Meet Sam Nader—The Man Behind LSU Football for the Last 45 Years

BATON ROUGE, La. — Will Muschamp is attempting to eat dinner while analyzing film of South Carolina’s next opponent, undefeated and No. 3-ranked Clemson, when he receives an interview request through text message. Few topics can take him away from football and food, but this is one. “You’re doing a story on Sam Nader?” says Muschamp, Carolina’s head coach and a former LSU assistant. “It’s about damn time someone did.”

You probably don’t know Sam Nader and maybe you’ve never even heard of him (that’s the way he likes it, honestly), but for more than four decades, Nader has labored in the darkness here at LSU, silently and diligently, unassuming and inconspicuous. He is the man behind this football program, a living connection to the past, a confidant for thousands of players and a consigliere to dozens of coaches. He is the grandfather of this place, having just completed his 45th consecutive regular season as a member of the LSU staff. He’s a survivor in a cutthroat industry, outlasting nine head coaches and six athletic directors, nine times retained through coaching transitions, an untouchable man, bulletproof really.

Since arriving at the school as a graduate assistant in 1975, Nader has been on the sideline for 509 games, 14 division, conference and national championships, with two perfect regular seasons (2011 and 2019). He’s seen Tiger Stadium expand four different times, and he’s worked out of four different office buildings. He’s even been here long enough to remember when the school still situated its snarling live Bengal Tiger in front of the visitor’s locker room.

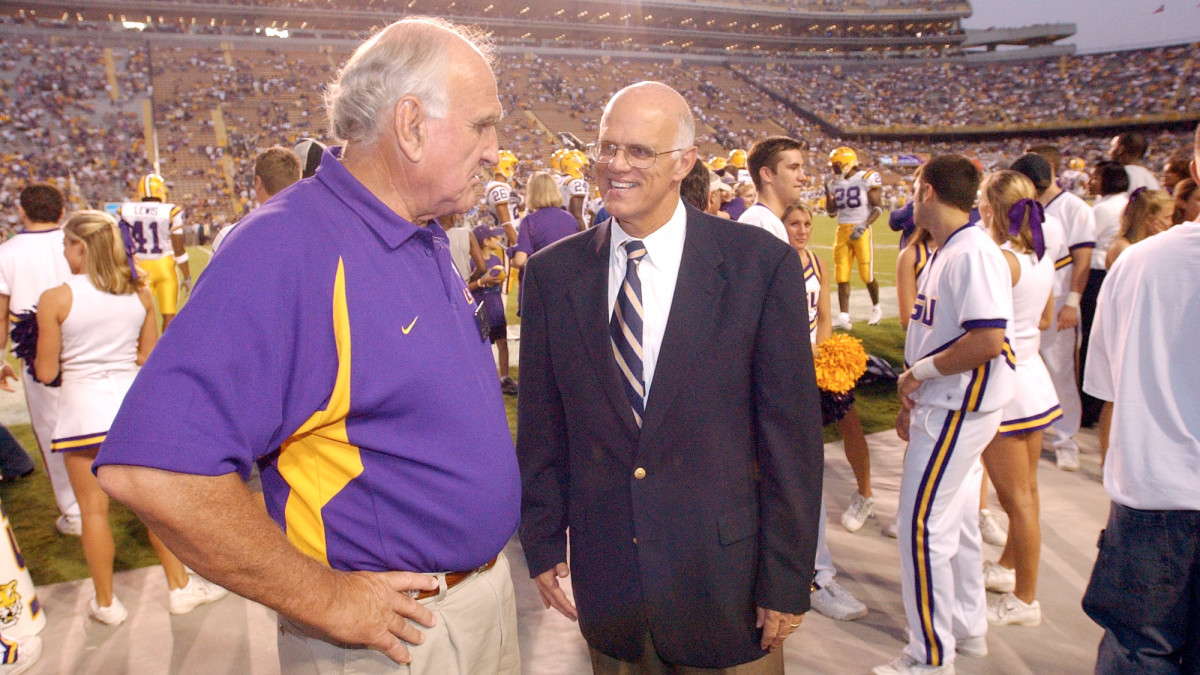

While all around him this place has changed, Nader has remained mostly the same, right down to his spectacles and balding head, corroborated by photographs from the 1970s. “I don’t remember ever having hair,” the 74-year-old quips. Words slowly tumble from Nader’s mouth in a soft hum. A noticeable country twang underscores one of the friendliest, warmest voices you’ll ever hear, its roots surely traced to his father, a traveling Methodist minister in Louisiana and Texas. For nearly a half-century here, Nader has managed to dodge much attention, often going to great lengths to avoid the media, not out of rancor but modesty. Contacted earlier this week, he encouraged a reporter not to “bore” his readers with such a ridiculous story, even suggesting two other ideas to replace this one. “That sounds like dad,” says Breaux Nader, Sam’s oldest of three children, cackling with laughter at his father’s antics.

