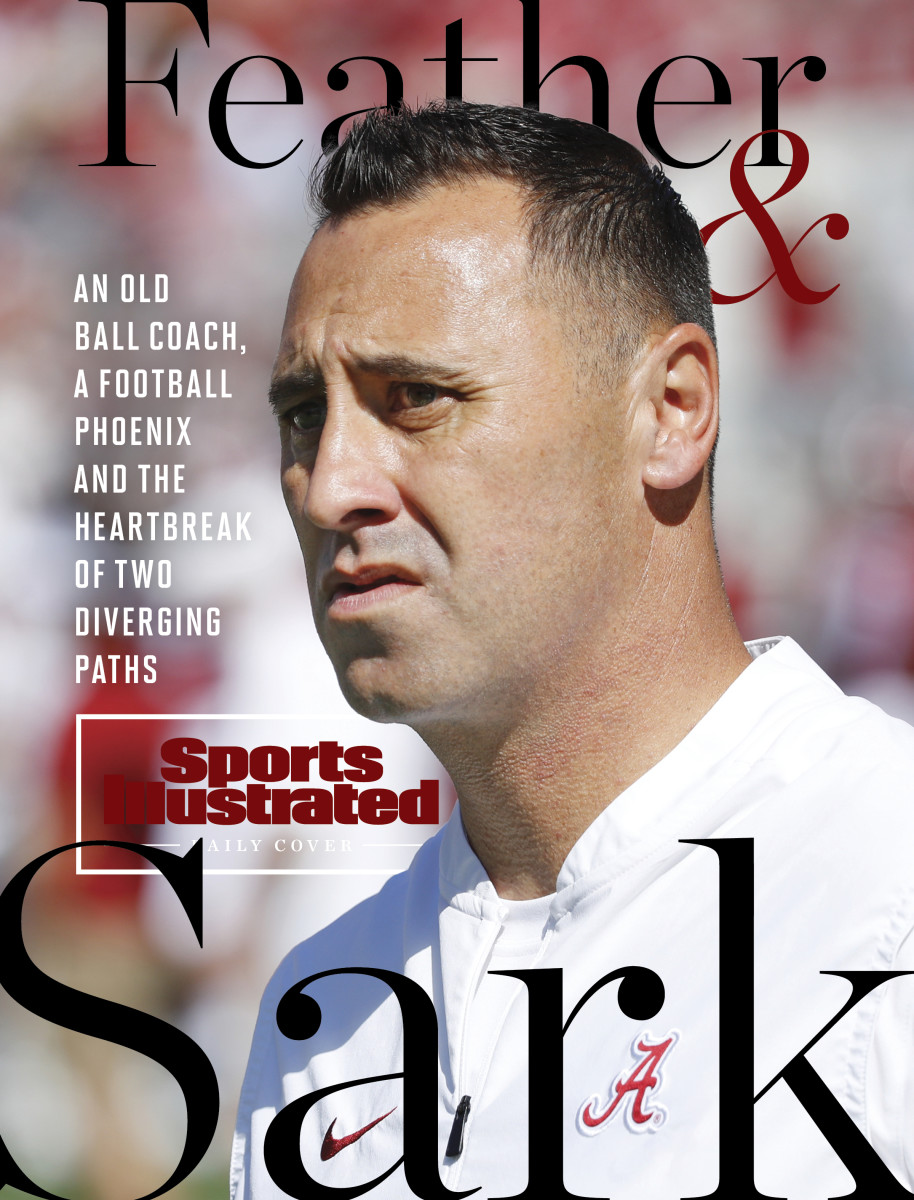

The Rise of Steve Sarkisian ... And the Decline of the Man Who Got Him Here

Memories come to him like flashes of light. The old football coach reaches back in his mind, grips what he can and hurls it into the air.

One word here. Another there.

Football.

Volleyball.

Catalina.

John Featherstone—better known simply as Feather, the fiery, passionate and championship-winning coach who for three decades ruled California junior college football ranks—is in a memory care facility near his home in Redondo Beach.

The 71-year-old last coached football in 2015, last played volleyball last year and last visited Catalina Island on Aug. 5, two weeks before a seizure left him listless and hospitalized. Seven years into dealing with Alzheimer’s, the latest medical event further hampered a once mighty man.

