the nation’s greatest unsung collegiate brotherhood. America’s premier fraternity is not represented by three Greek letters. It telephonically bonds past and present Division I basketball walk-ons from around the country, who have formed conceivably the most unlikely family in sports. “Most of us haven’t even met each other,” says Wichita State’s JR Simon. “But we’ve all agreed we are best friends,” Lane says.

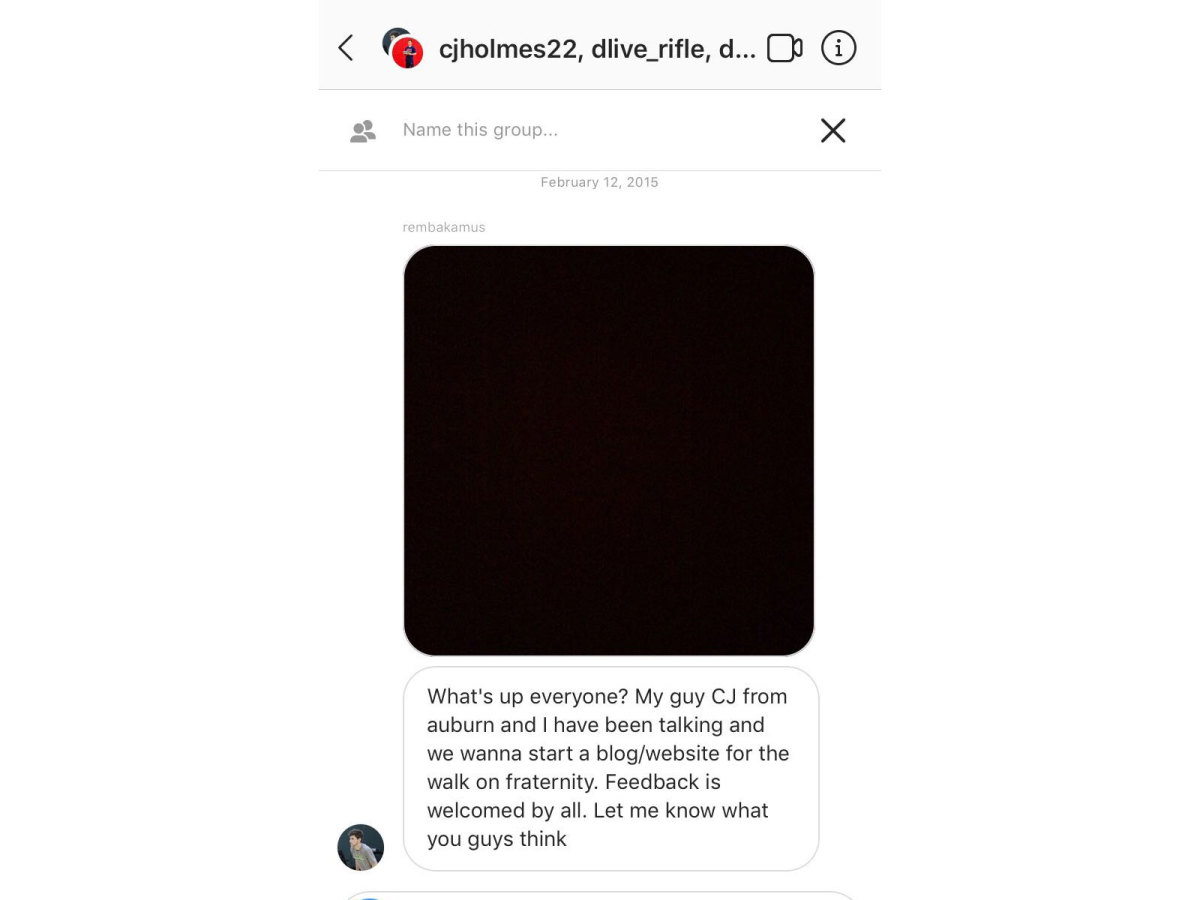

The “fraternity” originated in 2014, when Bakamus, then a walk-on at Gonzaga, and C.J. Holmes, a walk-on at Auburn somehow connected over Twitter. They incessantly direct messaged each other, commiserating about the lows and cheering the highs that naturally come with being the lowest player on a major collegiate program’s totem pole. The life of a walk-on can sometimes prove lonely, when the hours of practice sweat equity don’t equate to actual game minutes, despite each player harboring the talent to feasibly start at a mid-major school.

“I wanted to find a way to bring these guys together, under one roof, to share these stories,” Holmes says. The duo began following other walk-ons both on Twitter and Instagram. They would seek out rivals of their same stature during warmups, crossing half-court to exchange daps and news of their growing movement. Those new contacts spread the word to other walk-ons like wildfire. Bakamus eventually dispatched an Instagram message to over a dozen walk-ons, directing the fraternity-of-sorts to form a GroupMe. “A lot of people get tired of the stigma that comes with being a walk on,” says another former Gonzaga walk-on, Connor Griffin. “These guys have just done a great job embracing that and understanding there’s a bigger picture to it.”

