Behind the Scenes as SEC Refs Get a Unique Primer at Georgia Camp

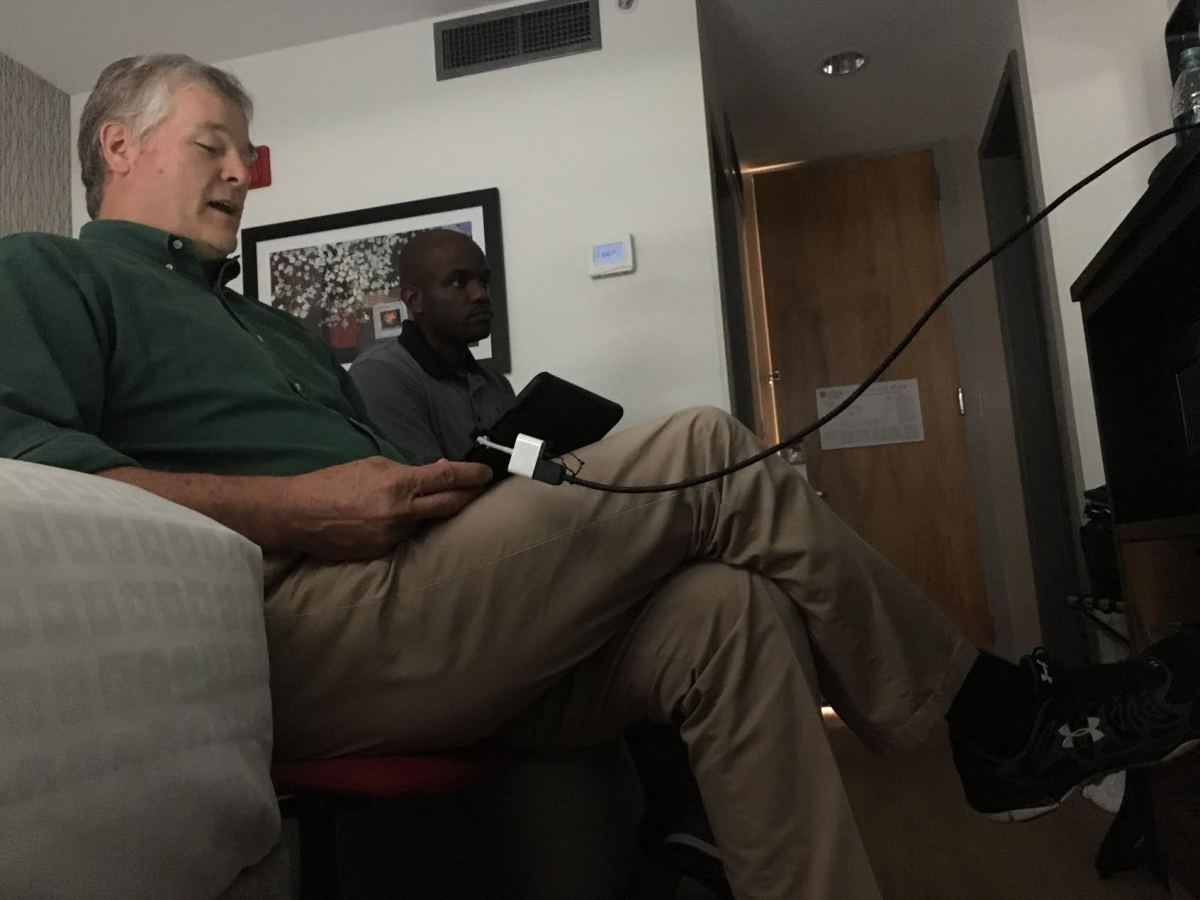

ATHENS, Ga. — On this Friday afternoon in August, Room 240 at the University of Georgia Hotel is host to a spirited debate among three Southeastern Conference game officials. Playing on the TV screen is a mostly unremarkable interior rushing play in a game last season between Missouri and UT-Martin, where the UT-Martin center appears to commit a holding foul. Or is it a hold? Russ Pulley, a 60-year-old former FBI agent and 18-year SEC officiating veteran, puts the play into question. The older wise man is challenging the two younger refs on either side of him. It becomes clear he knows something they don’t.

