The Rise of the Bellarmine Knights: How a Hometown Hero Built a Division I Basketball Program

LOUISVILLE, Ky. — The Miller Transportation bus was idling in the parking lot at noon Thursday as Scotty Davenport reached into his car and stuffed things into an already-full duffle bag. A couple shirts were squeezed in. A belt went in the side compartment.

The journey of a coaching lifetime was about to begin.

“Think of all the years in that gym,” Davenport says, cocking his head toward Knights Hall a few feet away. “Think of all the hours—around the clock sometimes, literally. And think of where we’re going now.”

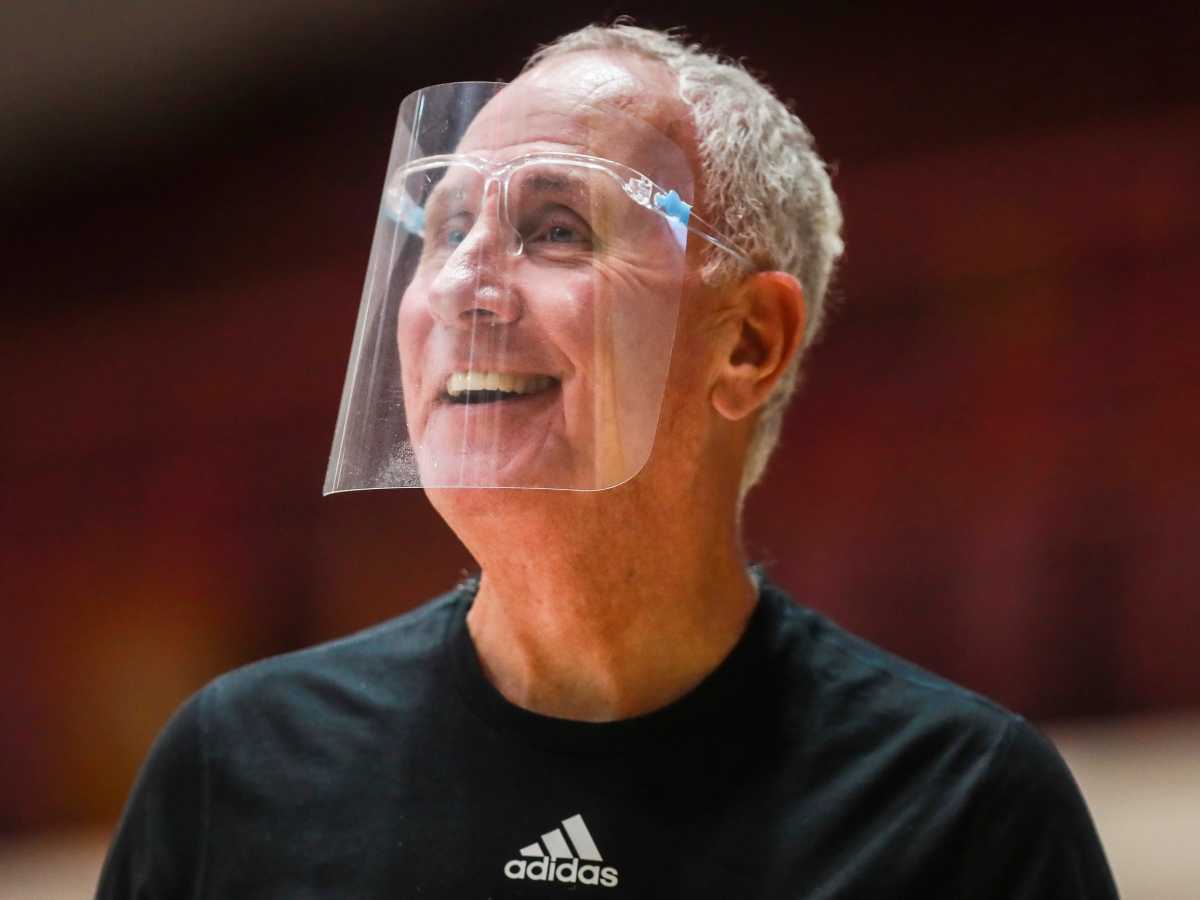

Davenport paused, blue eyes sparkling above his maroon mask. “It can be done,” he says. “It can.”

