The Franks Connection: How a Brothers' Bond Aided the Breakthrough Florida's QB Needed

Among the Franks brothers’ chores while living on a 12-acre slice of the Florida panhandle, dragging the pasture to clear horse manure was by far the worst. But they did it, because if they didn’t, they’d have to weave between piles of dung while playing football. And that’s no way to play football.

Jordan and Feleipe Franks have been mostly inseparable their entire lives. As children, they’d wake up for school by 4:30 a.m. to start their morning routine: feed the horses, scoop their poop, clear hay bales and, in the most literal sense, mend fences. After the chores, they’d make the 30-minute commute to school from the family’s swampy, wooded land in Wakulla County, a rural region south of Tallahassee. Jordan refers to his home as “the boondocks,” and it’s easy to see why. Three-fourths of Wakulla County is state or national park land, and its largest municipality is a place called Sopchoppy. This is where Jordan and Feleipe grew up, doing mostly everything together, and that includes football. Despite their two-year age gap, Jordan, a receiver, and little brother Feleipe, a quarterback, formed one of the most fruitful connections in the history of the Wakulla High School War Eagles football program. A touchdown strike in their home stadium would often trigger the public address announcer to boom, “The Franks Connection!”

The Franks Connection ended there, in 2013, short of realizing a dream: playing as brothers for the University of Florida. Jordan, not blessed with his brother’s 6-foot-6 frame, knew the dream would never be realized when, on a visit to Gainesville in June 2013, he and Feleipe sat across from then-UF coach Will Muschamp, who delivered a separate message to each. We’re going to keep recruiting you, he told Jordan. He turned to Feleipe: We’re going to offer you a scholarship. “He was in ninth grade. I was a senior. I was mad and upset,” Jordan says in a recent interview. “I mean, I was happy for him, but Florida was our dream school. For the longest time, Feleipe said, ‘I’m not going to Florida because they didn’t offer you.’”

Five years later, who would have guessed that the Franks Connection would, in a way, reunite to help save a once-lost Gators football season and revive a downtrodden quarterback. During a time when his own fans booed him, when his team slumped into a skid, when his coach sent him to the bench, Feleipe connected with Jordan off the field—phone calls and text exchanged—in order to uplift his sprits and production on it. And it worked. “That’s always been the guy,” Feleipe says. “If something bad is going on in my life, he’s the guy I turn to talk to. That’s my rock, who I lean on. He’s always the first one there to have my back.”

And so, as the 2019 college football season finally arrives, one-half of the Franks Connection gets to kick off the 150th year of the sport. Florida versus Miami is the starting blocks for this four month-long sprint—it’ll be over before you know it—set in a neutral site environment in the state they both occupy, a monumental game between two rivals. But don’t just take our word for it.

“It’s huge,” says Gators coach Dan Mullen. This one is dripping with drama. No. 8 Florida is a touchdown favorite against a program it’s beaten just once in the last eight tries. This isn’t some annual duel, so you’ve got to ingest every last particle each time it rolls around (the teams last met in 2013 and are playing for just a seventh time since the 1980s, though they recently agreed to a home-and-home in 2024 and '25). As is the case with these in-state duels, the rosters include former high school teammates and kids from bordering towns. Their head coaches are even closely connected. Miami’s Manny Diaz worked as Mullen’s defensive coordinator at Mississippi State in separate one-season stints, 2010 and 2015. Pupil and defensive whiz, in his very first game as a head coach, meets teacher and offensive guru, in the beginning of his hotly billed second season.

In charge of executing Mullen’s game plan is a 6-foot-6, 225-pounder who 21 games into his college career finally emerged as the talent so many projected him to be during his high school days. Feleipe Franks ended his redshirt sophomore season with four straight victories, beginning with a 35–31 comeback win over South Carolina on Nov. 10 and ending with a 41–15 drubbing of Michigan in the Peach Bowl. During the stretch, he led an offense that averaged 45 points, showing off both that rifle arm (862 yards passing and eight touchdowns) and those long legs (177 yards rushing and four scores).

Somewhere in an NFL city watching on TV was his brother. Jordan Franks was a rookie tight end for the Bengals last year and remains on the team. He got the lesser end of his family’s athletic genes. At 6'4", 240 pounds, he’s sizable, but he’s not especially fast, he admits during an interview from Bengals training camp earlier this month. He’s missing that rocket arm his brother possesses and those long strides, too. His college career at UCF included him playing four positions: linebacker, defensive back, receiver and, finally for his last two seasons, tight end. He finished with 43 catches for 509 yards and two touchdowns, a stat line that left him undrafted. He made Cincinnati’s practice squad last summer, moved up to the active roster after a wave of injuries and actually caught two passes.

