Why Aren't More People Talking About the Ohio State Sex Abuse Scandal?

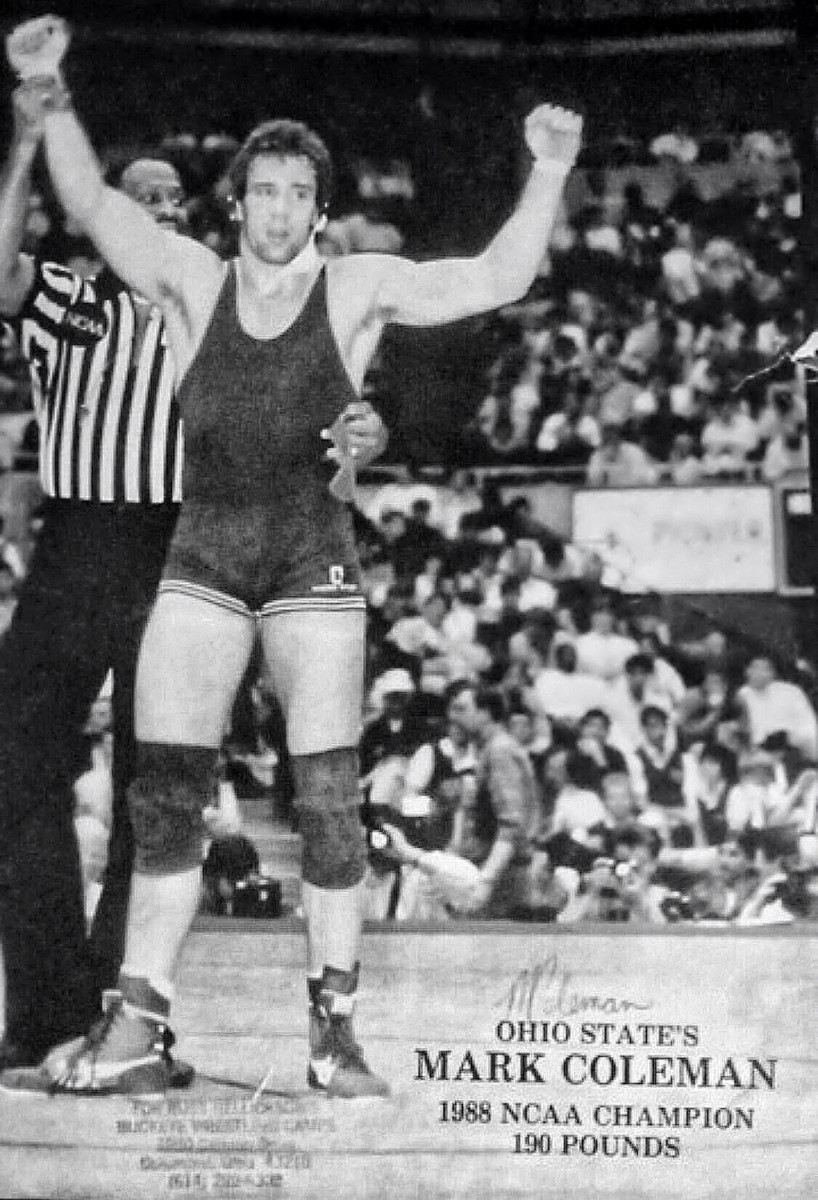

The most sweeping sex abuse scandal in the history of American higher education—to say nothing of the history of college sports—played out over nearly 20 years on one of the largest campuses in the country. Most of the survivors were athletes. Most of them didn’t entirely grasp until later in their lives that they had been assaulted and raped. Most of them were like Mark Coleman, whose interactions with Dr. Richard Strauss would create a smog, lingering over his life for decades.

A native of Fremont, Ohio, Coleman was an All-America wrestler at Miami of Ohio before transferring to Ohio State in the fall of 1986 for his senior season. Having played competitive sports his entire life, Coleman had experienced enough preseason athletic physicals to know the minor discomfort they entailed. But he was completely unprepared for what came next as he stood alone in a room with Strauss, then the official doctor for five OSU sports programs and consulting physician for at least 10 others. Strauss asked Coleman to undress and, under the guise of a medical examination, inappropriately touched Coleman. “He examined me pretty good. It was an eye-opener,” Coleman says, pausing. “I don’t want to go further than that.”

At practice, Coleman inquired about Strauss. His questions were greeted with levity and laughter. The slightly-built doctor with the heavily gelled hair who could be alternatively charming and prickly, and spoke in an effeminate voice edged in awkward nervousness? Who would not only lurk during practices, sitting naked on locker room benches, but then shower alongside the athletes? Who fondled athletes’ genitals during examinations, regardless of their injury? For years, Strauss and his “handsiness” as more than one former Buckeye athlete put it to Sports Illustrated, made for both an open secret and a running joke within the OSU athletic department.