Pulley swipes his finger across an iPad connected to the TV to replay the clip. The center pulls the defensive lineman to the ground, both of them toppling to the turf in a surefire sign of holding. That settles it—it’s a hold. Pulley swipes a third time and, hmm, maybe it’s not a hold after all. The defensive lineman, not the center, appears to carry the two toward the Earth. Pulley swipes again. Yes, it’s a hold. Swipe. No, it’s not a hold. Swipe. Yes. Swipe. No. Swipe. “Wait!” Pulley exclaims. “Look at the defender’s foot.” And there on the screen is something only the sage has seen: The defensive lineman was not pulled to the ground—he tripped, stumbling over the leg of the offensive guard and then carrying the center with him to the turf. “I can’t tell you,” Pulley says, “how often I see guys call that holding.”

Pulley and his two younger pupils, Ted Pitts and Walter Flowers, might be officials in the country’s premier conference, but just like college football fans, they too argue about holding. They debate pass interference also, and chop blocks and targeting. Officiating is not an exact science, even with video replays and still-shot images. Partly because of that technology, officials are under more scrutiny than ever. Replay, while progressive, calls attention to human error. Additional safety rules, while necessary, expand the rulebook, and the escalating speed of the game, while entertaining, can exacerbate problems. It’s never been a more challenging time to be an official, particularly one working in one of the most passionately hostile sectors in all of sports, SEC football. “We leave a stadium and everybody is either happy with you or mad with you,” Florida coach Dan Mullen says. “I don’t think anybody is happy at those guys when they leave a stadium.”

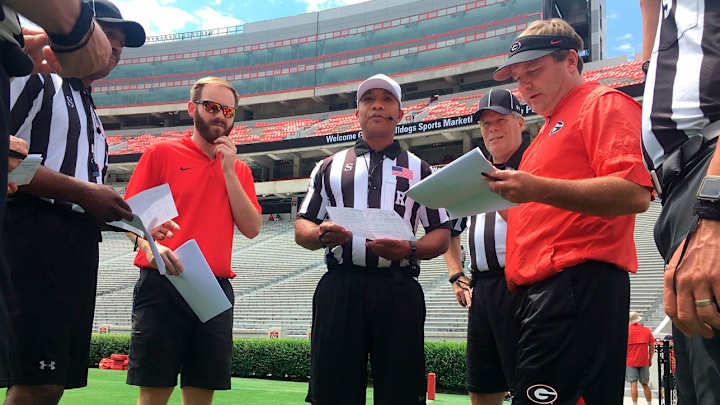

The SEC and the University of Georgia allowed Sports Illustrated behind the scenes access to one of the league’s new endeavors this year: embedding game officials in football camps around the conference. For two days at this particular camp at UGA, an officiating crew attended team gatherings, mingled with head coach Kirby Smart during practice, sat amid players while listening to a motivational speaker, socialized with strength coaches in the weight room, dined next to guys like quarterback Jake Fromm and, when given a break while players studied film, the officials huddled in their hotel room to examine a different kind of tape. Here’s an inside look at how officials prepare for this college football season in one of the more unique ways—with the team itself.

The University of Georgia Hotel is less than a half-mile from Sanford Stadium and a mile from Athens’ buzzing downtown entertainment district. During the first two weeks of August each year, the hotel is home base for the Georgia football team’s preseason camp. It is overrun with players and staff members, its rooms transformed into college dormitories and its most opulent ballroom turned into a dining hall. It is here, in the Magnolia Room, as hotel staff ready a lavish lunch buffet, that eight SEC game officials gather at a dining table for their very first crew meeting of 2019.

The SEC employs nine crews of eight officials each, along with a handful of alternates. Crews work together through the course of the regular season and can sometimes remain intact for multiple years. Each crew has a chief. That man is always the head referee or, in their own lingo, the white hat. The white hat in this particular crew is James Carter, a 51-year-old father of two from Alabama and one of two black head referees in the conference. Carter’s crew this year includes three new members, two of them rookies. This meeting is similar to a football team’s first gathering before camp. Expectations are communicated, ground rules are discussed and introductions are made. Carter formally welcomes the three newbies to the group with a clear message. “We’ve got to be a team,” he says. “It’s important. We have three new members of this team. We’re excited to have you, and I’m not just blowing smoke up your ass.”

