At LSU, Football and Politics Converge in a Way That's Uniquely Louisiana

BATON ROUGE, La. — John Bel Edwards does not claim to be a prognosticator of every college football game, just those involving his favorite team. When it comes to LSU, the Louisiana governor has impeccable knowledge because he’s got an inside source, a man who knows more about the Fightin’ Tigers than anyone else, a close confidant he communicates with on a weekly basis: the head football coach. If you don’t believe him, because after all he is a politician, Edwards will show you proof. He will reach into the pocket of his jeans, remove his iPhone and find the latest text message sent to him by Ed Orgeron—like the one he received Thursday morning, two days before LSU’s top-10 clash at Tiger Stadium against the Florida Gators.

We’ll be ready to win. Have a great day Saturday. Geaux Tigers! See you soon!

The governor glances up from his phone after reading Orgeron’s message. He’s riding in the middle seat of a black Chevy suburban, surrounded inside by various staff members and security officials, on a political parade around south Louisiana, some last-minute campaigning for his re-election bid. This is Saturday at 3 p.m., four hours before the Tigers kick off against the Gators and five hours before election polls close. “Now, if this doesn’t happen, don’t quote me on it,” he says, “but normally I can tell by the text message I get from the coach whether they’re going to win. I’m serious. If he doesn’t feel really good about their preparation and stuff, I kind of get a sense of it. He tells me that they are ready to play tonight and that we are going to win. When he tells me that, we always win.”

For outsiders, this seems bizarre—the coach of the state’s flagship football program texting with the state’s governor. For those here in Louisiana, this is normal, the latest example of a near century-old relationship between LSU football and Louisiana politics. This bond is steeped in history, rooted in passion and adorned with truly unbelievable tales—one former governor insisted on calling plays during games and another skipped his own election party to watch the Tigers.

Every decade or so, these two giants, LSU football and Louisiana politics, collide on one epic Saturday in the fall. That happened here this past weekend. No. 5 LSU hosted No. 7 Florida while all around the football hoopla a gubernatorial election unfolded (yes, Louisiana has Saturday elections). It was a confluence of Louisiana’s most kingly marriage, Orgeron and Edwards, the anointed leader of each, rooting for the other, both engrossed in an epic fight in the same town at the same time, their careers and futures potentially hanging on the results.

“It’s the convergence of everything in Louisiana in one day,” says Mitch Rabalais, a former political reporter now working in the LSU president’s office. “It’s a perfect storm.”

Imagine it for just a second: the LSU football coach on an airboat speeding in the dark of night toward a floating house, where inside waiting for him is the governor of Louisiana. Well, that’s exactly how it happened. Edwards and Orgeron met for the first time in January 2017 at a duck camp accessible only by boat and located in Orgeron’s home parish of Lafourche. “We hit it off from there,” Edwards says.

The relationship blossomed. Edwards, a former high school quarterback from the tiny Louisiana town of Amite, has attended LSU practices, even throwing passes to Tigers receivers at one. Orgeron is an occasional visitor of functions at the governor’s mansion. They’ve appeared in commercials together, and their wives, Kelly Orgeron and Donna Edwards, began playing tennis together. Two years ago, not long after their first meeting, Edwards invited Orgeron to attend a satirical play produced by the Louisiana Capitol press corps. Their relationship was the focus of one particular skit, dubbed to “Friend Like Me,” one of the musical elements from Disney’s Aladdin. “When the governor invites you somewhere,” Orgeron playfully whispered during an interview at the function, “you go.” In June, LSU freshmen and staff were treated to a dinner at the mansion, and at least once over the last two seasons, Edwards has traveled with the team for a road game.

“In Louisiana, politics and football are our two favorite contact sports,” laughs Marty Chabert, a close ally to Edwards and a former member of the Louisiana Senate. “Politics and LSU football have long, long been joined at the hip.”

