Death of a Heisman Winner: The Fall of Rashaan Salaam

Every year, the Heisman Trophy Trust invites past winners to return for the annual ceremony in New York City, so they can be trotted out for a series of dinners and glad-handing functions. It gives the players a chance to relive their glory days, while the trust uses their collective star-power to further mythologize the trophy. The past winners are stationed onstage every year, as a new member joins their fraternity.

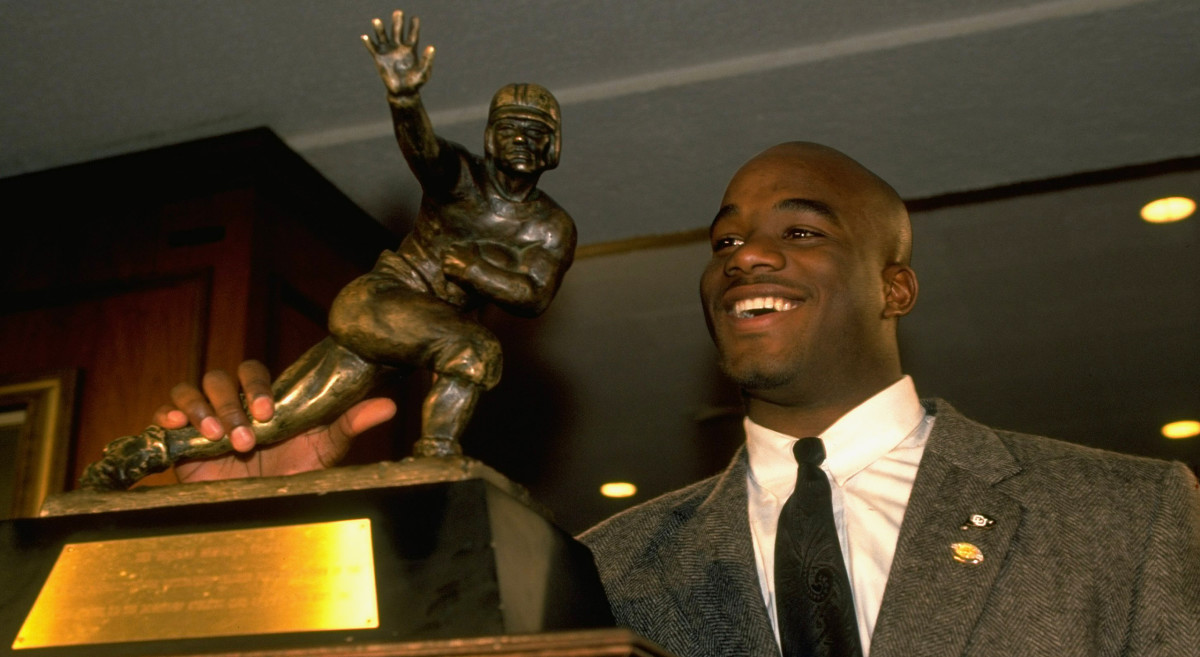

Rashaan Salaam, the 1994 winner, a running back from the University of Colorado, did not particularly enjoy attending the annual gala. At these types of events, people tended to ask, What are you up to? How’re you doing? Questions Salaam did not like answering.

Salaam did not have as much to talk about as the other Heisman winners. He’d often come across articles calling him one of the greatest Heisman busts of all-time. When he signed autographs with the other winners, he told a friend, “Nobody ever comes through my line.” At the ceremony, he often palled around with Mike Rozier, the 1983 winner from Nebraska. After a few drinks, Salaam would open up. “A couple times he told me, he wished he never won the Heisman,” Rozier says. “It was too much pressure for him.”

The Heisman is the highest honor a college football player can receive; it bestows upon the winner great prestige, but also great expectations for their NFL career—and Salaam never lived up to those expectations. In fact, he flamed out of the league rather quickly. Afterward, he told those close to him that he felt like a failure, like he had let them down. He fell into a depression. Then, as he struggled finding his identity after football, the Heisman followed his name everywhere he went, in everything he did. Winning the award turned out to be the best and worst thing to ever happen to him.

