The End of an Era: Inside Bud Foster's Decision to Retire

BLACKSBURG, Va. — Jessie Foster does not speed. She’s a wholesome civil servant, notorious for strictly abiding by all traffic laws. After all, how would it look for a Radford, Va., city council member to get ticketed in her own town. If the speed limit is 40, she is driving 39. Everyone in Jessie’s life knows this about Jessie, including her then-boyfriend Bud. So when Bud told her to break the law last November during an unscripted trip to the hospital, Jessie knew things were bad. “I looked over and I could see he was frightened,” Jessie recalls. “I did speed. I absolutely sped.”

Mere hours after Virginia Tech’s third consecutive loss, 52-22 at Pitt last year, doctors recorded Bud Foster’s resting heart rate at more than 200 beats per minute, roughly three times the average of a man his age. Worse news came later. No matter how much medicine physicians administered, Bud’s heart kept on pumping at dangerous levels, throbbing so hard he couldn’t stand, pulsing so much that the room was spinning. Finally, a decision was made, and out came what Bud calls the “shock cart.” Defibrillators are often associated with life-saving measures to revive heart-attack victims, but they can also help those in Bud’s position by resetting the heart rhythm back to normal.

Bud saw the cart wheeled into the room, and his eyes widened. This is a man whose square jaw and gruff glare is notorious throughout college football, a guy designated as the most blue collar among a profession of grinding dynamos, fearless and gutsy like the defensive units he coordinates. Here he was on a hospital bed, stripped of all invincibility, his heart now determining his fate as it jabbered against his sternum, and his eyes darting toward the defibrillator. “Let me ask you this,” he told doctors from that bed gesturing at the machine, “are you guys going to put me out when you do this or are you going to do this when I’m awake? Because I don’t want to see myself jerk.”

As the word jerk leapt from Bud’s mouth, he physically enacted the word itself, lurching his body upward in a motion similar to a defibrillator’s wanted effect. What happened next stunned everyone in the room: Bud saved himself.

*****

These are good times at Virginia Tech. The Hokies have crawled out of a 2-2 hole by winning six of their last seven games, are now ranked No. 23 in the nation and will play Friday for the ACC Coastal division championship at rival Virginia, to the victor go undefeated and defending national champion Clemson. Among the highlights in a Hokies turnaround that few saw coming is a defensive unit that has pitched consecutive shutouts against Power 5 competition, a rare feat that’s only been accomplished in college football seven other times since 2000, according to STATS Perform.

On Friday, the man behind that defense will coach his 290th game as Virginia Tech’s defensive coordinator and his 393rd game as an assistant here, the longest tenured assistant coach at one school in Football Bowl Subdivision. It will be his last regular season game in such a role, having announced in August his retirement from the sport.

