Alabama DC Pete Golding's Louisiana Roots Have His Hometown Torn vs. LSU

HAMMOND, La. — Scott Eyster is a torn man ahead of Saturday’s 1-verse-2 bout between LSU and Alabama. On one hand, his longtime best friend is Alabama’s defensive coordinator, Pete Golding. On the other hand, his longtime allegiance is to LSU, his home-state school. He’s attending the game, will sit in the Bama section and plans to even wear an Alabama shirt. However, his purple-and-gold loyalty has its threshold. The color of that Alabama shirt is gray. “Pete knows I won’t wear Crimson,” Eyster smiles. “It’s hard to wear that Crimson.”

You probably know Golding as the Tide’s 35-year-old defensive coordinator, a carbon copy some say of coach Nick Saban, a wunderkind who landed his first DC job at 23. Here, they know him as a south Louisiana boy, raised 50 miles from Baton Rouge by a mother who holds an LSU degree and is surrounded by purple-clad friends. Welcome to Golding’s hometown: Hammond America, a nickname that speaks to this place’s personality. Hammond is the perfect representative of any American small town. It features an old downtown built along a railroad track, is at a literal crossroads of two bisecting major thoroughfares, I-55 and I-10, and is wedged between two major cities, Baton Rouge and New Orleans. It is a quiet enclave from the big city lights, an escape from the merciless traffic of Louisiana’s two largest metro areas.

Hammond does football like you’d think: big. They root for the hometown Southeastern Louisiana Lions of the FCS, pull for the NFL’s New Orleans Saints and stump for that SEC West program just up the road—not the one two states over. “Everybody loves Pete and all, but people around here, they don’t give a s--- about Alabama,” says Warren Eyster, Scott’s father, who coached Golding at Hammond High. “Here, it’s all LSU.” Golding’s job has complicated matters in this town of 20,000. Their hometown hero is not only wearing enemy colors but on Saturday he’s responsible for trying to ruin LSU’s magical season and the Heisman Trophy hopes of its starting quarterback.

This matchup is dripping with drama. Two of the nation’s best quarterbacks lead two of the country’s most prolific offenses into a battle pitting the top two teams in college football. Lost in the buzz is a pair of highly paid defensive coordinators whose units, at times underwhelming, still rank among the sport’s best. How will they stop the other’s offense? They won’t, says Ron Roberts. “You’ve got to slow them down—can’t stop them.” Roberts would know. For a short stretch in the spring of 2007, LSU defensive coordinator Dave Aranda and Golding both worked under Roberts at Delta State. In fact, when Roberts watches each of their defensive units, he sees similarities. An odd-numbered front line, a fifth defensive back, two high safeties, a pattern-matching zone, simulated pressures. But don’t get too caught up in the football lingo. What’s important is that these two men operate similar schemes in which their offenses see every day in practice. Gulp. “They’ll have to have a heck of a plan,” Roberts says.

In Golding’s case, this is about more than Xs and Os. Would you want to be the first Alabama defensive coordinator in eight years to have LSU win a game against you? Now add in the fact that you’re from Louisiana and are scheming against an offense that has scored a total of 10 points in three years against your team. For Golding, this is as high pressure of a game as it gets. That’s why Tena Golding knows to not expect a call from her son this week. Tena is from north Mississippi and attended Delta State, where she met Pete’s father. Since the family’s move to Hammond in 1982, Tena has slowly climbed the ladder from math professor to administrator at Southeastern Louisiana. She’s now No. 2 in command at the 94-year-old, 14,000-student college nestled in the north part of town. She is a career-driven, systematic, shrewd person who arrives at a nearby Starbuck’s for an interview exactly one minute ahead of the agreed-upon time. The meeting must be conducted off campus and away from her office, she insisted, because she believes work and personal time should be kept separate. At one point during the interview, Tena wonders aloud if she should even be speaking to a reporter at all. Sound familiar? Pete isn’t so different from his mother and his mother isn’t so different from Pete’s boss, Saban, maybe the most regimented and methodical coach in college sports.

Like Saban, Pete was an undersized defensive back who played at a small college. He’s a grinder, too. “He doesn’t understand people who don’t give everything they have,” says Tena. Like everyone who works for Saban, Pete has long hours, usually 6:30 a.m. to 10:30 p.m. Tena waits by the phone most nights until about 11:15 p.m. About once a week, Pete calls her on his way home. If he doesn’t call by 11:15, she normally slips into bed, knowing that he’s either still working or with his family. Pete is a married father of three, all under the age of 8. His workaholic ways once prompted Tena to joke with her son that he should send her an emoji from time to time just to confirm his existence. “So now I’ll randomly get a single emoji from him,” she laughs. Being a coordinator for Saban at 35 cannot be easy, but Pete isn’t much for complaining. While other assistants hate the grind and are intimidated by Saban’s aggressive personality—you know, those sideline “ass-chewings,” as former Saban coordinator Lane Kiffin says—Pete embraces both. “This is Pete,” Tena says. “This is his calling. He talks about learning something new every day.”

