'We’re All Effed. There’s No Other Way to Look at This, Is There?'

Gene Corrigan's four decades in college sports seemingly ran the gamut of administrative experiences.

He was a coach and administrator during much of the Vietnam War, experiencing social unrest, campus demonstrations and counterculture movements. As an athletic director at the University of Virginia, he navigated the seismic changes brought on by the implementation of Title IX. He was the ACC commissioner during the conference’s game-changing expansion that added Florida State, and he was president of the NCAA in the mid-1990s while the association grappled with the first major wave of basketball players leaving early for the NBA.

“My dad had to deal with a lot of different things,” says NC State athletic director Boo Corrigan, “but he never had a pandemic.”

Across the country, administrators like Boo Corrigan are grappling with an unprecedented set of challenges—including the realization that life in college athletics may be, at best, temporarily and significantly altered. The impacts of the novel coronavirus to its cash cow, football, could bring a swift, and potentially permanent, end to the golden age of the industry. Just 143 days before its scheduled kickoff, the season’s existence is clouded with uncertainty as a plague hampers the nation, with billions of TV dollars and ticket revenues in jeopardy of disappearing.

Industry executives are already creating contingency plans for a nuclear fall of no football. At Clemson, for instance, Dan Radakovich has commissioned a handful of associates to investigate the what-ifs, calling it a disaster-preparedness committee. “I don’t know that we’ve named it,” he says, “because I don’t have an acronym for doom.”

For years, top-level programs have bathed in cash. They’ve erected lavish facilities, signed coaches to multimillion-dollar contracts and massively increased athletic staff sizes. Revenues have never been greater, giving is at an all-time high and, while attendance has shown a steady decline, premium seating and TV money are taking off. But the gravy train has hit a snag. If it leads to a major downturn in the college football economy, then what? “We’re all effed,” says one Power 5 athletic director who wished to remain anonymous. “There’s no other way to look at this, is there?”

A total or partial loss of the sport could send some athletic departments so deep into the red that one administrator predicted even Power 5 football programs shuttering. But the absence of football is only one piece. The long-term and severe financial impacts from an economic recession could not only reform forever how departments operate but also could spell sweeping changes to the landscape of college athletics—from the formation of a super division to a new wave of conference realignment, from money-saving travel modifications to football scheduling alterations, from discontinued sports to thousands of lost jobs.

Over the last two weeks, about two dozen school administrators and a host of industry experts spoke to Sports Illustrated to answer four pressing college sports questions amid the coronavirus pandemic: 1) When can on-campus practice begin? 2) What are the options for a football season? 3) How significant is football to athletic departments? 4) And how would athletic departments recover from a loss in football revenue? “The discussion that ADs are having about fall sports being canceled is a very real possibility,” says Ramogi Huma, the president of the National College Players Association. “It’s extremely hard to imagine any football in the fall on any level.”

When can on-campus practice begin?

Before football games, there must be football practice, and, before that, some say, there must be football training. If the first step to a return of football is virus-related—vaccine, etc.—the second step is multiple weeks of organized, on-campus activities (yes, we’re talkin' 'bout practice). At its highest level, college football has become a year-round endeavor. The season is followed by winter workouts in January and February, then spring practice in March and April.

In June, eight weeks of summer training—theoretically voluntary, but in reality mandatory—prepares players for camp in August. Then the season kicks off a month later. Rinse, repeat. The elaborate preseason training regimen of weight lifting, cardiovascular conditioning and seven-on-seven scrimmaging is considered necessary preparation for the physicality of the sport, the speed at which it is played and the intricacies of modern playbooks. So what’s the safest amount of preparation time a football team needs to play live games? This question produces a wide range of answers from those in the college athletics industry. Penn State athletic director Sandy Barbour’s suggestion of 60 days is on the high end, while South Carolina athletic director Ray Tanner’s pitch of one month is on the low end. Alabama coach Nick Saban suggests at least six weeks, and Clemson coach Dabo Swinney says players should return at some point in July to be ready for kickoff as it is currently scheduled.

