Spring Practice Disparity Creates an Unusual Challenge for College Football Teams

National signing day used to be the busiest day in college football every year. Thousands of high school seniors signed binding letters to attend and play for a particular school. Fax machines buzzed. Phones rang. Celebrations raged. Lately, with the addition of the December signing period, the traditional February signing day has lost much of its appeal.

But at Coastal Carolina, this year’s signing day, Feb. 5, was just as busy as ever. That’s the day the Chanticleers kicked off spring football practice, a whole three weeks after the 2019 college football season ended with LSU’s win over Clemson in New Orleans. At the time, beginning spring practice so early—roughly a month before the average start date—seemed peculiar, if not downright silly. And now? “This year, we look like we’re Nostradamus,” laughs Jamey Chadwell, Coastal Carolina’s second-year head coach.

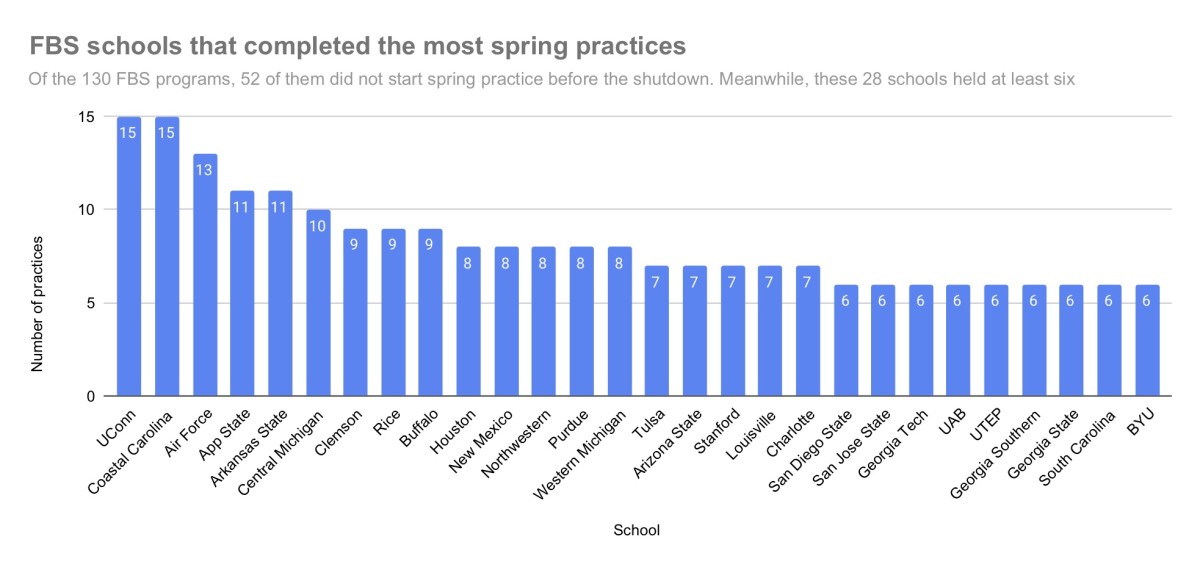

The Chanticleers are one of two programs in major college football to have completed their entire 15-session spring practice before the virus pandemic shut down sports. The other: UConn. Huskies coach Randy Edsall started his spring practice two days before signing day. Both teams wrapped up practice a week before the coronavirus froze the sporting world, suspending and then eventually canceling all spring football workouts across the nation.