In an election year, the relationship between the governor and Orgeron has drawn the ire of Edwards’s political opponents. Edwards is a Democrat who won a landmark election four years ago in a mostly red state. During an event in April, Orgeron introduced the governor in a way that some viewed as an endorsement. U.S. Senator John Kennedy, a Republican, said he was “appalled” after watching video from the event, denouncing such a move from a celebrity figure employed at a public university. The story grabbed enough attention that the school released a statement defending Orgeron for exercising his constitutional right. Edwards calls the entire situation “silly,” chalking it up to political maneuvering from his adversaries.

College coaches wandering into politics is not completely unheard of. Alabama coach Nick Saban was featured in a campaign ad last year for a long-time friend in West Virginia. At LSU in 2015, then-coach Les Miles attended an event in honor of then-Gov. Bobby Jindal’s presidential campaign. For the politician, it is a smart move, says Tucker Martin, a former Virginia-based Republican operative and a rabid college football fan. “If you have a figure who transcends politics, those are the ones who can move the needle,” he says. “Go to any game, look down your row and you’ll see Democrats and Republicans. The one man who can speak for all of them? The coach they root for.”

There is politics at play here on both sides. The governor hand picks members of a powerful decision-making board at LSU that ultimately hires—and fires—the university’s top leaders, including the president, the athletic director and, of course, the football coach. Board members terms are staggered. If he wins re-election, Edwards will at some point in his second term have selected a majority of the board. “That’s the big question,” says Robert Mann, a political historian and communications professor at LSU since 2006. “Let’s hope it never happens, but it would be interesting to see if LSU fell on hard times, if people would start pressuring Edwards to do something about it or if Edwards would feel responsible.”

Those close to the two men say their friendship is genuine. They are “kindred souls,” says Jim Engster, a media titan in Baton Rouge who’s covered Louisiana politics since 1979 and hosts a monthly radio show with the governor. Orgeron and Edwards are two Louisiana-born men separated in age by just five years, a couple of underdogs who somewhat late in life reached the pinnacles of their fields within the boundaries of their own home state. They both grew up listening to LSU games on the radio, and Edwards, a graduate of Army, received his law degree from LSU in 1999.

Genuine or not, it is a politically-fueled symbiotic relationship. “The governor can make or break a football coach,” Engster says. “And a football coach, if he’s winning, adds to the cache of the governor.” And if he’s not winning? “You run for whatever hills we have in Louisiana.”

Back in that Chevy suburban, the governor is bounding down broken Baton Rouge streets en route from one campaign stop to another. Outside, vehicles honk at him, some of them sporting purple-and-gold flags attached to their windows. Within two hours, the LSU football team will march down Victory Hill for their traditional pregame walk to Tiger Stadium. The governor won’t be there, a rare missed home game, but that doesn’t mean he’s completely removed himself from college football. Between campaign stops, he checks scores from the ESPN app on his iPhone. No. 3 Georgia has lost at home to unranked South Carolina. “I’m not one of these people that obsess over rankings, especially early in the season,” he says with a dramatic pause, “but I know that they were ahead of LSU in the rankings.”

*****

Right around the time the leader of LSU’s football program appeared on ESPN College GameDay, his political counterpart was speeding from New Orleans’s Lower Ninth Ward to Canal Street. It was about 9:30 a.m. Saturday and Edwards, already in the city for election morning events, had received disturbing news from a communications staff member. The Hard Rock Hotel, in the heart of New Orleans’s business and tourism district, had partially collapsed, sending large chunks of debris crashing onto Canal Street, the city’s main north-to-south thoroughfare.

More than a dozen people were hospitalized and two were eventually confirmed dead. Edwards visited the site to speak with officials. Campaigning, though, never stops. Within a few hours, he was standing on Airline Drive in Baton Rouge alongside supporters waving signs as traffic whistled by, an election day tradition. He looked like any other Louisianan, dressed in jeans, a light blue fishing shirt and boots made out of Ostrich (yes, the bird). Jayce Genco, a 25-year-old LSU alum and the governor’s traveling communications staff member, makes it abundantly clear what today is about—yes, there is a big football game, but this is election day. “The football game,” he says, “is a little bit of lagniappe,” an old Creole term meaning a bonus or small gift.