So much so that each sport seemed to have coined a different shorthand for Strauss. For athletes in one sport he was “Dr. Feel Good.” For another, he was “Dr. Jelly Fingers.” There was also “Dr. Balls,” “Dr. Nuts” and “Dr. Drop-Your-Drawers.” Some OSU coaches used the mock threat of “having to see Dr. Strauss” as motivation to make their athletes run faster or practice harder.

Coleman was new on campus, new to the wrestling program. And the team doctor was, well, the team doctor. As a varsity athlete on scholarship, Coleman wasn’t inclined to, as he puts it, “stir shit up.” And, like most OSU athletes, he didn’t fully process that he had been sexually assaulted. For one, it was the late 80s, still a benighted era for sexual assault awareness, much less same-gender assault, when comprehension and vocabulary didn’t exist. “We never thought a man could sexually abuse a man,” says Coleman. “We just played it off. We joked about it. But I don’t think we were really joking.”

Coleman was also confused, ashamed and embarrassed, and a novice adult trying to balance sports and studies, inclined to believe and trust a team doctor. “This guy controlled my future,” Coleman recalls. “We all put up with it. For me, it was like, just clear me so I can go win an NCAA title and make the Olympic team, you know?”

Coleman would do both. He’d go on to win the NCAA wrestling title in 1988, and would compete in the 1992 Olympics in Barcelona, finishing seventh. He would then marry his ground skills with boxing, kicking, knees, elbows and head-butts and reinvent himself as a fearsome mixed martial arts fighter. Nicknamed “the Hammer,” Coleman would become the UFC’s first heavyweight champ. For all his successes, he was haunted by Strauss.

Now 55, Coleman recalls his spasms of rage, inexplicable at the time: “I didn’t know how bad it was affecting me, but now I look back and I was very angry. I went into practice very angry a lot of times, storming into the wrestling room and screaming. I was confused. I spun it as, well, it’s good to be angry, I’m gonna have a hell of a practice and kick someone’s ass. But now I realize, it wasn’t good and I realize why.”

All the locker room banter and nicknames masked the reality. Dr. Richard Strauss was a serial sexual predator, an unchecked terror, stalking the Ohio State campus for nearly two decades. And his power over young athletes, Sports Illustrated has learned, was even greater than previously known. Four independent sources confirmed that Strauss was a major source on campus for performance-enhancing drugs and frequently counseled athletes on how to use them. There is no known connection between Strauss's decision to abuse an athlete and whether he furnished him with PEDs—Coleman, for instance, confirmed first-hand knowledge that Strauss discussed the topic with athletes but adamantly denied that the doctor provided him with steroids. But sources tell SI that Strauss’s distribution of banned and illegal drugs gave him significant leverage over many athletes and potentially some coaches, likely helping to conceal his abuses.

Strauss’s victims would span two decades, from 1978 to 1998, and include athletes who would go on to play in the NFL and fight in the cages of UFC. They would include athletes in nonrevenue sports from tennis to wrestling to cheerleading. They would also include—critically, it would turn out—male undergraduates from the general student population, unencumbered by the OSU athletic department, the athlete culture, or fealty to “Buckeye Nation,” making them more likely to speak out. Strauss had access to them all. According to a report commissioned by Ohio State, before he was done, he would commit at least 1,429 instances of fondling and 47 instances of rape.

The scale of Richard Strauss’s abuses was comparable to those of another Big Ten doctor who assaulted athletes, Larry Nassar, the central figure of scandals encompassing Michigan State and USA Gymnastics. Why, then, has the OSU scandal drawn a fraction of the same attention and national outrage? Why is Ohio State taking a strikingly hard-line stance with so many of the 350-plus survivors, including Coleman, who have sued the school? And why are former OSU athletes negotiating settlements for dimes on the dollar, measured against the amounts received recently by the victims of Nassar and other campus predators?

One likely answer: because of the same collision of factors and social norms that enabled Strauss’s predatory behavior to persist for so long in the first place.

***

Richard Strauss was crowding age 40 when he came to Columbus in 1978 as an assistant professor in the college of medicine. His reputation was as impeccable as his pedigree. After receiving his medical degree in 1964 from the prestigious University of Chicago, Strauss served as a medical officer on a nuclear submarine. He spent the next 14 years practicing medicine at various colleges and universities, including Penn and Harvard.

“He was a very bright guy—as you would expect from a full professor at a major medical school,” says Dr. Charles Yesalis, a longtime Penn State faculty member who knew Strauss through conferences and once co-authored an academic article with him. “He was well-rounded, not [academically] a one-trick pony.”

