The Old-School Coach and the New-School QB: How Mac Jones Was Built

JACKSONVILLE, Fla. — Have you ever read to a man on his deathbed?

Physically sat next to him, looked him in the eye, gripped his hand, and read to him? He knows he’s dying. You know he’s dying.

Death is not an appealing presence, not at all. But no one should die alone. And no coach, especially one of the greatest high school coaches in American history, should pass without knowing the full extent of his labor.

That is why, during February of last year, in a hospice facility here in northeast Florida, Clint Drawdy read aloud dozens of letters to his father-in-law, who lay before him, in and out of consciousness.

“Dear Coach,” they’d begin, “thank you.”

“Coach,” one started, “I love you.”

Corky Rogers mustered what he could—a head nod, a slight smile, a low grumble.

In the final 10 days of Rogers’s life, as cancer consumed his body, his family received more than 100 emailed letters from former players. Some even sent video clips.

It was a massive wave of heartfelt goodbyes in which stories, then unknown to the coach’s family, emerged. One ex-player, for instance, named his son after Rogers’s real name, Charles. Another said the coach once bought him shoes when his family couldn’t afford them. The stories went on and on.

But one former player was different from the rest. The player, a quarterback, finished his high school career in the same season as Rogers retired, 2016. They went out together—coach and quarterback.

Before Rogers entered hospice, the player called the coach and they talked. Anyone who knows Corky Rogers knows he doesn’t show emotion. He especially does not cry.

But toward the end of the conversation, after the goodbyes and the thank-yous, after the reminiscing and remembering, his former quarterback made him a promise.

Mac Jones told his coach that he was dedicating the 2020 football season at Alabama—every pass, every touchdown, every win—to him.

On that day, Corky Rogers cried.

***

The bond between a football coach and his football player can be complicated.

That went double for Corky Rogers. His draconian coaching style, while producing a state-record 465 wins and 10 state championships, often resulted in a love-hate relationship with his current players. Only years later would they realize their appreciation for the man.

“Everything about him was old school, but it was with a purpose,” says Jake Lundgren, who played for Rogers at the Bolles School, a private, affluent institution on the banks of the St. Johns River. “People would benefit from his style today. It was a teaching moment for kids raised privileged.”

At his practices, there was never music, and barking at players was quite common—especially quarterbacks. He demanded perfection. Rogers, in fact, was known for making his quarterbacks run sprints for mistakes. Touchdown passes thrown to the wrong receiver were considered mistakes (In fact, wildly enough, that’s how Jones got his first playing time; he replaced the starting quarterback who had completed a touchdown to the wrong guy.)

If you think that’s an antiquated approach, you should hear about his offense. Rogers began his career running the triple option before evolving to the Wing-T, a 70-year-old scheme that has, in large part, been abandoned by the sport.

If you were late for one of his practices, you ought not bother showing at all. And if you didn’t wear white cleats and white socks, you’d be asked to leave. The Oklahoma Drill, when two players collide in front of a circle of teammates, was a mainstay, and, at times, even quarterbacks and kickers weren’t excused from it.

Rogers never coached while using headsets, and he never signaled in playcalls. His quarterback, after each play, got the next call from Rogers by physically running to the sideline.

And good luck trying to get ole Cork, as friends called him, to operate the internet or use his flip phone, which he kept in his vehicle’s glove compartment, the battery often dead. He did not believe in seven-on-seven football, dismissed online recruiting reporters and wholeheartedly hated social media. He believed the latter would be the downfall of society.

If anyone was old school, it was Corky Rogers. And if anyone was new school, it was Mac Jones.

Even at a young age, Mac embraced social media, especially Twitter. He was individualistic, wanting to wear different color shoes or socks. Mac wanted to celebrate touchdowns, thrusting his arms into the air and rubbing the feat in the faces of his competitors. A class clown whose charm made the school girls cackle, Mac brought the same playful and silly manner to the football field.

Mac and Corky were opposites.

“Corky and him kind of battled it out,” says Holly Jones, Mac’s mother.

Rogers rode Mac so hard, in fact, that he nearly quit. Gordon Jones, never involved with his son’s coaches, broke protocol this time. He met with Rogers to politely relay a message: Mac is his own worst critic, so go a little easier on him.