Salaam finally returned to the Heisman ceremony in 2014, after staying away for six straight years. A business partner had convinced him to go, to promote a charity they helped run. Salaam attended the event for the final time in 2015; he brought his girlfriend and turned the trip into a romantic getaway. One day, the two of them were sitting in the hotel room when the room’s phone rang. Salaam let the phone ring and ring and ring. Someone was apparently trying to summon him to a private event. After the phone rang some more, Salaam finally blurted out, “I’m not going to that. Nobody wants my f---ing autograph.” Then he led her out and back into the city, without an explanation.

The following year, Salaam did not attend the ceremony. That week, police found his body near a public park in Boulder, Colorado, not far from where he’d played for the Buffaloes. He’d died from an apparent self-inflicted gunshot wound to the head. Salaam is believed to be just the second Heisman winner to take his own life, after Larry Kelley, the Yale end and 1936 winner who shot himself in 2000 at the age of 85, not long after suffering a stroke.

The headline of Salaam’s New York Times obit read: Rashaan Salaam, Heisman Trophy Winner with Colorado, Dies at 42. The trophy followed him until the very end.

***

Salaam grew up in San Diego, raised by his mother and stepfather, who ran an elementary school together. They sent him to La Jolla Country Day, a high school in a well-to-do part of town, where he dominated playing eight-man football, before arriving at Colorado in the early ‘90s as a highly-touted recruit.

The Buffaloes had high hopes for Salaam. He was the son of Teddy Washington (who later became Sultan Salaam), the running back who’d played for Colorado, San Diego State and briefly for the Cincinnati Bengals. Blessed with his father’s genes, Rashaan stood 6-foot-1, weighed about 220 pounds, and had the long, smooth gait of a sprinter. In his junior year, in 1994, he emerged as the best running back in college football. He ran for 2,055 yards and 24 touchdowns, making him the fourth college player to ever eclipse 2,000 rushing yards in a single season, joining Marcus Allen, Mike Rozier, and Barry Sanders.

Reporters flocked to Boulder as Salaam jumped ahead in the Heisman race. But he shied away from interview requests and tried deflecting the attention. He seemed uncomfortable with the spotlight. “I’m scared [of winning the Heisman],” Salaam told a reporter that October. “I really don’t want to win it because I know how much pressure is going to be put upon me. I just want to play football.” They showered him with awards anyway: the Walter Camp, the Doak Walker, the Heisman—the last of which he bequeathed to his mother, Khalada Salaam-Alaji, who kept the trophy on display in her living room in San Diego.

Amid all the banquets and events feting her son, Khalada had taken a moment to soak it all in and say a quiet prayer: Please God, do not let this be the pinnacle of my son’s life.

***

About five years later, Salaam was back in San Diego. His NFL career only lasted about three-plus seasons, roughly the length of an average career. He spent a lot of time waiting for the phone to ring, hoping some team would give him another chance. He’d make comments to his mother: I’m one of the best running backs in the NFL, and I’m sitting here in your living room.