While Strauss was no athlete and weighed barely 140 pounds, not long after he was hired at OSU, he began volunteering to work with OSU teams at Larkins Hall, then the school’s main physical education building. Witnesses—and some of the few remaining records—reveal that it was also not long before he began his reign of sexual abuse. Many sexual predators groom their targets over a period of years, building relationships and trust before committing their violative acts. Jerry Sandusky, the disgraced Penn State assistant football coach, is a classic example. In Strauss’s case, he was more brazen and less patient.

Joe Bechtel was a freshman in the fall of 1979, a hockey player on partial scholarship. Playing sports at OSU was not only a dream realized, but a continuation of a family tradition. His father had played football for OSU under Woody Hayes. After contracting mononucleosis as a sophomore, Bechtel visited Strauss to be examined. “I needed him to clear me so I could get back to playing,” Bechtel recalled to SI. “The coach was going to take the doctor’s advice.”

In the course of the examination, which Strauss performed alone in his office, the doctor fondled Bechtel’s testicles. He also volunteered that his medical research was in sperm production. Bechtel recalls feeling deeply uncomfortable by Strauss’s examination. But not completely surprised.

At an OSU hockey game that season, Strauss served as the doctor on call for both teams. Bechtel recalls being in the training room for postgame treatment when a member of the opposing team entered, complaining of a toe infection. Strauss instructed the player to drop his pants, in front of all present, and began groping his penis and testicles. When Bechtel informed the team’s trainer about the doctor’s inappropriate behavior, it triggered a joke about the creepy new doctor.

Around the same time, Dave Mulvin, captain of the OSU wrestling team, was fondled by Strauss during a physical. He abruptly ended the exam, saying to the doctor that his behavior was “weird.” Mulvin says he went to the student health center to finish the exam with a different doctor and explained what had happened with Strauss. His account, he says, was shrugged off.

As was another Strauss interaction with an OSU athlete from the same sports season, recounted in a lawsuit. A two-sport athlete on OSU’s wrestling and football teams––who has requested anonymity––saw Strauss in early 1979, after the athlete became dehydrated from a prolonged training drill. His urine was discolored, and he was in serious pain on account of a kidney infection. Trainers in Larkins Hall noticed that the athlete looked “extremely ill” and summoned Strauss. When the other trainers had left the room, Strauss gave the athlete what he said was pain medication.

Soon, the athlete says he began to feel groggy, like he was going to pass out. But Strauss told him to pull his pants down. Positioned behind the athlete, Strauss began raping him. As the athlete came to, Strauss asked him, “Are you okay?”

The following day, the athlete says he reported the sexual violation to OSU’s wrestling coach, Chris Ford. According to the lawsuit, the athlete and coach had an explosive argument, with Ford telling the athlete he would take care of it. But there was no follow-up, and instead of helping the athlete, Ford “shunned and blacklisted” him, kicking him off the team.

Ford died in 2016. In response to a detailed set of questions from SI, Ohio State replied with a general statement, similar to others the university has made on Strauss. “We express our deep regret and apologies to all who experienced Strauss’s abuse,” the statement read, in part. “Ohio State is a fundamentally different university today and over the past 20 years has committed substantial resources to prevent and address sexual misconduct.”

For two decades, though, Strauss’s abuse continued unchecked, the roster of affected athletes growing each year. Freshman arriving for routine physicals would end up having their penis and testicles pawed. Athlete after athlete came to see Strauss for sore throats and headaches and foot injuries; and left having been fondled or otherwise assaulted. Nick Nutter, an All-America OSU wrestler in the 1990s, recounts that he made a simple calculation before deciding whether to see Strauss: “I turned a blind eye to injuries because I didn’t want the co-pay to be a stroking session,” he says. “I would ask myself: Is this injury bad enough that I’m willing to get molested for it?”

***

As Strauss surely recognized, it would have been hard to scheme a set of circumstances more conducive to serial sexual abuse. His position as a doctor allowed him to cloak his assault as legitimate treatment, mirroring the tactic employed by Nassar as he preyed on gymnasts.

“If Richard Strauss had done what he had done in a bar or in a back alley, I think many of the survivors would have responded differently,” says Kristy McCray, an Otterbein (Ohio) University associate professor of health and sports sciences, specializing in college sport and sexual violence prevention. “How do you punch a doctor in the face when he’s [claiming to be] ‘treating’ you?”