Sam is spoken of here as royalty. His reputation is such that some of college football’s most noteworthy men returned phone calls midseason to heap praise on him. “I don’t know that there’s many more like Sam,” says Kansas coach Les Miles, who spent 2005–2016 in Baton Rouge. “He’s an original. He’s one of a kind.” An institution, they call him. Patient, consistent, genuine, kind, loyal, all words used to describe a man whose passion is this place.

Though it’s difficult to determine such, Sam may be the longest serving football staff member in the country. He’s certain to be one of the longest, his tenure spanning eight U.S. presidents. He has no plans for retirement, but Sam does believe that Ed Orgeron will be the final head coach at LSU for whom he works. So as the 12–0 and second-ranked Tigers barrel to a meeting against Georgia in the SEC championship game, it’s time the country learned about the man behind this program. “I told him the other day, ‘Whenever you retire, they’re going to dip you in bronze and stand you outside the building,’” says Justin Vincent, the former LSU running back who now works for the school’s fundraising arm. “I look at Coach Nader like I look at Mike The Tiger—he is LSU.”

*****

Sam Nader begrudgingly agrees to an interview at a local coffee house he frequents each morning. They know him here, his name and his order. Highland Coffees sits on the edge of LSU’s campus, tucked amid student-heavy housing and booze-filled bars. Sam is normally the oldest one here—by about 50 years. “The coffee is the best in the city,” he says. He refuses to drink any other coffee and that includes the free stuff available at LSU’s football operations center. Sam can be forgetful, so it’s quite common to find a misplaced Highlands plastic cup around the LSU facility—next to the fax machine, in the microwave, atop the refrigerator. Everyone knows the protocol. “You just put it back on his desk,” says Emily Dixon, a support staff member working with the Tigers’ offense.

Each morning, Sam stops here for his cup of Joe. He’s a routine man, up by 5:45 a.m. every day, swimming at the LSU natatorium by 6:30 a.m. and then here at Highland Coffees before driving to the office. There aren’t many who beat Sam into the office or leave before him. He might be 10 years beyond normal retirement age, but Sam is no slouch. He had both hips replaced in the spring and returned to work after just a couple of weeks, resisting the urge to use a walker or cane at the facility. Five years ago, in an effort to motivate the team during a 30-degree outdoor practice, Sam showed up shirtless with a purple ‘T’—for Tigers—painted across his 69-year-old chest, a photo of which went viral in the LSU community.

Sam is old school. As if it’s not enough that he uses a No. 2 pencil, Sam often makes calls by actually punching the digits into his phone as opposed to scanning his contacts. He’s a traditionalist too, growing fussy when the Tigers occasionally play in alternate uniforms—he likes the classic. Sam addresses the team from time to time, usually opening his speech in the same way he would have in 1977: “Gentlemen of the Gridiron,” he normally begins. Surrounded by teenagers and 20-year-olds, Sam is an easy target for playful lampooning. Those who played at LSU in the 1990s used to call him Fire Marshall Bill, a popular character portrayed by Jim Carrey on the comedy show In Living Color. “We had to explain to him where it came from,” laughs former running back Kevin Faulk, now in a support staff role with the team. “He checked it out. He was like ‘Man, that does kind of look like me.’”

Sam grew up in Louisiana, along the Texas border in both Lake Charles and then later Shreveport. He’s a father of three and a grandfather of six. In 1975, the Naders moved to Baton Rouge from Columbus, Ga., where Sam coached prep football after a stint as a backup quarterback at Auburn. He first appeared in the LSU media guide in 1979 as the “junior varsity coach,” the first of many titles he’s held through the years: recruiting coordinator, administrative assistant, director of football operations and assistant athletic director for football operations. While the titles have changed, Sam’s role has virtually remained the same: He oversees everything that is not conducted on the field. In other words, “He knows where all the bodies are buried,” says former LSU defensive lineman Booger McFarland, now an ESPN Monday Night Football analyst.