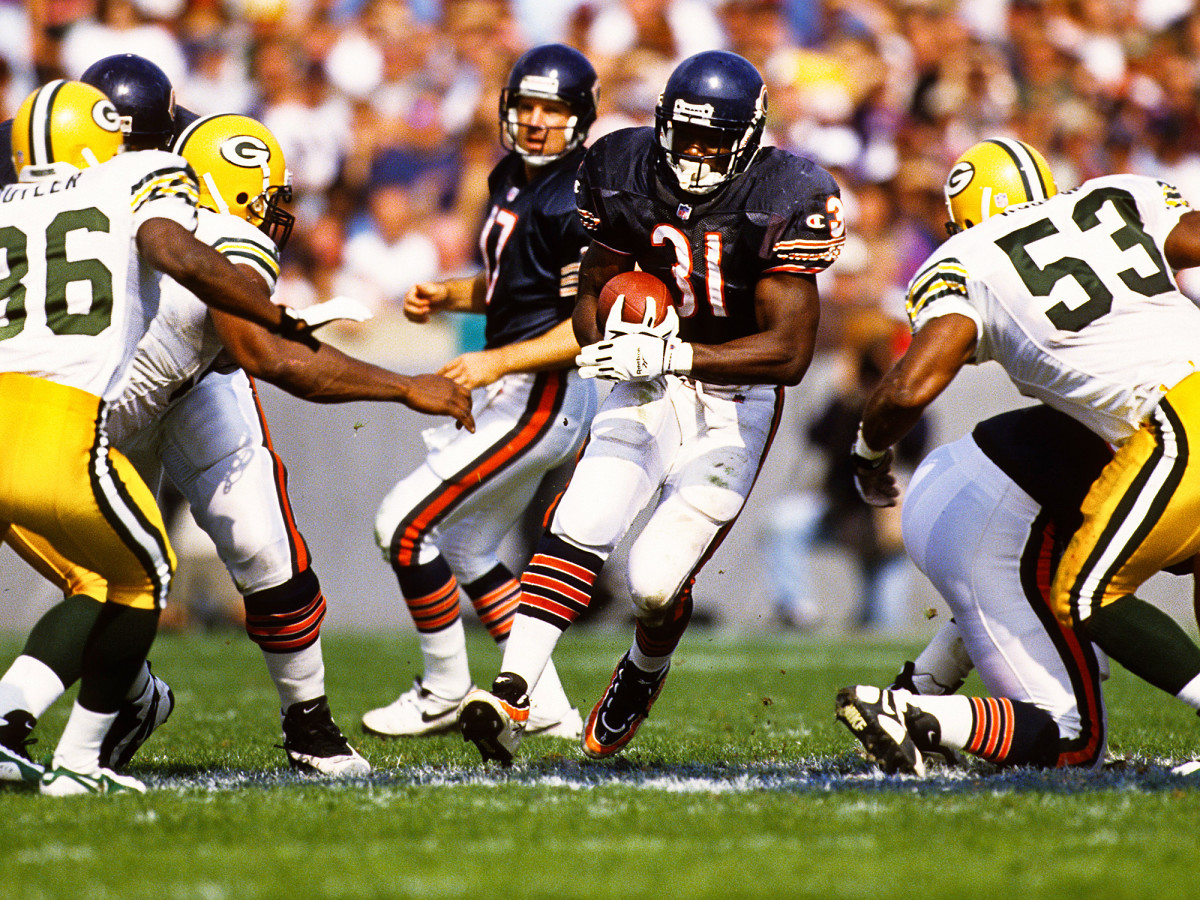

All that waiting gave Salaam time to reflect on his career, and stew on what went wrong. After Salaam won the Heisman, the Chicago Bears drafted him in the first round, No. 21 overall, in 1995. His rookie year, he rushed for 1,074 yards and 10 touchdowns, but also had nine fumbles, an issue that would continue to plague him. Salaam also began to suffer a series of lower-body injuries. In his second year, he had knee and hamstring issues. In his third, he broke his right leg and tore an ankle ligament. During his recovery, he started walking too soon, broke a screw in his leg, and had another surgery. That offseason, the Bears tried trading him to Miami, but he failed a physical. Shortly after that, the Bears released him.

After sitting out the 1998 season, Salaam signed with the Raiders in 1999. Before reporting to the team, Salaam was out one night with Eric Norwood, one of his childhood friends, when they got into a serious car crash. Norwood says Salaam cracked a rib, punctured his lung, and busted his right retina. He missed some practice time, recovering. “It’s through the grace of God that we were still alive,” Norwood says.