Strauss’s mere title of doctor conferred a level of status and authority. He was not only certified by OSU, but he became a member of the medical commission of the International Olympic Committee. He was smart and manipulative,” recalls Nutter. “When I did question him—‘You really need me to undress me to treat my elbow, Doc?’—he’d say, ‘Nick, I’m a doctor. Who are you to question me?’ ”

And in the dynamics of college sports, he held the ultimate gatekeeping power over his victims: Athletes required his clearance before they could play their sport, often the reason they were at OSU. For instance, Michael Murphy, a Buckeyes pole vaulter violated by Strauss in the late ‘80s, worried that without his scholarship, he wouldn’t have been able to afford to continue as an OSU student. “Strauss,” Murphy says, “held all the cards.”

For some athletes, Strauss may have held more than cards. Apart from his avowed specialization in sperm research, Strauss was also an expert—a pioneer, even—in the field of steroids. While mainstream sports medicine experts were still waking up to the powers of anabolics, Strauss was publishing a series of academic articles on PEDs in respected journals like the Journal of the American Medical Association, or JAMA. According to multiple former OSU athletes, Strauss was a source for PEDs and a fount of knowledge on their use.

Rocky Ratliff, a former OSU wrestler, is now an Ohio-based lawyer representing 46 former Buckeye athletes. (Ratliff, too, was assaulted by Strauss and has a claim against the school, but he is not representing himself.) Ratliff asserted to SI that multiple clients of his “received and/or witnessed Dr. Strauss administering steroids and/or performance enhancing drugs to athletes at OSU in order for the athletes to get an edge.” Ratliff says that his clients include former OSU hockey players and that Strauss was “straight up” with them. According to Ratliff: “Strauss would say, ‘Hey you’re having a hard time on the ice? I got some s--- for you. I can give you steroids and help you out.’”

One of the John Doe plaintiffs—who has yet to settle with OSU—was a student athletic trainer for Ohio State in the late ‘80s. He recalls transporting steroids that Strauss had prescribed from the Student Health facility to the training rooms. “It was clear that [athletes] were rats and he was running a lab,” the trainer says. “There were corticosteroids steroids and anabolic steroids. Corticosteroids were used for anti-inflammation. But we used anabolics to make you bigger. It was viewed as a competitive advantage. How much was Strauss [prescribing]? I know he had them and I know he was using them on some athletes.”

The trainer stresses that this was the early days for steroids in sports and, as at most schools, the OSU drug-testing protocols were lax at best. Asked about the notion that Strauss held sway over athletes because he was prescribing them PEDs, the trainer says: “Yeah. I’ll make you bigger. I’ll make you a better performing athlete. But you have to do what I say. And coaches weren’t going to rock the boat too much on that, either.”

Another former wrestler, who wishes to remain anonymous, echoed the trainer’s account, saying that Strauss personally dispensed steroids to athletes.

An Ohio State spokesperson declined to comment specifically on these claims, referring to a line in a report the school commissioned from the law firm Perkins Coie on Strauss stating that the firm’s investigators received one second-hand report that Strauss provided steroids, but they could not corroborate it. (The spokesperson added that the university encourages individuals with information to reach out to its Office of Compliance and Integrity.)

It was significant, too, that Strauss’s survivors were male athletes, another factor that brought the shroud of secrecy. The notion that the alphas of campus—all-American wrestlers and NFL-bound football players—could be sexually abused by a man? It was almost impossible for many to reconcile, not least some of the survivors themselves. Joe Bechtel, the hockey player, would later recall that he didn’t look into reporting Strauss for fear of “being called a pussy” or suspected of being gay.

A former tennis player who was abused by Strauss puts it this way: “In the 1980s, in a college sports environment, getting sexually abused by a man was just beyond something people could even comprehend. Even now, it’s like I don’t get it. Why didn’t you kick his ass? It’s hard for people to wrap their brain around [same-gender assault], especially when the victim is an athlete in their physical prime.”

Coleman hears this same question and he, too, winces. “People say, Why would they let a little man do this? Well, it’s complicated. You felt powerless. I wasn’t going to stir up s---, punch Dr. Strauss in the face and risk everything.”

This doesn’t surprise Keeli Sorensen, vice president of victim services for the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network (RAINN), a nonprofit anti-sexual assault organization. “It’s a big fallacy that someone should automatically be fighting,” she says. “It doesn’t work that way. You are not thinking. You are surviving. It is normal to freeze...But because we have such an ugly trope about what men should do, there comes shame and guilt for not having done it. Which makes it that much worse.”

McCray, who received her PhD. from Ohio State and now lives in Columbus, says that asking Why didn’t you fight? goes to basic myths about rape, and same-sex rape specifically. “It’s very clear that middle-aged Jerry Sandusky should not be showering with a 10-year-old boy. That is clearly wrong. Nobody supports that. Nobody supports Larry Nassar abusing young girls. It is abhorrent,” she says. “But when it comes to adults—both men and women—when we think about adult victimization, societally, we are more likely to engage in victim blaming. Why didn’t you fight back? Why didn’t you stop him? And then the extension of that with male victims is it makes us uncomfortable to think that this can happen to someone like me, someone like my dad, someone like my brother….Now add that these were not weak, soft men. These were highly competitive, physically strong athletes.”

