With Recruiting in Mind, States Jockey to One-Up Each Other in Chaotic Race for NIL Laws

JACKSON, Miss. — Within the marble halls of the Mississippi State Capitol, the topic of college football is never far away.

Home to two of the SEC’s plucky underdogs, Ole Miss and Mississippi State, legislators here are always striving to make up ground on neighboring states that have more historic football powerhouses. In fact, last summer, lawmakers replaced their state flag after the NCAA and SEC banned the Rebels and Bulldogs from hosting athletic championship events in a state whose flag brandished the Confederate battle symbol.

Nine months later, another piece of college sports-themed legislation is working its way through this building. This time, a bill that would grant Mississippi college athletes rights to earn income from their name, image and likeness (NIL).

Some legislators here are even pushing through the bill despite their own opposition to it.

Why?

Crootin’.

“I don’t think any state is happy about this legislation, but we’re seeing this as a necessity,” says C. Scott Bounds, a Republican member of the Mississippi House of Representatives who’s helping oversee the bill’s journey through the state’s legislative process. “We don’t want to lose a competitive edge in recruiting, both athletically and academically, especially against those in the Southeastern Conference.”

While a national NIL bill seems many months away and the NCAA’s own legislation is delayed, the states are taking matters into their own hands.

Dozens of state legislatures are close to adopting laws governing athlete compensation within their borders. Their work was paused last spring because of the pandemic, but state lawmakers are returning to their capital cities this spring with NIL on their minds.

The NIL blitzkrieg is thundering through the halls of state capitol buildings across the country. Bipartisan bills are swiftly marching toward the end of what is normally a slow-moving legislative journey, sometimes even passing with unanimous consent. States are jockeying to create more advantageous NIL laws than their rivals, one-upping each other in what’s turned into a bit of a chaotic race.

If this NIL jaunt were a derby, it has hit the final stretch, each state rushing legislation in time to catch the lead stallion, Florida, whose state NIL law goes into effect on July 1. At least a half-dozen states—Mississippi, Iowa, New York, Maryland, Alabama and New Mexico—are inching toward passing bills relatively soon. The Magnolia State, in fact, is on pace to adopt NIL legislation by the end of the month, poised to join six other states that have previously passed NIL laws: California, Florida, Colorado, Nebraska, New Jersey and Michigan.

“It’s like whack-a-mole keeping track of them all,” says Julie Sommer, a Seattle-based attorney and former college swimmer at Texas who’s now working for The Drake Group.

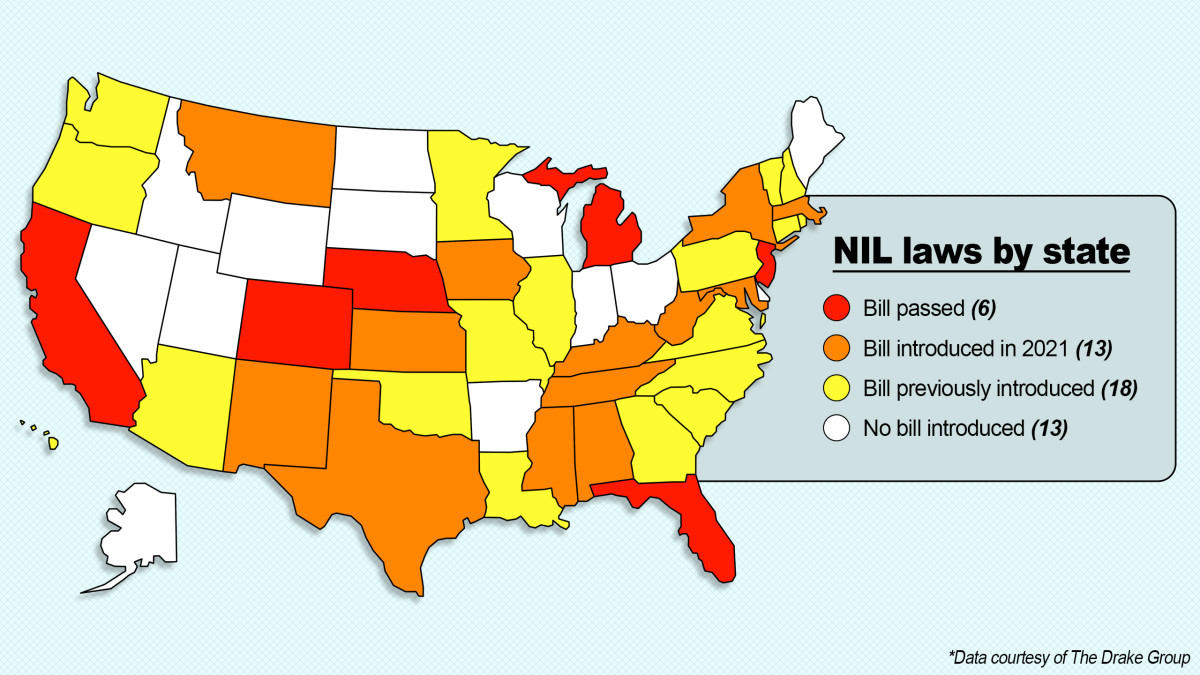

She has a computer full of spreadsheets and Word files dedicated to the monitoring of this sweeping trend of state NIL action. In all, 13 states have reintroduced NIL legislation this session and 18 more introduced bills last year. Six states that have reintroduced bills have an effective date of July 1 or even earlier.