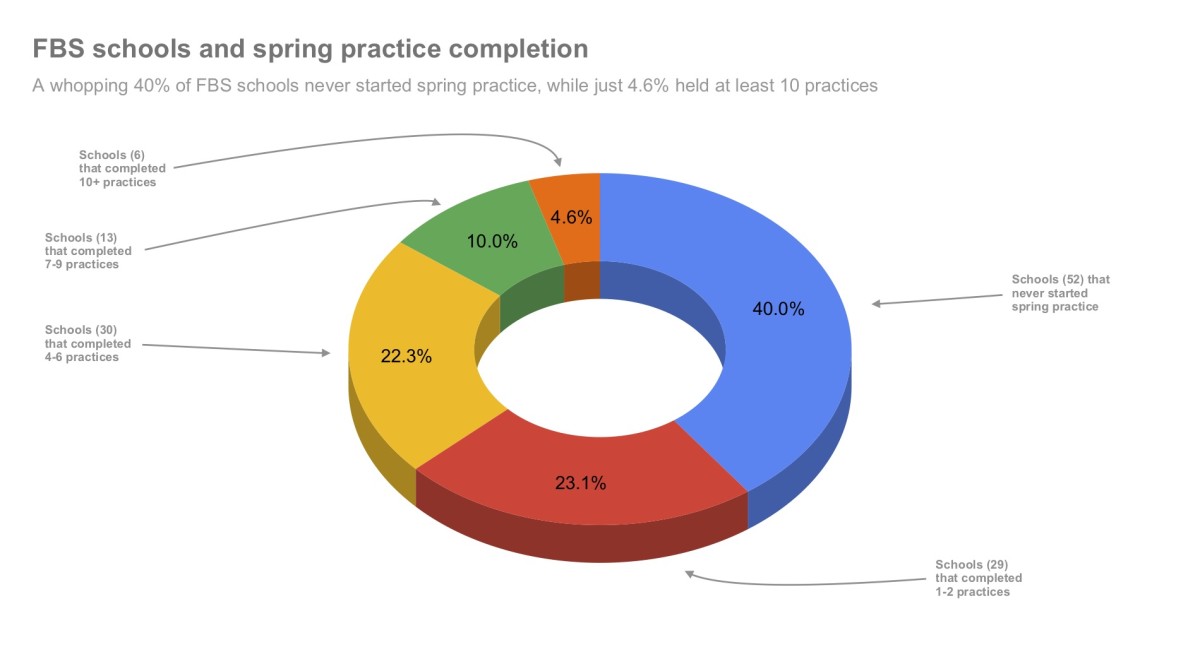

While UConn and Coastal Carolina finished their springs, more than two-fifths of the FBS (52 teams) didn’t even start theirs. Of the 130 teams, a whopping 111 of them didn’t reach the halfway point in their allotted 14 spring practices (excluding a 15th—the spring game). Eight schools each in both the Big Ten and SEC never got to Day 1. In fact, if your team completed four or more practices, it was ahead of the nationwide average of three.

The playing field isn’t quite even. Bluebloods like Clemson and Stanford got in nine and seven practices, respectively, while Alabama and Texas got zero. Entire states never kicked off spring. In Mississippi, Ole Miss, Mississippi State and Southern Miss didn’t have a single day of practice. In Florida, a state with seven FBS schools, just 12 days of spring practice were had. In the football hungry state of Alabama, the only FBS team to have at least one spring practice was UAB. It had six.

Many teams were a day or two away from starting before campus shutdowns began March 11 and dominoed through March 14. Both Florida and Michigan State were scheduled to start practice during that stretch. The Crimson Tide, meanwhile, were an hour from taking the field before suspending their first practice. In a normal year in FBS, teams would have completed a combined 1,950 spring practices. This year, they finished with 395. There will be no rainchecks. “You can’t make up for a loss of spring practice days or things like that,” says Jon Steinbrecher, the MAC commissioner and vice chair of the all-powerful NCAA Division I Council. “You don’t even try to make up spring. We’re past that discussion. The focus is on can we get the season going.”

While there are more pressing issues aside from spring ball, its absence will be felt and seen, some coaches say. Coaches normally use spring as a time to install new schemes, gain insight on starting competitions, build solid depth and evaluate young players, specifically freshmen who enrolled in January. UConn and Coastal Carolina combined to have 21 rookies join at the mid-year. They all participated in 15 spring practices. “It’s a distinct advantage in my opinion. I’d go as far to say it’s a competitive advantage,” says West Virginia coach Neal Brown. “We can’t make up those reps. That is the biggest loss in all of this from a spring ball perspective: missing repetitions. Those teams have a competitive edge over the ones that didn’t.”

A good thing for Brown: the Mountaineers were one of six Big 12 teams to hold zero spring drills. The disparity in many leagues is much greater. For instance, in the ACC, three teams never started spring while three others had at least six practices each. In the Big Ten, Northwestern and Purdue each completed eight practices while the rest of the conference combined for 12. In the Pac-12, the only three teams not to have started spring were the three that may need it most. Colorado, Washington and Washington State have new coaches. “For a new staff, it’s a tremendous disadvantage not to have spring,” says Edsall. “You’re trying to implement new systems. You can do things on Zoom and those things, but getting guys out there and doing it, you miss out on that. If you lost a lot of guys and had young guys and needed extra reps, it hurts you too, but in the long run, people will find a way to deal with it.”