Later during training camp, Salaam agreed to sit for a TV interview with Solomon Wilcots, another former Colorado football player who worked for ESPN. The story was supposed to be straightforward: former Heisman winner makes comeback with Raiders. But during the interview, Salaam revealed the extent of his marijuana use in Chicago. He said his drug use had made him “lackadaisical” on the field, hence his fumbling issues, and turned him into an “outcast” off it. After he broke his leg, he said, “it pretty much consumed all my time. … I pretty much spent my time sitting around getting high.” (Separately, Salaam had told a Bears official he believed that weed had numbed his senses and contributed to the setback with his leg. After that, the Bears had helped him enter rehab.) Since it was 1999 and marijuana was still considered taboo, the ESPN interview made national headlines. After the Raiders released Salaam at the end of camp, he told Wilcots he blamed the interview.

Salaam’s career never recovered after that. He bounced around to a few more NFL teams, had brief stints in the XFL and CFL, and then the phone stopped ringing. By the mid-2000s, he was effectively retired from football, a Heisman winner out of work before turning 30 years old, back living in his hometown. “He was always down on himself, just about not being The Man, not making it in the league,” says Blake Anderson, one of Salaam’s Colorado teammates. “And that’s what started his depression, feeling like he should’ve done more.”

Friends and former teammates checked in from time to time, but Salaam wasn’t the type to readily offer up information from his personal life. They knew not to ask certain questions, lest run the risk of angering him. This made it hard to tell how he was really doing.

From the outside, Salaam seemed directionless. It was not entirely clear whether he had a job, or steady income. As one friend put it, “He wasn’t working. He was just kind of hanging out.” His mother urged him to go back to school, get a job, do something productive.

Given his status as a Heisman winner, Salaam often had business opportunities presented to him. For a few years, he worked on a project involving mixed martial arts in China, along with a local businessman named Konrad Pi, whom Salaam had met through a friend. Salaam essentially acted as the company’s spokesperson and made a few trips to Beijing. He gave people the impression that the venture was a success. “But I never saw any tangible evidence of it,” says Jack Mills, Salaam’s former football agent.

At one point, Salaam invested money in an insurance firm, according to his childhood friend Shaunta Baker. But Salaam exited after about a year, when his patience ran out. “He wasn’t really into watching seeds grow,” Baker says. “He wanted the plants fully grown. It wasn’t immediate gratification like he wanted.”

***

After hanging around San Diego for several years, Salaam decided to move back to Boulder, back to the college town where he’d enjoyed his most success. At least there he could market himself as only Heisman winner in school history. Salaam set his sights on a new goal: find a job in the Colorado athletic department, maybe work as a brand ambassador, a fundraiser, or an assistant coach on the football team.

Before making the move, Salaam had preliminary discussions about this with Mike Bohn, the Colorado athletic director at the time. Bohn remembers one conversation they had after a fundraiser event in California, on a long car ride back to San Diego. “We were trying to get a better sense of what was going on in his life and maybe how we could help,” Bohn says. “It was all about trying to find the right fit, the right solution, and identifying a passion that would work for him.” But Bohn stresses, the discussions at that point were in their infancy. “We never had a specific solution where it was like, alright, we’re all in, let’s do this.”

Then in May 2013, facing pressure from higher ups at the University, Bohn suddenly resigned. A few months later, Salaam moved into an apartment in Superior, Colorado, a suburb about 15 minutes from the school. He apparently made this move without having a job lined up and without having many contacts in the athletic department.

Around this time, some of Salaam’s friends started doing some fact-finding on his behalf. One of these people was Estes Banks, a running back who’d played with Salaam’s father at Colorado and later with the Bengals. Another was Hannibal Navies, a former CU player who’d met Salaam through a mutual friend. Navies also had experience in this area. He works with The Trust, an NFLPA organization that helps players transition into retirement.

