'It’s Devastating:' The Stark Reality of a Fall Without Football Hits Home in Champaign

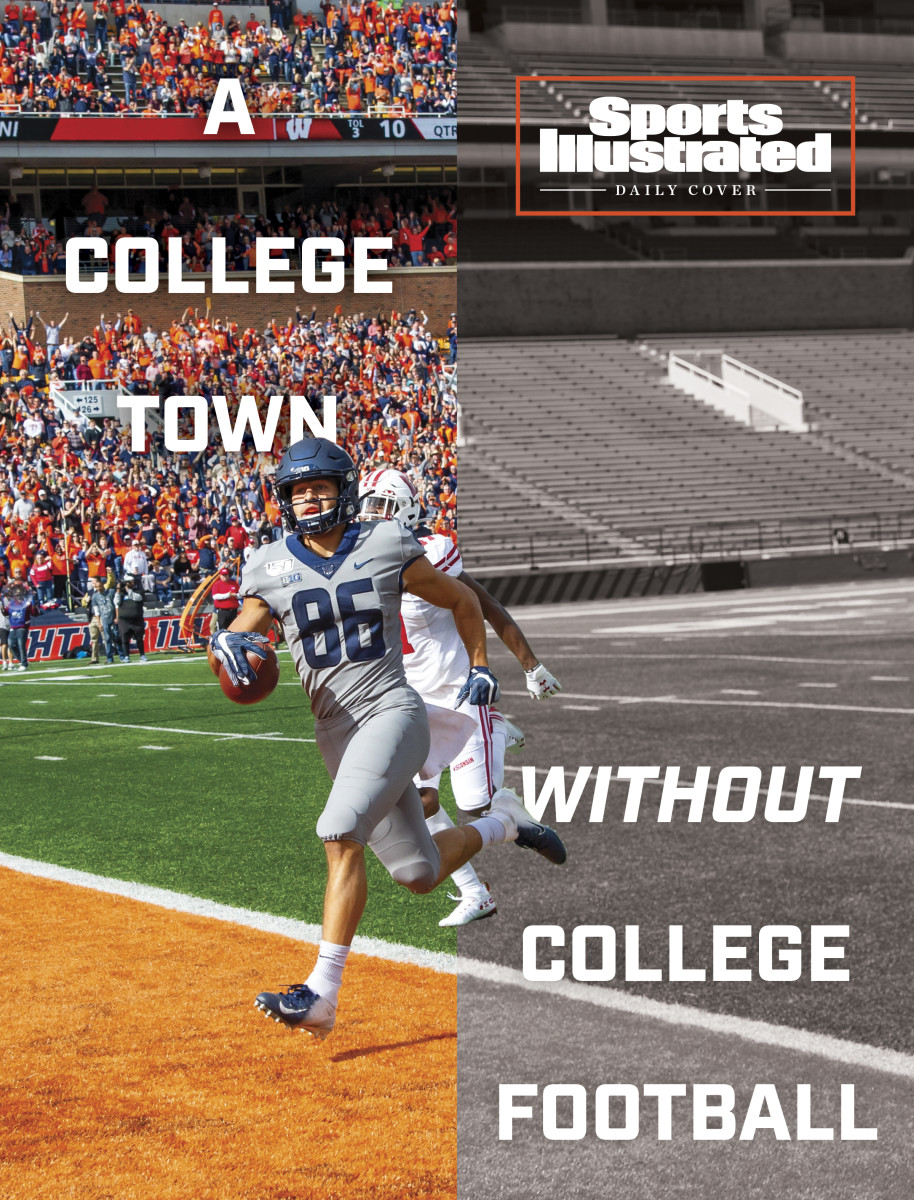

CHAMPAIGN, Ill.—Josh Whitman sat on a third-row aluminum bleacher in the corner of Illinois’s Memorial Stadium, gazing at the emptiness, pondering time and place. He played here 20 years ago, and today he is the school’s athletic director. Red Grange ran and Dick Butkus tackled in this grand old edifice, which is flanked on the east and west sides by towering columns inscribed with the names of Illinoisans killed in World War I.