First-year Baylor coach Dave Aranda is already doing just that. The Bears had zero spring practices, so his focus in the early portion of the 2020 season will be on fundamentals and technique more than scheme and strategy. He’ll use basic concepts and hope his players can win individual battles. He has a glass-half-full approach to this. In the past, at his stops as defensive coordinator at LSU and Wisconsin, spring practice has given him false impressions of his units. “I’d think we’re going to be a blitz-heavy group or a two-gap that just pounds people,” Aranda says. “And the season would arrive or camp and almost 100% of the time, that would be wrong.”

He admits, though, that losing reps is significant. The repetitions are videoed, stored and used by coaches and players over the course of the spring and summer, studying technique, movements, etc. Fifty-two teams have zero spring practice clips to watch. Two teams have a combined 30 clips. “It’s huge. It’s seriously misunderstood,” Chadwell says. “We’re all visual learners. Everything is visual. For us to have position meetings and say ‘This is our install. Let’s go back at it and see how you executed in the spring,’ because maybe they didn’t play in the fall.”

To even the playing field, some coaches hoped to get OTA-type summer workouts for every spring day lost whenever campuses do open. Those hopes are dashed. “The reality is it’s going to be really hard to create balance on this,” says Todd Berry, executive director of the American Football Coaches Association. “Believe me, we’ve modeled it, the AFCA and NCAA. We kicked the can pretty far down the road. It was difficult to come up with a really equitable and fair model.”

While limited or no spring ball might be toughest on new staffs, those teams with new quarterbacks have it hard, too, especially if the QB has never thrown a pass in a college game. Alabama’s highly touted freshman quarterback, Bryce Young, enrolled in January and was poised to compete for the starting job during spring. He’ll now have to wait until August. Those staffs overhauling one side of the ball or the other may find it tough, too. Take Syracuse. The Orange are shifting from a 4-3 to a 3-3-5 defense, a transition expected to happen over spring practice. Syracuse got all of three days of drills. At Texas, coach Tom Herman has both a new offensive and defensive coordinator. The Longhorns didn’t hold a single practice.

At Arizona State, Herm Edwards got seven practices, the second-most of any Power 5 team, but he says spring ball is somewhat overblown. “Even the practices we had, it ain’t going to matter,” Edwards says. “By the time you come back, you missed three to four months, and you’re starting over. Coaches are always about practice, always on this practice deal. I get it, but in the end, what coaches want the most is we all have the same amount of time.”

This year, they won’t get it. Some will face a disadvantage in the spring as well as the summer. Because states will reopen at different times, schools will be on different timelines on a return to campus for pre-camp training. “Does the NCAA mandate when everybody can come back and start?” asks Chadwell. “Our state of South Carolina, we’re going to open up some soon. Does that allow our teams, Clemson or South Carolina, to bring back our players in June? That’s going to be an interesting piece.”

No one really knows that answer, including conference commissioners who spoke this week with Sports Illustrated. At some point, an NCAA governing board and/or a conference board will determine a date to return to training, but state-wide gathering orders might prevent some programs from returning to campus. What then? Who knows. Edsall says he’s leaving those decisions to medical professionals. “I understand football and understand what’s good for football,” Edsall says. “I’m not a medical doctor and infectious disease doctor. Let’s let these people, the experts … let’s lean on them.”

Edsall is sure of one thing, at least: He’s got 15 spring practice videos that he can watch in his spare time while he and his family are quarantined in their Florida vacation home. This was the second straight year Edsall kicked off spring practice at such an early date. His reasoning: avoid practice being interrupted by spring break. Chadwell shared that sentiment, but there are other perks, too. Players injured in spring are afforded a longer time to recover. Unbothered with football, players can focus on academics during the critical month of April, which normally ends with final exams. “Just taking a look at the whole calendar and how it’s changed, I said, ‘This seems more logical to me,’” Edsall says.

But what about the weather in February in Connecticut? The Mark R. Shenkman Training Facility provides cover from the elements. In fact, without it, UConn would have never reached practice No. 15 before the shutdown. “Before we had that facility, we never started before spring break,” Edsall says. “One year we had to shovel snow off the outdoor turf field to practice in late March and early April.”

Check out SI's full list of spring practices for the 130 FBS teams

More From SI.com Team Sites:

Answers and Unknowns: Moving on From Clemson's Spring

Latest NCAA Ruling Opens Door to More Lawsuits

Five Things Purdue Will Miss Out on With Limited Spring Workouts