'Out of the Dark Ages': How LSU's Lethal New Spread Attack Was Built

This story appears in the Sept. 23, 2019, issue of Sports Illustrated.For more great storytelling and in-depth analysis, subscribe to the magazine and get up to 94% off the cover price. Click here for more.

Buddy Breaux watched LSU play Texas from the far reaches of Darrell K Royal Stadium, the tip-top of the upper deck, in the “next county,” he says with a laugh. But no distance, big or small, could keep him from recognizing a truth about what he was seeing below: His LSU Tigers football team looked different.

There were rarely snaps under center. There were no fullbacks and sometimes there were even no running backs. There were—gulp—no huddles. There were as many as five receivers on the field. There were crossing routes and verticals. There were deep ins and deep outs. There was, unfathomably, the spread offense.

“All of my friends . . . we’re looking at each other pinching ourselves. ‘Is this real?’” says Breaux, 69, a past president of the Tiger Gridiron Club. “A lot of the general fan bases in college football, they have no idea of the frustration the fans had here.”

LSU’s 45–38 win over Texas on Sept. 7, in which the Tigers had 573 yards, 28 first downs and five touchdowns—stretches beyond its significance on the surface: a road victory over a top 10–ranked, Big 12 powerhouse. In front of millions on national television, in a sold-out stadium of mostly burnt orange, a program, stuck in the Stone Age offensively, signaled thunderously that it has sprung into the new millennium of offensive football.

“People are going ballistic,” says Dan Borne, the longtime public address announcer at Tiger Stadium. “It’s shock and awe when that offense gets the ball.”

Even the governor is on board. “The excitement is real, and it is palpable,” says John Bel Edwards.

To understand the significance of LSU’s recent offensive transformation, you must understand its checkered past. There were serious problems in the passing game, from scheme to personnel. LSU had six different starting quarterbacks in six seasons (2011–16), and up until last season it had not cracked the top 80 in passing since 2013, a season in which the Tigers had future NFL stars Odell Beckham Jr. and Jarvis Landry. Even then, they finished 45th nationally in passing.

Through three games this year, the Tigers are second in the nation in passing yards per game, at 436.3. According to STATS Perform, 128 of their 134 snaps in their first two games were out of the shotgun, a 95.5% clip. In 2017, 39.7% percent of LSU’s snaps were out of the shotgun, the 12th-lowest rate in the FBS and the second lowest in the SEC. During Les Miles’s last five years as coach, from 2012 to 2016, 33.2% of snaps came out of the shotgun.

The personnel use has dramatically changed, too. LSU is using more wide receivers and fewer tight ends. The Tigers operated from formations with three or more receivers on all but two plays through the first two weeks. In Miles’s last five years, just one-fifth of the Tigers’ snaps were from a formation with three or more receivers.

“I wish I could have had a chance to broadcast [the new] offense,” laughs Jim Hawthorne, who spent 36 years as LSU’s radio play-by-play voice and is now retired. “Fans I know have said, ‘Wow! That’s the real deal!’ And then they say, ‘What if we had been running this offense with those two receivers, Odell and Jarvis?’”

Jacob Hester, a fullback and tailback from 2004 to ’07, was a bruising benefactor of Miles’s run-first scheme. He defended Miles from critics, pointing out that between 2005, when Miles was hired, and ’15, LSU won 77.8% of its games, a pair of SEC championships and the ’07 national title.

But as offenses transformed to shotgun-based spread schemes, Baton Rouge remained an island employing fullbacks, tight ends and the I. For Hester, things changed in the 2016 season-opening loss to Wisconsin. With expectations of a tweaked offense, LSU executed on the first play of the season, a toss dive from the I-formation. Leonard Fournette was stopped for a three-yard gain, the No. 5 Tigers went three-and-out and lost 16–14 to the unranked Badgers.

“That was the breaking point to me and all the people that thought LSU could do it the old-fashioned way,” says Hester, now a radio show host in Baton Rouge. Miles was fired three weeks later, after an 18–13 loss at Auburn. Ed Orgeron was promoted from defensive line coach, and LSU had taken its first step toward offensive enlightenment.