Recruiting caused the most problems. When Mac marketed himself to coaches on social media, Rogers snapped at him. When Mac traveled to college camps, Rogers scoffed. The team had no social media presence, then an emerging avenue for college recruiters, so Gordon set up and ran an unofficial Twitter account for the Bolles football program. College coaches looking to speak with Rogers were often sent a number to a phone that hung on the weight room wall.

“Weight room!” kids would answer. “Oh, he’s not here. Call back later.”

To compound the issues, Mac was operating an offense from 1958. And while the Bolles Bulldogs passed more than usual out of the Wing-T, Mac took almost every snap under center while other high-profile high school quarterbacks captained shotgun-based, five-wide schemes.

At high school and college camps, coaches would watch Mac throw and then turn to his parents confused.

This kid is playing in a Wing-T? Why?

***

The miniature white rubber footballs came whistling through the air toward Mac Jones.

This was an annual tradition. The children at the Bolles (Fla.) School—kindergarten through 12th grade—lined a roadway on campus for the homecoming parade. Varsity football players slowly moved by in jeeps, convertibles and pickup trucks while tossing throws to the sea of kids.

Little Mac wasn’t as excited about the throws or the players as he was the coach. Corky Rogers was a legend at Bolles, in Jacksonville and in the state of Florida. To eight-year-old Mac, he was God.

“That’s all he wanted to ever do was play for Corky,” Holly says. “That was his dream, his first dream.”

As a young kid, Michael McCorkle Jones saw Corky in his own name, quite literally. McCorkle was Holly’s maiden name. McCorkle. McCork. Cork. Corky. You get the point.

Mac’s classmates often referred to him as Little Corky, Holly says. When he turned seven, Mac’s birthday party’s main event was attending a Bolles football game. His mother still has the photo of him and his friends sitting in the stadium bleachers.

It was around this time that the Joneses realized their son’s athletic talent wasn’t the same as their own. Holly and Gordon played college tennis. Mac’s dabble in football became serious when they picked him up from a youth football camp one day and Mac hopped in the car wearing a golden shirt.

“What is that?” Holly asked.

“It’s the Golden Arm Shirt,” little Mac blurted excitedly. “They say I have a bright future.”

Holly turned to her husband and winced. What had they told her little boy? She feared he’d eventually be disappointed.

But Mac kept throwing and throwing. He entered into two youth football leagues, quarterbacking one team on one night and another on the next. He began attending more youth camps. For someone so scrawny and young, Mac’s passing ability confounded anyone who witnessed it, including Joe Dickinson, a renowned quarterback guru who eventually tutored Mac for years.

“He was natural at spinning the ball,” says Eric Yost, Mac’s Pop Warner coach and the then son-in-law, coincidently, of Corky Rogers.

When Mac joined Bolles’s varsity team as an eighth-grader, one thing was clear: There was no way they could put him in a game. He was 5' 5" and weighed about 80 pounds, says Kevin Fagan, his quarterbacks coach with the Bulldogs. “But I said to people,” Fagan says, “if he ever grows, look out.”

Mac did eventually grow, at least enough to star at Bolles. He grew wise beyond his years, too. He could read defenses, see the entire field and make the grades in the classroom (after all, he graduated with both a bachelor’s degree and a master’s from Alabama in fewer than four years, completing each with a 4.0 GPA.

It was his physical size that held him back for so long.

“Mac always threw better than any quarterback at any camp, but if you’re 5' 10", 165 pounds, you get the ‘Is this guy going to be able to survive the pounding?’ ” says Mac’s dad, Gordon.

Mac’s size didn’t matter to his coach. His toughness did, and Mac displayed his fortitude in his first real game during his sophomore season. He took hit after hit, leaped off the turf, ran to the sideline for the play call from Rogers and then took more hits.

Rogers was hard on Mac in the early years, but it was with good reason, says Linda Rogers, Corky’s wife. Corky would return home from practice and rarely ever speak about football. Home was his escape. But he’d talk, sometimes, about Mac.

“He felt Mac could take it,” Linda says. “He’d always say that.”

Mac evolved into one of the area’s hottest recruits, but he never really landed the big offer. For a while, his best opportunity was Kentucky. With Alabama, he was somewhat of an afterthought. It took Jake Fromm’s decommitting from the Tide and following Kirby Smart to Georgia to open a spot for Mac, says Gordon.