The most qualified answer, though, comes from Tory Lindley, a senior associate athletic director at Northwestern and the president of the National Athletic Trainers' Association. “I cannot believe we can do it in a truncated time period of what we already do from a practice standpoint,” he says. “That right now is the month of August. It would be difficult to believe it could be shorter than it has been for decades.” When they do return to campus, athletes will have a half-dozen inquiries from medical personnel waiting for them. That may include a coronavirus test, physical exam, strength evaluation and a health history from their time in quarantine. “Where they’ve been, who they’ve been in contact with” says Lindley, “And we’ve got to go in depth as to what level you have executed the strength program you’ve been given.”

The academic and physical condition of players is a chief concern. While on campus, players get oversight from nutritionists on diet, strength coaches in the weight room and academic counselors in the classroom. Coaches fear the time away from that supervision will adversely impact less-driven players. “You’re telling me these kids have gone home and are eating like they’re eating with these nutritionists at the school? Come on,” says one coach.

Of course, a return to organized activities is contingent on various state gathering orders being lifted. While some hold an optimistic view of sports’ return this fall—including athletic directors, coaches and even the president of the United States—medical experts around the country are more cautious. Without advancements in coronavirus testing and vaccines, many believe organized athletic activities won’t happen. The former is much closer to being realized than the latter. The creation and mass circulation of a vaccine normally takes 12–18 months, doctors say. Former Food and Drug Administration commissioner Scott Gottlieb predicted that the U.S. economy will be 80% of itself until efforts at creating a vaccine are successful—and that will directly impact sports. “There are things that are not coming back,” Gottlieb said last week on CBS’s Face the Nation. “People are not going to crowd into conferences. They’re not going to crowd into arenas … and we need to accept that.”

A football team environment is a natural incubator for the spread of any illness. For years, viral infections have incapacitated entire squads. College football practices include more than 120 players and another 75 staff members. “In the absence of there being a vaccine, it would be difficult to know we have eliminated any threat to exposure with the virus unless they are tested,” Lindley says. The latest national models show newly diagnosed cases could taper out by the start of July. But predictive models are fluctuating on an almost daily basis and vary from state to state. Additionally, research has been fast-tracked on developing potential treatments and vaccinations, increasing hopes for a possible medical breakthrough that could drastically change the course.

Meanwhile, more schools each day are moving their summer classes exclusively online. At least 18 Power 5 programs have already made that announcement, including blue bloods Texas, LSU, Ohio State and Oklahoma. Can you have on-campus athletic activities—say, football workouts in July or early August—without having students in class? “If it's too dangerous for kids to be on campus, how would it be O.K. to play football?” says USC athletic director Mike Bohn. Not all agree. Tanner believes athletes could return before other students if it is deemed safe enough, and Texas A&M president Michael Young suggests that athletes could practice if there is teamwide virus testing. “Right now the tests take some periods of time to get back,” Young said. “If we could do that quicker, you could imagine getting the whole football team together, an (academic) class together, and test you all and see you are all O.K. and then you can all gather. That is conceivable.”

What are the options for a football season?

The unknown lurches over the sporting world. In college football, specifically, outlandish scenarios have been discussed, from moving the start of the season to July—which has since been debunked—to a 2021 schedule that begins in winter and ends in the spring. Playing games in the middle of the summer offends the sensibilities of those in the Deep South, while a January–February schedule would not play well in the Upper Midwest. Decision-makers who spoke to SI point to more practical options. Those include a truncated season, potentially with conference games only, that begins in October; a full season that starts in October, pushing bowl season to January and the playoff to February; and a season in which attendance is limited or altogether nonexistent. However, these are merely projections made months out. “What we’re dealing with is uncertainty,” Florida athletic director Scott Stricklin says. “It’s hard to know what decisions to make because so much is up in the air. You try to do the contingency thing best you can, but there are a lot of unknowns.”

