Man of the House: How Clemson's John Simpson Made Himself an All-American

CLEMSON, S. C. — On the day last week when John Simpson became the first member of his family to graduate from college, he took time to send a text to a man four hours away—not a relative, but someone who played a vital role in helping the Clemson All-American offensive lineman reach this milestone.

Tommy Hall, proprietor of Halls Chophouse in Charleston, needed to see what Simpson had accomplished. So Simpson sent Hall a picture of his brand new diploma, and Hall in turn sent the picture to everyone on his staff at the upscale steakhouse.

“They’re all so proud of him,” Hall said. “We love watching him. It makes you proud to see him succeed.”

His path to football stardom, a college education and likely becoming a high NFL draft pick next spring wound its way through the kitchen at Halls, an institution in the Southern food Mecca of Charleston—and a restaurant Simpson and his family couldn’t afford when he was growing up in the rougher north side of the city. But opportunity met necessity in ninth grade, when Hall was visiting local high schools looking to hire teenagers who weren’t planning on going to college. It was part of the outreach program called Teach The Need, aimed at providing a restaurant-skills curriculum to low-income kids in the area.

Whenever Hall worked with high school students, he left them with this invitation: “If you want a job, come see me.” They rarely did.

“You’d be amazed how many people wouldn’t come see me,” Hall said. “Jonathan did.”

And so Halls hired its first high-school employee from the Teach The Need program. A relationship developed, and a mentorship formed.

Simpson was only 15 years old, but he already had been taught the value of work by his grandfather, also named John Simpson. And money was chronically scarce at home, bills piling up without being paid, creating a palpable familial stress.

“I’d sit in my room and cry,” Simpson said, recalling difficult days as an adolescent—his father in prison, his mom working hard but struggling to make ends meet for her two sons, John and Jayden. “I felt like it was all on me to be the man of the house.”

This is how he went about being the man of the house at a tender age—taking a job in addition to going to school and playing football. They taught big John Simpson how to tie his black tie with his white dress shirt, and how to work as a bus boy, food runner, server and greeter to the high-end clientele at Halls.

For three years, Simpson worked whenever he could around his football and wrestling schedule. Sometimes he worked the night after playing games, coming in with cuts and scrapes on his hands and arms. The Halls staff bandaged him up and he did the work—putting his long reach to work at the bigger tables, and applying his natural people skills to charm patrons.

“I’m always willing to talk to people,” Simpson said. “That’s just being myself.”

Said Hall: “He had a smile that lit up the room. Great character. He was a teammate for everybody. Great charisma.”

Simpson developed during that time into a four-star college prospect, with schools from all across the South courting him. The decision “weighed on him hard,” according to Hall, who suggested he visit Clemson. Simpson narrowed his choices to Florida, LSU and Clemson, not committing until 2016 signing day.

Four years later, Simpson is one of the great success stories in a Clemson program littered with them.

“He’s a big ol’ teddy bear,” coach Dabo Swinney said. “One of my favorite kids I’ve ever recruited. He just has such a sweet spirit. But man, is he a good player.”

Good enough that Swinney expects the 6-foot-4, 330-pound Simpson to be the highest drafted offensive lineman of his 11-year head-coaching tenure at Clemson. (The school has produced an annual litany of draft picks at virtually every position but offensive line. The Tigers haven’t had one selected at all since 2014, and amazingly haven’t had one picked higher than the third round since 1971.)

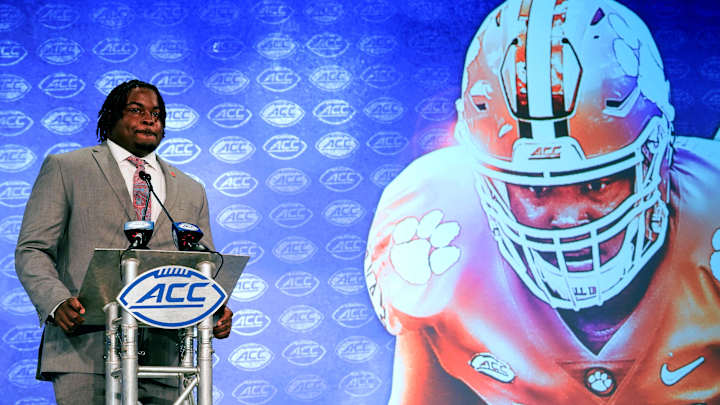

Simpson has a pro-level mix of power and athleticism (he was a standout wrestler in high school), plus the requisite nasty streak for the trenches. But those abundantly clear strengths aren’t the biggest reason why he was the leading vote getter this year when his teammates elected captains. Nor are they the reason Simpson was elected as Clemson’s offensive representative at Atlantic Coast Conference media days in July—where he showed up wearing a blonde wig, an homage to star quarterback Trevor Lawrence, by far the more well-known Clemson Tiger.

No, the reason John Simpson is so respected and beloved by his teammates is attributable to the subtle steel that kept him from breaking in some difficult times. As much as anybody, he has been the man of the house for Clemson football.

--

“Look for us in Arizona,” grandfather John Simpson quipped. “We’ll be in the Suburban with Clemson flags.”