Neither Florida nor Florida State wanted Mac even if he wanted them (especially the Gators).

Late in the recruiting process, he showed up in Gainesville for a camp and wowed everyone with his arm. The Florida coaches pulled aside Gordon and Holly. They were befuddled.

Who are you and where have you been?!

The skinny kid from the private school that ran the Wing-T was raised just 90 minutes away from UF’s campus. Florida coaches took the Joneses up to their football offices to check out their recruiting whiteboard. Mac’s name was nowhere on it. And it was too late for an offer. Their class was full.

Mac visited an FSU camp only because Bolles teammate Ahman Ross had an invitation, so he tagged along. Mac threw next to the colossal Joey Gatewood, one of the class’s prized quarterbacks, standing 6' 4" and weighing 230 pounds. No one paid attention to the scrawny kid next to him rifling passes across the field.

“Mac was dog poop to them,” Holly says.

Even Wake Forest didn’t pull the trigger on Mac. He attended three camps there. At the last one, a Wake assistant coach walked up to Gordon and told him that Mac had not missed one single throw in three trips there.

“So he has an offer?” Gordon asked.

“Well,” the assistant said, “we’re going to wait until the end of the year to make a decision.”

***

Corky Rogers once coached a spring game from the back of a pickup truck parked beyond the end zone, his left leg in a cast and his hand gripping a walkie-talkie (this was 1988). On the other end, Wayne Belger, the interim coach who was partial to passing, heard the familiar voice come crackling through while he paced the sideline.

Run the ball more!

“I’d say ‘Coach, this thing isn’t working. You’re breaking up,’ ” Belger laughs.

Two months before that, a drunk driver struck Rogers while the coach left his vehicle to survey damage of a minor car accident in which he was involved. It shattered his leg with such force that doctors wanted to remove the lower portion of the leg, then connected only by skin. He refused to let them.

He endured 18 surgeries, needed his calf rebuilt through skin grafts and forever had a dangling toe. During a year rehabilitation process, he coached, first from the back of that pickup truck, then in a wheelchair and finally on crutches.

Years later, when he entered the hospital for a routine shoulder surgery, doctors found seven artery blockages. He underwent a septuple bypass, and two months later, he returned to the field just in time for spring practice.

“When I tell my players to never miss a practice and never miss a workout and to be totally devoted to the team, I better be doing it, too,” Rogers once quipped to explain his commitment.

This grit is part of the legacy of Corky Rogers, heralded as Florida’s best high school football coach. In 45 years as a head coach, he reached the state title game 16 times and never had a losing season.

He turned Jacksonville’s Lee High into a consistent winner and then transformed the Bolles School into a powerhouse. But Corky wasn’t all work. In fact, after every high school football game, he’d host a party at his home, and he spent most weekends watching his Jaguars play or golfing. He was competitive.

“He’d go out and shoot 79 and want to kill everybody around him,” says Fagan, the longtime assistant to Corky who was Mac’s quarterbacks coach at Bolles.

Out of himself, Corky demanded the world. Out of his players, he demanded even more. And that included his two daughters, Tracy and Jennifer. Early in his career, Corky doubled as the softball coach at Lee High, and Tracy played softball. He was so tough on her that she quit.

Later in life, Corky massaged the details of the story to use it as a scare tactic for his players.

“I cut her,” he told them proudly. “If I can cut my own daughter, I can certainly cut you.”

Corky was toughest on those he loved. Among those on the 2015–16 Bolles football teams, no player took the tongue lashing more than Mason Yost, Corky’s grandson who is now a sophomore tight end at Liberty.

“Mac was second but only to me,” Yost says.

Corky was hard enough on Yost that he’d often come home to Linda and express concern at the way he treated him.

“Well, call him!” Linda would snap.

No, Corky would say, I can’t do that.

Corky retired after Yost’s junior season.

“With me getting yelled at a lot,” Yost says, “when he retired, I was a little relieved."

After their coach-player relationship ended, granddad and grandson grew close. Yost last saw Corky last January, about a month before his condition deteriorated. The two spent time at one of Corky’s favorite retirement hangouts: the dog track.

When Corky’s condition worsened, Yost called his former teammates, including Mac. Let’s write letters, they agreed.

Yost knows Mac and Corky had grown close over the years. He has tangible evidence. Because Corky did not use a cellphone, he stored his contacts on a yellow notepad beside his home phone, all of them scribbled in ink. Only a few former recent players made it on this exclusive list.

