The Vacation Town Where Nick Saban and Dabo Swinney Go to Disappear

Every Fourth of July, the citizens of Boca Grande, Fla., organize a golf cart parade. They decorate their carts with patriotic banners, flags and balloons, and the procession snakes its way through town. Some people bring speakers and blare music; others toss candy to the crowd of people lining the streets, cheering them on.

Last year, the Boca Beacon, the local newspaper, reported that about 120 golf carts participated in the parade. The paper ran a spread inside, on page 16, which included 10 pictures from the event. Buried in the lower-right corner, above an advertisement for a local plumber, was a picture of a man and his wife, smiling as they rode along in their cart. The woman wore a red-white-and-blue lei, and the man wore a furry hat and appeared to be holding a horn of some sort. They looked like any other couple in the parade. The newspaper made no mention that the man was the head coach at Clemson, Dabo Swinney.

One local woman thought she might have spotted Alabama coach Nick Saban along the parade route, too, cheering people on. If he were there, the newspaper made no mention of him, either.

In Swinney’s case, the Beacon’s editor, Marcy Shortuse, actually made a conscious decision not to identify him. She didn’t feel as though it were necessary. “It’s like, you see them in the grocery store,” Shortuse says. “You don’t see Nick as much as you see Dabo, but they’re around. They’re always around.”

Every year, independent of one another, Swinney and Saban vacation in the same tiny town, on a small island just off Florida's Gulf Coast, about 100 miles south of Tampa. The town is called Boca Grande, and it sits on Gasparilla Island, a strip of land that’s only seven miles long and, at its widest point, about one mile wide. Boca Grande’s population is only around 1,700, but that number swells during the high season, when hordes of affluent northerners arrive. Many of them own second homes there. They’re drawn to Boca Grande for its historic downtown, its pristine beaches and its world-class fishing. They find this little beach town quaint and charming—the island’s main mode of transportation is golf cart, after all.

But Boca Grande’s main allure is the attitude the locals have developed over the years, a culture they’ve created to accommodate the rich and famous. People know they can visit Boca Grande and not be bothered. They can attend a Fourth of July parade without making front-page news. Indeed, Boca Grande offers its visitors something you can’t put on a brochure, something that football coaches crave in the offseason especially: pure, unadulterated privacy.

“We would never dream of hounding them or making a scene,” says Wesley Locke, the executive director of the Boca Grande chamber of commerce. “They come here for the quiet.”

For generations, the island has been a gathering place for the wealthy elite. In the early 20th century, there was not much in Boca Grande, except for a railroad that brought in phosphate to be exported from the port at the south end of the island. In 1913, some locals opened a swanky resort, The Gasparilla Inn, to accommodate the number of people arriving on the train. Soon, the island became a destination for aristocrats from the north. The du Ponts, the Rockefellers, and the Vanderbilts are said to have spent time there. “Back in the day, you had to be on the social register to get a room at The Gasparilla Inn,” says Kim Kyle, the executive director of the Boca Grande historical society. “I guess, you had to be the ‘right’ people—wealthy people from certain classes and certain ethnic backgrounds.”

That kind of discrimination is now “long gone,” Kyle says. “Anyone that can afford to stay at The Gasparilla Inn is welcome.”

Not everyone can afford to, though. Over the years, as Boca Grande expanded, it continued to draw the rich and powerful, and that further cemented the island’s air of exclusivity. Boca Grande regulars have included President George H.W. Bush and his family; the actress Katharine Hepburn; and the other Busch family, of Budweiser fame. In recent years, locals have spotted Tom Brokaw, Chris O’Donnell, Tucker Carlson, Jason Garrett, and Bill Cowher out and about.

Swinney started coming around 1994, when he was a graduate assistant at Alabama, under Gene Stallings. Swinney kept returning to the island as he climbed the coaching ladder, and in 2010, after he’d been named head coach at Clemson, he finally got his own place in Boca Grande. A few years after that, Saban got a place there, too. The way Swinney and Saban describe it, this seemed to have been one big coincidence, that they both chose the same vacation spot. Soon enough, the two of them apparently started bumping into one another on the island. “Because of our schedules,” Saban said in 2017, “we end up there sometimes at the same time.”

When they’re both in Boca Grande, Swinney and Saban lead very different lives. Saban’s place is at the north end of the island, which is a quieter, more residential area. Swinney has a place near the south end, which is a bit livelier because it’s closer to the town’s shops and restaurants. Which makes sense: Swinney is the outgoing one, Saban the introvert.