Jordan is the longshot of the Franks Connection, the darkhorse of the duo. He emerged from Wakulla High as a two-star prospect. Among the high school seniors in the 2014 recruiting class, Jordan was ranked No. 2,444. He had zero FBS offers up until the final week before signing day, when the Knights extended a deal. “He’s the underdog story,” says Feleipe. “He’s always been the underdog in his life.” And he’s now competing to retain his spot in the franchise. Jordan has no guarantees. He can be cut at any point. Each day, it’s live or die. Meanwhile, his brother has his choice of two sports. The Red Sox drafted Feleipe in the 31st round in June after he wowed team executives during an audition. He zipped a fastball over the plate at 95 mph. Feleipe hadn’t played baseball in four years. “He’s a big athletic freak,” deadpans Jordan.

Baseball is Plan B for Feleipe. Plan A was on life support just nine months ago. Amid his third season at UF and the second as the starter, the five-star product who, at one point, was the top-ranked dual-threat quarterback in the 2016 class, was swallowed up by the monster that is playing quarterback at the University of Florida. If Feleipe ever forgot about the Gators’ legacy at that position, he could march down to the west side of Ben Hill Griffin Stadium, where he’ll find three life-sized statues of UF’s Heisman Trophy-winning quarterbacks. Things boiled over during a 21-point home loss against Missouri. Franks followed a 105-yard performance in a loss to rival Georgia the week before with a 9-for-22 mark against the Tigers. During the game, the home crowd booed him multiple times and later, backup Kyle Trask replaced him to a roaring cheer.

Feleipe was humiliated. He was demoralized. He was frustrated. He’d ask himself internal questions. When is the production going to start coming? When are the stats going to equal the work I put in? On social media, he received nasty messages. His confidence was shot. He slipped “far down” the hole, he said, far enough that he required help from the most influential person in his life. “I told him, first of all, delete your Instagram because you’re going to check it if you have it,” Jordan says. “Coming from a small county, you know everybody. If you’re winning at the high school in the small county, everybody praises you. If you lose, everybody picks you up. On that scale in college, they boo you. I don’t think anybody is ready for getting booed.”

Between text messages and phone calls, the Franks brothers constantly communicated the week following the Missouri game. While Jordan prepared to play the Saints, Feleipe found himself battling Trask in what was an in-season quarterback competition ahead of the game against South Carolina. Fate intervened. While executing a trick play that Wednesday in practice—a quarterback-throwback—Trask fractured his foot, a season-ending injury. Feleipe stepped through the door of opportunity, this time wearing metaphorical earplugs. “Don’t go by what people say—they’re in the stands for a reason,” Jordan remembers telling his brother that week. “They don’t know what the hell they’re talking about.”

That Saturday, Feleipe and the Gators scored 21 unanswered points to beat the Gamecocks, in a game that included a rarity: a quarterback shushing his home crowd, Feleipe’s index finger pointed towards the sky and placed in front of his facemask (he later apologized for the gesture). Three weeks later, following a thumping of Florida State, he was the toast of Gainesville. From bad to good in just a couple weeks’ time? “One thing I can say, not many quarterbacks go through that period of time that quickly,” he says. There is a football explanation to Feleipe’s rise. “A light came on that 'I’m 6'6", 245 pounds and pretty athletic,’” Mullen explained. “If they’re going to completely empty the middle of the field and I can run into the end zone from 20 years away untouched, I can do that.” In those final four games, Feleipe carried the ball a career-high 16 times against the Gamecocks, 12 more times in the win over Florida State and 14 times for a career-high 74 yards against Michigan. But Mullen knows there is more to it than Xs and Os. “I think he started to block out all of the outside noise,” he said, “all of the other opinions.”

