Exploring the Ramifications of No College Football on the Players

In his decade as a college sports psychologist, Brandon Harris never has seen a more anxious time among athletes.

In a COVID-19 world, the unknowns on a college campus are extensive. “There’s a lot of anxiety about what we call the ‘What Ifs,’” says Harris, the coordinator of Georgia Southern’s sport and exercise psychology program. Players, usually focused on a season opener right now, are submerged in questions.

What if I test positive for COVID-19?

How many players around me are sick?

Is my family back home OK?

Will there be a fall season?

For some, the answer to the last one already has been answered. For others, including those at Georgia Southern, it remains unanswered just two weeks before the season’s first game.

While Harris and his medical team are helping kids through these anxious and uncertain times, they simultaneously are preparing for something far worse. “You have athletes and they’ll tell you, ‘I don’t know what I’m going to do if we don’t have a season,’” says Brandy Clouse, a longtime college football athletic trainer who’s now a senior associate athletic director at GSU. “When you don’t have a season... so much of their identity is tied up in their sport.”

The ramifications of playing a collision-filled sport amid a pandemic have been explored extensively. There’s fear that athletes will contribute to both community spread and resource shortages, potentially infecting the vulnerable while also using testing supplies for non-essential activities. There are the unknowns associated with the virus’ impact on the heart, and there are the predicted in-season interruptions as portions of teams get quarantined or isolated.

But for the most part, the consequences of not playing a season—aside from the well-reported financial strains—have gone somewhat overshadowed, buried beneath the serious nature of the aforementioned viral-related issues. This has frustrated many in the college football world. The other side should be told.

Several coaches, sports psychologists and administrators spoke to SI about the ramifications to players without a season. From mental health issues to emotional breakdowns, they detail the pitfalls of a football-less fall for athletes whose lives revolve around the game. One coach says he “loses sleep” over the consequences. Support staff members are bracing for athletes to experience bouts of depression and distress, which, they say, can lead to drug and alcohol abuse—or worse.

According to a recent study released by the CDC, one in four people aged 18-24 have considered suicide during the pandemic, significantly higher (10%) than other age groups.

“When we identify around one aspect of who we are, it can be really unsettling to have it be taken away from us,” says Sian Beilock, a sports psychologist and cognitive scientist who is president of Barnard College in Manhattan. “These players put their whole life towards this. They really struggle now with how they’re going to see themselves.”

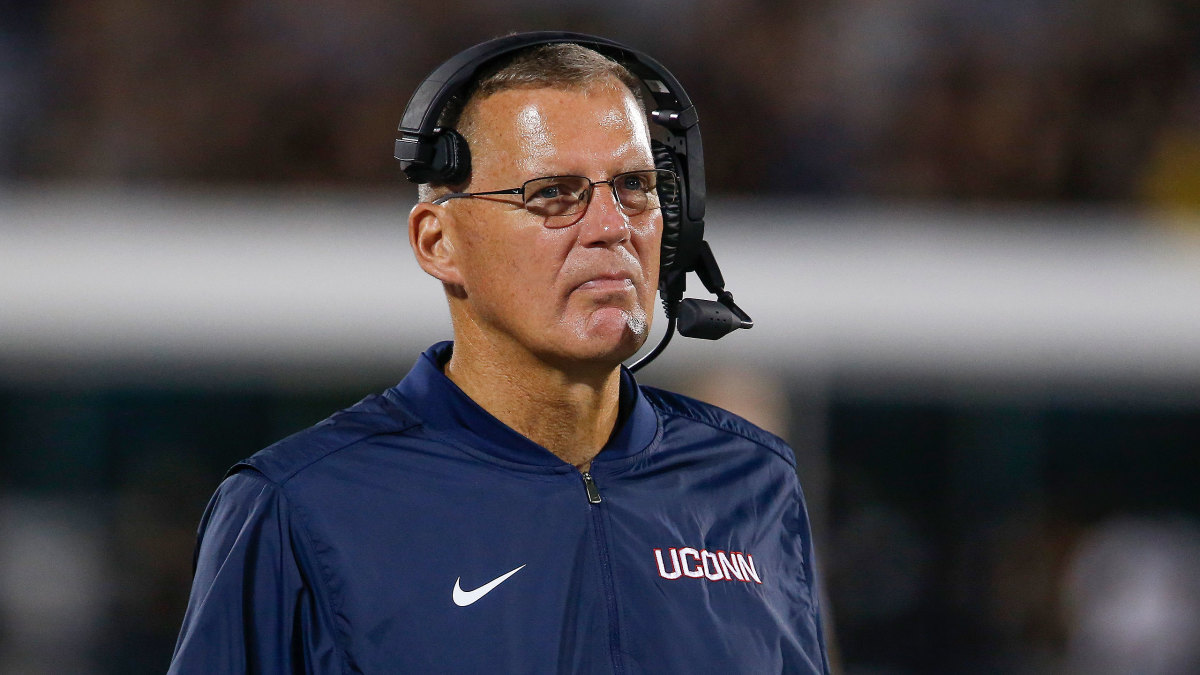

But not everyone agrees with the narrative that repercussions without football outweigh playing the sport during a pandemic. Even one coach, UConn’s Randy Edsall, described the narrative as a “cop out” used by those in college athletics whose underlying reasons for playing this fall are green in color.

