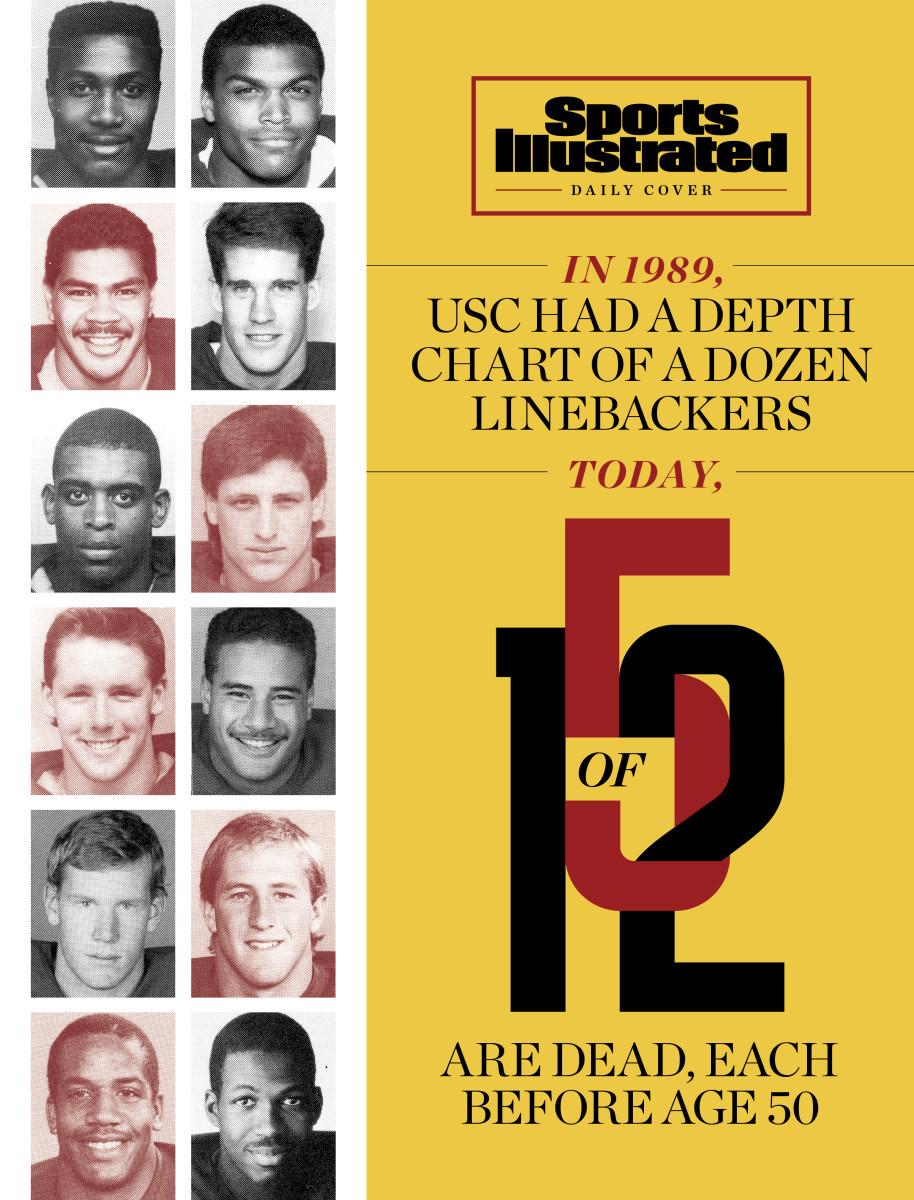

In 1989, USC Had a Depth Chart of a Dozen Linebackers. Five Have Died, Each Before Age 50

May 2, 2012

Matt Gee always says that “Junior does what Junior wants,” and what Junior Seau wants on this day is to die. Matt is out for breakfast when he gets the news, in the staccato notes of a breaking national story: Junior Seau . . . dead . . . gunshot wound to the chest . . . possible suicide.

Matt is shocked. At 42, he is not yet used to watching his teammates die.

Junior was a Samoan from San Diego. Matt was a country boy from Kansas. They became friends only because they were both USC linebackers. Matt was the one who gave Junior the nickname June Bug, after the beetles that invade Kansas summers. Junior didn’t even know what a june bug was.

Junior was the best player on their USC teams—such an absurd amalgamation of speed, strength and agility that it really did seem like he could do whatever he wanted. He often ignored his assignment but tackled the ballcarrier anyway. Matt joked that Junior got this otherworldly athleticism from eating so much pineapple. Once, the two went swimming in the Pacific, and Junior swam up to a dolphin and grabbed its fin.

Matt became a successful businessman, happily married to his college sweetheart, raising three kids, proud of what his USC career begat. Junior became a Pro Football Hall of Famer—such an enormous star over 19 NFL seasons that most of his old teammates rarely saw him. Only later would they see these fleeting interactions as dots marking his descent: Junior squaring off against offensive tackle Matt Willig, a fellow Trojan, in an NFL game in 1994 and failing to recognize him . . . Junior stopping to say hi to another USC teammate, Calvin Holmes, at a restaurant in 2002—but “walking like a zombie,” Holmes would say. “I’m thinking, Wow, football messed you up like that. It was just his soul. His brain.” (Seau would play pro football for seven more years.) . . . Junior, who didn’t drink in college, slurring his way through a speech at a golf tournament he was hosting—“a sad, depressing kind of drunk,” says former USC defensive back Mike Salmon, who was so saddened and depressed by the scene that he walked out.

Junior Seau . . . definite suicide . . . 43 years old.

Matt drives home from Eggs ‘N’ Things in Simi Valley, Calif., with tears in his eyes. They will not be the last.

***

Twelve names. Twelve dreams.