Navies and Banks both reached out to Colorado officials, separately, and both reached the same conclusion: Colorado was willing to engage with Salaam.

But a few obstacles remained. For one, Salaam had never earned a college degree. Dave Plati, the football team’s longtime sports information director, says that, on his way to winning the Heisman in the Fall of 1994, the school later learned, Salaam had essentially stopped going to classes. After that semester, he left school to prepare for the NFL draft. “He would’ve been easily 50, 60 credit hours short [of his degree], if not more,” Plati says.“Most guys who come back have one, two, three classes they need. Now we’re talking 60 hours—that’s 20 classes.”

Salaam also had a habit of going dark at times, of not returning messages. Plati would reach out to him and not hear back for months. Salaam’s family and friends had similar experiences trying to contact him. “He’d be all in, and then he’d disappear,” Banks says. “The only way I was able to help him, I just stayed with it. I called and called and called. If he didn’t answer, I called again. If you weren’t in that mindset, you’d think he was blowing you off.”

Salaam thought this would all be much easier; he was the school’s only Heisman winner, after all. “He was expecting Colorado to come to him and give him something,” Navies says. “He was waiting for Colorado to lay it out for him and say, ‘Here, you have this [job] and here’s your salary.’ No business works like that. Not just Colorado. … I think there was a disconnect in how he felt things should go, or how he felt they should’ve welcomed him back.”

After Bohn left, it’s unclear if Salaam ever spoke with the Colorado athletic department about getting a job. Rick George, the athletic director who came in after Bohn, says he never personally spoke with Salaam about being an ambassador or a coach. Plati says Salaam never broached the topic with him, either. Lance Carl, the associate AD for business development, did not return messages seeking comment.

Regardless, Salaam told people that he felt hurt by the whole ordeal. “They didn’t welcome him back,” Sultan Salaam says. “After winning the Heisman Trophy, he should’ve been welcomed back. ‘O.K., come over here, do this, do that … whatever.’ That didn’t happen.”

***

In October 2014, about a year after Salaam moved back to Colorado, he hosted a party at Elway’s, an upscale chophouse owned by the Broncos’ general manager and 1982 Heisman runner-up. The event doubled as a kickoff event for Salaam’s new charity and his 40th birthday party. He charged $65 a head, saying the proceeds would benefit the foundation. He promised the attendees appetizers, cocktails, and a birthday photo with him and the Heisman Trophy.

As his hope of working for the University dimmed, Salaam had turned his attention to charitable work. Estes Banks, one of his mentors, had introduced him to Francisco Lujan, a local businessman who connected him to Riley Robert Hawkins, a school social worker who had a fledgling organization called the SPIN foundation, Supporting People In Need. Salaam came aboard as the president and celebrity face of the charity. When he asked his mother to ship him his Heisman trophy, she assumed he needed it for the foundation.

Salaam began making public appearances on behalf of SPIN. He often spoke to children from disadvantaged backgrounds, telling them stories from his career, the highs and lows, things he wished he’d done differently. A few times, he brought the Heisman and let people pose for photos. At one point, Salaam brought about 30 students to Aspen for a week of skiing and personal growth workshops. They branded the outing: “Ski for Heisman.”

Lujan also arranged personal speaking engagements for Salaam, for which they’d charge a fee. When organizers asked Salaam to bring the Heisman to these events, though, he usually refused. He told Lujan it was disrespectful. “If people want Rashaan, they get Rashaan,” Salaam would say. “‘They don’t get Rashaan and The Trophy. Marcus Allen and all these other [Heisman winners], when they do events, do you see them taking their trophies?” Every now and then, he’d joke with Lujan about selling the trophy, if the SPIN foundation ever needed the money. “The trophy’s the trophy, but I’m still Rashaan Salaam,” he would say.

But Lujan felt the charity needed to play up Salaam’s standing as a Heisman winner. Lujan encouraged Salaam to attend the annual Heisman ceremony, to spread the word about the foundation. Salaam pushed back at first, before agreeing to attend the event in 2014.