Physically, he is mostly fine, having now recovered from the seizure. He laughs, smiles and even dances to old hits like “Sweet Caroline.” He can and has thrown and caught a football. He hugs, he kisses and he still flirts with the ladies.

Mentally, he is not fine. He has been unable to use a phone for three years. Well before that, he stopped driving altogether. The most simple tasks, such as removing a shirt from his dresser and slipping it onto his torso, are impossible. Months ago, he stopped riding his bike to the beach because he would lose it so often.

His speech is now slipping, and communicating with him through FaceTime has grown difficult. Because of the pandemic and an outbreak at the facility this fall, no one from his family has seen him since November. The family’s financial resources are dwindling, putting his stay at the care home at risk.

Featherstone’s situation got tougher on Saturday. He tested positive for COVID-19. He’s now further isolated from the world, quarantined in a separate wing of the facility in which he’s spent the last several months, his family hoping he does not develop symptoms.

They FaceTime with him quite often. He says a word here or there.

Football.

Volleyball.

Catalina.

But there is another word he utters. The old football coach reaches back into his memory bank, recalling the young baseball player who he persuaded to play football and the software salesman he first hired as a coach.

Sark.

***

He used to call him Stevie, not Sark.

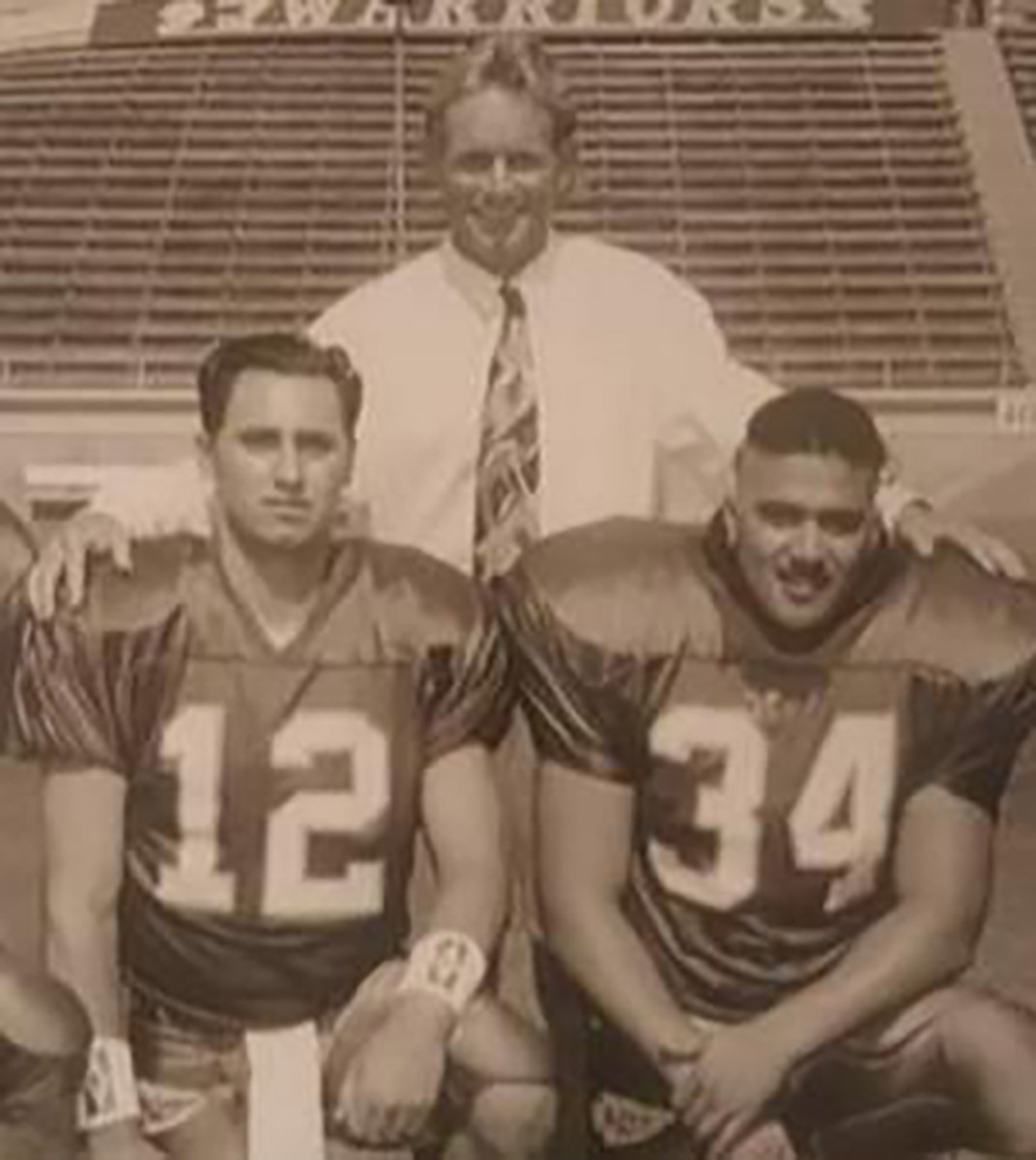

In 1993, when Steve Sarkisian arrived at El Camino College, a junior college football powerhouse on the outskirts of Los Angeles, he was a failed college baseball player who’d transferred from USC before completing his freshman year.

He was done with football, or so he thought.

Then John Featherstone entered his life as his new P.E. professor. Having watched Sarkisian play high school ball at nearby West Torrance, the coach badgered Stevie to give football another crack.

So during the final week of spring practice that year, Sarkisian relented. He agreed to throw passes at practice. Two years later, he left El Camino as its most decorated passer, then signed a scholarship with BYU, starred as a record-breaking QB for LaVell Edwards and then found himself back in the South Bay area selling software.

He casually dropped by an El Camino practice one day and there was his old P.E. teacher, relentlessly pursuing him again. “Come coach!” Featherstone told him, recalls Gene Engle, a longtime assistant at El Camino.

Sarkisian began coaching quarterbacks, eventually called plays from the booth and, after that season, was hired at USC as a graduate assistant.

“The rest,” Engle quips, “is history.”

