One Striking Moment

It was at the beginning of a rare quiet period on the college basketball recruiting calendar that Jamill Jones made his way to New York City on August 4, 2018. Equally hard to come by were the coveted tickets he held to see Hamilton on Broadway that night. He couldn’t have known the drama that was to unfold.

An assistant at Wake Forest, Jones, 35, had spent July pitching high school prospects on the virtues of playing for coach Danny Manning in the ACC, but now he was looking at five weeks, by NCAA rules, with no in-person contact. To celebrate the break he flew north from Winston-Salem, N.C., to visit his fiancé, Djenane Paul, herself an assistant athletic director at Fordham. The couple had tickets to Lin-Manuel Miranda’s hit musical, and they caught the evening performance at the Richard Rodgers Theatre with friends and family. The last song they heard was “Who Lives, Who Dies, Who Tells Your Story.”

Jones and Paul continued afterward to a Times Square lounge. Jones, a teetotaler, says he had only a ginger ale. Around 1:30 a.m. he drove his fiancé’s white BMW X3 across Manhattan and into Queens, where he’d reserved a room at the Courtyard Marriott in the Dutch Kills section of Long Island City, on a gentrifying street that sits in the shadows of a burgeoning outer-borough skyline.

Eleven blocks away at the Foundry, an event space evolved from industrial origins toward millennial revelry, another type of celebration was winding down. Over the previous six hours, 35-year-old Sandor Szabo, a vice president in digital marketing and advertising, had fêted his stepsister’s wedding, helping lift the bride up high in a chair, twirling a little girl on the dance floor and drinking liberally: cocktails and wine, plus shot after shot of pálinka, a sort of Hungarian moonshine. Shortly after midnight, following a rooftop afterparty, Szabo set out on foot—the night was perfect for walking, still 80 degrees—and hailed a Lyft. He was staying at a Howard Johnson on 12th Street, but his ride missed his destination by 10 blocks. Around 12:40 a.m., Szabo, discombobulated, started stumbling toward the corner of 41st Avenue and 29th Street. Right across from Jones’s hotel.

“I’m not your Uber!” barked Hamidul Ghani, 24, who’d been out at a birthday party and was parking his car when Szabo attempted to open the rear passenger-side door. While Szabo banged his phone against the window, Ghani dialed 911. Only Szabo had wandered off, toward Andres Limonggi, who himself had just come home from work and now recognized someone who seemed lost. Limonggi did his best to help the stranger order another ride, but Szabo’s phone required a six-digit passcode and Szabo, incoherent and combative, proved capable of recalling only four numbers. He lurched toward another car, and Limonggi put a hand on his chest. Seemingly put off by this, Szabo punched Limonggi in the face, knocking off his glasses. Limonggi, a black belt in martial arts, put Szabo in a rear naked chokehold and swept his legs out from under him. Szabo lost consciousness for a few seconds, then woke up and began shouting, “I’m going to kill you!” Limonggi left in frustration.

It was about 20 minutes later that Jones turned right onto 29th Street, in search of a parking spot, and passed Szabo standing alone on a corner, attempting frustratedly to uproot a mailbox. On security footage Szabo can be seen wandering into traffic, hollering and gesturing at the X3, then wavering and balancing at a 45-degree angle. On another camera capturing the same moment, the coach stopped and reversed his SUV around a corner (against traffic on a one-way street) to park. Szabo approached. Then Jones’s brake lights obscured the scene momentarily from any recording. Down the street, Ghani heard a boom.

Jones darted out from his SUV, and Szabo retreated back to the mailbox, now desperate for refuge behind the immobile object. But Jones (who stands 6' 5") managed to easily flush out Szabo (5' 10") and strike him in the jaw, sending him backward, crashing his head against the sidewalk. Jones looked down, walked away, glanced back over his right shoulder once more and hurried off to the SUV. It was 1:42 a.m.