That said, football is such a financial force for athletic departments and universities that one Group of Five athletic director says, “If they have to start football in a blizzard in January, they’re going to do it.” Contingency models are just now being weighed internally among administrators, with most discussions long on theory and short on specificity.

At Oklahoma, athletic director Joe Castiglione and staff are investigating the topic on a school level. “We’re doing all sorts of modeling on what the football season may look like, from a delayed start to no fans to pushing the entire season into the winter or spring,” he says. “We could end up throwing it all away, and that would be great, but we can’t afford to wait until the last minute to think about it. We’re trying to think of any way to keep the season alive, because of the economic engine it is for so many other sports. This year, it could be an economic engine on steroids.”

Despite the fluidity of the situation, schools are somewhat on a timetable. Last week, Pac-12 commissioner Larry Scott said that a decision on football season and the postseason would need to be made by the end of May. After all, a truncated season starting later than scheduled could make for scheduling chaos that needs weeks to resolve. Even if football returns, most feel that it won’t be the same cash cow. Will fans even be allowed to attend? If they are allowed, will they attend? “What’s the psyche of people to get back into close quarters in these stadiums after two months of this social distancing and worried about recurrence?” asks one SEC athletic director.

Ross Bjork, A&M’s athletic director, says the start of football comes down to the government. Most states are currently under a stay-at-home order, restricting large gatherings. These orders are independent of one another and are expected to eventually be lifted at different times. Infections and deaths vary widely from state to state. For instance, the city of New Orleans alone has 10 times the number of cases as all of Nebraska. “What if Texas is farther along than Colorado and Colorado says, ‘We can’t play yet,’ but Texas is in good shape?” Bjork says. “We play Fresno in a non-conference game. What about California?”

If the virus does subside, medical experts have warned of a second wave arriving during the fall. For some, the concern runs beyond football. “What about basketball?” Bjork asks. “When are they up and running? You start looking at winter. You’re talking about multiple layers.”

How are athletic budgets impacted by football?