Mac’s name and number were there.

Corky and Mac’s relationship evolved from the early years to his senior season. It’s hard to explain, says Mac. He coached him hard all four years, but there was something different during the last season in 2016. Corky treated him more like an adult, even if he did refer to him still by a nickname: Sunshine.

In that last year, Mac even made Corky laugh with his silly stunts. The two bonded over football. They’d escape in the corner of a halftime locker room, the coach’s arm wrapped around the shoulders of his quarterback.

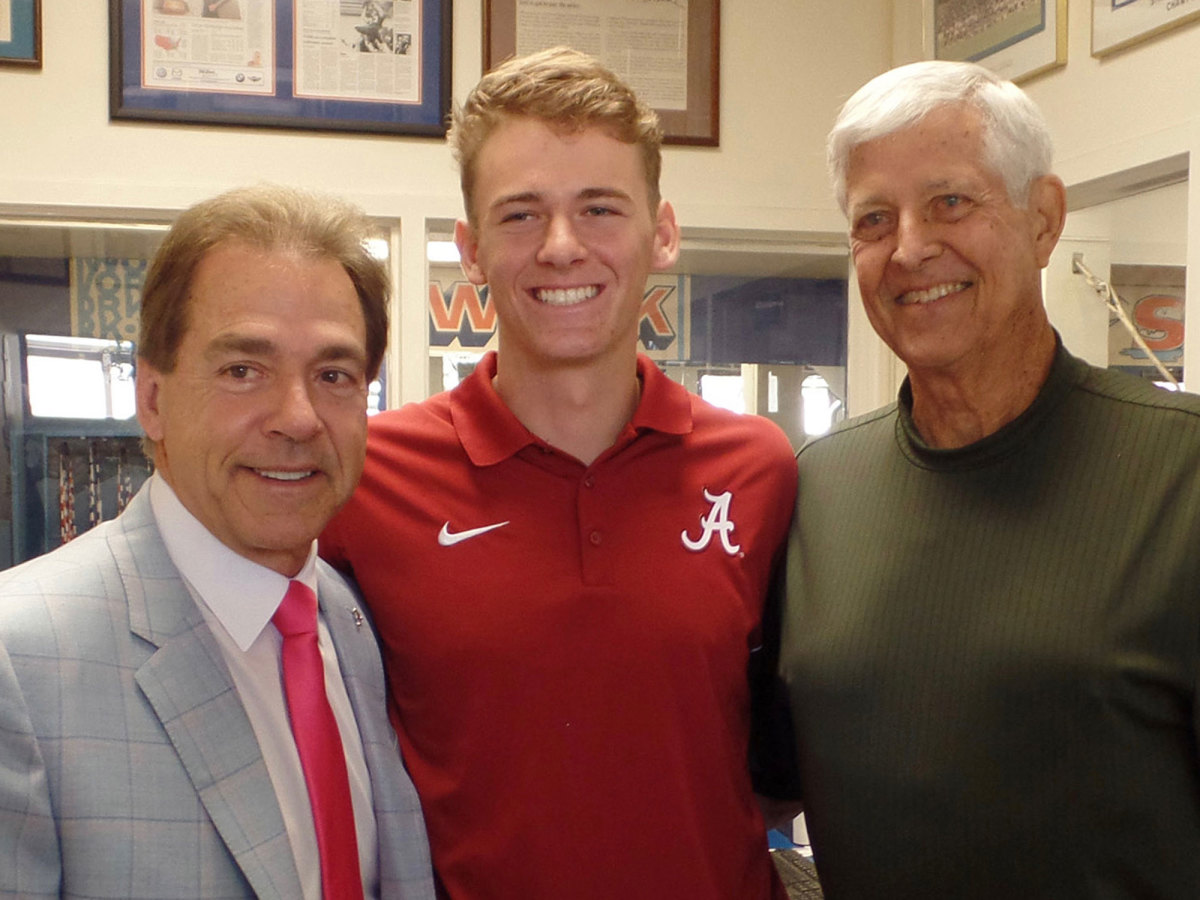

Today at Alabama, Mac keeps a photo of Corky and himself close by. He’s tough now because of Corky. He’s humble now because of Corky. And he gets rid of the ball so quickly because of Corky, too.