Carter’s group is pretty diverse. One each is from Tennessee (Pulley), Alabama (Carter), Arkansas (Dax Hill), South Carolina (Pitts, a rookie) and Texas (Glenn Fucik). Three are from Georgia (Johnny Crawford, Flowers, new to the crew, and Jonathan Middlebrooks, the other rookie). They range in age from Flowers at 38 to Crawford at 61. And being a rookie doesn’t mean you’re necessarily young; Middlebrooks is 53. For college refs, officiating is a part-time job. Two of the eight are retired and three are educators. There is an insurance salesman, an accountant and an elected city official. Just like most groups in the melting pot of America, there is a cultural divide among them. For example, some of the members hum along to 1990s R&B playing over the ballroom’s ceiling speakers. And some do not. “Bone Thugs-N-Harmony,” Carter says, swaying to the music and singing along. Crawford gazes across the table at his younger crew chief, “Who?”

For many of these guys, reaching this point in their career is the peak. “Been officiating 20 years,” says Pitts, the 47-year-old rookie and former state Congressman in South Carolina. “The goal was always to get to the SEC.” Some of them want even more. Fucik is one of 42 officials in the NFL’s Official Development Program and has been invited to ref XFL games this coming spring. Last year was Fucik’s first in the SEC, and Pulley still refers to the 42-year old by a flattering nickname: Super Rookie. They have all reached this level in similar fashion—fighting their way through the minor leagues while making little money. Fucik spent eight years in Conference USA, and Middlebrooks went from the SIAC to the Southern to the Sun Belt. While an official in the SIAC, Middlebrooks made $175 a game, with no travel expenses (SEC pays its officials $2,500 a game plus expenses; some veteran NFL refs make more than $10,000 a game). These guys can be sent back to the minor leagues in a variety of ways, most notably for their performance in a season-long grading system. However, they also must endure a yearly, three-day July boot camp in Birmingham, where they must pass a written test and run 1.5 miles in a designated time based on their age.

No one wants drop back down to the minors (usually the Sun Belt). Early in his career, Pitts slept in his car between games he officiated, and Pulley used to drive two hours across Tennessee to call a middle school game just to practice his craft. They have all sacrificed time with their families (seven of the eight have at least two children), and some have even abandoned full-time professions. To free up weekends for officiating, Fucik went from heading security for Target to becoming a PE coach. In one of the more extreme examples, Pulley picked the SEC over the FBI. He chose in 2002 to end his 18-year stint with the bureau after supervisors offered him an ultimatum: us or them. Pulley even hired a lawyer to fight the FBI in a process that lasted nine months. “It’s the FBI,” laughs Pulley. “You don’t win that one.” Pulley and Fucik are second-generation officials. Daniel Russell Pulley Jr. umpired college baseball games. He wanted his son, Russ, to attend umpire school. “I spurned that idea,” Russ Pulley says. “The irony is I ended up leaving the job I wanted, the FBI, for officiating.”

Pulley is now in Year 18 in the SEC, and Crawford is in Year 19. These retirees anchor a crew that has drawn one of the tougher assignments almost annually. They’ve worked at least three of the last four Egg Bowls, the rivalry duel pitting Mississippi State and Ole Miss, including the one last season that produced an on-field brawl. This crew is a good one judging by their distinguished postseason assignments. Crews are split up for bowl season. Their individual regular-season grades—they are evaluated each week—determine their postseason assignments, if any. The old guys, Pulley and Crawford, worked Clemson’s trouncing over Notre Dame in the CFP semifinal in Dallas, and Fucik, in his rookie year, worked the SEC championship game. Grizzly vets like Crawford and Pulley have called some of the SEC’s most significant games this century. Crawford reffed the Cam-back, Auburn’s Cam Newton-led, 24-point comeback in the 2010 Iron Bowl en route to the Tigers’ national title. In his second year as a full-time SEC official in 2003, Pulley called LSU’s 17–14 win over Eli Manning and Ole Miss in Oxford, a victory that eventually led to Nick Saban’s first championship.

Back at the crew meeting in the makeshift Georgia dining hall, another ditty is blaring over the speakers, this time the smash hit The Real Slim Shady. Carter looks to Crawford. “That’s Eminem,” he says. Crawford’s face wrinkles and his mouth opens with a response that sends everyone chuckling. “M&Ms?”