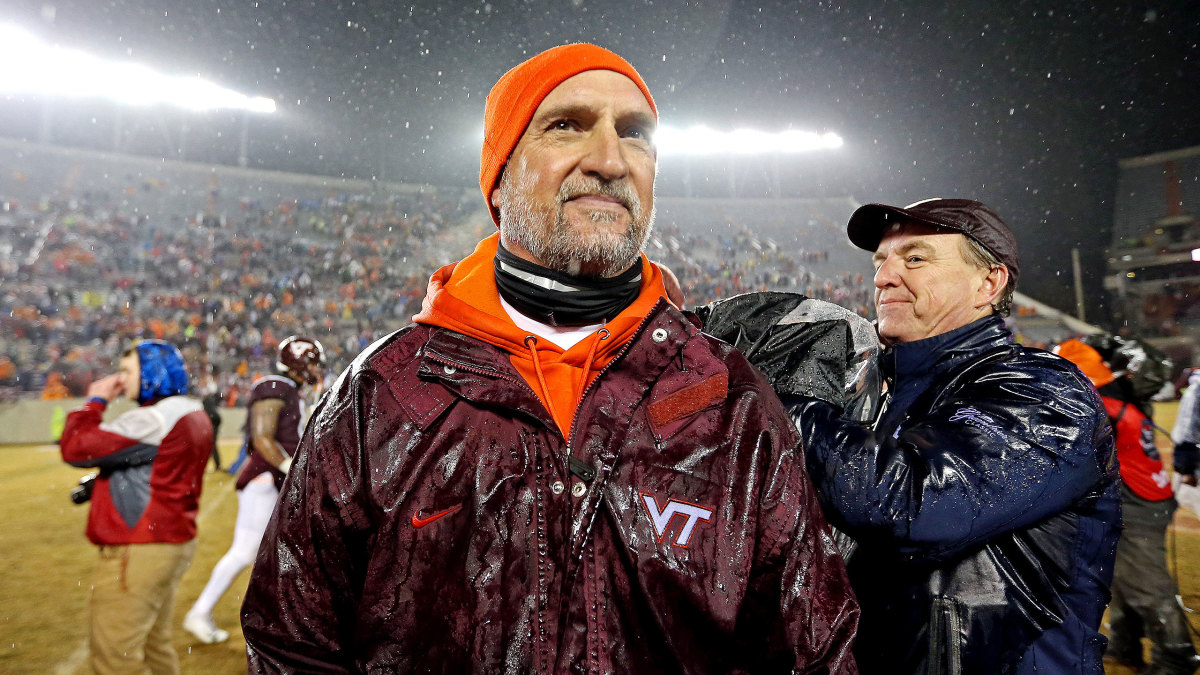

During a news conference here Monday, Foster is chipper. He’s joking with reporters about attending the Hokies basketball game later that night—it’s being play in Maui, Hawaii—and he’s long-winded on his answers, thoughtful, collected and also fun. He’s dressed in gray sweat pants, a long-sleeve Tech T-shirt and on his feet are Nikes dipped in Hokies maroon. His graying beard is closely trimmed, his hair is combed back neatly—but not too neat—and he’s got a hop in his step that speaks to his unit’s most recent performances. The shutouts against Pitt and Georgia Tech are solid enough, but coupled with outings against ranked foes Wake Forest and Notre Dame, the Hokies just might be playing as good on defense as any team in the country. Foster chalks it up to an offense that’s now soaring with new starting quarterback Hendon Hooker and a young defense finally maturing and playing with confidence. “The kids really hung in there,” Foster said. “They took a lot of pride in making sure they do their job and did it for their brother.”

Later while leaning against a hallway wall leading into his office, Foster gave a reporter as much time as he could—11 minutes—and unnecessarily apologized for its briefness. After all, this is a short week and it’s a big game. Foster feels retirement creeping around, like a closing door about to slam shut, but you wouldn’t necessarily know it.

“If we didn’t know this was his last go-around, I don’t know that you’d be able to figure it out,” head coach Justin Fuente says. “(He’s) competitive, fiery and working hard.” Oh, but it’s coming. In a moment of reflection, Bud admits that he’ll miss spring ball more than anything, a time of teaching and building relationships with his players. As for his career, he doesn’t use the word regret, but it’s clear that he has at least one: not winning a national championship for mentor and friend Frank Beamer, the man who hired Foster as a graduate assistant at Murray State, brought him to Blacksburg and, he says, “took care” of him for three decades. “If we could have won a national championship, just because of the person he was and how he treats people, he’d of been instantly put at the top,” Foster says.

If Beamer is worshipped in this town, Foster is praised. Since his retirement announcement in August, Tech has geared its season around Robert, Jr. Foster. We’re doing it all for Bud. This one’s for Bud. Those are common messages heard around this place. The school held a “Bud Foster Day” in a home game against Wake Forest in which it unveiled, to Foster’s surprise, a stadium banner bearing his name and his famed lunch pail, symbolic of his unit’s decades-long blue-collar approach.

After a 36-17 victory over the then-No. 19 Deacons, players doused him in a Gatorade shower and carried him off the field. That day, Beamer publicly lobbied for Foster to be the first ever assistant inducted into the college football Hall of Fame. At the start of the year, the school even added to its website a dropdown tab titled “#ForBud,” linking to some of his career highlights: 35 shutouts, 45 draft picks and 889 sacks, which leads all of FBS since 1996.

“It’s all bittersweet,” says his 33-year-old son, Grant. “Hell of a run, to put up double goose eggs like this.” No one wanted to see Bud go out captaining a group getting gouged, especially not Bud. Tech allowed 35 points in the season opener against Boston College and then 45 in Game 4 against Duke. Through the latest four games, they’ve given up a combined 38 points. “Obviously would I picture this? Is this the way I’d want it? Yeeeeaaah,” he smiles during that news conference Monday.

Bud’s retirement took several by surprise. He’s only 60, but the last few years have felt different. His son sensed it each July when his father left his cherished lake house for preseason camp. Bud wasn’t as excited to return to football as he had been in previous seasons, leaving behind the joys of Claytor Lake: the sunrise from the back porch, wake-surfing behind his ski boat, fishing for bass on his little skiff. “If I’d say that if anything turned him to retirement it’s the fun we have at that lake house,” Grant says.

But there is more to this story. Over the last few years, Bud began to battle extreme amounts of stress, dating back to the final seasons of Beamer’s run at the school. Heart issues crept up, stemming from a workaholic lifestyle, sleep apnea and an investment in his unit’s production that can at best be described as extreme. Last year, things got serious when, during preseason camp, Grant rushed to campus to transport his father to the hospital for dehydration, among other issues. Later on, Tech slogged to a three-game losing streak in which Bud’s unit gave up 49, 31 and 52 points, the latter a Nov. 10 loss at Pitt that sent him into an extreme bout of atrial fibrillation. AFib is the most common type of irregular heartbeat, an abnormal firing of electrical impulses causing the top chambers in the heart to quiver and sometimes leading to stroke.