It also worked to Strauss’s advantage that he operated in a college environment. For all the seminars and orientation programs, campuses remain hotbeds for assaults. According the Department of Justice data, male college-aged students (18-24) are 78% more likely than non-students of the same age to be a survivor of rape or sexual assault. “There is still a lack of open conversation about men being sexually assaulted and what risk looks like,” says Sorensen. “it’s not necessarily physical violence or attack by a stranger.”

Maybe the ultimate factor enabling Strauss: the lack of oversight at Ohio State, and the repeated failure of administrators to investigate. The first documented complaint against Strauss was lodged in 1979. Formally and informally, concerns about Strauss would continue for years. More than 20 OSU coaches would later assert that they were aware of rumors and grievances. Coach after coach used the term “open secret” to describe Strauss. Nothing was done.

***

In 1994, the “open secret” was finally aired when Ohio State’s fencing coach, Charlotte Remenyik, approached Strauss’s boss, Dr. John Lombardo, medical director of Ohio State sports. She expressed concern that Strauss was giving unnecessary genital exams to male athletes.

In a document obtained by SI, Lombardo—who, since 1990, has moonlighted as the NFL’s drug advisor for anabolic steroids and other performance-enhancing drugs—then wrote to Paul Krebs, OSU’s senior associate athletic director, making him aware of the fencing team’s complaint. But in the same letter, Lombardo dismissed the claims as lacking merit, writing that they were “based on rumors generated over 10 years with no foundation.” Strauss volunteered to discontinue working with the fencing team, and the matter was not reported outside the athletic department. (Krebs would go on to become athletic director at the University of New Mexico where he would be charged with seven felony counts including fraud, money laundering and other felonies. His trial is scheduled for October 2020.)

Around the same time, in the spring of 1994, Strauss proposed to OSU that he initiate a men’s clinic for student health services. Though Strauss was facing multiple complaints from OSU students, including the fencers, Ohio State granted this request. “Predators are very good at getting access to their prey,” says Ilann Maazel, a New York-based attorney at Emery Celli Brinckerhoff who represents 93 of the survivors. “His method was to use the state university to get access.”

At the clinic, complaints against Strauss mounted. On Jan. 3, 1995, a student reported Strauss to student health services director, Dr. Ted Grace, saying that the treatment he received from Strauss was “inappropriate for the problem he had come in for.”

On Jan. 6, 1995, just three days later, another OSU student, Steve Snyder-Hill, complained to Grace that Strauss “had come to him and tried to pick him up during an examination.” What’s more, seeking treatment for a breast lump, Snyder-Hill was subjected to testicular and anal examination. Snyder-Hill also says Strauss had an erection during the exam and pushed against him.

In a letter dated January 26, 1995, Grace wrote to Snyder-Hill, responding to the students’ concerns. Though mere weeks earlier another student had raised strikingly similar issues about Strauss, Grace asserted, “I want to assure you that we had never received a complaint about Dr. Strauss before, although we have had several positive comments.”

On July 1, 1995—months after multiple complaints were filed—Strauss received a performance evaluation from his bosses and supervisors, including Grace. His overall evaluation was “excellent.” The report characterized Strauss as “a guiding force in the program development [who] always keeps the patients’ needs first,” adding that “I look forward to many more new and creative steps in the men’s clinic.” There were no references to any complaints.

Asked the following year by OSU attorneys why Strauss would receive such a glowing review without even making reference to multiple complaints, Grace wrote, “for legal reasons, we would never mention a serious allegation against a physician on their evaluation form, which is a permanent part of their personnel record. There were no lies in the evaluation. Dr. Strauss is a highly competent, dependable, knowledgeable and thorough clinician.”

Snyder-Hill’s complaint and letter to Grace would never be mentioned in Strauss’s personnel file. And years later, testifying under oath in a deposition, Grace would say that he had taken his files concerning Strauss to his home. Where he later shredded them. (Contacted by SI for this story, Grace, now the director of Student Health Services at Southern Illinois University, responded, “I appreciate the offer, but I don’t have any comment at this time.”)

In 1996, yet another OSU student filed a complaint against Strauss after a prolonged examination at the clinic led the student to ejaculate. The student stormed out of the examination, yelling to other students in the waiting room that Strauss was a “pervert” and warning them to “get out of there right away.”