On this Friday in August, Georgia offensive linemen are settling into their position meeting room for an hour-long film session with O-line coach Sam Pittman when two men, clearly not Georgia offensive linemen, walk through the doorway. Russ Pulley and Ted Pitts stride past Pittman, climb the rows of leather seats and situate themselves in the very back. They are here to observe—until Pittman pauses a clip of an extra-point play filmed at the previous day’s practice and while circling one of his lineman with a laser pointer, screams out to the officials, “Guys in the back! That O.K.? Or is that a hold?!” Pulley chimes in with the answer (it’s not a hold) and the meeting marches on.

This is Pulley’s realm. He refers to linemen as “my hogs,” because he feels a certain connection to them. He’s in the thick of things with them every game as an umpire, maybe the most perilous officiating position in football, stationed about five yards off the line of scrimmage, just behind the linebackers. The NFL thought the position so dangerous that years ago they moved the umpire to the offensive backfield, opposite the referee. College football toyed with the idea before leaving the umpire in its original position and adding a new official opposite the referee in the backfield, the center judge, which Pitts will man in 2019. Pulley, Pitts and James Carter, the referee, are considered interior officials, responsible for action in the box, which of course means that their flags are thrown mostly for the call of all calls: holding. No foul is called more in a given game than the hold. Along with pass interference, it is the most hotly debated of the fouls, and technology has exacerbated the criticism. Holding is not a reviewable foul. “Fans say, ‘How can they miss that!’” Carter says. “Well, we get one shot at it. You’re looking at it 15 times in slow-mo.”

Like every head referee, Carter takes the brunt of the criticism among his crew. He is the one on screen signaling the fouls even if he didn’t make the calls. Fans have no problem shooting the messenger. Memes of Carter exist online. Jokes are made about his muscly physique. Carter isn’t ashamed to show off the guns, a trend nowadays with officials that dates back to the notorious bulging biceps of NFL referee Ed Hochuli. While officiating the 2017 Quick Lane Bowl, Carter made a headline on the popular college football site SBNation. “Hello, this ref in NIU-Duke is college football’s newest BEEF REF,” it read. Carter isn’t on social media, but his sons are. They’ve shown him. “I cracked up when I saw,” he laughs.

Not all of the criticism is this lighthearted. Social media can be cruel. The incessant harassment is part of the reason there exists in America what SEC coordinator of officials Steve Shaw says is an “officiating crisis.” There is a shortage of officials, so far impacting only the lower rung of football (high schools and small colleges), but the trend will eventually make its way here. “Because of this whole social media aspect and the perception of how negative it is, it’s impacting us,” Shaw says. “The average age of people coming in to officiate at the high school level is much higher than it used to be. They say, ‘I don’t want to be a part of this.’” Social media backlash has inspired change in the SEC as it relates to officiating. The conference spent thousands on an independent review of its officiating conducted by Deloitte, an international accounting firm. The league also this year plans to publicly address officiating calls through a Twitter account, @SECOfficiating, and the SEC Network has hired former head referee Matt Austin to work as an officiating expert, providing viewers with deeper explanations of fouls. Viewers aren’t the only ones who need help with rules. Crawford believes that major college teams will soon begin hiring officials as full-time consultants. Already, some NFL teams have dipped into that water. The Buccaneers just hired veteran NFL official Larry Rose. “You know,” Crawford says, “it’s coming.”

On the field, officials let criticism roll off their proverbial backs. While patrolling the goal line as a side judge in a game last year, Glenn Fucik was the target of a flying bourbon bottle hurled his way from the student section. It missed. The scorn doesn’t always emanate from the student section. In one of the very first SEC games that he officiated, Fucik withheld a flag during a tight matchup between an Alabama cornerback and Tennessee receiver fighting for a deep pass. After the game, he retrieved his cell phone to find video from the TV broadcast, sent to him by friends and family, of former CBS play-by-play man Verne Lundquist harshly criticizing the no-call, even mentioning Fucik by name. Fucik still stands by that call—he didn’t see enough to warrant a flag. Most officials, especially Carter’s crew, take a more tolerant approach to calling fouls. Others aren’t so lax. Crews try to avoid quick trigger fingers. Fouls committed far away from the ball with no impact on the play are sometimes overlooked, Pulley and Pitts say. “We want to get out of there without anyone knowing we were there,” Pitts says. A cardinal sin for any official is the dreaded phantom call. In this industry, no one wants something they refer to as a WAG. What’s a WAG? Wild Ass Guess. During his entire career, Pulley has one regretful decision: a blocking below the waist penalty he called against a Georgia lineman. He should have never thrown that flag. “It was horses---,” he says, still troubled by the mistake more than a decade later.