“I just used it for relief,” Bakamus says. “Once we started exchanging stories, you’ve been there before, you can just relate to everybody in every way. We just ran with it.” The GroupMe ballooned to 60 members, spanning from the grandest of blue bloods to mid-major upstarts. “It started taking off,” Holmes says. “We just kept finding more dudes and more dudes,” says Zach Bush, another former Wichita State walk-on. “It was downhill from there,” cracks Arkansas’s Manny Watkins. The conversation devolved from daily hoop minutia to debating general sports conversations that dominated the national news cycle. Although a crop of 15 or so walk-ons quickly emerged as significantly active contributors compared to the majority of the group. “They didn’t want to deal with all the notifications,” Holmes explains. “Because these guys literally talk 24/7.”

The constant chatter sparked a smaller group iMessage, quaintly labeled “OG Walk-On Frat,” which has sustained through Lane’s senior night and very likely beyond—the last message of the original GroupMe was sent in March 2018. Hardly a day passes without a minimum of 30 alerts notifying each member of the fraternity. For the better part of this season, the group text has existed under a moniker simply boasting the goat emoji. They have playfully personified conference rivalries, like the occasions Lanter’s Wildcats faced Holmes’s Tigers. “When CJ came to Rupp, I put one in his eye,” Lanter brags.

They perused each other’s schedules, circling matchups featuring a high probability of a blowout, ripe for a few minutes of garbage time burn. Buckets, of course, are the main priority. “They know that when I go in, I’m shooting for sure,” Lane says. One game after the Zags slayed Duke in November, Beach drained a triple in seven minutes of action against North Dakota State. “When he scored, we went nuts,” Lane says. “We were begging him to shoot.” After one outing in which Frayer found the basket, he returned to find nearly 20 text messages awaiting in his locker. “These dudes were more happy than my actual friends,” he says. Their closest analog to hazing is having an on-court mistake forever captured on video and retweeted by the @walkonfrat account. They have mulled creating apparel similar to actual fraternities.

Yet in between dispensing micro-highlights, the group has offered an outlet for divulging girl problems and familial struggles. Cancer has misfortunately permeated many members’ closest relatives and friends. “It started as a goofy thing,” Bakamus says. “But as the years went on, relationships got strong, and now we really count on each other day-to-day.” After graduating from Gonzaga, Bakamus migrated south to serve as a graduate assistant at Baylor. The Bears, by some stroke of fate, visited Wichita State on Dec. 1, just days after Simon’s mother passed, having gone without oxygen for too long after breathing complications induced unconsciousness. Bakamus, however, doesn’t travel to all of Baylor’s road games, and so the fraternity members each venmoed increments of $15-$25 to cover the majority of his $400 flight from Texas to Kansas. “It’s easy to get things done with a group of us,” Lanter says. “You can count on these guys, whatever you need,” says Bush. “If you need space, if you need guys to talk to, if you just want to talk in general.”

Bakamus and Simon, now a GA at his alma mater, played in the fabled manager game the evening before Baylor and Wichita squared off. With the Bears having a free day following the matchup, Bakamus stayed in town, grabbing dinner with Simon and Bush, who also still resides in Wichita. The trio spent the next afternoon, a Sunday, watching football as if they’d been friends since middle school. The weekend truly marked the first in-person encounter between the former Shockers and their fraternity brother. “It was like we had been boys forever,” Bakamus says. They’re commonalities from the group message were amplified in reality. “If you lived here, we would be best friends,” Bush told Bakamus. “This is why we made this group. You’re so much like us.”

Joe Schwartz, a former walk-on at Texas, enlisted the help of the fraternity when his teammate and close friend Andrew Jones was diagnosed with leukemia last season. Schwartz cemented himself as an emotional backbone of the Longhorns’ program. “We all loved him,” says Brooklyn Nets center Jarrett Allen, who played one season at Texas. “He brought the same energy every day.” He translated that enthusiasm into philanthropy, annually raising tens of thousands of dollars to donate toys to a local children’s hospital. Schwartz had been organizing a charitable trick shot video, featuring walk-ons from around the country draining impossible heaves, hoping to spur funds for the Jimmy V foundation. After Jones learned his diagnosis, Schwartz shifted focus and geared his fundraising efforts to helping cover his point guard’s treatments. “We all assumed the worst when we first got the news,” he recalls. “Some of the pictures and FaceTimes that we got of him at his worst… they were bad.”