Through the years as football budgets and staffs have expanded, Sam has delegated duties. He’s done and still does a little bit of everything. Make bed-checks at 11 p.m. before games? Sam’s done it. Coordinate recruiting trips and organize the walk-on program? Done those too. Arrange summer jobs for players, bus dining hall tables and oversee academic eligibility issues? Done, done and done. Deliver to the team an impassioned motivational speech before a game against Alabama? This year, Sam did that as well. “It was legendary,” says Tommy Moffitt, the Tigers longtime strength coach. “He sounded like Steve Sabol up there from NFL Films.”

In a hotel room on the Friday night before LSU met Alabama in Tuscaloosa this November, Sam addressed the team in a production that some believe inspired LSU’s 46–41 skid-snapping victory, the first in eight tries against the Crimson Tide. Sam highlighted about a dozen of LSU’s historic wins over Alabama, showing clips of them on a projection screen and paralleling those teams to this one. Some of the videos were black and white, dating back to the 1970s. “He wanted to show us that we are capable of getting the monkey off our back,” says LSU punter Zach Von Rosenberg. “I think that’s why we played so loose.”

*****

Gerry DiNardo had no real plans to retain many people on LSU’s former football staff when he took over in 1995. Curley Hallman had won 15 games in four years and been fired days earlier. Why in the heck would he keep any assistants at all? “When I got there,” DiNardo says, “the AD, Joe Dean, said, ‘We’ve got a guy Sam Nader, been here a long time. If you don’t like him, you’ll be the first person I’ve met who doesn’t.’ It was Joe’s way of saying, ‘You’re keeping Sam.’”

DiNardo became the fifth different LSU head coach to retain Sam, and he realized days later why Dean recommended it: Sam was good. Sam has been an advisor and organizer for the 10 head coaches under which he’s worked, some of his most important work coming as a recruiter during transitional periods from one coach to the next. Sam helped secure a 1984 signing class that eventually delivered an SEC championship, had a significant influence in the Tigers landing prized running back Kevin Faulk and guided Miles, in his first month on the job, through the winding Louisiana roads during recruiting trips, Sam on the other end of the phone giving directions. “I’m not watching where I’m going,” Miles remembers. “He’s saying make a right and a left, and I have to ask again. Make a right and a left. That was for two weeks. He’s a serving man. He has no peer. He’s special.”

Similar to many LSU head coaches, Miles confided in Sam. After a speech to the team, he sometimes privately sought Sam’s approval. How did I do? Is that what they needed? Mike Archer, coach from 1987–90, bounced ideas off Sam and used him to understand the nuisances of coaching at a politically charged place like LSU. “It’s like no other place. It’s unique,” says Archer, now a coach in the upstart XFL. “He could tell you ‘this is the guy you’ve got to go to talk to.’”

Sam’s relationship with Nick Saban ran deep, says Muschamp. Saban coached LSU for five seasons, 2000–04. “Nick trusted him more than anybody, and that’s hard, especially if you’ve been with the former staff. Nick loved Sam. If we talked about anything in the state, he’d get the O.K. from Sam.” In 1998, when Dinardo’s fourth team began declining in performance, the coach asked Sam for his thoughts. What he got was a 10-page long, handwritten letter that DiNardo still keeps to this day, a relic from a bygone era, the cherished work of an unsung legend. “Sam is part of the fabric,” says longtime athletic trainer Jack Marucci. “He’s the hidden gem here.”

The bond today between Sam and LSU’s head coach is as tight as ever. Orgeron privately meets with him to discuss the makeup of the team and personnel. As he’s done for decades, Sam sits in on every staff meeting, and he even sometimes watches film with coaches, silently seated in the back. “Whenever I’ve got to make a big decision,” Orgeron says, “I go to Sam and ask him what he thinks because he’s been around some great coaches.”

Sam is so deeply connected to the high school community in this talent-rich state that a first-year coach would be crazy not to retain him. That doesn’t mean there weren’t close calls. Sam feared in 1984 that he had ruined a chance to remain on staff under new coach Bill Arnsparger. Why? Because he nearly starved the coach while the two crisscrossed the state on a recruiting weekend. On one late afternoon, having had no breakfast or lunch, Arnsparger glanced toward Sam from his passenger seat, “Can we stop for crackers of something?” Welp, there goes that job, Sam thought.

There were other rough patches, even with Saban. The coach once cussed Sam so loudly from his office that it echoed down the hall to Muschamp, who was shaken by the incident, because nobody cusses good ole Sam Nader, not even Nick Saban. “I walk to Sam’s office and say, ‘Sam, you don’t have to take that from him,’” Muschamp recalls. “He looks at me, ‘Will, he’s just having a bad day.’”