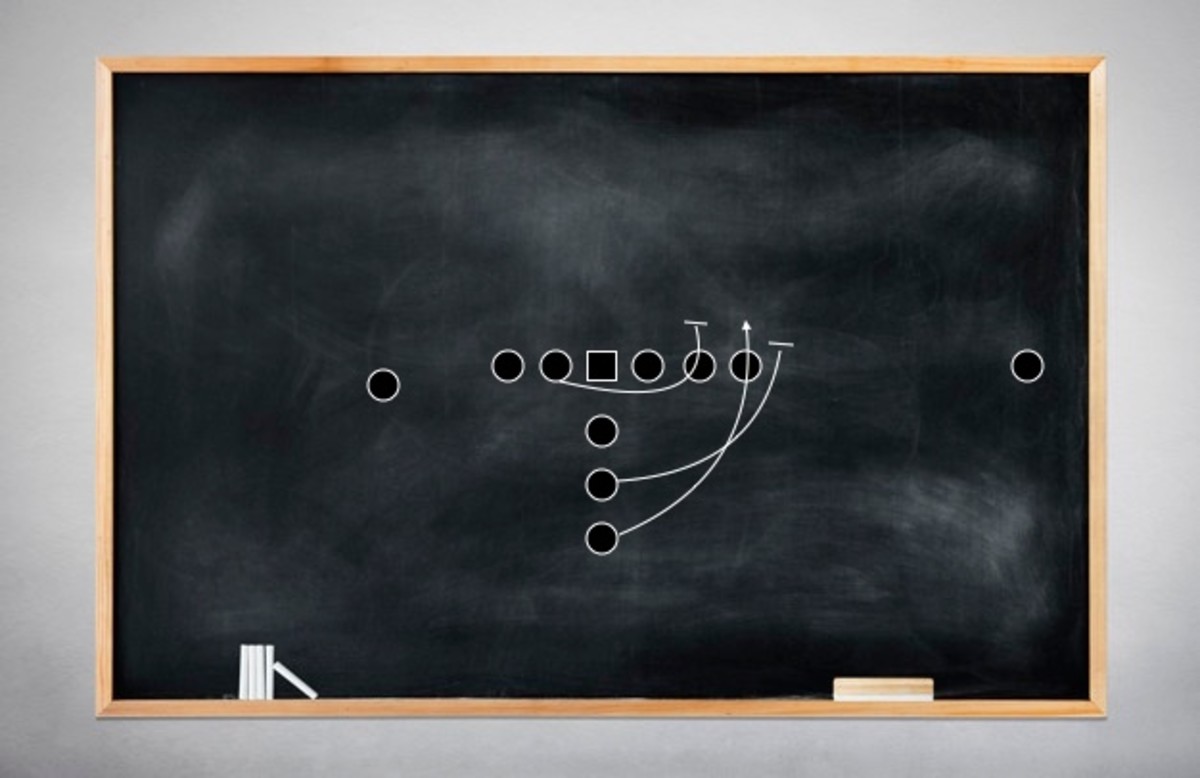

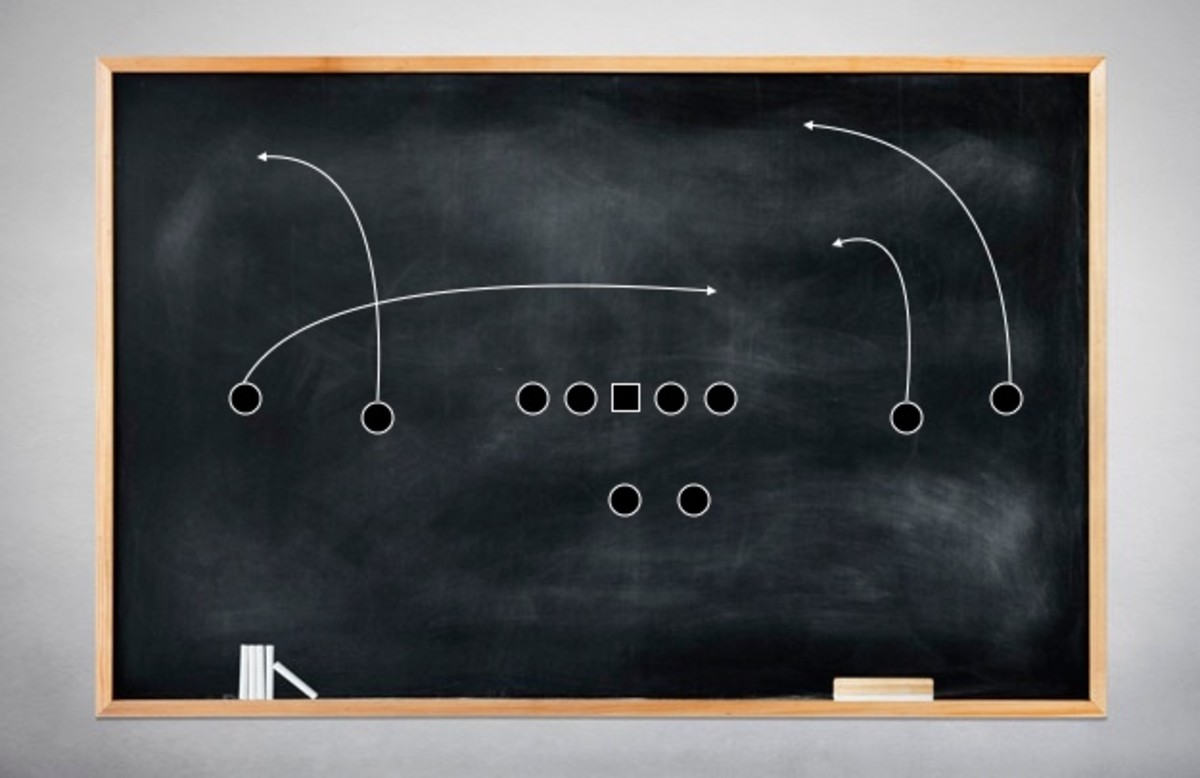

Side-by-side formations depict the difference between LSU's old (left) offense and its new (right) spread one.

How LSU got from a notoriously outdated ground-based offense to this juggernaut is a winding journey with two essential events: the acquisition of a transfer quarterback from Ohio State, Joe Burrow, and a gutsy decision by Orgeron to hire a 29-year-old, low-level NFL staffer to overhaul an offense that was consistently winning double-digit games every year.

That coach, Joe Brady, the team’s passing game coordinator and receivers coach, does not lack in confidence when asked about the risk it took to hire him. “If you ask me, I think it was a pretty damn good decision,” says Brady, who was hired away from the Saints last January. “It might be something that could rub people the wrong way, and they could sit there and say, ‘Why this or that?’ But Coach had a clear-cut vision of what he was looking for. We were looking for the exact same thing. Our visions matched.”

Of course, the change goes beyond visions and schemes. The Tigers have a strong, competent quarterback built for the spread. Burrow, a redshirt senior, was recruited and signed by Ohio State to operate in the system. When he decided to transfer in the spring of 2018, Burrow and his father, Jimmy, a longtime defensive coordinator at Ohio University, were aware of LSU’s offensive reputation. In fact, others used that to try to influence his decision.

“We were, by other coaches, reminded, ‘Hey, you’re going down there to be under center and hand the ball off to a tailback 60 times a game,’” Jimmy recalls. “We had to research the QB situation then and be convinced that things are going to be different with the offense.”

In January, as winter workouts began at LSU, offensive coordinator Steve Ensminger walked into the quarterback meeting room, distributed a new playbook and told his players, “We’re going to the spread, baby!”

The change was long overdue, and the Tigers weren’t the only college football blue blood to embrace the new system. USC and Michigan, who for years clung to a pro-style system that leaned on a bruising rushing attack, spent the offseason transitioning to the scheme that has been run by the last five national champions.

The spread converts even the most traditional coaches, including Nick Saban at Alabama. Starting with the hiring of Lane Kiffin in 2014, his program has slowly evolved into the shotgun-based RPO scheme we see today. “In defending some of this stuff through the years, you see the issues and problems that it creates,” Saban said, “and you try to implement some of these things yourself.”