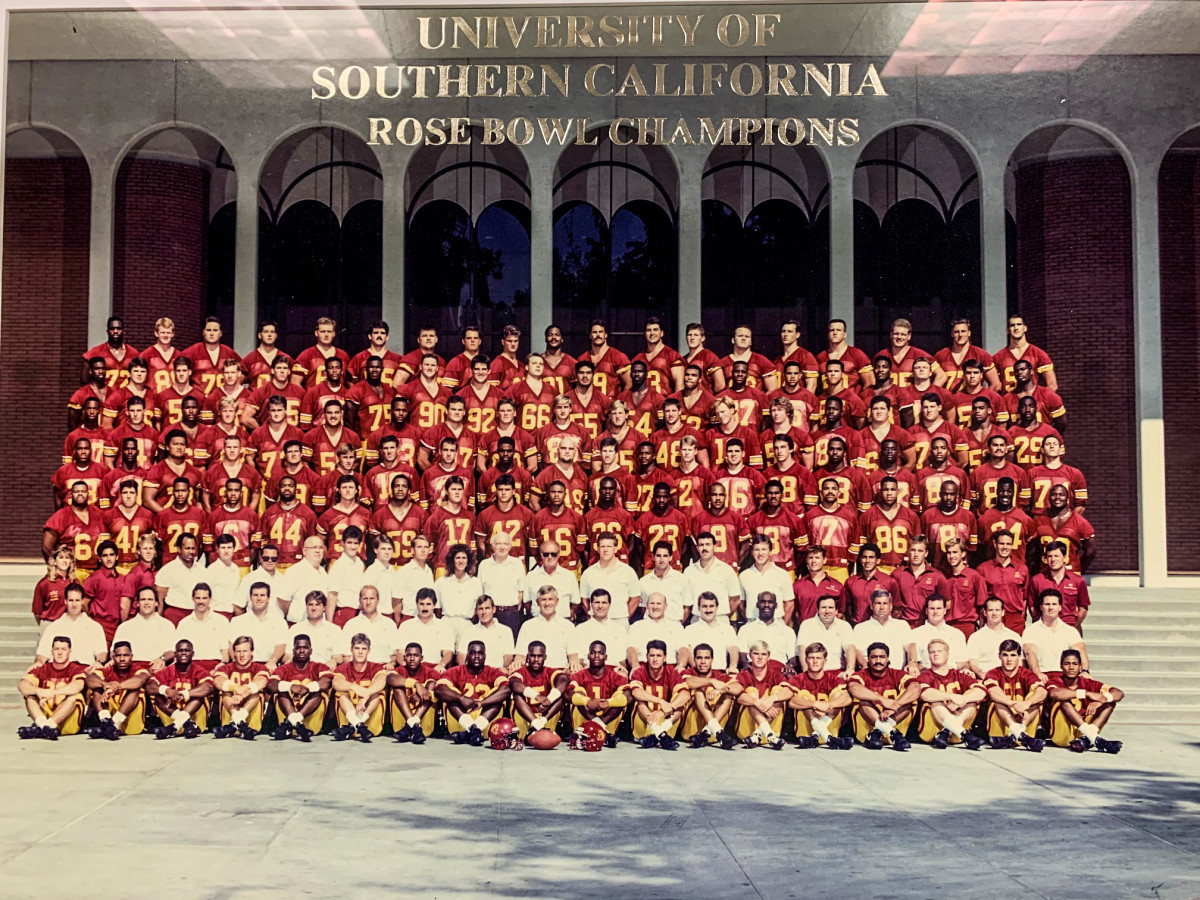

Twelve linebackers on the Trojans’ depth chart in the fall of 1989, each with the strength of a man and the exuberance of a boy, swimming in everything USC has to offer: joy and higher education and adulation, endless adrenaline surges, alcohol, cocaine if they want it, steroids if they need them. Anything to feel fearless and reckless, wild and free.

Twelve players, all trying to impress men like linebackers coach Tom (Rogge) Roggeman, who served as a Marine in Korea. In 1989, tacklers are taught to lead with their heads. Drug tests are easy to beat. Pain is for the weak. Complaints are for the weaker. This is how the game is played.