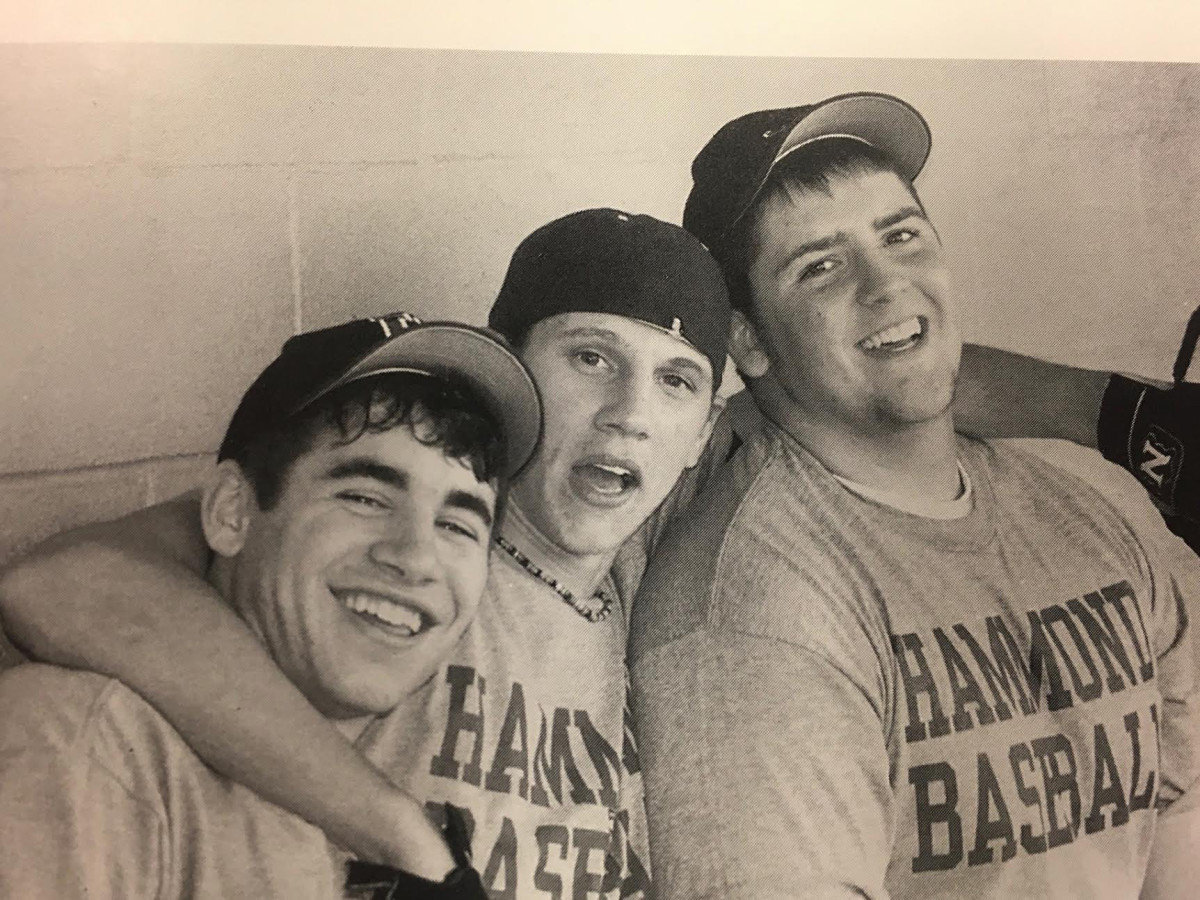

Pete isn’t a complete stranger to his hometown. His recruiting territory includes this portion of Louisiana and parts of Mississippi. Tena will sometimes receive a text from her son, “What’s for supper?” as he rolls into town unannounced. Eyster and Ryan Barker receive similar random messages from Pete. Eyster and Barker are Hammond natives who attended school with Pete from pre-kindergarten through college. They each played football for Hammond High and then Delta State, a unique trio of guys who stayed together for 15 years of their adolescence. Pete might text Barker and Eyster when he’s passing through on recruiting trips, and they’ll immediately round up friends for a night that may or may not include a beer or two. After all, this is south Louisiana. Barker and Eyster speak to a reporter from a Hammond barbecue joint called Salty Joe’s, where there is plenty of craft beer and frozen daiquiris, a Louisiana staple. “Do you want something local?” Barker asks as he nestles into his chair. “Do you like IPAs?”