Schwartz ordered 10,000 wristbands with AJ1, signifying his teammates’ initials and number, emblazoned around each rubber circle. He handed out several thousand to spread awareness. Then, selling the bands for roughly $3 each, Schwartz trekked all over campus, emotions bubbling in his throat as he knocked on the doors of sorority houses and dorm buildings. Schwartz had pinpointed Texas’ massive Greek system as the prime donors for his campaign, but as he discussed the project within his own fraternity, venmo payments of varying amounts from students in Wichita and Spokane and Lexington began to flood his account. “We under-ordered,” Schwartz says. His endeavor ultimately generated $20,000 for Jones. “It’s like having a dozen brothers that all understand you,” Lorbach says.

The elder Ohio State walk-on’s compassion stems from his own family’s health struggles. Lorbach’s father has battled a bile duct and liver cancer for years. When he arrived in Columbus, Lorbach’s parents shouldered his student loans, yet treatments gradually made those monthly payments more and more difficult to muster. He persisted nonetheless, waving a towel as feverishly as any member of the Buckeyes’ bench. When D’Angelo Russell visited campus as a high-profile recruit, the coaching staff made sure to introduce him to Lorbach. Once the elite point guard prospect joined the program, he spent countless post-practice hours battling one-on-one against the walk-on.

They worked within a self-imposed three-dribble limit, a tactic Lorbach learned from a nearby trainer Robbie Haught, who still drills Russell every offseason. “I used to bust his ass,” the All-Star point guard now coos. Lorbach felt his game progress from those late-night sparring sessions, and experienced Russell’s palpable progression throughout his flashpan freshman campaign firsthand. When Ohio State visited Northwestern that winter, Russell’s dream season crescendoed in a career-high, 33-point drubbing of the Wildcats. “He was dicing up the defense and throwing some of the most ridiculous passes I’ve ever seen,” Lorbach says. With just under two minutes to play, Russell isolated a defender at the top of the key, rejected a screen and sent his opponent sputtering to the hardwood. “I dropped somebody,” Russell recalls, grinning.

At the Buckeyes’ next film session, then-head coach Thad Matta rolled the clip. “He kept showing me make the kid fall, kept showing me make the kid fall, kept showing me make the kid fall,” Russell says. “Every time I made the kid fall, Jake popped up.” In the top right corner of the screen, the floppy-haired walk-on burst off the bench like he was fired out of an ejector seat, frenetically sprinting up and down the sideline like he had witnessed an actual homicide. Matta zoomed in on Lorbach’s reaction, gushing over the emphatic display of team spirit. “I love that s---!” Matta professed. “I love that s--- so much, I’m putting you on scholarship.” “Jake just started crying,” Russell says. “They didn’t have to struggle to pay his dad’s medical bills anymore.”

When Schwartz’s Longhorns fell to Nevada in the first round of last March’s NCAA tournament, the walk-on could hardly process the finality of his playing days. His entire extended family had flocked to Nashville, expecting to witness Texas reach the Sweet 16. Yet when Schwartz retreated back to the team’s hotel, Lanter and Frayer were waiting in the hotel lobby, offering bear hugs before Schwartz was even consoled by his parents. “After such an awful ending to your career, it was pretty special,” he says. During Gonzaga’s run to the national championship game in 2017, Bakamus, one of that juggernaut’s seniors, and Beach, then a freshman, frequently snapchatted behind-the-scenes moments to the group, providing an inside look at the Final Four most of the fraternity could only dream of. “I felt like all those guys were my teammates, all those guys were a part of it with me,” Bakamus says. “Even if you haven’t met someone, if you talk to someone enough, you can still kind of see where their heart is,” Watkins adds. “All these guys, their hearts are in the right place.”

Beach and the Zags could return to the sport’s ultimate weekend this month, as the Bulldogs may still be in line for a No. 1 seed even after falling to Saint Mary’s in the West Coast Conference championship game on Tuesday. Lane and Ohio State may also be dancing should the Buckeyes emerge from the tournament’s bubble into March Madness’ field of 68. Regardless, only weeks separate the walk-on fraternity from its playing days and basketball mortality, despite the group messages’ prolific activity. “We all thought this thing was gonna die after we finished playing,” Schwartz says. “If anything, it’s gotten more amped up.”

Seven fraternity members hold posts on Division I coaching staffs. “It’s kind of become a GA frat,” Frayer jokes. Holmes covers Arizona for The Athletic. “Somebody might be on somebody’s coaching staff someday, somebody might be covering somebody,” Bakamus says. “You never know. It’s such a tight group. I’m expecting the majority of them to be making it to my wedding."

“I hope that one day, we all make it through and decide to make a staff and build a team together,” Lorbach says. March, of course, is known for its trademark madness. The cohesion of this motley crew of walk-ons may be the wildest turn of all.