Altogether the interaction between theater-goer and intoxicated reveler lasted 39 seconds. Then Jones sped off with his fiancé while Ghani and Limonggi circled back and tended to Szabo, propping him up against a car to prevent him from choking on the blood spilling from his mouth, nose and ears. Ghani dialed 911 again and two EMTs arrived 12 minutes after the punch. Szabo was rushed by ambulance over the Queensborough Bridge to New York Presbyterian Hospital in Manhattan.

Jones would later explain that he circled the block, saw Szabo being tended to by others and drove the X3 to Long Island that night; he says Szabo had smashed in the rear window and he was afraid to street-park in Queens. But he returned to the Marriott the next morning to pack his bags for a flight home, and there, from his window, he looked down upon an incongruous scene. There was Pasteles Capy, a Mexican bakery known for tres leches cakes, with an awning that promises: ESTAMOS CONTIGO EN TUS MEJORES MOMENTOS!! (We are with you in your best moments!!) And out front he remembers seeing a white NYPD SUV, with yellow tape blocking off the corner where he’d left a bleeding stranger.

Police were seeking a “bald, dark-skinned male last seen wearing a light-colored long-sleeved shirt and jeans.” But Jones (who declined to comment for this story) was leaving that all behind. By Tuesday morning he was back in Winston-Salem, at the idyllic Old Town Club, for a $750-per-head charity golf event hosted by Chris Paul. Jones wore a white Wake Forest polo, khaki shorts and gray Nikes, and he paused to take a photo at one point with Paul, the former Demon Deacons point guard, who draped an arm across his shoulder.

At 2:52 p.m. Szabo was declared dead.

* * *

They were born three days apart.