Greg McElroy, who played quarterback for Saban from 2007 to ’10 and is now an ESPN analyst, believes the coach’s conversion was triggered by back-to-back losses to a spread-centric Ole Miss team in 2014–15. “If you can’t beat’ em,” McElroy says, “join’ em.”

So perhaps it’s no coincidence that LSU adopted a more wide-open offense after losing to Alabama eight straight times. Change isn’t always brought on by a lopsided series against a rival, though. Many coaches overhaul their offense out of desperation, a hopeful job-saving move. That’s the case for USC’s Clay Helton, whose prospects were not helped by Saturday’s 30–27 loss to BYU. But sometimes it works wonders. At Missouri, Gary Pinkel failed to reach a bowl in three of his first four seasons before a switch in 2005 to the spread extended his stay by a decade. At TCU, Gary Patterson’s 2013 team limped to a 4–8 record before a move to the spread the very next year resulted in a No. 3 ranking.

There are holdouts, though. Stanford, Wisconsin, Boston College, Michigan State, Kansas State and Iowa, among others, still operate from a traditional offense. “You can score a lot of points that way,” McElroy says. “I don’t think you can score a lot of points that way against Alabama and Clemson.”

Case in point: LSU scored 10 total points in its last three games against the Tide. The Tigers will find out just how improved they are on Nov. 9, when they travel to Tuscaloosa. “At LSU,” says Rick Neuheisel, the former coach who’s now an analyst for CBS, “everything is measured by beating Alabama.”

Bob Shoop flipped between watching three football games the night of Sept. 7: LSU–Texas, Penn State–Buffalo and BYU–Tennessee. One stood out from the others. “LSU has won games in the past like 14–13 or 17–10,” says Shoop, the defensive coordinator at Mississippi State. “They won this one 45–38. My response to that initially is, ‘Welcome to 2019.’”

Shoop and his boss, Bulldogs coach Joe Moorhead, played a roundabout role in that transformation. Brady, a Florida native who played receiver at William & Mary, worked under both of them as a graduate assistant at Penn State in 2016. At Penn State in 2015, one of the graduate assistants working under them was Brady. The hardworking youngster—when he spoke to SI last week at 11 p.m., it was the earliest he had left the LSU football facility since camp began—was soon hired by the Saints as an offensive assistant, the NFL’s equivalent of a graduate assistant.

During the 2018 offseason, Orgeron asked several New Orleans assistants to give presentations to the Tigers’ offensive staff. Brady did a segment on the RPO. A few months later Orgeron turned to his offensive coordinator with a plea. “We’ve got to go spread,” he told Ensminger. This was a vision Orgeron held since taking over for Miles. But having inherited a team built for the run, he knew it was going to take time. The roster had eight fullbacks. At one point in ’17, LSU had as few as eight healthy scholarship receivers. “It was painstaking,” Orgeron says. “I would look at the offense and say, ‘This is not what it is supposed to look like.’”

In addition to a QB and a deep group of receivers, he needed Brady. In 2017 he’d taken his first trip to Louisiana—on Valentine's Day, as luck would have it—to interview with the Saints, whose assistant offensive line coach, Brendan Nugent, had coached Brady at William & Mary. Days later Brady found himself in some awe-inspiring situations: seated next to Drew Brees or listening to Sean Payton construct plays. He spent long days and nights poring over game film. He would have done it for free. Two years later he’s gone from making five figures to pulling in $400,000 a year while scheming the offense of the fourth-ranked team in the country.

“Lucked out with all that,” Brady says. He’s humble. It is not his offense, he says, but is instead a conglomeration of ideas from the staff organized by Ensminger. He’s too modest to tell you that many of the ideas are his, the drop-back passing concepts from Payton and the RPO game from Moorhead. “The majority of stuff I brought is from New Orleans,” he says, but there are other schemes weaved in, including wrinkles from the Kansas City Chiefs. LSU players spent the offseason watching film of the Saints and Penn State.

Ensminger and Brady, separated by more than 30 years in age, work in tandem to create the game plan and call the plays. Ensminger decides when Brady gets the call. “Hey, you got it on this one!” the 61-year-old will say. “It’s all predicated on how he’s feeling and if he’s in a groove,” Brady says. Sometimes Brady gets a third-down play. Other times he calls an entire drive.