“He used to tell me that if I hold the ball any longer, it’ll hatch,” laughs Mac. “Like it’s an egg. I guess that’s where I get my quick decision-making from.”

That last year, Corky’s guard dropped and a small crack opened in his hard exterior. Still, he was never one to show too much affection. This is football, for crying out loud. It's smash mouth. It’s sweat and blood. There was no time for affection.

That is, until the end, during that final phone call, when player and coach finally told one another how they really felt about the other.

“I wanted to let him know he was one of the biggest reasons why I am who I am today, and I don’t know if I ever truly told him that,” Mac says. “He told me how proud he was of me and that I was his favorite quarterback. That conversation … I’ll never forget that conversation. I wish I could have recorded it.

“I remember him saying he loved me and me telling him I loved him back. We hung up and that was that.”

***

Linda Rogers says her husband’s final two weeks were the hardest of her life.

Corky was too prideful to be put in a home or have a live-in nurse. Linda became his caretaker. She slept about one hour a day those final couple weeks. Corky was back and forth from hospitals. The rescue team and paramedics were at their home far too often.

By then, Corky was frail and had trouble walking. One night, he fell and Linda couldn’t hoist him up. He lay on the floor looking up at her as she grabbed the phone to call for help.

No, Corky told her, I’ll sleep here on the floor. Linda pushed back, but it was a losing battle. So, she threw him down a pillow and blanket.

He spent the night on the floor.

“Corky was not one to ever give up,” Linda says. “He would say to me sometimes, ‘Linda, I don’t think I can take it anymore. Every part of me hurts.’ ”

Remember Corky’s leg injury in 1988? Ultimately, that was behind his decline late in life. Years later, while hospitalized for that heart surgery, doctors discovered Hepatitis C within Corky. He had picked up the viral infection during a blood transfusion for his leg.

This man had gone through a lot in life. Run over by a drunk driver, seven bypasses and now, 25 years later, learning he’d been injected with infected blood.

“I jokingly say he’s the biggest cat of them all,” says Tom Collins, the longtime middle school coach at Bolles. “He didn’t have nine lives. I think he had 10.”

Just weeks before the start of what would be his final season as coach, Corky spat up blood while on a golf outing and was rushed to a hospital. Hepatitis C had damaged his liver. It was shot.

Instead of retiring, he pushed through that 2016 season. Even if it meant having his stomach drained each Monday. Even if it meant his skin turning a yellowish color. Even if it meant being restricted to a golf cart during practice.

One day, he climbed out of his cart to bark at players and nearly collapsed on the field. Drawdy, his son-in-law watching nearby, rushed onto the field to beg him to stop.

“I’ll stop when I can’t go any longer,” Corky said.

“It was tough to watch but inspiring at the same time,” says Lundgren, Mac’s former teammate at Bolles. “He showed up and gave us everything he had. That’s what heroes look like.”

Most players on the team didn’t think their coach would survive the season. Instead he lived more than three years longer until, in February 2020, just before the pandemic arrived in the U.S., cancer was discovered on his kidneys. It quickly spread. His liver. His lungs. His brain.

Mike Barrett, another longtime Corky assistant at Bolles, believes his former boss never would make it in coaching today. His old-school approach is no longer popular, his rules too strict. And social media? No way.

“It worked out the way it should have in the big picture,” he says sadly.

Toward the very end of his life, dozens of players wanted to return to visit their old coach. Corky declined. He wanted no one, not even some family members, to see him in this state. He was a football coach and that’s how football coaches are. He wanted them to remember him as that tough, healthy leader pacing the sidelines and calling plays.

He even told his own grandson not to return home. Instead, Mason Yost wrote a letter to his grandpa. They all did. Mac, too.

So there, by his father-in-law’s bedside with tears in his eyes, Drawdy read aloud the letters. There were so many of them that he split them up, reading them in 20-minute segments.

“I’d read a few and then we’d pause and the doctors would come in,” Drawdy says. “It was like a movie, how it all went down. It was one of the coolest things I’ve ever witnessed.”

Before his death, the final words Corky Rogers heard were from his players.

One of them promised him a season.

“I do think about him a lot, on a daily basis,” Mac says. “Whenever someone asks, ‘Who helped you get here?’ He’s one of the first people to pop into my mind. I do love that man.”