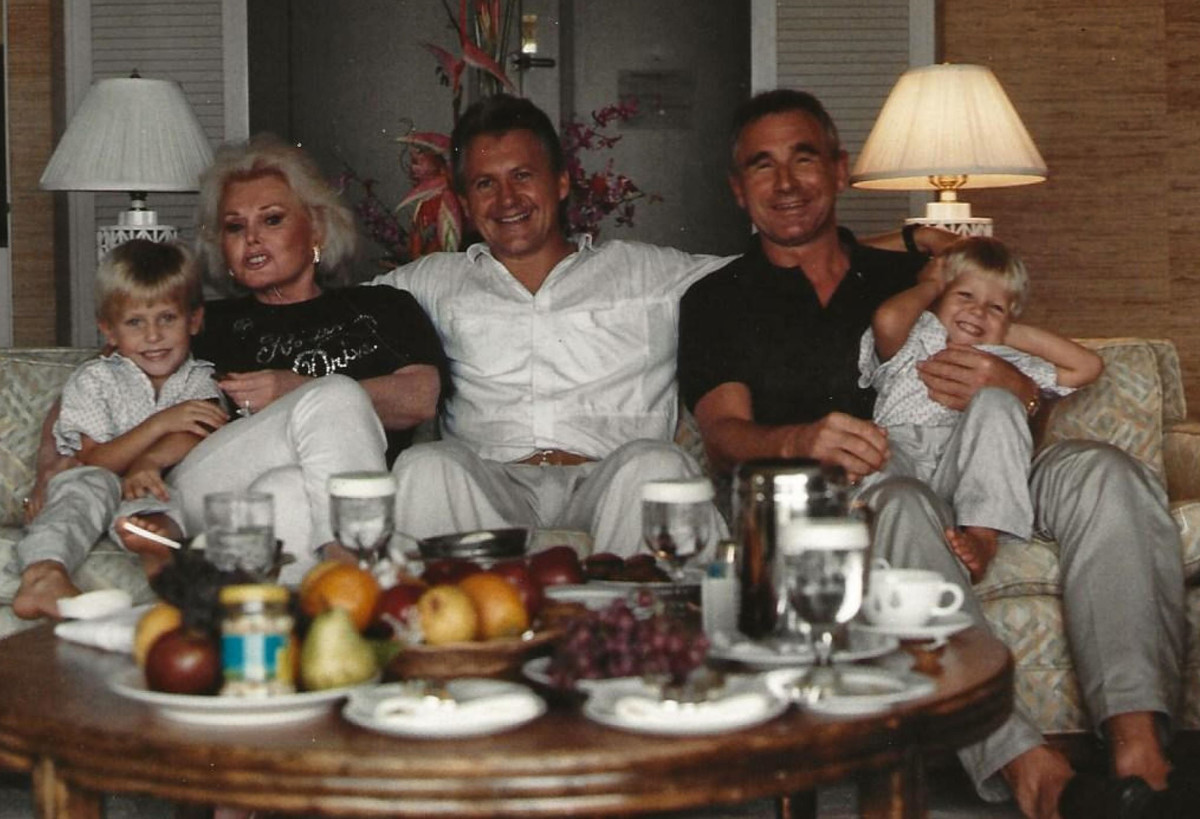

Szabo arrived first, on Nov. 26, 1982, in Kailua, Hawaii, on Oahu’s windward side. He was a towhead and a thrill seeker, inspired by his parents’ travels—to his mother Donna’s home in Montana, by Bear Tooth Pass; to see his father Balazs’s relatives in Budapest, including Sandor’s great-aunt, the actress Zsa Zsa Gabor. The family moved to the U.S. mainland when Sandor was seven, first to Connecticut and then to Raleigh, where the boy finished high school before going off to study at nearby DeVry.

Jones was born some 5,000 miles away, in Philadelphia. He would be raised in the shadow of an older cousin, Rodney White, who led UNC-Charlotte to the NCAA tournament in 2001 and played his way into an NBA lottery pick, No. 9 by the Pistons. Jones, meanwhile, struggled to garner interest from recruiters; he split his high school career between Maryland and North Carolina, then hopped around basketball’s backwaters, first at North Platte (Neb.) Community College and then at Division-II Arkansas Tech, where coach Mark Downey remembers him as a good teammate and a solid shooter—but “I wouldn’t call him the toughest player I ever had.” (In his online bio at future coaching jobs, Jones was heralded as “one of 50 players in North Platte’s … Athletics Hall of Fame.” A college spokesman says the school does not have such a hall of fame.)

Whatever it was that Jones lacked, his playing days ended in Arkansas. He took a job as a contractor with the Department of Homeland Security, working on revenue analysis, and kept his hoop dreams alive by moonlighting as a coach with Team Takeover, a traveling youth program on Nike's nonscholastic circuit. He worked with the likes of Victor Oladipo, a future NBA prospect, and earned the experience to slide in 2013 into an assistant job at Florida Gulf Coast, for a significant pay cut from his DHS gig. Such is the nomadic existence of a college climber: Jones went next to Virginia Commonwealth, for one year, then Central Florida, where he helped develop Tacko Fall, a 7' 5" center from Senegal, and reached the NIT semifinals. Then Wake Forest, where his greatest assets were his access to his old Takeover talent, his polished presentation—tailored suits, pocket squares, tie clips—and his direct approach. When Trevor Keels was a 14-year-old freshman at Paul VI High in Fairfax, Va., Jones offered the shooting guard a full scholarship to Wake Forest, after just his third career game. A father of two, Jones built professional relationships to last and believed no sale was ever really closed. His last stop before Hamilton was a surprise appearance at a barbecue on Long Island, where an incoming Demon Deacons freshman was being sent off by family.

Szabo, too, was what one coworker called “a breath of fresh air” amid a “sea of stale personalities” in his line of work. To his boss at What If? Media he was an innovator who had “a knack for creative solutions” as the company grew rapidly. And, like Jones, he had a certain flair. The same boss remembers one night, at dinner, Szabo eyed his superior’s fish entree and boasted, “You should come down to Florida. I will make you this [dish]—freshly caught and prepared. It will blow this away.”

Szabo was single and split his time between an oceanfront apartment he shared with his brother, Dominik, in Boca Raton, Fla., and the What If? office in Fort Lee, N.J. Outside of work he practiced yoga and led a busy life of recreational pursuits—skiing at Snowbird, in Utah; climbing Mount Batur, an active volcano, in Bali. Friends took note of the omnipresent backpack he wore and the confidence he carried in bulk. Upbeat and resourceful, he was persuasive and relished a good party, particularly if they were serving 42 Below, his favorite vodka. He was also, friends and family say, an old soul. He mingled with Boca Raton’s octogenarians, eating breakfast every Wednesday with a widower he’d befriended.