Sarkisian is the most accomplished branch on Featherstone’s coaching tree, made more certain with his hire over the weekend as the new head coach at Texas. It is truly a second-chance story, the details of which have been exhaustively reported. Fired at USC for substance use. Checked into a rehab clinic. Cleaned up his act. And then joined forces with Nick Saban at Alabama to assemble one of the country’s most explosive offenses.

Before beginning full-time duties with the Longhorns, he’ll lead the No. 1 Crimson Tide (12–0) into the national championship game next Monday against Ohio State (7–0) in Miami. Across the country, some 2,700 miles away, his old coach, the man who sparked his career in the sport, cannot comprehend what his ex-pupil has accomplished.

“I don’t think he knows what’s happening,” says Diane Featherstone, the coach’s wife of seven years.

The two married just before John Featherstone was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s. This is a late-life love story that began with a courtship in 2009 and still hums along today. Diane, 77, cared for John until she couldn’t. She and John’s four daughters agreed to send him to a home earlier this fall after he recovered from the seizure.

Diane hasn’t seen her husband since Nov. 21.

“I used to go to see him and he’d cry in my arms, he was so happy to see me,” she says. “Now I can’t do that and it’s killing me. I see him on FaceTime and that’s it. Sometimes he knows me and can focus. But if the nurse leaves the room, he doesn’t know where to look. I tell him I love him all the time. One time he told me, ‘I love you, too.’ ”

Signs of the disease were obvious in John’s final two seasons as coach at El Camino in 2014 and ’15. Assistants noticed him repeating himself. He’d forget a player’s jersey number or name. Engle, his right-hand man for 31 seasons at El Camino, assumed many of his friend’s duties late in his tenure.

When healthy, Featherstone reminded Engle most of Lou Holtz, a small figure in stature who inspired such stirring passion among his players and exuded so much intensity.

But that man, the one who won 214 games, 11 conference championships, two state titles and the 1987 national championship, was fading. The guy who inspired thousands of players—including ones who went on to the NFL like Marcel Reece, Matt Simms and Antonio Chatman—delivered the most fiery pregame speeches and called nearly every offensive play, was deteriorating in front of everyone’s eyes.

“That was a tough part to watch,” says Ryan Winkler, an assistant at El Camino who played for Featherstone and was on staff for his final years. “He was still swimming in the ocean each morning, playing volleyball and coming to practice. He was healthier physically than anybody out there including players. Mentally, he wasn’t there.”