This time, the university placed Strauss on administrative leave and scheduled hearings to determine whether he should be fired. Strauss responded by threatening legal action against the student and the university. In a letter to David Williams II, OSU’s vice president for student affairs, Strauss denied inappropriate behavior, writing: “It is unfortunate that the patient ejaculated in my office, but that’s his problem, not mine.”

In July of 1996, quietly—but without public disgrace—Strauss was dropped from his Student Health Services position and stripped of duties in the athletic department. OSU cited “three complaints by students in a period of 13 months.” Strauss protested this removal from the athletic and Student Health departments, even appealing to then-President E. Gordon Gee. (There are no public records as to whether Gee responded.)

In an apparent act of desperation, Strauss also filed a report against Grace, his boss, to the state of Ohio Medical Board. Only while investigating Strauss’s complaint against Grace, did the Medical Board learn about Strauss’s predations. Grace told the board, “There are many male athletes that have been abused by Dr. Strauss.” Askled, later, what he meant by “many,” Grace, said, under oath, “Three, four, five, six. Whatever.”

Despite being dropped from the athletics department, Strauss was told that he would remain on campus as a tenured professor. No formal reports were prepared. No state of Ohio licensing personnel were notified. Still on the OSU faculty and payroll, Strauss opened a private men’s clinic in Columbus. He advertised his new clinic in the OSU campus newspaper, The Lantern, offering a student discount.

A nursing major and OSU senior, Brian Garrett worked at the clinic, lured, he says, by Strauss’s promises that he could help him with graduate school admissions. “He was very persuasive,” Garrett says of Strauss. Garrett noticed immediately that Strauss kept little paperwork or charts and ministered to Ohio State athletes. “He brought them in one door and out the other,” Garrett recalls. “He would tell me, ‘It’s not on the schedule. Just a private exam.’”

Garrett says that on his third or fourth day on the job in the summer of 1996, Strauss assaulted him as well, attempting to feel his groin when Garrett complained of heartburn. Looking back, he is struck by the power imbalance. “He got off on control,” says Garrett. “Here’s this little frail guy and he has control over this big athlete. They can’t do anything to me and I can do what I want to them.”

Garrett believes it’s not coincidence that while Strauss went unchecked for more than 15 years in the athletic department, the complaints mounted once he assaulted male students within the general student population. “Sports is more of a tough-guy, manlier environment. Suck it up if you get assaulted or abused,” Garrett says. “At the student health clinic, they aren’t necessarily on scholarship so they’re not as afraid to speak up.”

With still more complaints pending, Strauss retired voluntarily from OSU in 1998. Upon his retirement, Strauss was conferred the honorific emeritus status by OSU. After years in Columbus, he left central Ohio and moved to Southern California. His last listed residence, an apartment in Venice Beach, Calif., was a block from the Pacific Ocean. He reportedly volunteered at a medical clinic near Hermosa Beach that treats an underserved population. In mid-August of 2005, beset by depression and abdominal pain, at age 67, Strauss took his own life.

***

It took an unlikely set of circumstances for Richard Strauss’s predations to surface publicly and go from a sort of family secret held within OSU athletics, to a full-blown scandal. Mike DiSabato was victimized by Strauss as a high schooler in Columbus when—under the guise of conducting research on the body fat of high school wrestlers—Strauss administered an unnecessary genital exam. DiSabato went on to become an All-American wrestler at OSU, where Strauss continued to abuse him. After graduating, DiSabato started a licensing apparel business that produced Buckeyes merchandise. When OSU severed ties with him in 2006, however, DiSabato made a full-time job of needling the school, even suing over the licensing dispute (the case eventually settled).

In early 2018, with the #MeToo wave cresting, DiSabato sent an email to OSU making references to Strauss’s serial abuse. By early April, the university realized that the allegations were explosive and a major sex abuse scandal was brewing. It retained a local law firm which then retained the prominent Seattle-based law firm Perkins Coie to conduct an independent investigation.

In the meantime, DiSabato had grown impatient, also approaching the Columbus Dispatch. On the same day that the university announced its investigation, he was quoted in the paper: “The young gymnasts at Michigan State who showed amazing courage have awakened many who have had enough of a system which fosters and supports deviant sexual predators,” he said. A firehose of candor with connections within Columbus and the OSU alumni network, DiSabato courted the media, reaching out personally to reporters, and was happy to add accelerant to the fire.

To avoid retraumatizing those affected, the Perkins Coie investigators did not actively pursue leads, asking simply that anyone affected or interested in speaking should establish contact. Even with those limiting parameters—and therefore, likely, interviewing only a small fraction of Strauss’s survivors—the report was, in the words of Ohio State’s president at the time, Michael V. Drake, “shocking and painful to comprehend.”