Pete and his two buddies are celebrities in a town where booze and ball go together like a rolling pot of seasoned water and a sack of squirming crawfish. In fact, during an interview at Salty Joe’s, a neighbor walks through the door, gives finger guns to the bartender and plops down across from Barker. Within a minute, a server delivers the man a drink he never verbally ordered: vodka and water over ice in a tall glass. Everyone knows these guys here. They are small town football heroes. No Hammond High football team has ever won a 5A playoff game before or after the trio helped the Tornadoes do it in 2001, their senior year. In one high school yearbook, the three players are on the field at the same time—Barker at center, Eyster at quarterback and Pete behind them at tailback, his secondary position when not playing safety. More than anything, he shined as a returner and defensive back. “He was a ball hawk,” says Rob DeArmond, a Hammond High alum and sports journalist in the area for the last 20 years. “He always seemed to be at the right place at the right time.” There was one problem: Pete stood, at best, 5 feet 9 inches. “He was overlooked,” Tena says.

Pete, Barker and Eyster could have walked on at LSU to play for Saban, then in his third year with the Tigers, but they chose the less burdensome route for their families. None of them came from wealthy homes. “We wanted to help our folks by getting on scholarship,” says Barker, now executive director at a Hammond recreation park. Barker and Eyster, already committed to DSU, convinced Golding to visit during the spring of his senior season. DSU coaches surprisingly put him through an obstacle course of drills. He did well enough that head coach Rick Rhoades told Golding, “I don’t know how much scholarship money we have left, but you can have it all.”

Golding lettered in football, basketball, golf and soccer while at Hammond High, and he was good enough on the diamond that MLB scouts at least gave him a look. His academics were as good as his athletics. He was a member of the Beta Club, National Honor Society, FCA and made the honor roll every year of high school. He was class favorite as a senior and voted most athletic. He was, without a doubt, his mother and father’s son. They are both educators. Skip Golding is a high school coach now based in north Mississippi. Shelly Gaydos, now the Hammond High principal, taught Pete in an algebra honors class during his junior year. “I cheer for him to be successful,” Gaydos says, “but he makes it hard.” Gaydos is an LSU fan. In fact, so is her entire family. Her brother marched in LSU’s band, and her son once ripped up a recruitment letter from Alabama meant for his older sister before she even saw it. She wouldn’t have gone to Bama anyhow, shrugs Gaydos. “You can’t go where the red is,” she says. Like Eyster and many others in this town, Gaydos is torn about Saturday. She tries to justify her feelings from her office at Hammond High. Maybe LSU will win and Alabama’s defense will play well, she thinks aloud. Yeah, maybe.

Gaydos still refers to Golding by his real first name, Stephen. Many at Hammond High do the same. He’s even listed in yearbooks as “Stephen Golding.” He didn’t begin using the nickname Pete until his college days. His mother gave him the name Pete and, no, she will not share its roots. “It’ll embarrass him,” Tena says. His buddies do the sharing: it involves a cartoon he used to watch as a child. For those in Pete’s “inner circle,” Tena says, no one is surprised at his meteoric rise. And, boy, has it been meteoric. Pete is making $1.1 million this year as Alabama’s sole defensive coordinator after making $650,000 last year as its co-defensive coordinator. Two years ago, he made $200,000 as coordinator at UTSA and four years ago, he made $100,000 as an assistant at Southern Miss. Before that, he was a coordinator back home in Hammond at Southeastern Louisiana, and let’s just say the pay was in the five figures. He worked then under Roberts, just as much of a coaching mentor to Golding than anyone. He played for Roberts as a senior at Delta State, served as his graduate assistant in 2006 and coordinated his defense at DSU in 2011–12 before moving with him to Hammond.

The two still stay in touch regularly. Roberts recalls Golding’s senior season at Delta State when he returned a punt for a touchdown and was flagged for unsportsmanlike conduct for leaping into the end zone. Imagine him doing that as a player for his current boss? Roberts laughs. A year later, he remembers having to convince Golding to accept a full-time job elsewhere. In spring 2007, Golding wanted to remain on Delta State’s staff as a graduate assistant to work under Roberts and then-first year coordinator Aranda. Tusculum College, a Division II school in east Tennessee, had offered him a full-time assistant gig. “I had to almost make him go,” Roberts says. Roberts’s maniacal defense, one that he originated from old NFL DCs Don Capers and Dick LeBeau, rubbed off on Golding. It materialized during his second year as defensive coordinator at UTSA in 2017. The Roadrunners finished that season fifth in scoring defense. Eyster recalls that season. “People started looking… ‘UTSA? What the hell’s going on there?!’” Pete Golding was going on.

Two years later, Eyster is at Salty Joe’s talking about his clothing options as an LSU fan attending a game in Tuscaloosa where his best friend is the Tide’s defensive coordinator. Eyster plans to crash at the Golding house in Tuscaloosa this weekend. He has slowly come around to owning Bama gear. In fact, he has a pair of Alabama tennis shoes he sometimes wears to Tide games. He’d not dare wear them out here, he says, for fear of damaging his reputation and health. “If they’re not playing LSU, I want Alabama to win every game by 60,” he whispers. But what if they are playing LSU? “When they play LSU,” he pauses, maybe for effect, “I want Alabama to … do well on defense.”