Now, for the first autumn in 97 years, no football is expected to be played in this historic stadium. “We would be getting ready to go right now, wouldn’t we?” Whitman says wistfully.

They would indeed. It was 5 p.m. last Thursday, the day when the Illini were scheduled to play Ohio State here in the first Power 5 football game of the 2020 season. It would have been an idyllic college football game day—crisp and sunny in the afternoon, with a cool breeze picking up toward nightfall. Even with reduced stadium attendance, the town and campus would have hummed with a long-absent energy.

Hotel rooms would be occupied by fans of both teams. (Ohio State fans are legendary travelers in support of the Buckeyes.) The bars downtown and in Campustown would be seeing their best business in at least six months. The apparel shops would be selling blue-and-orange merch. Grange Grove, the tailgating area right outside the stadium, would have been the revelry focal point before kickoff for alums and students, flocking to food trucks and the souvenir shop.

Sitting in Memorial, Whitman could picture exactly what he would have been doing as kickoff approached.

“I generally walk down that ramp in the south end zone,” he says, pointing to the opposite end of the field. “And the first time you come into the horseshoe and see the stadium, and the crowd, standing on the sideline during warmups, watching the guys get ready to go, it’s powerful.

“I’m always on the field at kickoff and always on the field at the final gun. Opening kickoff of a football game, there are few things that can match the emotion of that moment. As a former player, I guess I still kind of crave that.”

The football cravings are going unfulfilled these virus-plagued days in Big Ten country, and beyond. Labor Day weekend, traditionally the gridiron bacchanal that kicks off four months of collegiate blocking and tackling, was reduced to a meager nine-game morsel. No big games, no big crowds.

The schedule will expand going forward nationally, but not locally. Not here. In a town of 90,000 that revolves around a university of about 34,000 students, this is one more civic blow.

The entire nation is struggling in 2020, but college towns have felt a unique squeeze—students went home in March and most did not return to campus until August, if they returned at all. After a spasm of back-to-school carelessness, the Illinois students now seem to be accepting a more cloistered lifestyle: masked up; eating carry-out and not going out; spending less time (and money) in the community.

On what was supposed to be opening night in big-time college football, this place was dead quiet. It was a depressed and depressing Thursday in the middle of America, emblematic of so many college towns. Illinois, we feel your 'Paign.

***

“Would have been a great day for a football game,” was the greeting last Thursday from Jayne DeLuce, sitting at an outdoor table at Farren’s in downtown Champaign. The indoor seating is closed, so the restaurant has adopted like so many others nationwide—annexing nearby street space and going al fresco.

DeLuce works next door, at Visit Champaign County. She is as connected as can be to the business rhythms of the area, and as connected as can be to Illinois athletics. Her father, Jim Turpin, was the radio voice of Illini football for 42 years. At the intersection of civic and campus life, these are grim economic times.

“It’s decimated,” DeLuce says. “Since the spring, three of our hotels closed temporarily. I don’t think they’re all going to make it—especially now. … Our tourism industry has been decimated by the lack of sports, conferences, group tours. It’s tough. I feel for the small business owners.

“People think about the hotels, for football. But how about the companies that do the port-a-johns outside the stadium for tailgating? What about the florist who does the flowers for receptions? The caterers? It’s terrible.”

DeLuce says an average Illinois home football game results in an estimated $3 million economic impact for Champaign County. In a normal season, that’s roughly $20 million. This was not going to be a normal season.

The original schedule called for seven home games. That was downsized to five when the Big Ten announced it was going to a conference-only format. If Illinois was able to sell tickets for 20% of capacity, that would have put roughly 12,000 fans in the stands.

So each 2020 home game might have been worth $600,000 to the county. With five of them, instead of seven, that’s about $3 million for the season—roughly the same as a single game in a normal season. That would have been a $17 million financial hit; instead it’s $20 million because there are no home games at all.

(As the numbers illustrate, the Big Ten’s decision not to play fall football—while still under siege from coaches and fans and administrators and players and parents of players—is not triggering financial ruin. COVID-19 already did that, by demolishing schedules and reducing stadium capacity nationwide. No season at all is only slightly more ruinous financially than a partial season in a mostly empty stadium.)