No matter who makes the call, it’s usually aggressive. Late in the Texas game, LSU was leading by six points at its own 39-yard line with less than three minutes left. Facing third-and-17, Orgeron asked Ensminger through the headsets, “What you think about a four-minute offense?”

“Nope. We’re going to pass the ball and go down there and score,” Ensminger told him.

Orgeron’s reply: “Go ahead.”

For Brady, it was an easy call. “It’s all I really know. I’ve been with Sean Payton for two years, there’s nothing that he’s scared of. We had a good bead on Texas. They’re a pressure football team. In a critical situation, they’re going to want to send the house and knock you back even more, force you into a turnover.”

Ensminger called four vertical routes and kept the running back, Clyde Edwards-Helaire, in the backfield as a sixth pass protector. In a collapsing pocket, Edwards-Helaire made the saving block to provide Burrow with enough time to find receiver Justin Jefferson, who broke a tackle and jaunted 61 yards for the game-securing touchdown. “Last year,” Burrow said, “we’d have pounded the run game.”

When he arrived in Baton Rouge in January, Brady knew of LSU’s offensive perception—run the football and play good defense, he says—but he never really looked at it from a “Hey, LSU has never done this type thing.” He realized quickly when his phone after the Texas game was bombarded with texts. “How does it feel!?!” many of them said. His response: I don’t know. “I just have no idea. We’re in season. We play all these dang night games. You have success in a night game, you wake up and go back into work. It’s a new week.”

On Oct. 19, LSU plays at Mississippi State in an SEC West battle. Brady and Ensminger’s offense meets Moorhead and Shoop’s defense. “Hopefully,” says Shoop, “our fans will ring those bells loud enough to confuse Joe Brady."

Nearly 40 years ago, Arkansas coach Lou Holtz switched away from the veer option solely because of the disadvantages it created in recruiting. Holtz says he had trouble signing skill players. Today those teams that moved from the option to a more pro-style offense are now switching to the spread for the same reason. "If you're a receiver, would you rather sign with this offense or LSU's old offense?" asks Pete Jenkins, who retired as LSU's defensive line coach in 2017.

Ironically, the Tigers have never had trouble signing good players. In fact, Louisiana is talent-rich, and six of LSU's last seven signing classes have ranked in the top seven nationally. However, most high school athletes these days are playing in a version of the spread. It explains why more true freshman quarterbacks than ever are playing and succeeding: They've spent years operating in the same schemes at the prep level. Now that LSU is running an offense its recruits are familiar with, they have an easier adjustment to the college game.

But the switch to this style of offense isn't all positive. There are drawbacks to a quick-paced system that puts the ball in the air so much. One of them reared its head in Austin: The Tigers lost the time of possession battle by eight minutes. Their defense was on the field for 85 plays, the most in a regulation game since 2013. As a result, LSU's defense, one loaded with five-star athletes and led by the highest-paid defensive coordinator in the nation, Dave Aranda, allowed 38 points and 530 yards. Even against Northwestern State last Saturday—a game LSU won 65–14 and completed 29 of 33 passes for 488 yards—the D was on the field for more than 33 minutes. "You get the people and they want to go so fast and run so many plays as quickly as they can," says Randy Edsall, the UConn coach. "That's all well and good, but if you're not making first downs or scoring points, you're putting your defense in a heck of a bind."

Neuheisel expects a "correction" from the traditional powers that have recently switched, meaning the LSUs and Alabamas will drift back toward their old ways. "They'll go too far, and they'll realize maybe Burrow gets nicked or they can't salt the game away," he says. "We saw Alabama not be able to run the ball in the national championship game [loss to Clemson last year]."

Edsall agrees. "Like anything else, things evolve," he says. "You'll start seeing more people doing things under the center."

There are other issues. Defensive coaches now have three full games of LSU's new offense. That's two more than Texas coaches got. "This is the SEC West," says Shoop. "People adjust."

But LSU's offense is finally, in the words of Buddy Breaux, "out of the dark ages." And Brady isn't planning on making it easy for foes to catch up. "We're just three games in," he says. "There's so many levels we have to reach. We've barely scratched the surface."