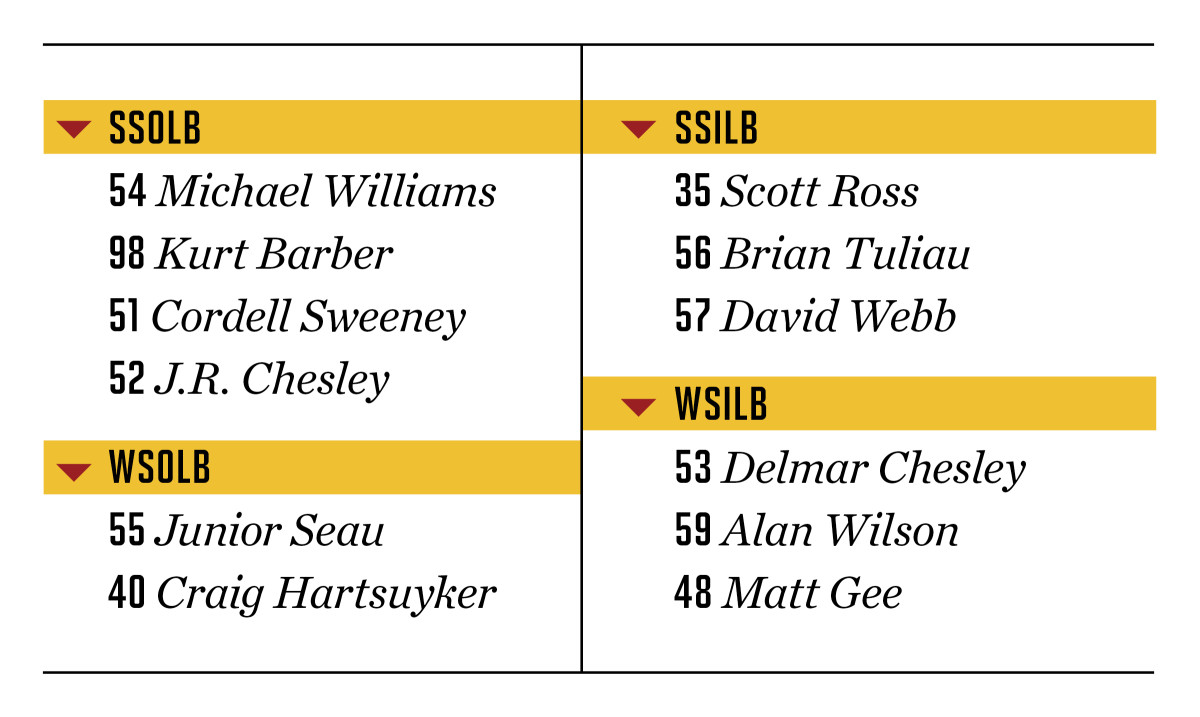

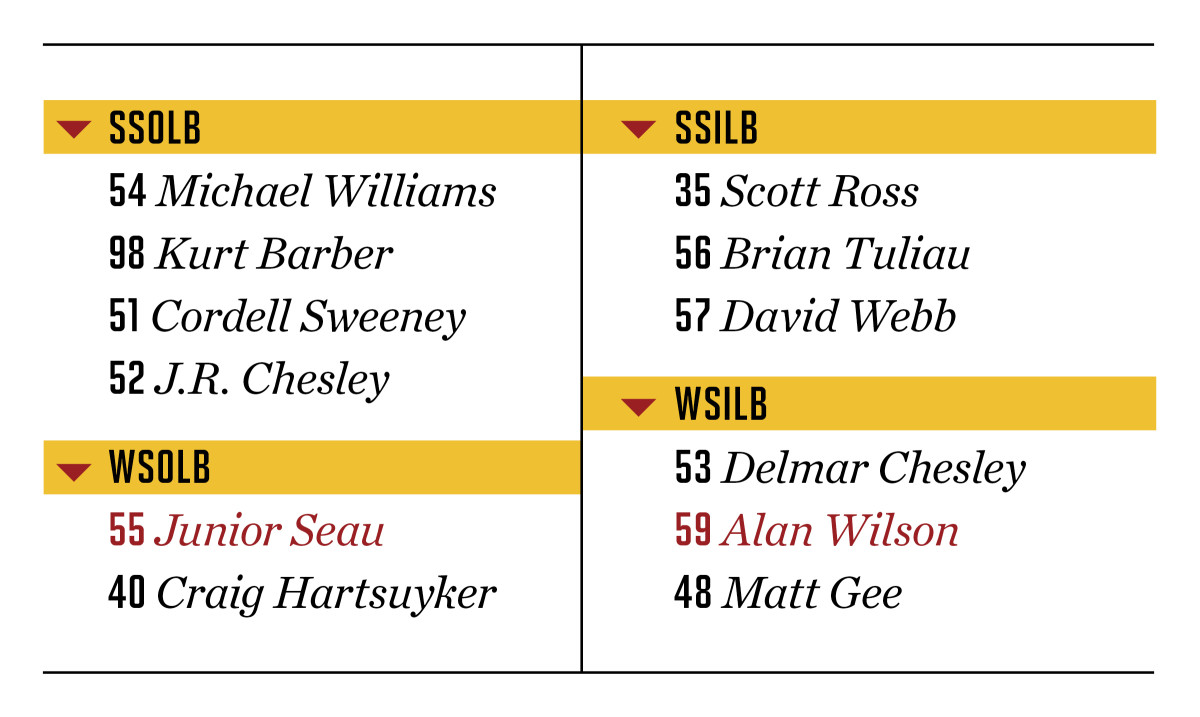

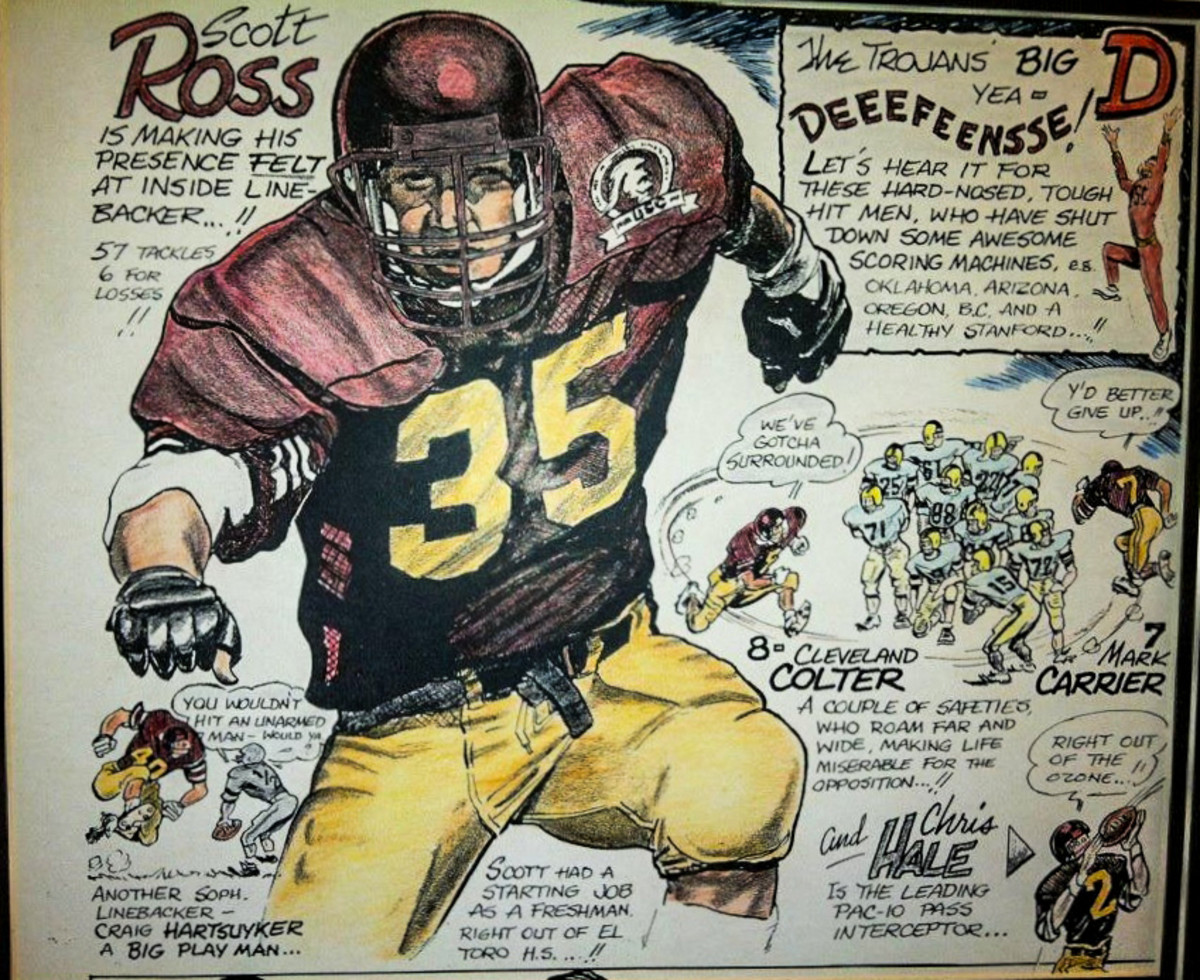

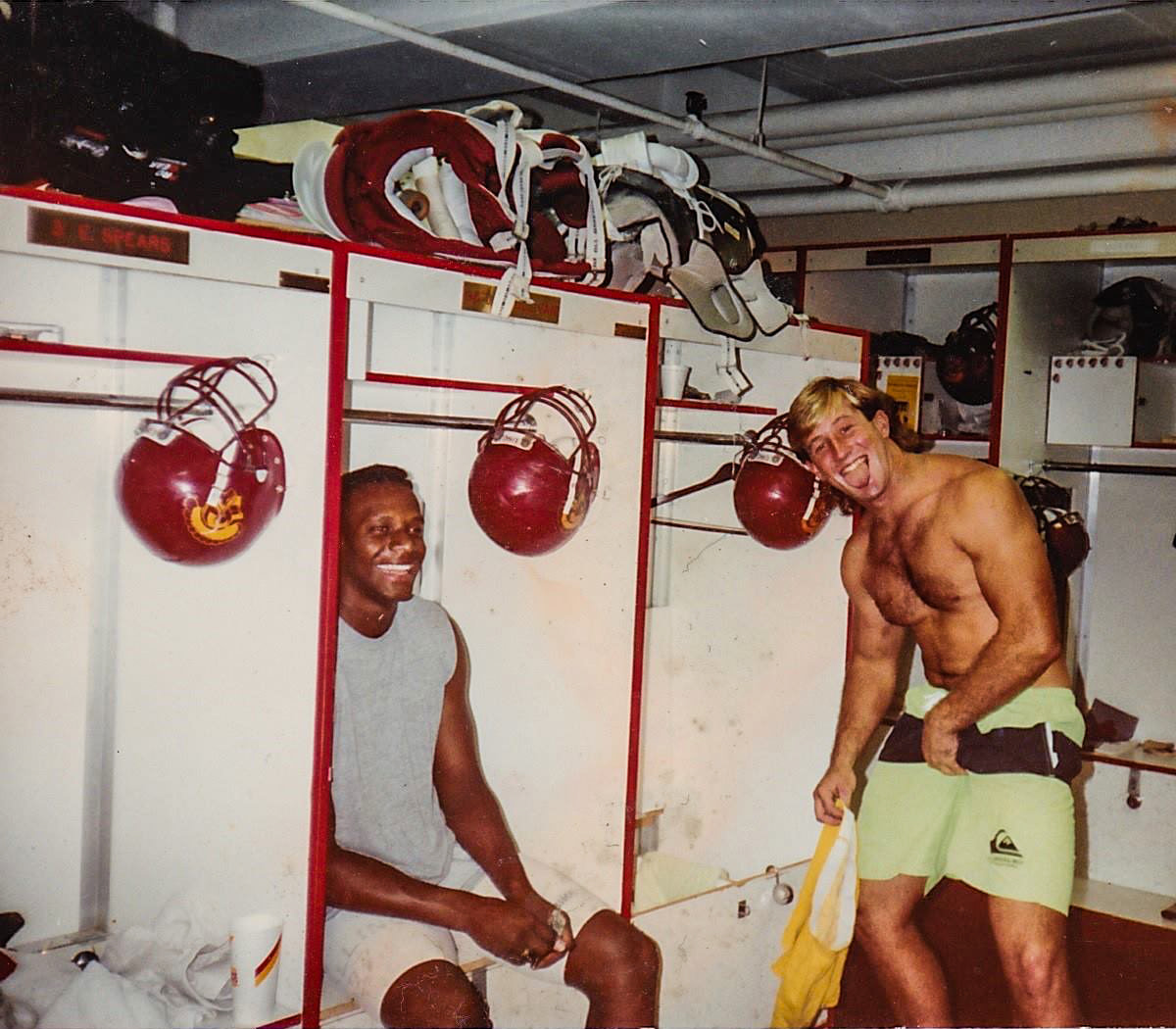

The linebackers form a team within a team, each player with his own role. Seau is the most talented. Alan Wilson is the quietest. Craig Hartsuyker is the heady technician. Scott Ross and Delmar Chesley serve as mentors to Matt, who will become a starter after they leave. David Webb is the team’s resident surfer dude.

The Trojans go 9-2-1 and then win the Rose Bowl that season, but football fools them. The linebackers think they are paying the game’s price in real time. Michael Williams takes a shot to the head tackling a running back in one game and he is slow to get up, but he stays on the field, even as his brain fogs up for the next few plays. Chesley collides with a teammate and feels the L.A. Coliseum spinning around him; he tries to stay in but falls to a knee and gets pulled. Ross, who says he would run through a brick wall for Rogge, breaks a hand and keeps playing. After several games he meets his parents outside the home locker room and can’t remember whether his team won or lost. Hartsuyker breaks a foot and stays on the field. Another time, he gets concussed on a kickoff, tells trainers he is fine, finishes the game and later shows up on fraternity row with no recollection of playing that day. Somebody sets him on the floor in front of a television, like a toddler.