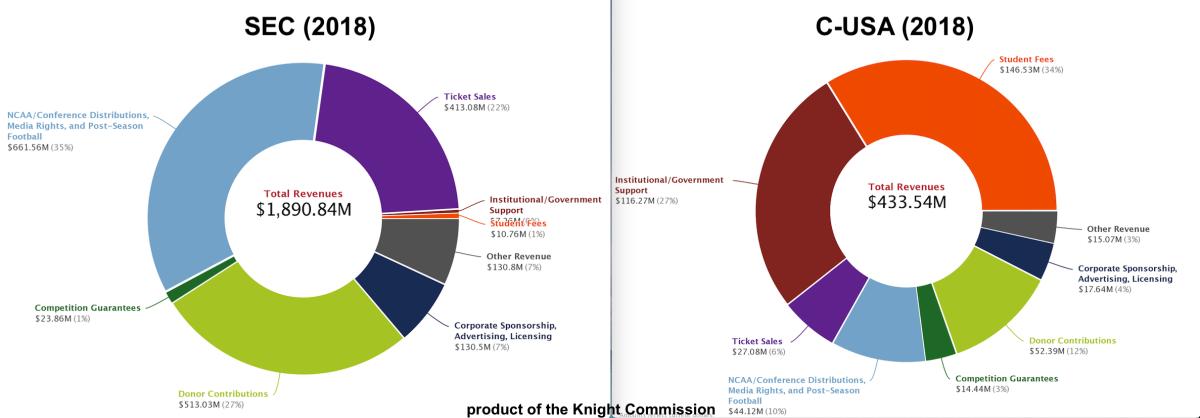

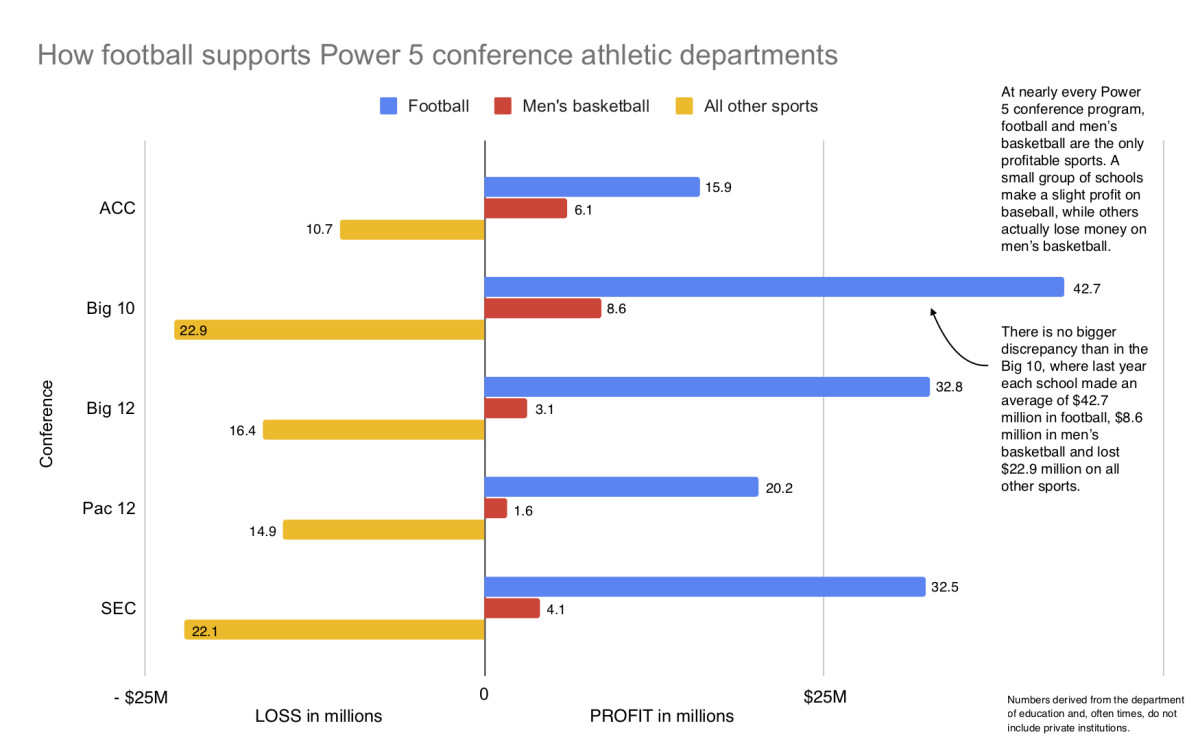

At LSU, Scott Woodward presides over an athletic department sponsoring 21 sports. Eighteen of them lose money. And he’s one of the lucky ones. At most universities, two or fewer teams turn a profit: football and men’s basketball. LSU is in the minority, as its baseball program is normally in the black, too. Financial documents for the 2016–17 LSU athletic cycle paint a stunning picture of a school’s reliance on football. That year, the Tigers’ football program turned a profit of $56 million, men’s basketball made $1.6 million and baseball brought in about $570,000. The other 18 sports lost a combined $24.2 million. “Football is 85% of our revenue,” Woodward says. “That says it all. It is the engine that drives the train.”