In August 2018, Szabo was in New York for a conference, and he skateboarded to work that week. His stepsister’s wedding happened to overlap with the trip, but without a date he’d waffled about attending. The room at the HoJo was a last-minute decision.

At the moment he crossed paths with Jones, his bags were packed in the hotel room, vacuum-sealed for the return trip to Boca Raton. Only Szabo’s toiletries were left out by the sink. His flight was scheduled to depart at 8 a.m. on Sunday.

* * *

Deep in the Queens County criminal courthouse, inside a windowless room below street level, a yellowing headline taped to one wall reminds the accused of their destination if they’re remanded: A HOLIDAY AT RIKERS.

Inside that room on Oct. 2, 2018, Judge Danielle Hartman turned to defense attorney Alain Massena and asked, “So, my first question is: Where is your client?”

Two days after Sandor Szabo died at the hospital, Jamill Jones flew back to Queens and turned himself in at the 108th Precinct, and Massena appeared with him at an arraignment. But now Jones was free on his own recognizance, and when case CR-027923-18QN was called, he was missing. Judge Hartman was upset. “I’m contemplating a warrant,” she said. “Now, where are we in terms of negotiation?”

Ultimately, Jones appeared at a second call, and he stood beside Massena as the judge noted his case appeared to be a possible felony, but that it remained a misdemeanor.

The main force working against Jones was not in court that day. Donna Kent, Szabo’s mother, had been pressing prosecutors from the beginning for a homicide charge. A petite blond who’d been a cheerleader in college, she displayed a fierce, uncompromising side in waging an aggressive campaign. She retained counsel, reviewed case law and fired off emails to the Queens District Attorney’s Office reading “URGENT-MURDER ... in YOUR District.” She considered her son’s death a homicide, and she bristled at the fact that Jones’s case was on the docket alongside traffic violations. “A slap in the face,” she said.

At the very least, she wanted him charged with criminally negligent homicide, which could send Jones to prison for as long as four years. And to make her point she met on several occasions with members of the DA’s office—but that relationship grew contentious as the DA resisted her efforts.

Eventually, that November, assistant DA John Ryan wrote to Kent’s attorney. Third-degree assault, a misdemeanor, he said, was the way to go. He laid out the mitigating factors: Szabo’s “extraordinarily high” blood alcohol content—0.39%, or five times the legal limit to drive. Jones’s claim that Szabo had “repeatedly, violently smashed” the X3’s rear window, seemingly instigating the situation. Plus there was a state statutory requirement that, to charge felony assault or manslaughter, the actor had to have intended to cause death or serious physical injury. The DA dismissed the idea that Jones had left Szabo to die on the sidewalk. In the end, Ryan wrote, “It serves no one’s purpose to overcharge.”

The way Kent saw it, her boy was being blamed for his own death. “He was drunk—so what?” she said. “He didn't deserve to die!” She visited the crime scene, holding up photos of her son, demanding JUSTICE FOR SANDOR. She petitioned state politicians to resuscitate a bill that would elevate one-punch homicides to felonies and worked to organize the families of victims to similar crimes. She wrote to Ryan and his prosecutor, Eric Rosenbaum, the lead on the case, with an email subject-lined JAMILL JONES IS A MURDERER, then told Rosenbaum not to sit with her during pretrial hearings.

Rosenbaum, ultimately, would leave the case, replaced by Kirk Sendlein, from the homicide bureau. The charge remained misdemeanor assault, and the DA would seek a year in prison if Jones was convicted. Jones, meanwhile, dropped Massena in favor of Christopher Renfroe, a regular in the Queens Boulevard courthouse. Jones insisted on his innocence through 13 pretrial hearings across 14 months.

Kent, too, remained unchanged. “Until I take my last breath,” she pledged one afternoon outside the courthouse, “I will never, ever forgive the man who took my son’s life. It’s not my responsibility. He can ask God.”