Muschamp pauses with a chuckle.

“There’s a place in Heaven for Sam Nader.”

***

Joe Burrow, if you haven’t heard, is from Ohio, and in Ohio, there are no Piccadilly restaurants. So the LSU quarterback didn’t know exactly what to expect when he walked into a Baton Rouge Piccadilly last Thanksgiving Day. He quickly realized that his presence had dropped the median age by about 30 years. “It was lots of old people. And then me,” Burrow says. “I walk in and Coach Nader is sitting there by himself waiting for people to come eat with him.” For any LSU football player without a place to eat for Thanksgiving, Sam Nader annually has a standing invitation for them to join him at Piccadilly, a cafeteria-style restaurant known for its affordability. Last year, Burrow was the only one who showed up. “It was interesting,” says a smiling Burrow.

When former players return to Baton Rouge, the first person many of them want to see is Sam, even if it’s just to hear that molasses of an accent slowly spill from his mouth. He’s an important man in many of their lives, always available, on-call day and night. There is a brotherly bond between a man old enough to be some of these guys’ great-grandfather. In fact, during kicker Colby Delahoussaye’s tenure at the school from 2013–16, he’d often prank Sam during bed-check time, cutting off the lights and instructing the specialists in his room to hide. Sam would flash a light into the room to find empty beds before a bunch of kickers, punters and snappers leaped out from hiding.

Sam has always been ripe for this sort of thing. Back in the 1980s, the Southeastern Conference held a sort-of convention for the league’s assistant football coaches in Birmingham. Every year, the event ended with each SEC staff telling a joke to the entire room. The funniest joke won a cash prize. Each year, LSU appointed one man to tell its joke: Sam. And each year, LSU’s joke was the worst of the lot. “I used to tell him,” recalls former LSU assistant Pete Jenkins, “‘Sam, you’re so damn smart. You tell jokes, but you don’t cuss enough.’ The dang joke was told so bad that we’d never get close to winning. He’d tell the joke and the only table in the room to get tickled was the LSU table because we all thought Sam was funny.”

There is no cussing for Sam. He is deeply religious, a longtime leader in the Fellowship of Christian Athletes. Some around the program have never heard him even slightly raise his voice. Marucci knows how to rattle ole Sam: remove English peas from the buffet line during team meals. He did it once and he learned his lesson. Sam very much likes green peas. “I don’t know anybody that eats peas anymore,” says Marucci. “He’s piling up these peas like he’s not going to ever get anymore. I told our guys, ‘Just put a little bowl out there just for him.’”

Sam is a burger guy, too, says Breaux, a 46-year-old who works at Wells Fargo in Baton Rouge. At home, Sam makes a mean, marinated burger, melting the cheese and toasting the bun from the grill. In typical Sam fashion, he scrubs the dishes afterward. “You hear about people who put others first, but you don’t often meet them,” Jenkins says. “Well, that’s who Sam is.” At the forefront in Sam’s life isn’t football or food—it’s his daughter, Lauren. Lauren is autistic. Most old-timers at the LSU football facility know Lauren well. Since she was a little girl, Sam brought her up to dad’s office, showed her around and introduced her to everyone.

She’s 42 now, but Lauren still has the mind of a child. She lives with Sam and his wife. Sam spends most Sunday mornings with Lauren. They have a routine. It’s first to a French café in town called La Madeleine, the only place Lauren will eat. Next, dad and daughter stop by Barnes & Nobles, where Lauren normally chooses a book to buy that more often than not encompasses some version of a princess. Lastly, the two shop for groceries to bring home for Ann Nader, the matriarch of the household. “Joe Dean used to say ‘Children like Lauren always come with families like Sam and his wife,’” DiNardo says. “Sam could unselfishly give himself like only a great dad could.”

There is plenty more to Sam Nader’s story, like how all of this started—his high school football coach connecting him to Charles McClendon for that graduate assistant job in 1975. Or like that time Sam helped hold together LSU’s football program in 1980 when newly hired coach Bo Rein tragically perished in a plane crash. Darrell Moody, an assistant then at LSU, recalls Sam’s leadership during that turbulent time in Baton Rouge. He manned the ship and kept it from sinking. “He may be as organized as any person I’ve been around,” says Moody, now a senior advisor to Mack Brown at North Carolina. “He told us all where to go and what we needed to do. I’m not sure that Sam hasn’t meant more to that school than 90% of the coaches there.”

Moody pauses. “They put statues up down there, right? They need to put up one of Sam Nader.”