Released in May of 2019 and conducted at a cost of $6.2 million, the report detailed acts of sexual abuse Strauss had committed against 177 former students. Most of them were athletes and most were listed anonymously as John Doe. “We know that a tremendous number of people do not want to come forward for so many reasons: fear, shame, humiliation,” says Maazel. “I think it's highly likely that the number of survivors is many multiples of the people who have come forward.”

The report also concluded that “university personnel had knowledge of complaints and concerns about Strauss’s conduct as early as 1979 but failed to investigate or act meaningfully.” Perhaps most damningly, the report cites more than 40 Ohio State coaches and administrators and athletic directors who did not respond adequately, going all the way to Andy Geiger, the OSU athletic director from 1994-2005, who has told the Columbus media he doesn't recall any complaints of Strauss’s sexual misconduct during his tenure.

Predictably, the Strauss scandal has triggered lawsuits. There have been at least 18 of them to date, encompassing more than 350 former OSU students. They are suing their alma mater, mostly on Title IX grounds, alleging the school knew about the abuse and failed to act. Brian Garrett, the nursing student assaulted by Strauss in 1996, is the named plaintiff in one suit. Stephen Snyder-Hill, the student assaulted by Strauss in 1994, attached his name to another. DiSabato joined with 36 other former athletes, the majority of them football players, and was the named plaintiff on one suit. (He was the only former OSU athlete in his class who chose to use his name.)

After the release of the Strauss report, Ohio State responded with a series of public statements and emails, projecting remorse and accountability and referring to “the university of today,” differentiating it from the university that allowed one doctor to traumatize so many students. As then-OSU President Drake wrote to OSU alumni and former Buckeye athletes on May 17, 2019, “Strauss's actions and the university’s inaction at the time were unacceptable.” The school also offered to cover the cost of counseling for those impacted by Strauss.

But OSU adopted a different tone in litigation. The school’s first line of defense was that there could be no valid lawsuits because Ohio’s two-year statute of limitations on a Title IX claim had long since lapsed. It fell to the survivors to make the argument that the statute of limitations couldn’t run until the injured party knew a crime had been committed. If OSU covered up Strauss’s abuse for decades, shielding the survivors from knowing the school could be at fault, how could the clock on filing a lawsuit already be ticking?

In May, OSU announced that it reached a settlement with almost half the former students and athletes, including DiSabato. The 162 plaintiffs agreeing to the settlement, many of them former football players, received a combined $41 million, roughly $250,000 per victim. (The same month the settlement was announced, Michael Wright, an Ohio attorney who negotiated for the former Buckeyes athletes had taken another case: a University of Michigan team physician stood accused of sexually abusing athletes.)

It was among the largest settlements OSU ever paid. Yet if Michigan State had, crassly, “set the market” the previous year for institutional neglect in a sex scandal involving a predatory doctor and abused athletes, this was a perplexingly low settlement. The 332 victims of Larry Nassar drew from a settlement pool of $425 million, an average of almost $1.3 million per claim.

“All the guys talk about it,” says Garrett, who was not among those settling his claim. “If we were women it would be a different story and it would have been over a long time ago. And the Ohio state legislators [who approved the settlements] would have taken up our cause much harder than they did. Most of them are men and it makes them uncomfortable hearing about sexual assault among men.”

Survivors acknowledge there are material distinctions between their case and what happened at Michigan State, not least that their tormenter is dead and they’re deprived of being able to dramatically confront him in court. But they also can’t help but wonder why their drive for justice has moved so slowly, why Ohio State has been so intransigent in their eyes, and they reach one irreducible conclusion.

“There’s no way society as a whole is going to look at wrestlers and football players the way they do five-feet-tall gymnasts,” says Ratliff, the lawyer and former OSU wrestler. “I don’t think society is ready for that.”

***

The assaults may have been laughed off. The persistent complaints against Strauss may have been taken so casually that records, if they existed at all, often had been destroyed or lost. But the damage was profound. The Buckeyes football player and wrestler who was raped by Strauss in 1979? Shortly after the incident, by his own admission, he began getting into fights, abusing alcohol and missing classes. Witnessing this decline, Earle Bruce, the football coach, required him to get a mental health evaluation. By his junior year, the athlete quit the football team and dropped out of OSU.

While training for the Olympics and the UFC, Mark Coleman often stayed in Columbus and worked as an OSU assistant wrestling coach. An astonishing number of wrestlers quit the team, but Coleman figured they simply couldn’t handle the rigor of wrestling. Now he has a different perspective. “These were guys on full scholarship who could have been All-Americans. Why did they quit? We thought they [wimped] out. Well, now it makes total sense. I was shocked to find out how bad [Strauss] messed guys up.”