Louisiana is unique in that it not only holds statewide elections on Saturday but it also uses what’s called an open primary, where all candidates are on one single ballot. Any candidate who receives more than 50% of the vote is declared the winner. If no one reaches that mark, the top two vote-getters enter a runoff a month later. As the incumbent, Edwards is the only serious Democratic candidate, but he’s got two significant Republican challengers, businessman Eddie Rispone and U.S. Representative Ralph Abraham. Because of the football game coinciding with the election, a record number participated in early voting. “There were a lot of people who wanted to tailgate,” Mann says.

By 7 p.m., his campaign events behind him, the governor returned home to watch the first half of the LSU game from the mansion’s dining room, his family surrounding him, his eyes fixated on the flatscreen television before him. He celebrated touchdowns and, like the rest of us, he bemoaned poor officiating. When Justin Jefferson caught a 7-yard touchdown pass from quarterback Joe Burrow, the Tigers took a 14–7 lead. In the political world, almost at that very moment, the polls closed. Edwards’s phone, hours earlier used to update football scores, now served as a tracking device for election results. Within an hour, the obvious was apparent: He would need to win a runoff on Nov. 16 against Rispone. The governor finished with just shy of 47% of the vote.

Edwards would eventually head to the site of his post-election party, the Renaissance Hotel in south Baton Rouge. In a massive ballroom, a giant projection screen flanked each side of the main stage. One showed election results, the other the LSU football game. In what was surely not a coincidence, the governor took the stage six minutes after the Tigers clinched their 42–28 win over the Gators to remain undefeated.

“We’ve got a little more work to do,” Edwards told the crowd. Already, that work is starting. If you need any more link between LSU football and Louisiana politics, look to the Democratic Governor’s Association’s latest attack on Rispone. The DGA launched a website this week playing up football in an assault on the businessman’s platform. The site’s main graphic art pictures two cartoon football players, one featuring Edwards’s face and another Rispone’s. The only different between the two players is the color of their uniforms. Edwards is in purple and gold. And Rispone? Crimson and White.

*****

On Saturday night, the athletic director suite at Tiger Stadium provided the best example of the LSU football program’s affair with politics. James Carville, a Louisianan, LSU graduate and outspoken Democratic political commentator, watched the game from the suite of athletic director Scott Woodward, who just so happens to be a former political lobbyist in the state. He is long past the political time in his life. “I wasn’t worried about election results,” he says of Saturday. “I was worried about a 42-28 football game and making sure everything went correctly.”

Experts say the link between LSU football and politics began with Huey Long, governor of the state from 1928–32 and then a U.S. Senator before his assassination in 1935. He’s known here as the grandfather of LSU football, the man who used his powerful influence to bolster the program. Political experts describe Long as a quasi-dictator. “What he wanted,” Engster says, “he was going to get.” He wanted a world-class football program at the university residing three miles south of the Louisiana Capitol.