Where the Bellarmine University Knights are going now is Cameron Indoor Stadium. Their first game as an NCAA Division I basketball program will be Friday night against none other than the Duke Blue Devils. After decades at the Division II level playing in nondescript, Great Lakes Valley Conference gyms around the Midwest, the DI baptism will come in the game’s cathedral.

Bellarmine is one of four 2020 additions to D-I, alongside Tarleton State, UC San Diego and Dixie State. That swells the ranks to 357. But only one of the newcomers is opening like this, finding an opponent suitably grand to match the ambition that got Bellarmine here.

The school is new to Division I, but Davenport is not—he was an assistant to Hall of Famers Denny Crum and Rick Pitino at Louisville before getting the Bellarmine head-coaching job in 2005. Davenport put his connections to work when constructing the team’s original schedule.

In July, the opener was going to be on different sacred ground in the sport: UCLA’s Pauley Pavilion. Davenport arranged that through Bruins coach Mick Cronin, who also was on Pitino’s staff at Louisville in the early 2000s. The second game was Duke, a matchup that came to be with the help of assistant coach Nolan Smith—his late father, Derek, was a standout for Louisville when Davenport was a walk-on junior varsity player in the early 1980s. A trip to Gonzaga also was on the slate.

But as everyone in college hoops knows, summer schedules became as disposable as cocktail napkins. Everything was torn apart and has been pieced back together. As recently as Wednesday morning, Davenport was still hoping the game against Duke was on for Friday, with a second game in Cameron Sunday against Howard.

To Bellarmine’s elation, the schedule held.

As the sun crept into the morning sky Thursday, Davenport went out for his daily run. The 62-year-old logged four miles around the Crescent Hill reservoir, puffing clouds of breath into the 27-degree air, as his mind raced. When he got to the office, Davenport wrote a thank you note to Mike Krzyzewski for scheduling the game, hoping to hand-deliver it Friday.

Then the Knights practiced Thursday morning in their own gym before embarking on the eight-hour bus ride to Durham. (They opted not to fly to minimize contact with the outside world and keep their team healthy.) After practice, Davenport read his team a text he received from a retired Louisville Metro Police officer, George Rodman, whose son and fellow officer, Nick, was killed in the line of duty in 2017:

“Coach D, in this crazy world, life experiences are invaluable. When you experience a tragic loss you’re always searching for a ‘ray of sunshine’ in life. Please tell the team they’re more than basketball players, they are the ‘ray of sunshine’ that helps us put one foot in front of the other. They give us something to be excited about! We will be watching and cheering. Have a great year!”

Scotty Davenport couldn’t get through reading it to his team without tears.

If the baptism is Friday, conception came in June 2019. That’s when the small Catholic college in the Highlands neighborhood of Louisville was announced as a member of the Atlantic Sun Conference. (Davenport received a congratulatory call then from Pitino, who touted him for the Bellarmine job.) Official delivery date was July 1, 2020, when school president Susan Donovan hit “send” on the paperwork to NCAA offices.

On that day, the Birth of a Program, Davenport walked into a darkened Knights Hall, sat down in Section 208 and cried.

The winningest coach in Bellarmine history took over a program coming off five straight losing seasons and by year four had the Knights in the Division II tournament sweet sixteen. In 2011, Bellarmine won the D-II national championship, then made three subsequent Final Fours. Davenport built the thing, and July 1 was the emotional payoff.

The coach doesn’t just wear his emotions on his sleeve; he wears them on his trousers, his collar, his forehead … everywhere. North Carolina coach Roy Williams has declared himself the corniest man in college basketball, but he better make room for the new guy. The guy whose ring tone on his phone is “One Shining Moment.” The Louisville lifer who will tell stories for hours about growing up here and wanting to make his hometown proud.

“If a guy like me can get right here, right now,” he says, “anyone can.”

Davenport lived at 1508 Central Avenue, just a few blocks from Churchill Downs, in Louisville’s gritty South End. (There are few things he loves more than holding court in the mornings of Kentucky Derby week in the Churchill barn area.) His father, Lawrence, died of a heart attack on Halloween when Scotty was 9 years old. Raised by his mom, Evelyn, who had a sixth-grade education and worked for 43 years as a hair stylist, he rode the city bus to junior high. He was not blessed with abundant athletic talent, but had an unquenchable love of basketball and played at Iroquois High School.