Those were the type of gatherings that would bring out Salaam’s insecurities. Deep down, his failed NFL career still gnawed at him. He often compared himself to other football players. Watching NFL games made him mad sometimes. “He’d get pissed when he’d see people who he knew who were still playing,” says Anderson, his former college teammate. “We’d be like, ‘Hey, man, you’re not the only one. There are guys out there that don’t make it.’ ”

Salaam told several friends and family members that he felt like a failure, that he had let them down. He told Shaunta Baker he wished he’d never won the Heisman, if only to see how his NFL career would’ve played out without the weight of those expectations. He told another friend if he’d played 10 years in the NFL, he could’ve died happy. “I’m serious,” Salaam said, “if I’d had 10 good years, I’d be good being dead.”

***

Sometime in late 2014, Salaam reached out to Michael Russek, the director of Grey Flannel Auctions, an Arizona-based sports memorabilia dealer. Salaam wanted Russek to broker the sale of his Heisman Trophy. After some initial conversations, Russek flew out to Colorado to meet Salaam in person and pick up the trophy. The meeting lasted all of 20 minutes. Salaam did not tell Russek specifically why he wanted to sell the trophy. “He needed the funds to further some of his other projects,” Russek recalls. “I didn’t have the feeling that he was pressed and really needed [to sell it] more than anything else. He just wanted to go in a different direction is what it seemed like. He was really level-headed, unemotional.”

With that, Russek brought the trophy to the airport and flew it back to Arizona. It sat on the seat next to him on the plane, all packed up to avoid drawing any undue attention.

***

Around early 2015, Salaam was attending a talk at a local church when he bumped into Shelley Martin, a classmate from his CU days. They soon started dating and Salaam dove into the relationship headfirst. He talked about marrying Martin someday and doted on her two daughters as if they were his own. Martin lovingly referred to him as “Papa Bear.” In December 2015, Salaam brought her along to the Heisman ceremony, turned it into a vacation. “Best trip of my life,” she says.

One day shortly after they returned, though, Salaam became violently ill. “He was just vomiting all night long,” Martin recalls. “I mean, it was like every minute.” She took him to urgent care and then to a hospital, where they had him on an IV for about half the night.

In the ensuing months, these vomiting spells became more frequent. “Too many, I can’t even count,” Martin says. “It was our new normal.” She suspects he might’ve been dehydrated, but doesn’t know for sure. Sometimes he complained of having bad headaches. On a few dates, he showed up on crutches saying he had gout. Salaam didn’t go into detail, and Martin didn’t ask questions. She just knew he was in pain, physically and emotionally.

When Salaam and Martin spent time together, he dropped clues about his mental state. Unbeknownst to her, in early 2016, Salaam told his stepmother he’d been diagnosed as bipolar and he’d begun seeing a therapist. When Salaam and Martin watched football, he would make comments: Oh, that’s who you should’ve had in college. He’s a millionaire! You deserve a millionaire. Once when he was watching the movie Concussion, he screamed at the top of his lungs, “This is some bulls---!” He didn’t elaborate on or explain the outburst.

The situation with CU still bothered him, too. Salaam complained to Martin that Heisman winners got “treated better” at other schools. He had taken note when the University of Texas hired Vince Young, its 2005 Heisman runner-up. At one point, Salaam told John Reid, a philanthropist involved with his charity, that he regretted moving back to Colorado. “He went on a rant about being dissed and [Colorado] not reaching out to him with open arms,” Reid says. “He just felt like they disowned him. I think how he was treated caused him to lapse into a level of depression, feeling as though he was no longer worthy.”

It didn’t help that Salaam’s business ventures didn’t appear to be thriving, either. His work with the SPIN foundation slowed down, in part, due to funding issues. He had started a business leasing equipment to CBD companies, working alongside Konrad Pi, his former partner from the China MMA project. But Pi says that their business was “slow,” too. Salaam also talked about a real estate project and about opening a sports bar. But he told one former teammate, around May 2016, that he only had $20,000 left to his name.