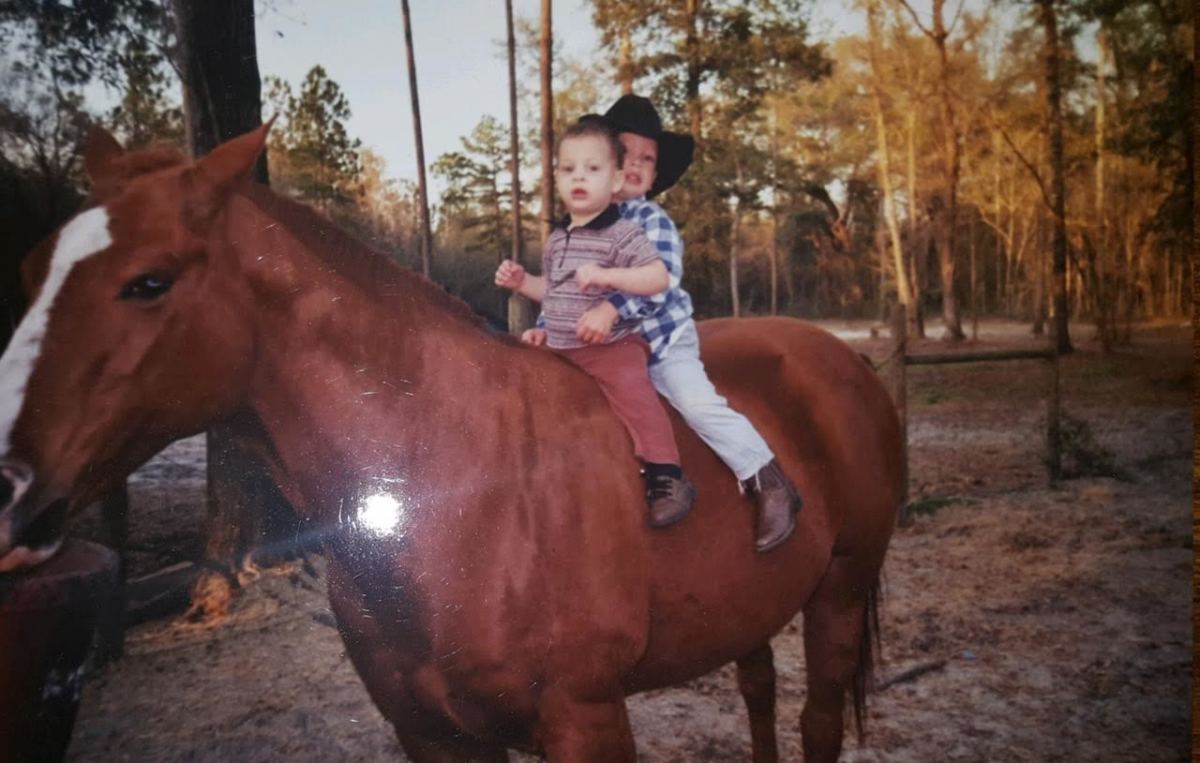

Jordan gets an assist with that. The Franks brothers built each other into what they are today, each driven by the other. Jordan was galvanized by his brother’s talents, and Feleipe was consumed by his brother’s work ethic. “They’d go to practice, come home and they’d go back out to the pasture and practice,” says their mother Ginger. They did more on the pasture than play football and scoop poop. They drove dirt bikes and four-wheelers, and they rode atop horses around the family’s backyard, which was a swamp fraught with gators, Jordan says. Their mother is a longtime employee for the state of Florida, born and raised near Melbourne. Their father, Don, is in the military and is scheduled to retire soon. Don comes from a Cajun background, growing up on the Texas-Louisiana border in Orange, Texas. During their sons’ younger years, the Franks used to travel across states to listen to zydeco bands. In fact, Don is behind his youngest son’s unique first name. Felipe is the Spanish variant of the name Philip, only that’s not what Ginger wrote on the birth certificate. “I spelled it wrong,” she says. It all worked out. Feleipe eventually earned a laundry list of nicknames. There is Flip Flop, Frap and, the most interesting of them all, Pee. The latter is rooted in Jordan’s inability as a child to pronounce his younger brother’s name. “And Feleipe couldn’t say Jordan,” Ginger says, “so he’d call him Joe Joe.”

Ginger is sometimes amazed when dwelling on her sons’ careers—one in the NFL and the other the starting quarterback for the home-state Gators. It’s not easy to see both play live. Last year, she caught a couple of Jordan’s games and most of Feleipe’s, driving her 2013 Toyota Prius so much that’s she’s barreled through the 200,000-mile mark. Her sons don’t often watch each other live either. Jordan has seen Feleipe play once in person, and it was a doozy. He witnessed his brother, then a redshirt freshman, complete a 63-yard Hail Mary pass to beat Tennessee in 2017. Feleipe is scheduled to watch his brother play for the first time when the Bengals meet the Dolphins in Miami on Dec. 22, his birthday.

Maybe Feleipe won’t be there. Maybe he’ll be too busy preparing for a trip to the playoff. Many have the Gators as a top-10 team in preseason polls, but they’ll have to maneuver through a prickly schedule, with home games against Auburn and Florida State and road or neutral site games against LSU, South Carolina, Georgia and, coming up this Saturday, Miami. It’s no easy road for Florida and its tall, lanky quarterback. But then again, the road here wasn’t easy either, punctuated by rejections and denials, boos and benchings. In the craziest chapter of them all, a guy Florida didn’t want helped a guy Florida had. Jordan Franks always thought he’d receive a courtesy scholarship offer from the Gators, meant to convince his brother to choose UF. It never came. “It’s funny now that I look back at it,” he laughs. “It’s funny.” Why so funny? Because, years down the line, the Franks Connection aided the Gators after all.