“If there wasn’t so much money involved in the schools, we wouldn’t be having this discussion. The reason we’re trying to play is the money,” says Edsall, whose Huskies were the first FBS program to independently cancel a fall season. “There are going to be a lot harder things for players in life than not playing football. This is a game that we’re playing. It’s not life or death.”

Just because UConn is not playing a season doesn’t mean the team won’t remain together this fall for workouts, meetings and light practices. Just this week, the NCAA approved a proposal to grant teams not playing in the fall 12 hours of football activities per week, including five hours of on-field contactless work.

The ruling torpedoes an oft-used notion that schools deciding against playing a season would shoo their players from facilities this fall. That’s not the case. In fact, Edsall says the downtime can be useful, especially for players who have fallen behind academically.

Part of the NCAA’s decision in passing the 12-hour rule is rooted in concerns over the athletes’ situation, suggests Todd Berry, executive director of the American Football Coaches Association who sits on the committee that recommended the new policy. “We hope this keeps them connected and mentally healthy,” he says.

Even some of the smallest FBS programs provide millions of dollars in care to their athletes. From lavish meals to elite medical support, players are encased in somewhat of a protective bubble that also includes weekly testing. But the most significant benefit schools provide is the enforcement of safety protocols, says Gerry DiNardo, an analyst on the Big Ten Network and former major college head coach.

“One of the things bothering me is coaches saying (players) are safer with us than when they aren’t with us,” DiNardo says. “What they mean—and they should say what they mean—is when they’re with us, we control their actions. When they’re not with us, they can go to someone’s apartment, not wear masks.

“It’s ‘They’re safer than if they leave us and then don’t buy into how to stop the pandemic and spread it more.’ And that’s true.”

With many coaches, there is another sticking point. In a football-less fall situation, the motivation—games—is removed. Coaches question how focused their athletes will be in workouts without a game to play or on academics without a reason to qualify. Many of them use the carrot-for-the-horse analogy. Without the carrot, what’s driving that player to achieve both on and off the field?

If the season is eventually canceled, Neal Brown, head coach at West Virginia, says his “biggest worry” is his athletes’ mental health. Every FBS school, even some on the Power 5 level, does not employ a team of sport psychologists. Some football teams share one or two such staff members with other squads on campus. Other schools use student interns in those roles.

“I understand COVID is a novel virus. It’s new. We don’t know the longer term ramifications. It’s serious, and I don’t want to make light of it,” Brown says, “but what's not getting talked about enough is the collateral damage.”

LaKeitha Poole is starting her fifth season as LSU’s director of student-athlete mental health. Her concerns, if there is no season, range from the good (a focus on academics and forming new hobbies) to the bad (emotional issues such as anger and frustration). Poole has been around enough athletes to know that sports bring structure to their lives. It’s a built-in part of their “psyche,” she says.

Harris says he’s concerned about depression, which may result in athletes developing unhealthy coping mechanisms. “I don’t know how much we’d see the likely increase of alcohol but it’s something we pay attention to,” he says. The medical staff at Georgia Southern met last week to explore contingency plans and mental health preparedness for no season.

It’s a real issue for coaches and administrators alike.

“I lose sleep about it,” says Will Healy, the 35-year-old head coach at Charlotte. “What they’ve been through in the last five months is probably some of the most adversity they’ve been through in their lives. Now throw in the possibility of canceling a season on top of all that. Their identity is football. It’s the only thing they feel like they can have. But the blessing is that we get a chance to help them create an identity outside of the game of football.”

Those coaches in conferences that have already canceled their fall seasons are turning their attention to life outside of the game. For instance, at Toledo, coach Jason Candle plans this fall for his players to take part in more community outreach in the city. He wants them to be present and visible. He looks at the downtime this fall as a positive. He can begin to help athletes prepare for life after football.

“We talk all the time about being resilient and handling diversity,” says Candle, who recovered from an asymptomatic experience with COVID-19 earlier this summer. “The reality of this is football is going to be taken from you and me and everybody. In most cases, it’s taken from them before they’re ready for it to be taken. This is a preview of what life is like after college.”

At USC, coach Clay Helton has time now to focus on mental and physical improvement with his players: building both character and speed. The Trojans will spend the first two weeks of September holding what Helton describes as a “speed camp” before finishing the month with an NFL combine-like event. “It gives us an opportunity to develop kids in a different way and have fun,” Helton says.

Eddie Kennison, a former NFL receiver who now serves on the support staff at LSU, brings up a different angle: What about the upperclassmen who need to prove themselves to the NFL? Like, for instance, quarterback Joe Burrow, who in one season last year went from a sixth-round projection to the No. 1 pick in the draft and the Heisman Trophy winner.

LSU is stacked with players in a similar position. With a good year, they could vault up draft boards. Sure, they could use the NCAA’s extra year of eligibility by returning next year, but that’s not always an easy decision to make. Some have families to support. Others have spent years working up to 2020 as their final season.

“It’s a scary scenario for them—the uncertainty,” says Kennison. “We’re moving forward trying to play, so it gives them some hope. If I were in their shoes, I’d be concerned. Am I going to play and am I going to get seen?’”

Meanwhile, back at Georgia Southern, Harris is preparing for the worst-case scenario: no football.

“It’s not uncommon to see depression and anxiety simultaneously,” he says. “It is important that a mental health official or coach communicates with them a message: It’s OK not to be OK. The last thing we want to do is tell them it’s not OK.”