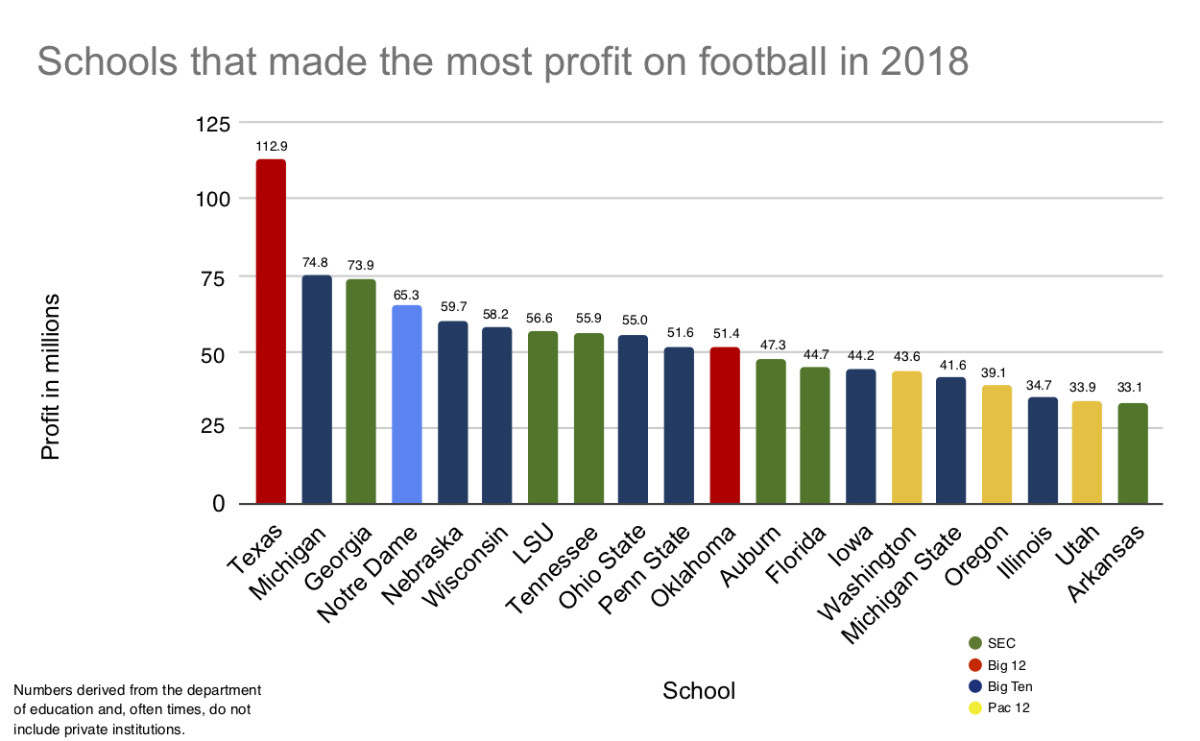

This isn’t exclusive to LSU. In fact, Power 5 public universities made an average of $28.2 million in profit last year on football, according to self-reported financial documents SI examined. The discrepancy between football and all other sports is severe across the country. Even in the basketball-crazed ACC, football outperforms hoops. The average ACC football program made $15.9 million, while the average basketball school pulled in $6.1 million. Among the 65 Power 5s and Notre Dame, just four schools had a men’s basketball team make more than its football team: Syracuse, Duke, Kentucky and Louisville.

“Football allows us to have these other sports. It’s a big amount,” Radakovich says. “All the folks working in college athletics understand what a big economic engine it is. You look at big revenue drivers—ticket sales, donations, conference distribution—those are all linked together, and the centerpiece is football.”

The numbers are mind-boggling. Texas led all schools last year with a profit of $112 million in football. SEC schools in 2018 pulled in an average of $40 million each in contributions, most of them tied to football. The Big Ten distributed more than $700 million to its schools last year, including a football-bolstered TV contract and football-buoyed postseason revenues (bowl games, College Football Playoff, etc.). “I’m nervous,” Texas AD Chris Del Conte says. “We have nine different models, all the way from A to Z. We’re running an enterprise based on the discretionary income of people. We’re fortunate to have a very passionate fan base, but when you look at what’s happening in our country, we need that to dissipate first.”