Not that the downtown area gets too rowdy. There are no traffic lights, no chain stores, no tall buildings. The Gasparilla Island Conservation District Act of 1980 bans commercial franchises from the island, caps buildings at three stories tall, and outlaws billboards and exterior advertising. The legislation is meant to preserve Boca Grande’s charm. It makes the town feel as though it’s stuck in the 1950s.

One of the jewels of Boca Grande is The Temptation Restaurant, which has been a downtown staple since 1947. Locals simply call it The Temp, and it’s instantly recognizable by the martini glass on the neon sign out front. When Saban visits The Temp, he likes to sit in the original dining room, which has old wooden booths and dark lighting. Swinney likes to sit in the Caribbean room, which was added later when the restaurant expanded. It’s louder, more jovial and full of bright colors.

Like most restaurants on the island, The Temp has unwritten rules: Don’t bother famous customers. Don’t ask for selfies or autographs. Don’t start unwanted conversations. “That’s why they come [to Boca Grande],” says Kevin Stockdale, one of The Temp’s co-owners, “because nobody really bothers them.” But Swinney openly flaunts this rule. He’s willing to chat with pretty much anyone who approaches him. Saban? He’s one of the reasons the rule exists in the first place. “I’ve never seen anyone approach Saban,” says Jeff Simmons, another of The Temp’s owners. “He has that demeanor where it doesn’t look like a good idea.”

On the west side of the island, there’s a stretch of beach, and some days you can spot Swinney out on the water, on his 25-plus-foot pontoon boat. Generally, pontoon boats are better suited for hosting parties than for fishing, and Swinney’s apparently stands out from the rest. “It’s decked out; there’s some money in that boat,” says Rob Hayes, a fourth-generation Boca Grande fishing captain. “It has all the bells and whistles and then some.”

Saban apparently has a boat on the island, too, but he uses his to fish. People flock to Boca Grande each year for its fishing, particularly for tarpon, a trophy fish that can grow as long as a person is tall. Boca Grande is known as the tarpon capital of the world. Every year, from April through August, tarpon run through Boca Grande Pass, at the southern part of the island. There are tarpon everywhere around town: on murals, on logos, on sculptures. Boca Grande hosts several tarpon tournaments and has a number of fishing guides who will take you out to catch one. In May 2015, at an SEC media event, Saban bragged that the day before he had caught five tarpon in about an hour. One of them had given him a particularly big fight; it was six feet long and 180 pounds. “I hung in there,” Saban said. “It’s called mental toughness.” He had caught the fish off Boca Grande.

SI contacted the fishing guide who takes Saban fishing regularly. Out of respect for Saban and the island’s culture of silence, he declined to comment. He feared that if he talked, Saban would never fish with him again.

Details about Swinney’s island life are not much easier to come by. Paula Beecher has become friendly with Swinney and his wife over the years. They often come into Sisters, the restaurant Beecher and her sister own together. Beecher says, for the last few years at least, the Swinneys have thrown a Fourth of July party on the island. They hire a taco truck and an ice cream truck, and set up a karaoke machine. That invites the question: How is Dabo as a karaoke singer? Now Beecher clams up, perhaps realizing that she’s shared too much. “Uhhh, he’s so cool,” she answers. “He and Kathleen are both awesome. They’re great."

From time to time, Swinney and Saban will actually rendezvous with one another on the island. They’ve mentioned these meet-ups over the years, without going too far in depth. They apparently golf together, take boat rides, have dinner. Through all that, they seem to have developed a real friendship. “This situation sort of offers us the opportunity to get together sometimes and talk about things,” Saban said in 2017. “And we do that a lot.”