* * *

Jones wore a black hat and a purple VIP credential dangled from his neck one day last July inside Gym 3 at the Riverview Park Activities Center in North Augusta, S.C. Even up close, it was difficult to tell anything had changed.

The occasion was Peach Jam, the crown-jewel event of Nike’s Elite Youth Basketball League, a showcase for high school prospects. And Jones, who’d been an assistant with Team Takeover when it won the event in 2010, sat among 70-odd college coaches, a cellphone pressed to one ear, his legs extended on the court. He groomed his goatee with a pick, caught up with old colleagues and occasionally slipped into old form, shouting orders as Team Takeover played Mean Streets, from Chicago. “Pass the ball! … Move the ball!”

Mike Krzyzewski and Roy Williams sat a few chairs away, but for Jones the hard reality was: These were no longer his ACC counterparts. He’d been placed on leave shortly after his arrest, and he resigned after the 2019 Final Four. Jones called the subsequent days and months “an enormously painful time for all who have been touched by this tragedy.”

Keith Stevens knew Jones was “embarrassed.” Team Takeover’s coach is a power broker on the youth basketball circuit, and he took in Jones when he was 16, eventually helping him line up the Florida Gulf Coast job. Now he was urging Jones to hang around Team Takeover. He vowed to do whatever he could to line up another college job. “You can’t just hide,” he said. “You can’t stop living.”

Living, though, was complicated. A public arrest had derailed the career of a basketball lifer who seemed to have found his place in it all, a “tenacious recruiter,” says Virginia Commonwealth’s Will Wade, “who texts at all hours of the night—my type of guy.” Peach Jam was a reminder of all Jones had lost. Wade was there. As was Keels, the tenderfoot who Jones had years ago offered. Now he stood 6' 5", 210 pounds, with size-15 sneakers and a consistent stroke to complement his powerful drive. He was considering an offer from Virginia and drawing interest from Duke.

Jones was left to operate on the sidelines, everything in an unofficial capacity. But it was hard to tell in North Augusta. After one of Keels’s games, Jones jumped up and embraced Georgetown coach Patrick Ewing.

He returned to his chair. The sign above it read: COLLEGE COACHES ONLY.

* * *

A six-person jury had been selected for Jones’s trial, and opening statements had been made, when Sendlein expressed frustration in January about a key witness who seemed to have disappeared. Djenane Paul, the fiancé in the X3 with Jones—the person who best could have attested to any degree of threat Szabo might have conveyed and who could verify the damage to the X3’s rear window—had for weeks proved unreachable, he explained to the presiding judge, Joanne Watters. Fordham officials, Sendlein said, told him that Paul (a compliance officer who holds a law degree and whose sister is a New York City judge) hadn’t shown up for work recently. He’d attempted to serve her a subpoena at LaGuardia Airport, where she was supposed to arrive on a team flight, but she didn’t show. “Constant evasion,” he said. So the case went on without Paul. (Paul did not comment for this story.)

At trial, Sendlein allowed that Szabo’s behavior on the night of his death had been “not good in the least.” Then he called Ghani and Limonggi as witnesses to the punch and had Anne Laib, a pathologist in the chief medical examiner’s office, detail the physical carnage Jones had wreaked: the laceration below Szabo’s lower lip that required stitches; the two skull fractures; the bruising of his brain; the tears in the brain-stem nerve cells, consistent with a traumatic external injury caused by a sudden rotational injury to the brain. “That sort of injury,” Laib said, “can cause death.”

With each witness, Sendlein cued up two soundless video clips, caught by the closed-caption cameras at Pasteles Capy bakery. He highlighted the force Jones developed as he sprinted from the SUV, planted his left foot and threw a clenched right fist into the left side of Szabo’s jaw.

Throughout, Jones sat stoically at the defendant’s table, buoyed by few supporters: His mother came early in the trial, as did a couple of Team Takeover coaches. Eventually Jones took the stand himself, noting his newness in the court system—nothing but speeding tickets—and eventually testifying in his own defense.