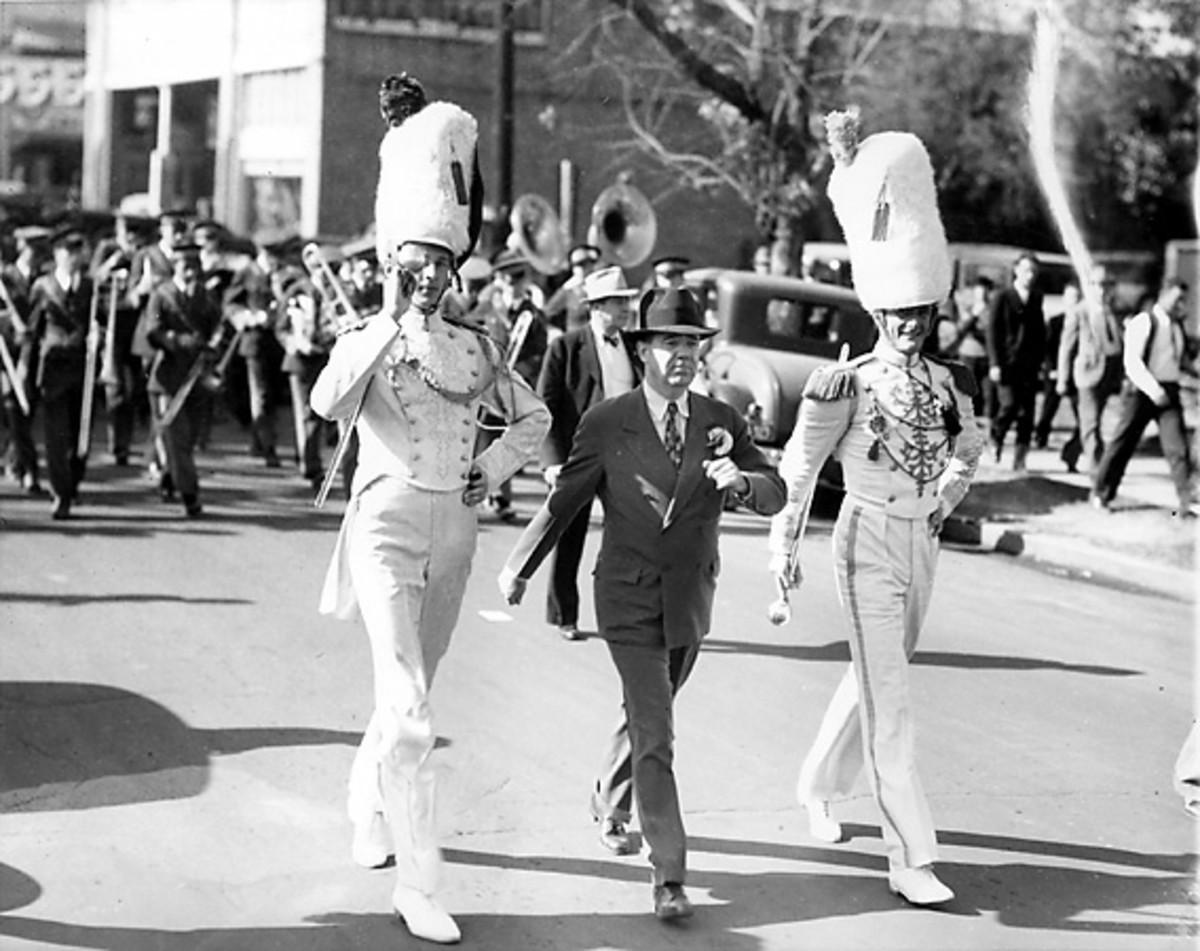

Long expanded the Tigers marching band, and he convinced state legislators to fund the expansion of Tiger Stadium by building dormitories into the bleachers. He was hands on. Long hosted football recruits in the governor’s mansion, delivered speeches to players and often marched with the LSU band down Baton Rouge streets. He was a fixture on the LSU sidelines and sometimes got involved in mid-game disputes with coaches over play-calling. One coach, Biff Jones, quit in 1934 over an argument with the politician. Over what, you might ask? Long wanted to give the halftime address to the team.

More than 85 years later, Edwards got to address the LSU football team—in spring practice. The governor is not affiliated with the daily affairs of the program, aside from his weekly text exchange with the coach. He watches most home games from his suite in Tiger Stadium, not on the sideline. Despite his modest involvement, Edwards’s relationship with Orgeron and the program is another vestige of Long, a tradition that various Louisiana governors have embraced through the years, most notably John McKeithen, governing the state from 1964–72. McKeithen, an attendee at many LSU practices, was maybe the most diehard LSU fan of all the Louisiana governors. He once skipped an election party to travel to Mississippi for the Tigers’ game against Ole Miss, and after one loss, he notoriously used his fist to shatter his limousine window, says Engster.