“[His businesses] never turned out the way he wanted them to,” says Hannibal Navies, the friend who works for the NFLPA organization. “He felt like people were trying to take advantage of him and his name. I think he had a hard time trusting people after a while, because things would never turn out the right way. Then he just became more closed in. It became a spiral.”

That fall, Salaam began isolating himself even more. He pulled away from Martin and turned down friends’ invitations to attend Colorado games. When people stopped by his home, he wouldn’t answer, or it might be 10 minutes before he came to the door. When Navies visited Boulder for a football game, he dropped by Salaam’s place and they chatted for about 30 minutes. Salaam seemed normal—happy, in fact. On his way out, though, Navies spotted Salaam’s handgun resting on his Bible, out in plain sight.

***

On the first Friday of December, 2016, Martin reached out to Salaam to make plans for the weekend, and he started on a rant about wanting to watch college football. “He yelled, ‘I’m just tired of everything, and I just want to go kill myself!’” Martin recalls. She went into hysterics and only calmed down once Salaam assured her he was going to watch football with a friend. “Like everything was O.K.,” Martin says.

On Sunday, while hanging out with Konrad Pi, his business partner, Salaam asked if Pi would cover a debt for him. Salaam said he owed some people $1100 and that he only had about $400 remaining in his bank account. It appeared he needed help paying his rent.

Around this same time, Salaam spoke with Tim James, another former Colorado player, and talked at length about a local businessman he’d befriended named Mark Ray. Years later, Ray would be investigated for running a Ponzi scheme before reaching a settlement with the SEC.

On Monday night, a few days before the 2016 Heisman ceremony, Boulder police found Salaam’s body in a local park, laying next to a parked car that had its engine running. Inside the car, Salaam had left behind an opened can of Ginger beer, an opened bottle of vodka that appeared to be mostly full, and a glass pipe that appeared to have been used, along with some marijuana. An autopsy later revealed that Salaam had THC in his system and a blood-alcohol reading of 0.25, more than three times the legal driving limit.

In the aftermath, many people assumed Salaam must’ve had CTE. Jabali Alaji, Salaam’s brother, told USA Today he suspected his brother suffered from the neurodegenerative disease. Jabali said Rashaan had all the symptoms: anxiety, depression, apathy, memory loss. But the family declined to excavate Rashaan’s brain, citing their Muslim religion.

Others pinned Salaam’s death on mental illness. After another Colorado football player, Drew Wahlroos, died by suicide less than a year after Salaam, Buffs4Life, a charity that supports former CU athletes in need, shifted its focus to mental health issues. “Everyone attributed it to [CTE],” says Khalada Salaam-Alaji, Rashaan’s mother. “But I attribute it to depression, mental illness, just being fed up. Just stepping out and stepping away.”

This Saturday, Khalada will attend the Heisman ceremony, to commemorate the 25th anniversary of her son winning the award that sat in her home for all those years. Only after Salaam died had his family discovered the trophy was missing. His mother thought it’d been stolen, until about a year later when she saw it up for auction. The seller was promising to donate the net proceeds to support research of athletes’ medical conditions, including CTE, and it eventually went for nearly $400,000. At one point, Khalada attempted to retrieve the trophy. She made a few calls, then decided to stop. She isn’t sure she could’ve looked at it every day.

In Salaam’s pocket he had left behind a handwritten note: “Some days good - Some days bad - F--- Rashaan Salaam - Don't be sad!! - No funerals please.” The police found a second note in the car, behind the driver’s seat: “No funerals wakes memorials let me be in peace!!"

***

The organization Buffs4Life continues to help former Colorado athletes in need, especially those with mental health-related issues. For more information on how to support its cause, please visit Buffs4Life.org.