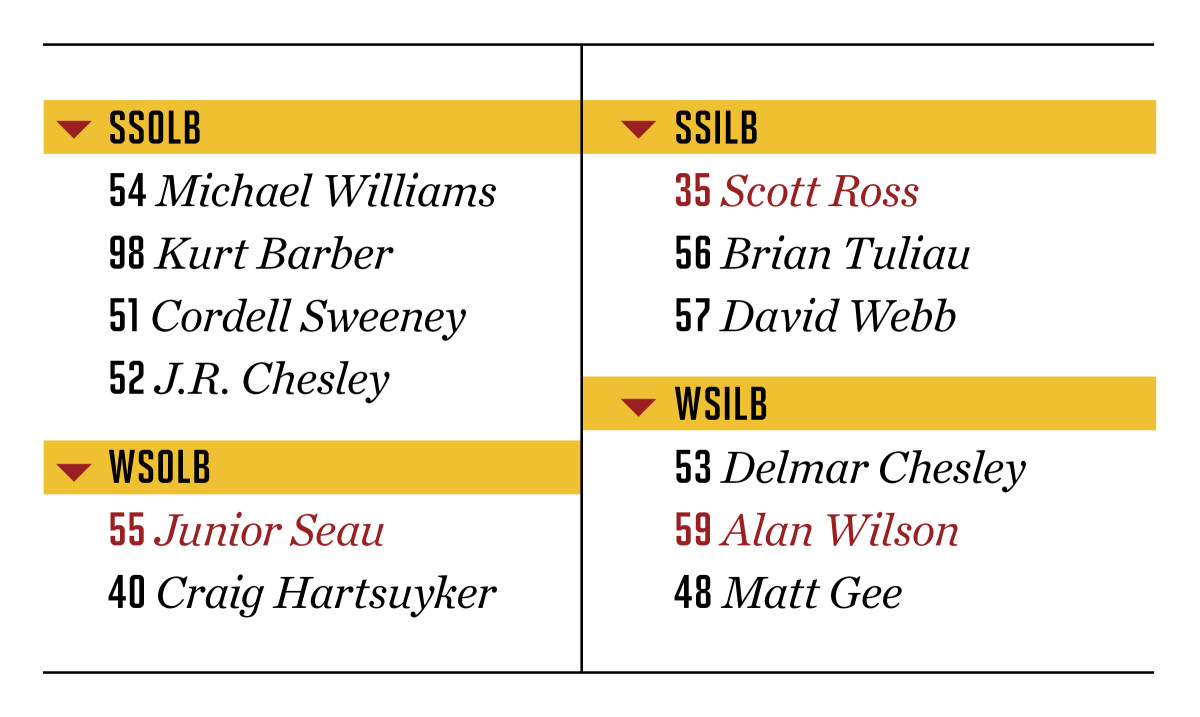

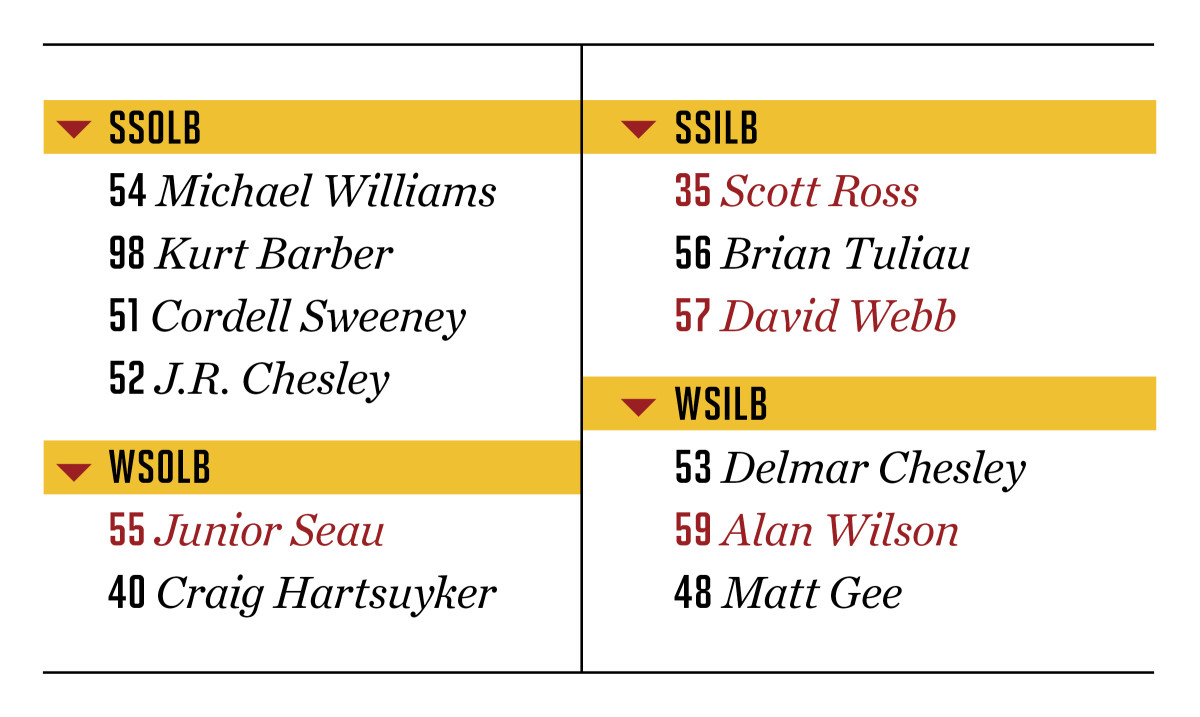

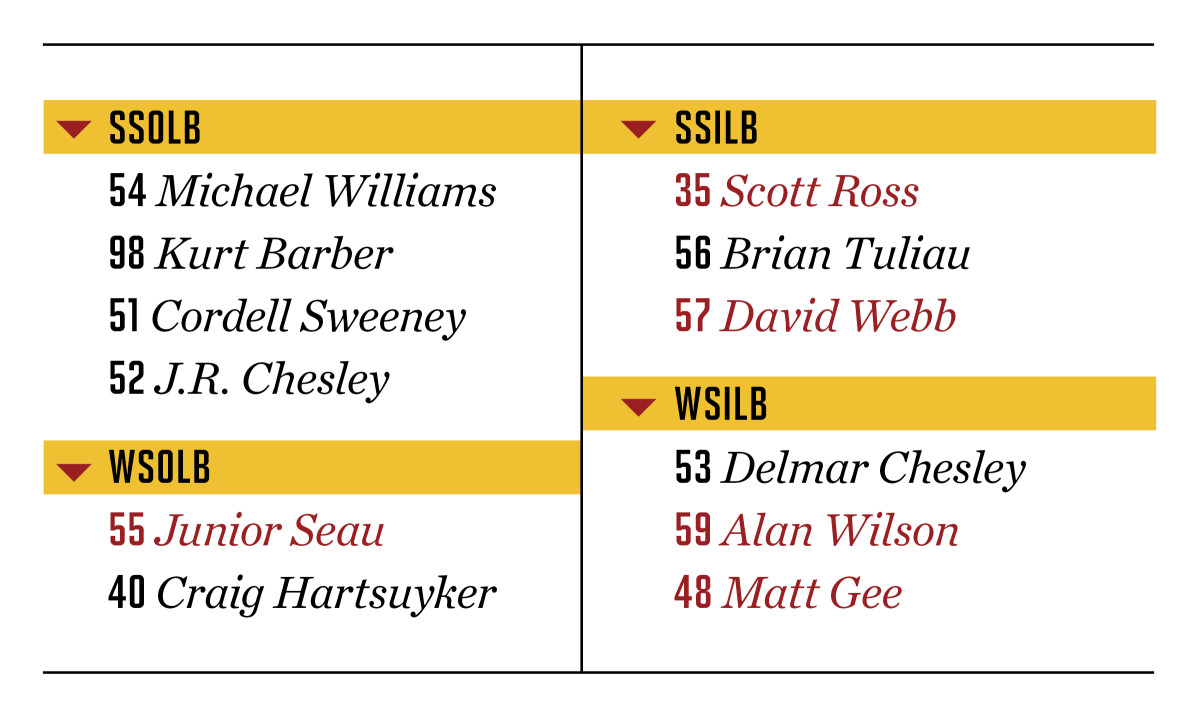

In one game Brian Tuliau gets a painkiller injection in his ankle, returns for a couple of plays and comes off. He barely thinks, though, about his concussions, which number at least a half-dozen. He is surely concussed before one game even begins; having just lost his starting job, he takes out his anger on everybody in practice, steadily damaging his brain as Saturday approaches. Nothing stings quite like dropping on the depth chart, which looks at the beginning of the 1989 season like this:

Twelve college students. Five will die by age 50, their lives stamped forever with an early expiration date.

***

May 14, 2002

The quiet one goes first and goes quietly. Alan Wilson is not close to Matt, but he is not that close to anybody. A-Dub did not attend parties or play practical jokes on teammates; he conversed but rarely started conversations. Calvin Holmes, who also played at Carson (Calif.) High with Wilson, says, “He was up underneath a rock. He was a hermit.”

The Trojans saw Alan every day but didn’t really know him well, and so he makes a smooth transition from man to memory. Players remember that he was one of the hardest hitters. That his white undershirts were old and discolored. What those Trojans did not see: Alan’s laughing with his family, or taking his kid brothers to Lakers and Dodgers games, or buying flowers for his mom every year on Mother’s Day. After their playing days ended and they all dispersed, most never saw Alan again.

They do not see him become depressed and balloon to 100 pounds over his playing weight. They do not know he has diabetes and hypertrophic heart disease. Alan’s brother Robert visits his apartment regularly, and he sees A-Dub alone, surrounded by cookies and doughnuts and ice cream.

On May 13, 2002, Robert finds his brother in bed, physically able to rise but unwilling to. Alan does something Alan never used to do: He cusses out his kid brother and tells him to go home. Robert calls their mom.

Call an ambulance, she tells Robert.

Don’t call an ambulance, Alan tells Robert.

Alan promises he will get up and take a shower. He turns on the water, and Robert leaves for his janitorial job.

The next day, Mother’s Day, Alan does not call his mom or send her flowers, and so his father goes to check on him. A-Dub is in bed, dead. The shower is still running.

The Trojans never hear that Alan’s mental health had declined. They hear only that he died of diabetes. A decade passes, and then Junior puts that gun to his chest, and among the linebackers, that’s two dead.

***

September 21, 2014

Even among the boys at USC, Scott Ross was a wild one. He was not nearly as gifted as Junior, but he too was an All-America, a missile seeking contact and reveling in it. It was common to see him get in fights at parties and unusual to see him lose.

Scott scared people, but he did not scare Matt. Matt knew him too well, loved him too much.

They met on their recruiting weekend at USC and became fast friends, later sneaking out of their team hotel on the eve of the 1990 Kickoff Classic so they could see New York City. Rogge swore he saw them returning, but either he couldn’t prove they’d left or he decided to let it slide. Instead, he said, “You guys were lucky.”

A decade later Matt is still lucky. He has figured out how to be both a responsible adult and a goofy kid. He works all day building up his insurance business, but he also loves blowing up Pepsi bottles in his backyard.

Scott is not so lucky. He blows up his life. Scott plays briefly with the Saints, a rookie with a veteran’s battered body, already in steep decline. By his mid-20s he has a degenerative disk in his back, a hip that rubs bone on bone, a thumb that bends backward and a wrist that pops out at an awkward angle—but none of those is the real problem. He started tackling people hard when he was eight. People ask how many concussions he’s had, and he says he remembers 12.