The family members who helped forge the resilience and character within No. 74 for the Tigers have driven damn near the entire expanse of America this week to see Simpson and his Clemson teammates play Ohio State Saturday night in the Fiesta Bowl.

The Suburban was rented Monday by Keyonna Snipe in Charleston. On Christmas Eve, she and a crew of friends and relatives drove 2 1/2 hours north to Rock Hill, S.C., and spent the night with her former father-in-law, John’s grandfather. At 4 a.m. on Christmas morning, they set out from Rock Hill for Arizona.

The plan was for a great uncle to take the leg across Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi and Louisiana, to the Texas border. Then the eldest Simpson, a trucker by trade, was going to handle all of Texas. They would figure out New Mexico and Arizona later.

Estimated driving time: 30 hours.

But, hey, it’s nothing the family hasn’t done before. When John was a freshman in 2016 and Clemson was playing Ohio State in the Fiesta Bowl in another playoff semifinal, they made the drive. Last year, for the Cotton Bowl semifinal against Notre Dame in Arlington, Texas, they also drove.

Snipe hates to fly. But there is no distance large enough to keep her from seeing her boy play football, so off they went, burning up Interstates 20 and 10 across the southern United States.

“My mom is my rock, man,” Simpson said. “I would do anything for her, and I know she would do anything for me.”

Among the other things Snipe will do for her boys, in addition to cross-country driving: working the third shift assembly line at Cummins Turbo Technologies, making parts for turbocharged engines.

Third shift factory work isn’t the most glamorous of lifestyles, but it does pay the bills. And frankly, Snipe said she’s had worse jobs before. In her current position she and John have most of their phone conversations while Keyonna is driving home from the factory early in the mornings.

“I haven’t been able to afford the best,” she said. "But he was happy with whatever I bought him.”

When John was younger, his rock often turned to the man she described as her rock, John Simpson Sr., for help. Although she was separated from the elder Simpson’s son, John Jr., she has long considered John Sr. to be her father figure.

“My mom passed two years ago,” Snipe said. “I never had my father in my life. He’s just the best. He’s not my father, but he is my father. He has never left our side.”

This was a vow John Simpson Sr. made. He took it upon himself to do everything he could to end—or at least interrupt—the generational problems that had beset the males in his family.

John Sr. got out of prison in South Carolina in 2000. His son, John Jr., was finding trouble with the law as well. John Sr. made a vow to be a positive presence in the lives of his 11 grandchildren—10 girls, and young John.

“I was real messed up,” John Sr. said. “But me being sick and tired of being sick and tired, I had to do something about it. I got down on my knees and prayed.”

What came thereafter was an annual summer pilgrimage—all the grandkids came to John Sr., and worked in his lawn care business. Those old enough cut grass. The younger ones—as young as 4 years old—picked up trash.

“I was trying to teach them about hard work and to earn their way,” Simpson Sr. said. “At the end of the summer, I would take them shopping before they went back to school. We would buy school clothes with the money they earned.”

He also bought them all a pair of shoes for Christmas. The quality depended on the quality of their academic work.

“If their grades were good, they got to pick the shoes,” he said. “If they weren’t good, I picked the shoes.”

During those summers, John Sr. would take his grandson to see John Jr. in prison in North Carolina. The visits were heartbreaking for young John.

“That was real hard,” he said. “I remember leaving (prison), crying my eyes out. I didn’t know the next time I’d see my dad.”

What got him through?

“Football,” he said, then laughed. “Football got me through.”

Back home in North Charleston during the school year, the family was barely getting by in the Dorchester-Waylyn neighborhood, a dangerous area. The Charleston Post & Courier described it thusly in 2018: “In a state that is one of the worst in the nation when it comes to number of gun deaths, North Charleston is one of the most dangerous areas in South Carolina and Dorchester-Waylyn is one of the most dangerous areas in North Charleston.”

Snipe moved her boys out of that neighborhood when young John transferred to Fort Dorchester High School, a decision that provided a springboard for his football career. John Sr. recalls getting a call from his grandson telling him how much he liked the new school and its football program, which provided two pairs of shoes for its players. For once, his grandfather wouldn’t be left trying to special-order (and pay for) size-17 cleats.

But an improved athletic situation wasn’t a familial cure-all. There was lingering bitterness.

“It was difficult for him when he was younger,” Snipe said. “Kids want their fathers. He reached a point where he didn’t want anything to do with him.”

Today, though, with so many obstacles overcome and perspective gained, the bitterness is dissipating.

“My relationship with my dad has gotten better over the years,” Simpson said. “I had to forgive. I’m not going to say it wasn’t his fault, but everyone needs forgiveness.”

--

Life was coming at John Simpson fast last week—past, present and future all colliding in an emotional mashup that has the customarily jovial big man suddenly sweating through his gray shirt and waving a hand in front of his watering eyes.

Present: The All-American offensive guard was sitting in the Clemson indoor facility, as the Tigers prepare for the game(s) that will conclude his college career. It was two days before graduation. Future: The possibility of life-altering money—the kind his family has never had—looms in 2020. Past: He is talking, with remarkable candor, about breaking a generational cycle of incarceration for males in his family, blazing a new trail academically, becoming a beloved part of a championship football program.

And about the burden of being the man of the house while still a boy.

“I still feel like that sometimes,” he admitted.

But what a man he’s become.