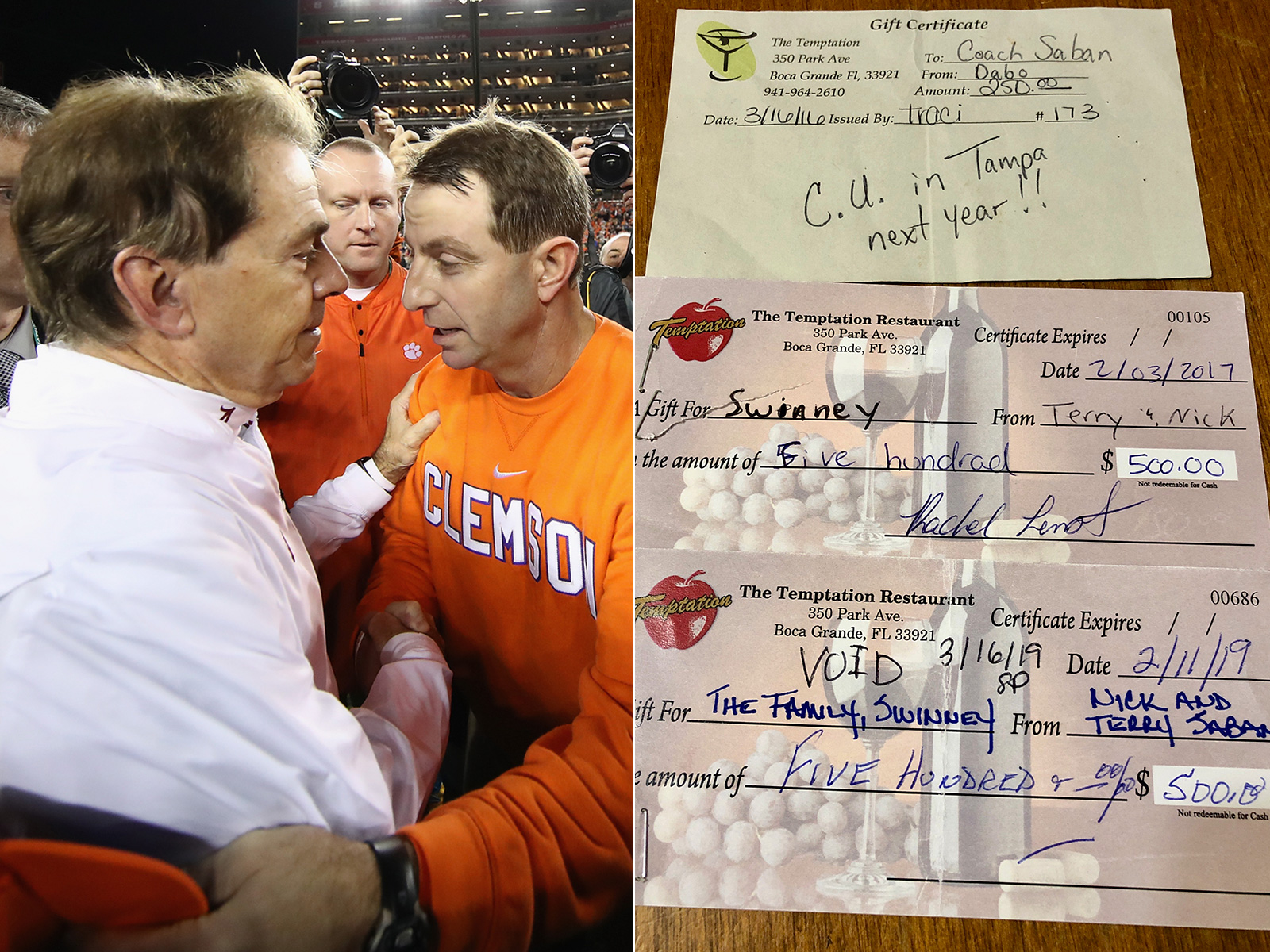

These get-togethers took on a different meaning once Saban’s and Swinney’s schools became rivals on the field. It so happened that, shortly after Saban got his place in Boca Grande, Swinney built Clemson into a perennial contender. For three of the last four years now, Alabama and Clemson have played for the national title. Before the first meeting, in 2016, Swinney and Saban made a friendly wager: the loser had to buy the winner dinner at The Temp. After Clemson lost, Swinney bought Saban a $250 gift certificate to the restaurant. He wrote at the bottom: “C. U. in Tampa next year!!” referencing the site of the next championship. The following year, as Swinney predicted, the teams had a rematch in Tampa. This time, Swinney won, and Saban bought him a $500 gift certificate to The Temp.

The third meeting was this past January. Clemson thrashed Alabama 44–16, and afterward, Saban gave Swinney another $500 gift certificate. In mid-March, Swinney brought his family to The Temp to redeem his prize. After Swinney finished his meal, Kevin Stockdale, The Temp’s co-owner, came over to check on him. “He goes, ‘Kevin, that was the best meal I’ve ever had,’ ” Stockdale recalls. “Of course, it’s because it was on Nick Saban’s dime!”