Alzheimer’s is a brutal disease. Brain cells themselves degenerate and die, eventually destroying memory and other mental functions. Medications and management strategies may temporarily improve symptoms, but no cure exists. The end result is almost always the same. Life expectancy after diagnosis is about three to 11 years, according to the Mayo Clinic.

“I’ll be honest,” Winkler acknowledges, “a part of me wants to remember him for how he was.”

For years, family and friends kept his diagnosis a secret. He was in denial about the illness for a while, says Diane, carrying on with life and coaching as if nothing were wrong. The two didn’t discuss the topic. Alzheimer’s wasn’t mentioned.

When doctors found traces of trauma in Featherstone’s brain which they say likely stem from injuries sustained in childhood and while playing football, they didn’t talk much about that either. “Concussions,” says Diane, who holds no resentment toward a game that her husband built his career and life around (every Saturday, you can still find her watching college football from her couch).

But inaction was not an option. Last fall, they publicly revealed their secret.

“We have no choice,” Diane says.

Engle and Diane recently began a GoFundMe page to keep John at Belmont Village Senior Living. While that effort has generated nearly $80,000—much of it from former players—it’s only enough to keep him at Belmont for seven more months, give or take.

The memory care facility provides John more amenities than a normal senior home. He takes medication and participates in memory exercises to slow the deterioration. It’s a more comfortable community setting versus “just sitting at a senior home and staring at a TV,” Engle says.

When the GoFundMe first went live, the outpouring was jaw-dropping. Some gave $10, others $500 and several donated four figures. The donations often came with a phone call, email or face-to-face interaction.

“As hard as this disease is, it has brought a lot of people out sharing so many stories about him that we may have not heard,” says Keegan Felix, one of Featherstone’s daughters. “We have had players come up to us and say, ‘Your dad saved my life. I would have been dead or in jail.’ ”

Some donations came from players who never even lasted at El Camino.

“You start going down the GoFundMe list and there are guys on there that you’d never think would be on there,” says Derrick Deese, a former NFL offensive lineman who played for Featherstone at El Camino. “They now get it—they learned a lot from him. It wasn’t just about football. It was bigger than football.”

Through Deese, the family got a message to Sarkisian about his former coach’s condition and the fundraising campaign. A day afterward, an anonymous four-figure donation appeared on the GoFundMe page, says Deese.