“This business can do that,” Bud says. “Part of it is, I’ve been in a lot of fourth quarters, a lot of tight battles. I hold lot of expectations, more self-driven than probably what we’ve created here. When we don’t play at a high level or don’t execute, I take that personal. We gave up over 500 yards rushing against Georgia Tech and Pitt. We don’t do that here.” In hindsight, football nearly killed Bud. In a way, he saved himself. He didn’t need the defibrillator. From his hospital bed, Bud’s jerk of his upper torso immediately lowered his heart rate from 210 to 180, a stunning turn of events that he and doctors can’t really explain. “It was just the motion,” he says. “Maybe it got some of the fluids and medicine kicked into my system.”

Jessie refers to the incident as a mental shift in Bud’s life, a turning moment when his three children and four grandchildren could have lost the patriarch of the family. Bud has managed his heart condition this season with medication—two pills per day—but he wants to take no chances. In a way, he's got a second life to live. Bud, a divorcee, married Jessie in February on Super Bowl Sunday, about four months after the hospital scare and around the time discussion began about him retiring. Jessie has three boys of her own from a previous relationship, the oldest a junior in high school. When they both become empty nesters—Bud has been one for more than a decade— they plan to travel to world. Already Jessie has purchased a bucket list book and made plans for trips this offseason: first to Key West in January, then to Cancun, Destin and Italy.

There are other reasons to call it quits, too. Bud wants to spend time with his grandkids, the oldest 11 and youngest 3 weeks, all of whom live in easy driving distance. He wants to chill at his lake house, where Jessie and him plan to permanently move in the next few years, and he’s hoping for the first time next August to celebrate his son’s birthday without having to maneuver around camp.

For now, Bud is so focused on the season that Jessie believes her husband hasn’t processed actual retirement, and she’s unsure of when that’ll happen. “He’s so wired and methodical and his focus is so concentrated that I think at this point he’s just moving on to the next game," she says. “It will be interesting at the end of the final game. I don’t know if it will settle in.”

Bud’s focus is so excessive that Jessie had to remind him to be chill during Bud Foster Day, leaving him a handwritten note in the team hotel with the message “Be in the present.” Bud’s intensity is why he is perceived to outsiders like he is—a grouchy, old football coach. He is quite the opposite, bubbly and upbeat, friendly and sentimental. Jessie has never seen Bud turn away an autograph-seeker. He does know how to relax, even away from that lake house. Maybe it’s a cocktail or his favorite candies, Smarties. He keeps bags of the sugary tablets under his desk, gifted to him by his family each year for his birthday. Bud is such a darling here that his favorite mixed drink is a menu item at a local hotel in town. At the Hyatt Place Blacksburg, one can order The Bud Foster: double Tito’s, tonic, fresh lime and apple juice with a splash of cranberry, created by bartender Liz Tabulous. “He knows the owners real well and the whole bar staff. He’s always great to all of us,” says Jeremy Fernandez, a senior at Tech who works at the hotel’s front desk. “People always come up to him, ‘Oh you’re Bud Foster!’”

How could Bud leave this place? He’s really not. He’ll remain in an administrative role in Virginia Tech’s athletic department, likely attending most if not all games. Can you imagine this man watching a game from a suite without headsets? His son can’t. “If he turned around tomorrow and signed a four-year extension, it wouldn’t surprise me,” laughs Grant. “I worry about him to an extent. Work 17 hour days and then retire. What do you do with yourself? He’s a routine guy.” For one last game at least, Bud Foster will patrol the Virginia Tech sideline, and it’ll come with a championship on the line against a bitter rival that he’s dominated for decades.

Virginia and its quarterback Bryce Perkins pose big problems. He threw for more than 250 yards and rushed for more than 100 in Tech’s 34-31 overtime thriller over the Cavaliers last season, a victory that extended the Hokies’ win streak over their in-state foe to an incredible 15 years. Foster has faced Virginia all 32 seasons he’s coached in Blacksburg. Against Foster’s defenses the last 23 seasons—he began as coordinator in 1996—Virginia is averaging 15.1 points a game. In those games, the Cavaliers are 3-20.

There is pressure on both sides. Bronco Mendenhall, in Year 4 in Charlottesville, is attempting to snap not only that 15-game skid but a streak of ACC division championship bouts lost to the Hokies, in 2007 and 2011, both at home like this one. Meanwhile, Tech and Fuente are focused on extending the stranglehold they’ve had on their rival—while, of course, wanting to usher out the Bud Foster era in fitting fashion: another defensive thumping of UVA. So far, this November has been a dream end to a stunning career: a 19-point victory over a ranked team on Bud Foster Day, a 45-0 whipping at Georgia Tech, a 28-0 stomping of Pitt. Is there more left? During Monday’s news conference, Bud lets his imagination run wild. “Now,” he said, “what would be really perfect is if we’d go out and shutout this crew and then go shut out Clemson. It would be like kissing Cinderella.” The fairytale isn’t necessary. Here in this place, Bud Foster is already a prince.