Scott was a good husband, once. A good dad. He bought groceries and grilled dinner and played with his son (Zachary, from one marriage) and daughter (Caroline, from a second). His second wife was named Marla but he called her “Princess,” and he treated her like one. He was a successful salesman, first for Hilti and then for 3M, flashing his charm and his Rose Bowl ring to close deals. He ran the Houston Marathon.

But football catches him from behind. In his 30s, Scott turns tormented, panicky and depressed. He drinks as if he’s defending a two-minute drill—intensely, desperately.

If alcoholism makes life a blur, this is the blur of Scott’s life: He gets drunk, flips a company van and is reassigned to a desk job. One Halloween he drives drunk again, hits another car, flees and then takes his daughter trick-or-treating. He puts a fist through one of Marla’s favorite paintings, throws a candle across the kitchen and pushes Marla. He says he tried to kill himself in a bathtub. More than once, Marla calls his parents, Janie and Marshall, crying, and they aren’t sure what to believe, but eventually they believe it all. Marla bails when Scott gives her a black eye. From there, Scott declines.

Marla changes the locks, then sells their house in Montgomery, Texas. She and Scott share custody of their daughter, but one time Marla goes to pick up Caroline and nobody answers the door. Finally, Marla hears Caroline calling: “Momma, I can’t wake up Daddy.” Scott is passed out drunk.

Marla takes Caroline home to Louisiana. Back in Texas, Scott rents a little house on a lake, then moves into a friend’s trailer. One day Scott calls Jeff Peace, who played defensive line on that 1989 USC team; Scott is crying, and he says he’s pointing a gun at his mouth.

Peace does what teammates and brothers do. He tells Scott to come to California and live with him, with one condition: no drinking. Scott goes. But he drinks, and Peace kicks him out. If this were an arcade game from his childhood, Scott would be down to his last few quarters.

He uses one to call Matt Gee. Matt sets Scott up with an apartment in Ventura . . . and the cycle repeats. Scott gets nuclear drunk, runs naked in the streets, trashes the place and gets kicked out of there, too.

Sometimes Scott sleeps on a friend’s couch, and sometimes he sleeps on the streets. He discovers how easy it is to buy Oxycontin. Nobody can figure out how to help him. And still, in a life with so few constants he has Matt, there in his past, there in his present, there to answer the phone.

Hey, Matt! Say hi to my girlfriend, Laura!

Laura Lee Fitzgerald will never be able to fully explain why she takes Scott into her home in Paso Robles, Calif. Love is a woefully insufficient answer. Their life together is a slapstick comedy soaked in alcohol and drenched in blood.

Scott makes pictures for Laura with sparkle paint—but he also steals her maroon Jeep Cherokee. He stabs himself in the leg in the bathtub. He gets into a fight with some teenagers at a Taco Bell. He smacks a Lenox candy dish over his head, spurting blood all over the walls like a lawn sprinkler.

He stops his car, inexplicably, in the middle of an intersection and Laura, in the passenger seat, screams, “Scott, what are you doing?!”

“What?” Scott asks.

“You’re going to kill us!”

“Ohhh,” he says calmly, in a voice you might use if you forgot to buy orange juice at the grocery store, and he hits the gas again.

He carries around a Saint Christopher pendant and a dirty rabbit’s foot, for “protection.” He breaks double-pane windows in Laura’s house. He speaks proudly of his glory days at USC, about Matt and the boys, but he gives away his Rose Bowl ring to his dentist. After one episode of public drunkenness, he tries to flee police on a tractor, wearing only his boxer shorts.

When finally Laura kicks him out, he stands outside, screaming, “Laura! I love you! Let me in!” loud enough for the whole neighborhood to hear.

He steals Laura’s credit card to buy liquor. He pins her against a wall and starts choking her. Confronted with his drunken sins, he says, “I never did that,” and he seems to believe it.

He sells his trophies so he can buy Laura an engagement ring, and he writes her a letter in puffy paint: Laura, my angel, marry me.

Laura knows better than to marry Scott, but she has a hard time ditching him. The Scott she sees every day is frightening, but the Scott she knows is somewhere inside him—her sweet Scott—and she can’t let that go.

Scott drinks like it might kill him, like he wants it to kill him. Jägermeister, beer, rubbing alcohol, Listerine—what’s the difference? He tries rehab but it never lasts. He goes to a halfway house, hates it and drinks rat poison, which gets him sent to a hospital. When Laura finds him in a hotel, surrounded by bottles of pills, she finally tells him it’s over.

In 2011, Scott moves to Houston to live with Janie and Marshall, and Marshall retires early to take care of his son. A doctor diagnoses Scott as bipolar, with frontal-lobe dementia—an offshoot, he strongly suspects, of the pounding Scott’s brain took playing football. Nobody could foresee that in 1989.

Scott is now like a little kid, grateful to live with his parents, telling them all the time that he loves them. But his brain’s decay is irreversible. A good night’s sleep becomes an impossible dream. He puts blackout shades in his bedroom, but they block only the light. They cannot push out the darkness.

“I can’t take this! Make it stop!” Scott screams at his parents. “When I close my eyes, it all comes back and the demons won’t shut up.”

The demons: They are what stand between the person he wants to be and the person he has become. The demons are the only companions he doesn’t abuse. When Scott gets drunk, he gets violent. But when he doesn’t get drunk, the demons move in closer. He cannot win.

Scott tries to hang himself in the attic. He grabs his mother by the arms and screams, “It’s all your fault! You did this to me!” And then: “Why did you let me play football?”

There is no good answer. Scott Ross was as much a football player—mentally and physically—as anybody you could meet. Now he is as much of an ex-football player as anybody could fear becoming.

He puts his mother in a headlock, and a doctor tells his parents they have to kick him out. The doctor also warns: “Be prepared. Scott will be either dead or in prison within a year.”

Scott returns to Louisiana, to be a father to Caroline again, but she’s a teenager with her own life, and he has an addiction with no life of his own. One Sunday, he takes Caroline to get doughnuts. The shop is closed and Scott tries to break in, screaming, “I want doughnuts! I want doughnuts!” He has the strength of a man, the exuberance of a boy and the brain of a troubled and lost soul.

When a police officer opens the side gate at Marshall and Janie’s house and finds them in the backyard, Marshall is prepared for what’s coming. Before the officer speaks, Marshall asks: “What has Scott done now?”

Scott has died, that’s what he’s done.

Nobody is surprised. Matt wishes he could have saved his friend, but nobody could have saved him. Matt wonders whether Scott killed himself. Scott did kill himself, whether he meant to or not. He abused his body until it was functionless, and then he left it slumped over in the driver’s seat of his pickup truck, in a church parking lot. The official cause of death is heart failure. Well, it has to be something. Marla believes Scott drove to the church hoping somebody would help him and then drank himself to death.

Matt wants to speak at Scott’s funeral, to carry Scott’s casket, to take the last steps of a friendship that began in high school. But he can’t. On the day of the service, Matt is in the hospital for a medical procedure of his own, so some USC teammates come by and shoot a video.