Back in UGA’s offensive line meeting room, Pitts is seated in that back row silently listening as Pittman teaches his linemen, potentially the very same players Pitts might flag later this season. It is a weird blend of ref and player, but no one seems to mind. In fact, there is jesting between the two groups. After the O-line meeting, players head out to practice in the 100-degree heat, running in full gear past Carter’s crew members, many of them nibbling on snacks within the air conditioned confines of UGA’s football facility. “Hey,” says one smiling player, “you guys going to officiate or just stand around eating?”

On this Saturday, the officials are getting a treat. Their dressing area is the Georgia coaching staff’s swanky locker room. On a normal game day, the officials’ locker room is a small, unexceptional room on the other side of Sanford Stadium. Ahead of Saturday’s scrimmage, they’re nestled in this spacious, renovated suite, and in each of their lockers is a gift: a white Georgia baseball cap so new that it is still encased in the factory’s plastic wrapping. The officials know they can never wear this hat. They’ll give it away to family or friends, or just leave it in the locker.

Objectivity is essential to an official’s job. In every walk of life, they must appear impartial, detached from the normalcies of the casual college football fan. No rooting for teams and no donning team apparel. Russ Pulley takes things to the extreme: He won’t even wear clothing emblazoned with “SEC” as not to draw attention, and he’s not been in a casino for years, too risky with the recent legalization of sports gambling. Most officials do not operate social media accounts, but Pulley has no choice—he has to have a Twitter page. After all, he’s a Nashville Metro Council member, recently winning re-election earlier this month unopposed. With the rise of sports gambling, Pulley says the league audits each official’s social media platforms. Johnny Crawford doesn’t dabble in social media, but one of his daughters has a habit of responding to those critical of her father on Facebook. “I have to sometimes remind her,” he says.

Each official is given two tickets to every game they officiate. Those they bring to the game—wife, children, friends—must not wear team colors. Often times, they dress in black. Years ago, Pulley recalls a South Carolina-Tennessee game that ended controversially. During their post-game sprint from the field to the awaiting shuttle, one official hugged an orange-clad Tennessee fan. That was the rumor anyhow. Word reached then-SEC commissioner Mike Slive. “Find out who it is,” Slive notoriously said, “and fire him.” There are times on game days when officials bump into friends, but they cannot be seen fraternizing with those decked in LSU gold or Florida blue. “You just got be rude to them and move on,” Pulley says.

The SEC goes to great lengths to avoid the perception of bias. The league’s conflict of interest policy recently expanded this year. An SEC official cannot work a game that involves a school from which he/she graduated or spent significant time, where an official’s spouse or children attend, where there is a relative on the coaching staff or where the official has a business relationship. Most officials have at least once “scratched” team. This particular crew does not work Alabama games as its chief, Carter, is scratched from officiating the Tide. His son attended UA. Since Carter’s son has already graduated from Alabama, this is a voluntary scratch. He does this for perception’s sake. After all, Carter lives in Birmingham. Tim Flowers does not work Tennessee games, as his wife graduated from UT. Dax Hill can’t ref games involving Arkansas, as his daughter studies there, and Pitts is unable to officiate both South Carolina and Clemson games because he considers his role with the South Carolina Chamber of Commerce a business relationship with both universities. When an official is scratched, they trade with a member of another officiating crew. These scratches are important, especially with the legalization of sports gambling. The SEC isn’t the only entity that investigates each official. The bookies do too. “I heard in Vegas they know our names and our stats,” Crawford says.

The two-day camp for Carter’s crew is winding down. Officials are inside the Georgia coaches’ locker room preparing for the upcoming scrimmage. It will be their first outing together with their three new members. They’re hoping to iron out any kinks, which begins even before leaving the locker room. As they’re slipping on their uniforms, old members are telling new members how little they want the headsets used. Carter insists that his crew only speak on the headsets when absolutely necessary. That’s new for Flowers and for Middlebrooks, who come from more chatty groups. An hour later, on a scorching, sun-splashed day in Athens, this crew of officials works as one unit, one team, for the first time ever, marching up and down the field, where at one point a Georgia lineman approaches a couple of them with a request that’s so fitting. “I got a question,” he says, “about holding…”