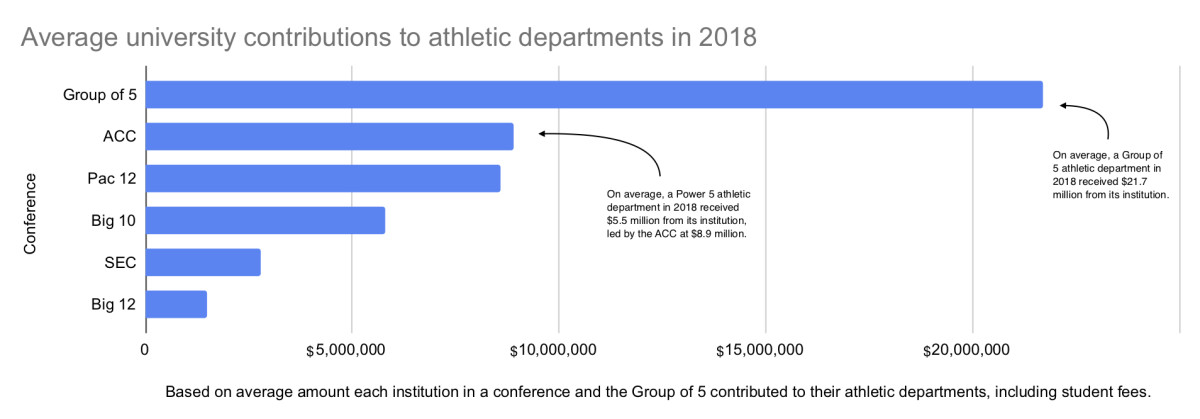

While Power 5 programs heavily lean on football revenues, those in smaller divisions, the Group of Five, are reliant on state and institution support. In fact, the average G5 school got $21.7 million in athletic aid last year from its university, while that number among Power 5 schools was $5.5 million. In many cases, school funding is responsible for more than half of a Group of Five’s athletic budget. Even the richest G5 schools, like Houston, UCF and Cincinnati, got at least $28 million last year from their schools. “So many Group of Fives depend on enrollment. If that reduces, it’s a hit,” says Eddie Nuñez, the New Mexico athletic director. “It’s a hit for this [fiscal] year and next year.”

Enrollment numbers aren’t the only worry. Many G5 athletic directors are anticipating cuts to higher education. UCF athletics received $28.8 million from the school and state last year. With Florida tourism shut down because of virus-related closures, athletic director Danny White is concerned. “The state’s ability to support the university system could have a trickle-down effect on our department,” he says. “We were planning on investing in building budgets for next year. Increase in game operations, staff sizes. We’ll likely take a pause on that.”

At Houston, Chris Pezman is taking a blow from the cancellation of special events he expected to host at on-campus venues. Combined with the NCAA tournament distribution loss, he may be out upward of $3 million, or 5% of his budget for fiscal year 2020, which runs through June at most places. “Everybody is worried about the fall. If this gets into the fall, football will be so secondary to what’s going on globally in the economy,” Pezman says. “It’s going to decimate you.”

Meanwhile, at the highest level of the sport, officials are bracing for a loss in all three major revenue-producing categories: conference distribution, ticket sales and donations. Conference/postseason distribution and TV money is a significant part of every athletic budget, as much as 40% in the Big Ten. It includes postseason football and megamillion-dollar TV contracts that could be impacted without a season or in the case of a truncated season. “The revenue from ticket sales and concessions, that’s all significant, but we could figure that out. Your expenses get reduced,” Young says. “On the other hand, where the revenue comes from athletics is really the TV contract and distribution. That’s really important.”

Young and the Aggies have something else to worry about, too: donations. The economy is hammering businesses, including those operated by big-money boosters. For A&M, tucked in the heart of big oil and gas country, that’s especially significant. At most Power 5 programs, donations are usually responsible for about 25% of revenue. At A&M, it’s more than 40%. The Aggies got more than $90 million from donors last year, much of it from oil tycoons.

A month into virus-related shutdowns, some schools are already seeing a drop-off. One Pac-12 school, for instance, was expecting upward of $20 million in contributions as part of this fiscal year. It’s no longer coming. “If you can salvage the TV money [and play without fans], can you go to your donors and say, ‘This is an extraordinary time, can you stay with us through this?’” one AD asks. “Then you try to reward them later. The problem is, I don’t know when you catch up on that.”

How do they plan to combat potential budget shortfalls?