***

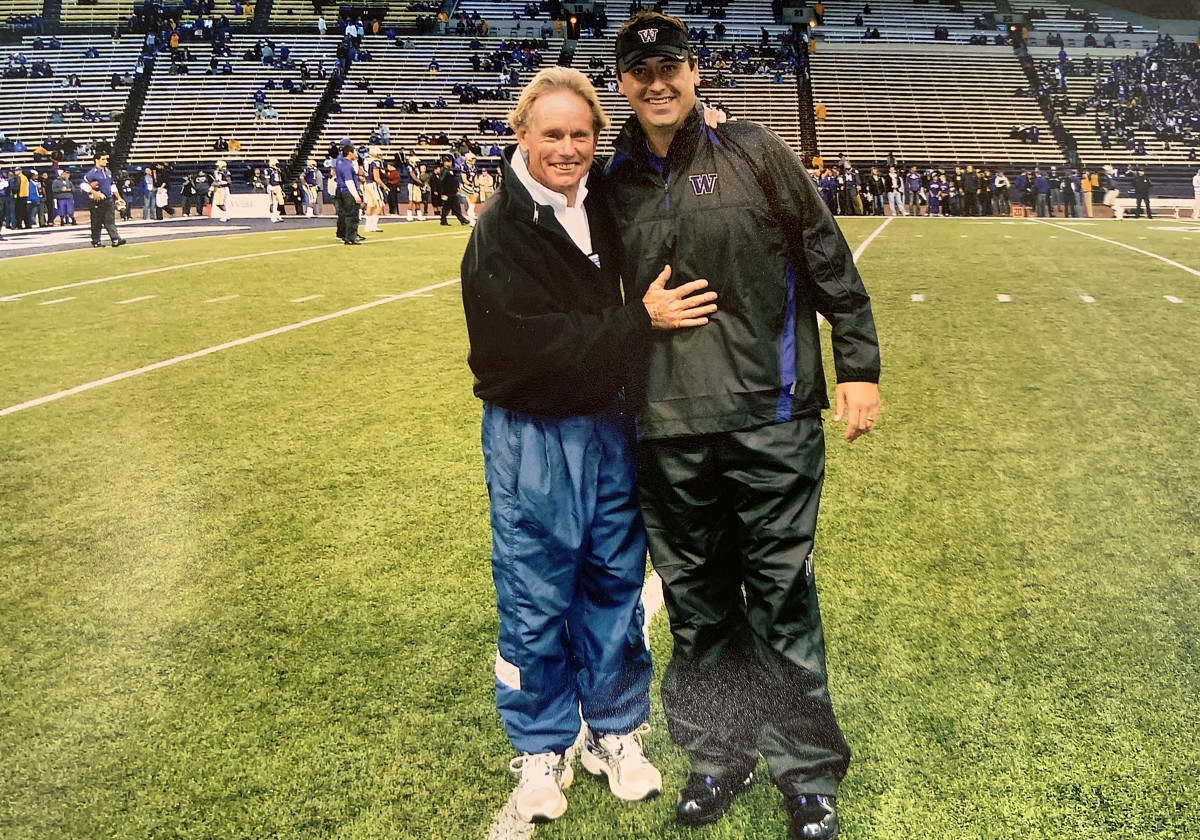

Feather and Sark were close for years. But after Sarkisian’s firing at USC, communication between him and other members of the El Camino staff stopped, Engle says. The last time the two saw each other was at a spring practice on USC’s campus in 2015, a few months before Sarkisian lost his job for alcohol-related issues. A couple of years before that, the Featherstones traveled to a Washington Huskies game in Seattle while Sarkisian was coach. Sarkisian even allowed his old coach to speak to the team. Diane was there as her husband, in the early stages of his secret disease, delivered an impassioned address.

Featherstone watched the game from the field, once again sharing a sideline with his former player and assistant. The trip was significant. It kicked off Diane and John’s retirement plan—to travel each weekend to a football game, exploring the city and campus. The retirement plan never really materialized. The disease took it from them.

And now, years later, a virus has taken away their ability to even see one another.

“It’s heartbreaking,” Diane says. “But what’s interesting is over the last year he’d only bring up certain names. He always said Sark. ‘Wonder where Sark is.’ ‘What’s Sark doing?’ As we were watching football, I’d tell him that Sark is coaching that game.”

As his condition has deteriorated, he could only recently utter his name.

Sark.

Diane believes that the simplicity of the word—four letters and a single syllable—makes it conducive for her husband to pronounce.“

Anytime he’d see him on TV, he’d say ‘Gosh, look at him!’ ” Felix recalls. “He was so proud of him.”

In the most recent FaceTime with Featherstone, Diane asked her husband how he was feeling. He mumbled something, and according to the nurse, he said, "Happy."

She's attempted to explain to him the details of Sark landing his big new job, but whether he understood or not remains a mystery. In the past, when he was more coherent, he'd watch football, see Sarkisian on screen and immediately sit up. He'd get anxious and believed that he should be there with his pupil. "We've gotta go now!" he'd tell Diane.

In many ways, Featherstone saw himself in Sarkisian. They're not the most physically gifted men, but natural-born leaders who could captain a huddle, deconstruct a defense and scheme offensively.

“It was so fun to get on the board with Stevie. He was like a mad scientist,” Featherstone said in an interview in 2017 with 247Sports. “I could tell he was a leader. He didn’t want to be in the back of the room—he wanted to be in the front. I was that guy, too.”

That was one of the last public recorded interviews in which Featherstone participated. In the video, he is seated on a bench near the Redondo Beach Pier. He’s smiling incessantly while speaking about his former quarterback, the Pacific Coast breeze blowing through his slicked-back hair. It’s a lasting image. At the time, few knew about the disease slowly encroaching on his life.

In November 2019, in a ceremony that he attended, El Camino named its football field after Featherstone. He came bursting out of the tunnel with the 2019 Warriors and their new coach, racing onto Featherstone Field as if he were still leading the squad.

A bronze plaque now hangs at the stadium detailing Featherstone’s on-field, numerical accomplishments. But it is the plaque’s six other words that reverberate.

“Mentor, teacher, coach and loyal friend,” it says.

Even without his presence in public life, John Featherstone’s legacy lives on through those he inspired. At the top of the list is one of college football’s most brilliant and innovative minds: the new head coach at the University of Texas.

Sark.