In his telling, he was listening to music with Paul, the windows rolled up, and he did not notice Szabo as they first drove past him. Jones stopped the X3 and put it in reverse, he says, because he’d spotted a parking spot on a side street. Within seconds of reversing—at the point where Jones’s tail lights appear to have blinded security footage—he says he heard a boom and the rear windshield collapsed. (At trial, a work order for a window repair on the X3 was admitted into evidence.) Jones says he felt threatened and acted in self-defense. He remembers Paul crying, her face in her lap as he sprinted out of the SUV. “I put myself between her,” he says, “and what was coming next.”

Outside, he remembers yelling, “Yo!” and Szabo turning around, letting out “a loud chuckle, like He-he, ha-ha!” And then the punch.

On cross-examination, Sendlein questioned Jones’s decision-making. “You could have stopped and gone back to the car, right?”

Jones sat speechless for 10 seconds. Then: “I was in protect mode. ... I was afraid and I was thinking about the safety of myself and my fiancé.”

But the fiancé Jones says he was acting to protect never showed up in court. The couple shared a 203-minute phone call in the days after the punch; Paul’s cousin, a New York City police officer, advised Jones to turn himself in; the DA never managed to subpoena Paul; and by the time of the trial the wedding engagement had been broken off. (One week after Jones’s trial ended, after Paul could not be called to the stand, she was back at her Fordham job, sitting courtside for a basketball game against Davidson, high-fiving fans.)

In Sendlein’s closing argument, he painted Jones as having acted out of anger, not chivalry. He noted that Jones was trained in CPR but had failed to make any effort to assist Szabo. And on Feb. 6 the jury returned a verdict: guilty of third-degree assault. A misdemeanor. Jones, flanked by two court officers, shook his head.

Renfroe requested that his client not be remanded, and in the gallery Kent’s eyes widened, tears starting to fall. “No, no, no,” she said.

Judge Watters ordered Jones to report to probation prior to his sentencing, which is scheduled for June 16. When he's back in court, he faces as much as one year in prison.

After the verdict was announced, Kent hopped in an Uber to LaGuardia with her family. She was headed back to North Carolina.

* * *

Donna Kent is driving her dead son’s black Jeep Wrangler from a café back to her home in Raleigh. Inside, she traverses her living room, framed reminders of Sandor everywhere, and in her bedroom she removes a vacuum-sealed bag from beneath a bed. Inside are the clothes Szabo had packed in his Queens hotel. She opens the seal, breathes in his scent, then stops and quickly closes it. She fears too much is escaping. “I’m freaking out thinking about the day it stops smelling like him,” she says.

Kent used to fret over her son’s free-diving, too. He liked to gauge how long he could last underwater without oxygen, and he’d implore her to keep count as he held his breath and disappeared into the ocean or a pool. “Time me!” he’d shout.

“Sure, your lungs are great,” she’d say back, “but your brain’s shrinking.”

Those lungs—Sandor’s strongest organ, his mother thinks—were donated to a 73-year-old man in Massachusetts. Szabo’s right kidney and liver went to a 41-year-old woman; his left kidney and pancreas to a 44-year-old man. And his heart was transplanted to Sean Moynihan, a 59-year-old retired paramedic in New Jersey, who on Valentine’s Day 2019 drove 1,200 miles with his wife to Florida so he could meet Kent, thank her, and partake in a ceremony off North Miami Beach, where Sandor’s ashes were mixed with concrete to form an artificial reef.

“When it’s quiet, I can hear [his heart] beating strong and steady,” says Moynihan, who also attended every day of Jones’s trial.

Back home, Donna can hear the lub-dub of her deceased son’s heart, too. Sitting on her couch, she grabs a stuffed brown teddy bear that contains a recording of Sandor’s pulse. Moynihan had it made and gifted it to her when they first met. She listens to it regularly, but in her bedroom she fears it is fading.

“It was just working last night,” she says. “This is my little buddy at night.”

She squeezes the bear harder.

“How do I get it back?” she begs, her voice quivering. “I’m going to cry myself silly if the heartbeat goes away when the battery goes out.”