Schools and organizations have already started down money-saving paths. Athletic directors and other high-ranking department leaders are taking pay cuts at places like Iowa State and Wyoming. In the Pac-12, Scott is slashing his pay 20%, and the executive staff is cutting 10% from its salaries. The Pac-12 Network laid off 8% of its workforce, and NCAA leaders announced a 20% cut in pay.

Across the country, athletic leaders are meeting to create penny-pinching contingency plans for fiscal year 2021. Dozens of schools have extended their football season-ticket renewal deadlines, giving boosters more time during this period of economic uncertainty, and many school administrators are getting creative with payment plans.

Athletic directors view scheduling and travel as key money-saving areas. One Group of Five athletic director suggests trimming Olympic sports’ competitions, and another says multi-team, neutral-site round-robin events could pop up for non-revenue sports. Even football scheduling might see some long-term effects in two ways: 1) fewer games against Group of Five programs, as to avoid guarantees stretching into the millions; and 2) fewer long road trips for non-conference games to avoid travel costs. The average price to fly a football team in a charter plane is roughly $120,000, administrators say.

At UCF, White even suggests that the federal or state government lend support to help his department balance the 2021 budget. His only other option, he says, might be to take out a long-term loan. “As I sit right now,” he says, “I don’t see a feasible option.”

The skeptic might ask why, after years of swimming in a surplus, did Power 5 schools not save cash? Some do have reserves, often buried within their privately run fundraising arms. But many operate with a goal of breaking even, pressured from the outside to “look poor,” says Andy Schwarz, an antitrust economist and cofounder of the Professional Collegiate League, an upstart he expects to rival NCAA basketball. “Broadly speaking, these guys aren’t allowed to carry over money here or there. There are exceptions, but most blow all of their money every year. They can say, ‘Look, we don’t have any money! We can’t pay the athletes!’ ”

There is another way to save money: cutting sports. “If football and basketball decline, you could see a number of schools scale back athletic programs all together,” says Young, the A&M school president. “Schools that offer 25 sports, you’ll see some schools begin to put hiatus if not stop the sports that are expensive and not revenue-generating.” In the 2018 reporting year, sports not named football and men’s basketball cost Power 5 athletic departments more than $960 million, or $17 million a school. No program lost as much as Michigan and Ohio State, at $39.9 and $38.8 million respectively. As two rich blue bloods, the Big Ten powers bring in enough football revenue—a combined $125 million in profit—to pay such a stiff price tag for all other sports. Not everyone, especially those in the Group of Five, are in similar positions.

Eliminating sports is a time-consuming and pain-staking endeavor that can lead to backlash from athletes and alums connected to those programs. The decision includes maneuvering around Title IX and making sure you’re not getting rid of a sport that actually brings tuition dollars into the university. The vast majority of non-revenue sports dole out only partial scholarships, leaving the player to front the rest of their school fees. There’s the NCAA requirement to worry about, too. The governing body requires Division I schools to sponsor a minimum of 14 sports.

A&M’s Bjork, a man presiding over one of the richest departments in the country, says the virus will have long-term effects on college sports spending. “Perhaps it’s travel. No one will cut back on what we do for student athletes, but how we get to certain places—hotels we stay in, meals, staff sizes,” he says. “They're all going to be on the table. We’ve got to look at it.” Some suggest the potential budget shortfalls this year will curtail exorbitant salaries and lavish facilities—for good. “The facilities boom is going away,” says one AD. Said a former college coach: “I think this just changed the game on super salaries.”

Meanwhile, many college administrators are in lonely offices—or quarantined in their busy homes—trying to answer a two-part question: Will we have football, and if not, how will we survive? “If we don’t play football, it means campuses are closed. It rolls up to a much bigger circumstance,” Radakovich says. “That’s the place sports finds itself right now: We are a part of a much bigger issue in our country.”

More From SI.com Team Sites:

Nick Saban: 'It's Important For Us to Keep the Kids Engaged'

Ohio State Precautions Stretch Close to Football's Start

Will Muschamp: 'We Have to Prepare as If We’re Playing This Fall'