There were additional big sports plans that currently sit idle. Whitman worked with DeLuce and others to lay the groundwork for an arena near downtown for a new Illinois varsity sport: ice hockey. There are plenty of hockey fans in Illinois and players in the Big Ten footprint, and potentially there is revenue to be earned. The arena site is near the Amtrak station, perfect for hockey fans wanting to come downstate from Chicago for a game. But it’s the wrong time to invest tens of millions of dollars in a start-up program. “We’re going to take a little pause on that project and let the dust settle a little bit,” Whitman says.

With the support of Whitman and the university, Champaign did grab back the state high school basketball championships for 2021 after they had been in Peoria. That’s a recruiting win for Illinois basketball and an economic win for DeLuce and the local businesses—if the tournament happens. It’s scheduled, but potentially subject to downsizing.

Athletics is just part of the college-town economic downturn, of course. When a huge campus shuts down, everything in its orbit teeters on the brink. That’s why the Visit Champaign County focus has shifted completely from a tourism mindset to finding ways to support local businesses that lost their clientele.

“The loss of student spending, the loss of jobs for people who depend on student spending, the closing of businesses, it’s significant,” DeLuce says. She mentioned a local bookstore that had to develop an online presence to get by. An art supply store, dependent on Illinois art students, suddenly needed new clientele. Uber drivers, bike renters, banks near campus—the list of affected businesses keeps going.

“It’s devastating.”

***

At 8:06 p.m. Thursday, Jason Reda told his front-door staff to start deconstructing the orange fencing in front of Kam’s. There were five portable fence sections set up for crowd control getting into the Campustown bar at the corner of First & Green, but there was no crowd to control. The happy hour crowd on the rooftop patio had largely dispersed, and the ground-level outdoor area under a tent was sparsely populated.

Reda, the manager, knew that the night was all but over before it even began. As his staff took down the fencing, they discussed what the night would have been like if Ohio State were in town.

“Obviously, not having football has been a big impact on business,” Reda says, slapping his hands on his thighs. “Bad timing, but what can you do?”

Kam’s is the kind of college bar that booms in normal times, with 46 TVs lining the walls for sports fans and ample floor space for mingling. This is the new version; the old Kam’s was a multigenerational Champaign fixture that proclaimed itself “Home of the Drinking Illini” and came with an accompanying, signature college-bar odor.

Modernized and better located, Kam’s reopened in January 2020. There are team photos on the walls of every Illinois Big Ten championship football team. One room, used largely for alumni gatherings, is flush with Chief Illiniwek paraphernalia (the former mascot who was mothballed for obvious reasons). A mural in the courtyard outside features renderings of famous Illinois alums, the football stadium and basketball arena, and the signature campus alma mater statue wearing an orange Kam’s T-shirt.

There were big plans for 2020. And as we all know, 2020 has no use for anyone’s plans.

“This place is designed for football season,” says Reda, a former Illinois placekicker who holds the school career scoring record with 267 points. “It would have been nice to get this new facility broken today. Having Ohio State in town for a Thursday night opener would have been awesome.”

Instead, it was another ghostly Thursday night in a town that used to bounce on Thursday nights. Walk down Green Street, and all the other establishments were in the same straits as Kam’s. Restaurants were setting brown paper bags with to-go orders on tables, with students darting in to pick them up and then head back to apartments or dorms. Outdoor tables sat vacant in front of bars. Kitchens were closing early.

This is a recent development. Students came back to campus and enjoyed a YOLO lifestyle for the first week, but COVID-19 testing numbers told on them—after more than 400 positives between Aug. 24 and Sept. 1, the university cracked down. “We believe taking swift action to identify and remove students who refuse to follow safety guidelines is the right decision,” Illinois chancellor Robert Jones said in a statement. “We have been encouraged that the vast majority of our students have been compliant, and we believe this effort will require noncompliant students to make the choice to either comply or leave campus.”

That was Sept. 2. On Sept. 3, Green Street was almost empty. The fencing came down at 8:06 at Kam’s, and the front door was closed by 9:15.