“Scott Ross . . . was an asshole,” Matt says into a camera, a line that gets laughs only because it is said out of love, by a longtime pal. Matt finishes his video, and his friends leave the hospital room. He hears his wife, Alana, say, “I’m so sorry,” and he sobs.

***

April 22, 2017

Los Angeles is a single city when you don’t live there, and a hundred cities when you do. Try driving the 80 miles from Simi Valley to Orange County when there’s traffic (and there is almost always traffic). It’s at least two hours, either direction. Matt doesn’t care. By the beginning of 2017, he’s making that drive every week to visit David Webb.

College did this: It introduced Matt Gee, the Kansas country boy, to David Webb, the surfer from Irvine, and let the friendship jell. They were freshman roommates.

David grew a nasty-looking goatee, wore huge globs of eye black during games, crushed teammates in the weight room, instigated fights at practice and told the Los Angeles Times, “I have good technique, but I prefer to run over ’em.” Off the field, though, David was chill. Anybody looking for him was wise to start at the beach.

After college David finds work as a longshoreman, and Matt smiles at the fit: “A great job for him.” David’s first wife, Casey, dies of breast cancer, and for a while he keeps to himself, raising their boys, Luke and Joshua. Matt figures David is fine, just kind of out of touch, because David is never out of control as Scott Ross was. David is always fine.

David is not fine. He frequently loses track of his thoughts and stops talking midsentence. He remembers birthdays but forgets words. Family members learn to pick up the pieces of conversations for him, so he doesn’t get embarrassed. His fuse gets shorter. He yells at his sons for minor transgressions. He shows up late a lot. He drinks too much. His new girlfriend, Leslie, comes home from work, ready to go out for the dinner they’d planned, but David and his boys are still in pajamas. He has no idea what time of day it is.

David’s father, Charlie, thinks he is “punch drunk.” His mother, Carolyn, says he is “regressing.” His brother, Greg, sees David every week, and he can tell something is wrong—seriously wrong, like early-Alzheimer’s wrong. But Greg does not know what to say. How do you tell your brother his brain is failing? Greg thinks David will have “an early run in life.”

David develops lesions on his face, especially around his ears, from too many hours in the sun, for too many years, and his family pushes him to see a doctor. He doesn’t have health insurance, though, and he tells them not to worry about it. Please, his parents beg. We’ll pay for it. But he still won’t go. They fear that if they push him too much, he might snap, maybe cut off the relationship entirely.

David finally sees a doctor and is diagnosed with squamous cell carcinoma, which is highly curable. Usually. But he has waited too long. The cancer has spread, and he is dying.

Matt has already learned about Junior’s death over breakfast, on the news; Alan’s by word of mouth; and Scott’s on a phone call. He is not going to let David die without him.

Matt takes David to various doctors. Maybe he has been misdiagnosed; maybe he’s not getting the right medical care. A fixer by nature, Matt is in denial. Finally, he comes to understand: The best he can do is just be there.

Gosh, wasn’t it just yesterday that they were college kids hanging at David’s house, sitting in his family’s hot tub all day, getting up only to grab a hot dog or go to the bathroom? They’re down to days now. Hours. Minutes. David’s short-term memory is mush, but his long-term memory is still there, and they laugh like old times. Matt tells David’s sons about noodling for catfish back in Kansas and on one visit brings along a cowboy boot that belonged to David in college. Matt had swiped it as a gag, years ago, and he has kept it all this time as a souvenir of their friendship.

Matt buys cards that David can prepare for the boys on their 18th birthdays, on their high school graduation days, on their wedding days—all the milestones he will clearly miss. David signs the cards: XO 44.

Cancer deforms David’s face. Matt shows pictures of David to friends who should recognize David, but they don’t. Eventually, David can’t even speak. He has a whiteboard, though, and on it he writes to Matt:

I love you

Thank you

Please watch my kids

Matt offers to adopt Luke and Joshua, but Alana is uneasy about it. They have three kids of their own. David and Leslie decide instead that Leslie will raise the boys. They marry as he is dying, and they throw a big party so friends can say hello to David. Hello and goodbye. In David’s last days, Leslie removes a bandage from his ear. The ear falls into her hand.

Leslie will always wonder whether the damage that football did to David’s brain made him more vulnerable when the cancer came. His parents and his brothers believe the connection is clear but indirect: If David’s brain had functioned properly, if he had it all together, he would have seen a doctor earlier, and he would probably be alive.

Matt does not know all this. He just knows that he loved David when he was 20, loved him when he was 47, and he will not see him reach 48.

***

December 31, 2018

As an attorney for Farmers Insurance, Craig Hartsuyker studies mortality rates as part of his job these days, and he knows an outlier when he sees one. He tells his wife, Marlo: “That’s a lot of linebackers.”

Four out of 12. The mind reels. If a man wanted to live to 50, he was better off sharing a foxhole with Tom Roggeman in Korea than he was playing linebacker for USC in 1989.

Some of those Trojans wonder, to themselves and to one another: Who is next? Hartsuyker? He suffered concussions in college, but he feels good. Brian Tuliau? He gets a massage twice a month to combat lingering back and neck problems, but he is faring well, too.

Michael Williams works in the Dallas regional office of the U.S. Department of Education, and he needs to write down his daily tasks so he doesn’t forget them. But he believes this is a product of age, not of football. He feels good.

One of Cordell Sweeney’s friends asks him, after Junior’s death: “Did you ever think that having your right knee reconstructed was a good thing?” Maybe it kept him from playing too long. He is an executive with a sporting goods company in Orange County, seemingly healthy and happy. He has completed three full Ironman triathlons and six half-Ironmans. He is an unlikely candidate to go next.

Kurt Barber survived 50 NFL games as a human pinball; then he went into coaching, eventually taking a job at his old high school, in Kentucky. He quit after one year to sell insurance, but he stays in touch with a few old USC teammates. J.R. Chesley missed his last college season with shoulder injuries; now he works for State Farm insurance in Washington, D.C., and he feels sharp.

J.R.’s cousin, fellow Trojans linebacker Delmar Chesley, sees four position mates drop dead, and the thing that gnaws at him starts to make him angry: The linebackers hit too much. They were expected to tolerate too much pain. Not all of the old Trojans feel this way, but Delmar felt it back at school. He feels it even more now.

Delmar has had shoulder, back and hip-replacement surgeries. He also finds himself more easily agitated as he ages. He was ahead of Matt Gee on the depth chart in 1989, but he and Scott Ross helped groom Matt for a starting job. If Matt knew Delmar was struggling, maybe he could repay him all these years later. Delmar, though, doesn’t appear to be struggling. He has a steady job in pharmaceutical marketing, in D.C. He says his memory is intact.

With four linebackers gone, and the remaining scattered across the country, Matt continues running a commercial insurance firm, but he is thinking about changing careers. Outwardly, he seems like the same old amiable boy from Kansas: quietly generous, eager to help friends, enjoying the life he built with Alana.

He is a master at hiding the dots that mark his descent.

Even his own wife misses them at first. One Sunday, with an NFL game on TV and a beer in his hand, Matt says, “Alana, I feel like everyone’s out to get us.” He tells her he feels “funky.” It is an odd moment, but he doesn’t say anything like that again for at least another year.