That quickly channeled him into coaching after college. The first job was as a graduate assistant to Crum, then as an assistant coach for one season at Virginia Commonwealth, then back home as the head coach at Ballard High School.

In his first two seasons, Ballard was part of two epic state championship games. The Bruins, led by sophomore and future NBA star Allan Houston, lost the 1987 title in overtime to Clay County, a rural school from deep in Appalachia led by future Kentucky guard Richie Farmer. In the 1988 rematch, Ballard withstood a 51-point barrage from Farmer to gain revenge.

The second game garnered national attention and brought ESPN’s “Scholastic Sports America” show to town to cover it. The fresh-faced reporter on the story for ESPN: Chris Fowler, the current face of college football for the network. After Ballard won, Davenport cajoled Fowler into joining the victory party at Gerstle’s Tavern, and convinced the owner to keep the place open all night.

Crum brought Davenport back to his staff in the mid-1990s, and Pitino wisely chose to keep him on staff for institutional memory when he took over in 2001. But that job came with one condition: Davenport had to lose weight. Pitino’s famous preoccupation with his players’ conditioning didn’t stop when it came to his staff.

“Think of all the things your dad never got to see you do,” Pitino said to Davenport before putting him on a workout regimen.

At the time, Davenport weighed 249 pounds. Within a year, he’d lost 78. He’s kept the weight off ever since.

As with most Pitino staffers, there was always a chance for upward mobility. When Bellarmine opened, Davenport jumped at the chance to be a college head coach in his hometown. He set the same hard-work expectation for his players that had guided his life, and told them that meeting expectations might require some extra hours.

“The back door [to the gym],” Davenport says, “if you yank it hard enough, sometimes it opens. And the ball rack, I set it right by the office door for a reason. I can tell if they’ve been used.”

The wins piled up, and Bellarmine found its niche in a basketball-mad city preoccupied by rival powers Kentucky and Louisville. The Knights were Switzerland. And a fun Switzerland at that.

“Everyone in this town can argue every day about red and blue, and one side hating the other,” Davenport says. “But they can all like us. Two guys sitting in an office arguing all day can say, ‘Let’s go watch Bellarmine,’ and eat popcorn together and cheer for the same team.”

What few people ever saw coming—including Davenport—was Division I status. Lacrosse actually paved the way, moving to D-I in 2005. Given the basketball program’s prowess, the school gradually started envisioning the entire athletic program joining the big-time.

Sitting in Section 208 on July 1, Davenport had one more reason to be emotional. A few feet away was a plaque honoring his late mother, who sat there in her wheelchair in later years for home games. If Lawrence and Evelyn could have seen him then …

On July 5, Bellarmine welcomed its first Division I basketball team back to campus. They had physicals, checked players into dorms, and had a meeting on COVID-19 protocols. Then Davenport herded all the players into Section 208 for a quick talk.

The theme: privilege and opportunity.

“What about those Cincinnati soccer players?” he asks, referencing a program that had just been eliminated. “You think they’d like to be you? What about all the players that came before you here? You get a chance to win the first Division I game in school history, and when that happens I’m going to shake the other coach’s hand and then sprint to watch you.

“You feel lucky now? Nobody in the history of this place is going to do what you get to do.”

Davenport asks the veteran players who their opening opponent was in 2019.

“Northwoods,” comes the response.

“Oh!” He shoots back. “This year it’s UCLA.”

(Or was.)

Then he asks who the second opponent was in 2019.

“Saginaw Valley.”

“Oh! This year it’s Duke.”

The players dispersed to play pickup, while Davenport went into his office. He and his wife, Sharon, had spent the previous night at Costco buying snacks for the locker room, laying out practice gear, putting new name plates on the lockers. At a D-I startup, the head coach’s duty list is long.

“These guys left here last spring disappointed they didn’t get to play in the D-II tournament,” Davenport says. “They come back staring UCLA and Duke in the face. You think things changed in your life in the pandemic? I’ll see you and raise you one.”

That was in the swelter of a Louisville July. By early December, when it was time to get on the bus and actually stare Duke in the face, everyone was wearing coats—everyone but Davenport, bustling around the parking lot in a T-shirt that said, “RISE.”

A son of Louisville’s gritty South End has risen, and brought a basketball program with him. Next stop is the first stop in a newborn Division I basketball program’s slightly miraculous journey: Cameron Indoor Stadium.