“We’ve just got to ride it out,” Reda says. “Bars are public enemy No. 1 right now with COVID.”

At the Esquire downtown, business is basically nonexistent. The place caters more to professionals, faculty and alumni than students, but it is feeling the effects of no football on a day when there was going to be football. During the season they host a local sports-talk radio show live from their location on Mondays, and they always draw a pregame crowd.

“This is way slower than the slowest winter months,” says manager Jackie Sampson. “On game day a lot of alums just say, ‘Meet up at the Esquire.’ For an Ohio State game, we would have been completely packed.”

***

Loren Tate started covering Illinois athletics in 1966, and he’s never stopped. Now in his late 80s, Tate still does a weekly radio show and writes a weekly column for the Champaign News-Gazette and keeps his finger on the pulse of the place. He sees a fan base that is confused by the Big Ten’s tortured path through this summer.

The fall season was canceled, but the league’s failure to control the message and build unanimity has led to an ongoing PR disaster. It’s only been made worse by the fact that the Big 12, Southeastern Conference and Atlantic Coast Conference are continuing on with their seasons.

“People are looking at each other and saying, ‘What the hell is going on?’” says Tate, who believes a veteran Illinois team was poised for a breakthrough season. “There are so many rumors, and there is some despondency. There is disappointment in our leadership. We’re not leading the charge to get football back, put it that way.”

That charge is being led, somewhat maniacally, by people in Columbus and Lincoln, with some help from Marching Jim Harbaugh in Ann Arbor and James Franklin in State College. The league is suffused with anarchy and misinformation, as some schools desperately try to force a revote and (seemingly unlikely) reversal of an 11–3 decision not to play. There has been nothing to indicate that Illinois is going to change its mind and vote to play, but it would be a surprise if the Illini opted against a fall season should one come to pass.

Against this conflict-tinged backdrop, the Illinois leadership is keeping quiet. Whitman just wants his fall-sports athletes to stay the course and stay ready.

“We didn’t get a ton of notice when we hit the stop button, and we may not get a ton of notice when we hit the start button again,” he says. "So we better all be prepared for when that time comes. … And they’ve been great about that.

“We’ve said to them, if you became a Big Ten student-athlete and came to compete at the University of Illinois, you’ve already made the decision to make a lot of sacrifices. This is just another example of things you have to do that are a little bit different from the people who live down the hall from you—you can’t go out on Thursday nights, you can’t stay up playing video games until 2 in the morning, you can’t get bad grades. Those are all things that have been true forever, and now you layer on top of that some of these COVID issues, and it’s just one more thing you have to do to be a successful athlete here. You’ve already made the choice to come through the narrow path.”

Eventually, that path will empty out into a stadium, and Illinois will play football again. When? Nobody is sure. But Whitman will be on the field for that opening kickoff.

“I daydream about that,” he says. “I think it will be emotional. I really do. I think the first time I see the ball kicked off in this place, I’ll feel a tremendous sense of excitement and probably some relief. And some satisfaction, and appreciation. Whenever that moment comes, it’s going to be the culmination of thousands and thousands of hours of work by hundreds and hundreds of people.”

Without football, time has passed in the strangest ways. Without preseason camp, it still feels like July in Champaign. Days have dragged by, but months seemed to disappear in a blink. From the confines of the upstairs office in his house, Josh Whitman has found an unusual way to measure the duration of the pandemic.

“We have a [Zoom] meeting with one of our senior leadership groups every Tuesday morning,” he said. ”The civil defense siren goes off the first Tuesday of every month at 10 o’clock, right in the middle of these meetings. So every month it goes off and I’m still sitting there. I remember thinking in May, ‘O.K., let’s see if I’m still sitting here in June.' Then June, July, August. Every month, that stupid siren goes off.”

The siren went off again last week. September had arrived, but football had not.

Read more of SI's Daily Covers stories here

More NCAA Football Coverage From SI.com:

What We'll Miss About Penn State's Beaver Stadium This Fall

How Social Media Created A BLM Protest Led By Illini Players

Herm Edwards Giving ASU Players Chance to Register to Vote