When Matt starts to feel down again, he combats it by staying busy, trying to distract himself. But still he feels funky. He starts arguing more with Alana. He drives faster when the streets are clear and gets road rage when they aren’t. He barks, “Why is nobody taking out the trash?” instead of taking it out himself.

One day Matt falls in the kitchen and hits his head, and a friend tells Alana what she has not let herself see: “He’s a f------ alcoholic.”

Alana, who says her mother struggled with drinking, does not keep liquor in her home. Matt has been hiding it, coaching his kids’ sports teams in the afternoon and then slamming vodka with friends. He does not slur words, and he rarely stumbles, but now Alana is on to him, and she confronts him. “Are you drinking?”

Matt lies: “No.”

Meanwhile, his body starts failing. He gets ascites, an accumulation of fluid that causes abdominal swelling. He has a congenital vascular disorder called Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome, which at birth left him with a port-wine stain along the left side of his body, and this only exacerbates his growing medical problems.

Alana catches Matt drinking vodka out of a Gatorade bottle at the hospital, and she is furious. The Gees have plenty of money, the lube in America’s health care system, and Alana persuades Matt to spend $60,000 on a one-month rehab stint in Malibu. But it doesn’t take.

Matt gains weight. He struggles to go up and down stairs. Sometimes Alana wakes up in the dark and finds him standing over her, yelling, because he called her phone from the other room and she didn’t answer.

He starts buying knives on Amazon for no clear reason. One day, Alana finds Matt holding his brother Mitch’s hunting shotgun, which had sat in their garage for years. She asks what he’s doing, and he tells her, “I was going to send that back to Mitch.” She doesn’t believe him. There’s no ammunition in the gun, but she hides it anyway.

She wonders why her husband is being such a jerk. If he would just sober up.

He goes to a treatment facility in Pasadena, comes home, relapses, goes to a detox center and works with a doctor—another former USC alum—and comes home again. Alana hires a sober life coach to be with Matt, take him to meetings, get him back on track.

Eventually, though, Alana starts to realize the alcoholism is hiding something larger. They used to finish each other’s sentences, but now, in the middle of routine conversations, Matt puts both his hands in the air, palms up, as if Alana is speaking a foreign language.

They go to therapy together. Alana kicks Matt out of the house, but she can’t be apart from him for long; she believes that if she divorces him, he’ll kill himself. She would rather die first. She loves him that much. She just can’t find him anymore. Sometimes Matt says, “I’m not O.K. . . . I’m not O.K.,” and Alana asks, “What do you mean?” He cannot explain it.

His good is worth it, she tells the kids. His good is worth it, she tells herself. She cries every day.

Matt goes from beloved dad to another person Alana needs to manage. He picks up Tanner from a high school lacrosse game, then pushes his son up against a car and scolds him: “I can’t believe you were drinking!” When Alana asks what happened, though, Tanner says, “Mom, he picked me up drunk.”

Matt feels guilty. He sheds the basics of self-care, gorging on meat and potatoes; downing a Wendy’s double cheeseburger, chicken sandwich, chili and fries in one sitting, eating like he wants to get fat. His face is swollen and discolored. He spends so much time at the hospital that his medical records grow into an impenetrable stack. He gets his stomach drained, he has a Denver shunt put in his arteries, he has sleep apnea, he is obese.

His stomach grows distended. He gets neuropathy in his feet. At one point, he asks a doctor: “Please, can you cut my foot off? I don’t care. I can’t live with this pain anymore.” Alana can’t take it.

In one year, Matt spends 152 days in the hospital. Close friends know he is having health problems, but they don’t see the root of them. He has been prideful for so long, solving problems himself and keeping conversations light, that he knows no other way. He has spent a lifetime as a helper; he does not know how to be helped. He regularly calls a childhood friend, Corey Yeager, at 4 a.m., just to chat. He’s struggling to find the will to live, yet he still tells people, “Everything’s cool, man.”

At Christmastime in 2018, Matt sits with Yeager at his pool in Simi Valley. They were teammates when Matt started lighting people up in sixth grade—that’s what they called it: lighting people up. Corey had watched as high school opponents steered their offenses away from Matt, they were so scared of him; watched Matt move to middle linebacker, where nobody could hide. Matt played fullback, too—every snap, on both sides of the ball. It all brought him joy and friendships and a scholarship to USC and a happy marriage and a successful career and three wonderful kids . . . and now it has led him to look at his childhood friend and say it, the worst sentence in football: “Maybe I’m dealing with this CTE.”

A week later, Alana takes Tanner to Park City, Utah, because she has promised him for two years that she would take him skiing, and Matt seems like he is on an upswing. He has been sober, he has recently recovered from an infection, and Alana thinks it is O.K. to spend a couple of nights outside her house for the first time in years. Then her daughter, Malia, calls and says Dad isn’t acting right. Alana FaceTimes Matt and says she will be home soon, but on the day she plans to return, on New Year’s Eve, she gets another call. Matt Gee is dead.

And that’s five. Five linebackers out of 12.

***

In January 2020, Alana Gee sits at Eggs ‘N’ Things in Simi Valley, at the same table where she and Matt were sitting eight years earlier when they found out about Junior Seau. By now, the U.S. has learned about head trauma and football. Friends wonder whether Matt killed himself, like Junior did. They are too polite to ask.

The short answer is that, no, Matt did not kill himself. The longer answer is that a coroner found three times the legal limit of alcohol in Matt’s blood; he also suffered from hypertension, ascites, cardiovascular disease, anomalous small coronary arteries, complications of hepatic cirrhosis and obstructive sleep apnea. When he died, he had

paperwork on his desk for a concussion lawsuit against the NCAA.

Alana does not need the money, but she does need an answer to the final question of her husband’s life: Did he choose to become a different person, or did his brain rebel against him?

In March, the Boston University School of Medicine sends Alana its report on Matt:

Chronic traumatic encephalopathy: Stage II/IV

Overall, his low stage CTE is consistent with his history of repetitive head impacts through football play. Both CTE and his multiple infarcts likely contributed to his mood, behavioral and cognitive dysfunction.

Alana wishes she’d known this when Matt was alive. She wishes she could have treated him from the beginning as a patient with a medical problem, instead of as a husband with an attitude problem.

Does she wish he had never played football? There is no simple answer.

It would be easy to say the game was a mistake—for Matt, for David, for Scott, for Alan, even for Junior. Without football, Matt might be alive. But without football, he would not have met Alana, would not have had three kids, would not have built lifelong friendships, would not have enjoyed most of what made his life so great. The bridge from age 20 to age 50 looks a lot shorter after you cross it.

Besides, Matt loved football. They all did. So many of them were wild boys; maybe the game killed them, but maybe it domesticated them first. They packed a lifetime of memories into their college years. At USC, Matt once turned down a dinner invitation to the house of former President Ronald Reagan because he didn’t want to miss an evening’s worth of fun with his buddies. Alana thought that was ridiculous, but she also kind of loved it.

“This is how they rolled,” she says. “You’re living a life most men would die for.”

In a dream home, in America’s paradise, Alana Gee tells herself that her husband lived a great life, not just half of one.