“We’re in a state where football means more here than it does in other parts of the country, and we’ve got only one major university,” Engster explains. “LSU football is paramount to any governor. No governor is going to say they don’t care about it—that would be political suicide. They preside over the action on Saturday night as if they’re some regal emperor ruling from the stands.”

For some, LSU football is seen as a beacon in a state that normally ranks toward the bottom nationally in education, health and economic indicators. Speaking from the press box as Tiger Stadium’s crowd rumbles below, Carville describes the program as “the whole ball of wax. There isn’t another major university here. Most of the political leaders in the state came out of LSU.” Mann sees LSU football as a “cultural touchstone” that every state leader grasps for popularity’s sake. He equates the sport to another passion in this state: food. “You either can peel crawfish or you can’t,” he says. “It’s a signal: I’m one of you.”

*****

Roughly 40 hours removed from his team’s two-touchdown victory and Edwards’s disappointing primary news, Orgeron walks through a rain shower Monday speaking about his relationship with the political leader of the state. The coach received a congratulatory text from Edwards after the win over Florida, and Orgeron replied by wishing good luck to him in the runoff.

Given election results, some might say that Orgeron is more popular these days than his political equivalent. After all, the LSU football team is 6–0 and ranked No. 2 in the nation. The Tigers have the Heisman Trophy favorite at quarterback, Burrow, and an offense that’s scoring more points than any other team in football. For the third time in nine years, they are on a collision course toward an unbeaten bout with top-ranked Alabama, the championship standard in the game and a thorn in this program’s side. LSU has not beaten Alabama since 2011, the last year the teams met as No. 1-vs-No. 2. “A championship-winning LSU football coach is the most powerful person in Louisiana, more powerful than the governor,” Engster says. “If he beats Alabama, he’ll be God. And this year, he may.”

The Crimson Tide are on many minds here in Baton Rouge, a truth that has lingered for nearly a decade. Even the politicians are craving a victory over the vaunted Tide. It took just three months for them to make that point to their new head coach. At a function in Orgeron’s hometown celebrating his hire two years ago, former Louisiana governor Edwin Edwards, then 89, took the stage, rallied the crowd and ended his sermon by gesturing to Orgeron, “I’m looking forward to the day we beat Alabama!”

Edwards is no friend of the Tide. In fact, back in his Chevy suburban, he is scrolling through scores on his ESPN app when he stumbles upon one in particular that triggers him to announce it to a car full of people. “A&M is up on Alabama,” the governor excitedly says, before gloomily completing his full thought, “halfway through the first quarter.” Moments later, Edwards and his convoy arrive at his final campaign stop in Baton Rouge, around 4 p.m. Saturday. Police detail unload out of two other black suburbans, piling out into a parking lot of a Family Dollar, where the governor will spend about 20 minutes on a street corner waving signs that read, “Geaux Vote!”

According to public voter registration data, Orgeron registered to vote this year for the first time as an Independent. He confirms that during an interview Monday. He politely declines to reveal the candidate for whom he voted, but he did call Edwards “excellent” for Louisiana. Edwards, meanwhile, has a real fight on his hands. If he is successful, it would be a historic victory. No incumbent governor in Louisiana has ever won when forced into a runoff.

A political influencer at Edwards’ post-election party in Baton Rouge wonders aloud if Orgeron will endorse the governor in a more public way than he did this spring, perhaps with a campaign ad. Or maybe he’ll stay out of it all together. After all, Edwards’ runoff competitor, Rispone, is a longtime Baton Rouge businessman who has a degree from LSU. One of Rispone’s campaign ads features the 70-year old in a setting made to replicate an LSU football tailgate, replete with purple-and-gold table clothes and a crawfish boiling pot with Rispone in the foreground holding a football. “Here in Louisiana, we play to win in every single game,” Rispone says in the commercial. “It’s time to lead the South in football and in jobs.”

Welcome to Louisiana, where football and politics are like sticky rice and steaming gumbo. They just go together.