Michael Murphy, the former OSU pole vaulter, can relate as well. When, as a freshman, he injured his hamstring he, reluctantly, saw Strauss. The doctor instructed Murphy to lay face-down on the table, then applied lubricant and penetrated Murphy’s rectum with his finger. Strauss instructed Murphy to relax and explained that he was performing “a treatment” and probing for “tissue damage.”

While Murphy’s hamstring healed, the fallout from this act of molestation worsened. Murphy became depressed, his grades tanked, and he eventually dropped out of OSU. He transferred to the Naval Academy, mostly because it was free, but he left before completing a degree. Murphy told no one about the assault. He says his father told him not to come home, unable to understand why his son was floundering.

Nick Nutter, the former All-American wrestler, says that there is emotional pain, but the physical pain he experiences today is also a legacy of his time at OSU. “I had lower back injuries [in college] that I didn’t want to tell the doc about because I didn’t want to see him. Today, the doctors tell me that at age 46, I have a 75-year-old man’s knee. Father time is catching up to me. All the times I said, ‘Will this go away or do I really need to go see doc?’ It’s catching up to me.”

The Perkins Coie report doubles as a compendium of personal tragedy, of potential drained and lives damaged. Dozens of athletes told the investigators their stories, and while each came with a slightly different fact pattern, the same theme rang out. A young athlete came to OSU, flush with ambition and optimism. He was assaulted by Strauss. He spiraled downward.

The scandal has imbued the former athletes with ambiguous feelings toward the school. This terror had happened at the Ohio State, a school many had supported since they were kids, a school that conferred on them a scholarship. DiSabato, for instance, has worn his scarlet-and-gray letterman’s jacket to hearings, a symbolic gesture that he still considered himself part of the tribe. Multiple other former Buckeye athletes commented for this story that it’s been a decades-long challenge, cordoning off happy memories and school loyalty, from the trauma they experienced there and the sense of betrayal that followed.

The scandal and its aftermath has also caused a rupture within OSU athletic programs, particularly the wrestling team that counts more than 50 alumni among Strauss’s victims. Echoing DiSabtato’s allegations, Coleman accused Jim Jordan, an OSU assistant wrestling coach from 1986 to ’94, of ignoring Strauss’s abuse, “unless he got dementia.”

Jordan, now a powerful Ohio congressman, issued a fierce denial. Coleman then walked back his comments. “It tore the whole community apart,” says Coleman. “Wrestlers are very tight. OSU wrestling is like a family. But people had to pick a side. DiSabato’s side or Jim Jordan’s side.”

The OSU wrestlers remain split on who knew what and when they knew it. Meanwhile it’s telling—a testament to the discrepancy in media treatment from the Michigan State and Penn State scandals—that the tangential involvement of Jordan marked virtually the only time the Strauss scandal became a national news story.

For many of the athletes, the scandal has been cathartic––memories and emotions, suppressed for decades, finally confronted. “It’s almost like this hole has broke,” says Murphy, now 51. It now makes sense to him why he didn’t want his two kids to attend OSU. Or why he always put off getting his annual physical. Or why he was always nervous when his kids went to a pediatrician. Painful as it was, it was also a relief to tell his wife, and even his two kids, about being assaulted.

And the scandal has been brutal––memories and emotions, suppressed for decades, that have come screaming back. Multiple survivors, athletic men deep into middle age, dissolving into tears as they rehash incidents from their late teenage years that have anguished them ever since. Some say they can’t sleep. Others have begun taking anxiety medication. More than one concedes his sexual performance has been compromised.

Among the smear of emotions, guilt figures prominently. “I’m a team player who always looked out for my teammates and my family,” says Bechtel, the former hockey player. “I would take a bullet for people. That so many people had to be subjected [to Strauss], and I didn’t stop it? It makes me pissed.”

Says Ratliff: “I have clients who can’t even look at me. They’ll sit there and cry and say, ‘I was 20 years before you. There’s no way you should have been molested.’”

Shame persists, too. Decades after assaults, the vast majority of the survivors requested anonymity when speaking to the Perkins Coie investigators. Fear is also part of the equation. Garrett, for instance, still doesn’t like going to the doctor. He says that when the story of Strauss first broke, immediately he vomited. He has slept only fitfully since.

The wrestler and football player who was raped by Strauss in 1979 is identified in his lawsuit as John Doe 32. Now in his early 60s, he says he continues to experience extreme and regular anxiety and finds himself “continuously haunted by Dr. Strauss’s abuse.”

And as much as the victims talk about “closure” for themselves and accountability from Ohio State, both remain elusive. Nearly 250 athletes have claims pending, as court-ordered mediation has failed. Strauss may be long dead, his crimes decades old, and yet somehow he remains a fresh and undiminished figure. “I see him every day,” Bechtel says. “Unfortunately, I see him every day.”