“It’s the perfect storm brewing,” she says. “We’re seeing now that all these states are back in session and all these bills are popping up. We’re approaching the tipping point.”

These various state bills differ slightly in language, but their foundations are made up of the same basic provisions: (1) an athlete’s NIL rights cannot be restricted by schools and conferences; (2) athletes can hire an agent; (3) endorsement deals must be disclosed to the school; and (4) no prospective athlete can strike NIL deals as recruiting inducements.

But they are not all uniform. Some of the bills feature unique provisions and a wide range of effective dates. At least two states could see their laws take effect even before Florida’s. Alabama’s bill would kick in two months after the governor signs it, and New York’s bill would take effect immediately.

While most of these NIL proposals are exceedingly athlete-friendly, some are more restrictive than others. Mississippi’s bill, for example, allows a university to impose limitations on the date and time in which an athlete may participate in NIL events. Others are more permissive, with stringent regulations on schools. Iowa’s bill even places a cap on the number of hours per week a student can participate in athletic activity, and New Mexico’s bill prohibits schools from denying an athlete enrollment if they earned NIL compensation as a recruit.

At least a few bills blur the lines of pay-for-play. South Carolina’s bill, thought to be a longshot to pass, compels schools to set aside $5,000 per year in a trust for each football and basketball player and then to distribute the funds to them upon graduation. Alabama’s bill gives athletes the option to participate in NIL or receive $10,000 a year from the school.

New York’s bill requires schools to set aside 15% of their athletic department revenue for a wage fund to divide among athletes each year.

“This is a drumbeat you’re hearing from state capitals,” says Brooke Lierman, a Democrat and member of the Maryland House of Delegates, where she’s a co-sponsor of NIL legislation. “We are tangentially working with one another because we are fed up with the NCAA’s archaic and unjust rules. We’re going to act in the absence of federal leadership. If enough of us act, I think Congress will do something.”

In some respects, the states are passing legislation as a way to inflict pressure on federal lawmakers to adopt a universal policy to govern NIL. While there are six different NIL Congressional bills floating around Washington, the latest from Sen. Jerry Moran (R-Kan.), there are giant gaps, in both concept and scope, between Republican- and Democrat-backed legislation.

Meanwhile, the NCAA has delayed passing its own NIL legislation, likely until the Supreme Court rules on its case in Alston v. NCAA. The Court will review whether the NCAA’s eligibility rules regarding athlete compensation violate federal antitrust law, something that could dramatically shape the NCAA’s potential ability to stop state laws from taking effect this summer. The Supreme Court is expected to hear the Alston case on March 31 and deliver a ruling no later than the end of June.

In the meantime, states are in a race against one another, a concerning trend for many in college sports who believe chaos will reign come July. A handful of states will be operating under more lenient and athlete-friendly NIL laws while all others follow the NCAA’s more stringent NIL legislation, whenever it does pass.

“Some states will have an advantage early,” says Arizona State coach Herm Edwards. “It’s going to be a mess.”

It’s a “catch-22” for those schools in states that will have passed NIL laws, says Big 12 commissioner Bob Bowlsby.

“It puts the schools in their state in a very difficult situation,” he says. “They’ll find themselves violating NCAA rules at the same time complying with state laws. It might end up in court at the end of it.”

All of it sets up what could be a historic summertime court battle between the NCAA and the states. There are varying opinions on the issue, but many believe that by early June, the NCAA will file injunctive action to prevent the effective dates of state laws, arguing with the interstate commerce clause, which purports that a state cannot enact a law that prohibits other states to interact in interstate commerce.

Chip LaMarca, a Florida Republican lawmaker and the sponsor of that state’s groundbreaking NIL legislation, isn’t backing down. He believes that language in his legislation is lawsuit-proof and says that if the NCAA were to file suit, it would create a public affairs nightmare for an organization already struggling for public support. “They are on the losing side of history,” LaMarca says.

And what if a university in Florida were to follow the NCAA’s legislation instead of Florida’s own law? According to the legislation, that school would lose all financial support from the state.

“It’s difficult for a school to resist what’s going on among elected officials in their state,” says Bowlsby. “They are the very people who allocate annual budgetary allocations to the schools. It isn’t a good idea to be at odds with your elected officials.”

Others believe the NCAA may not file suit. Count in that group Tom McMillen, himself a former legislator who now runs Lead1, an organization made up of FBS athletic directors. It is not “feasible” for the NCAA to file suit against 20-plus states, he says. He expects the chaos of varying state NIL laws to trigger activity in Washington.

“If that patchwork comes out, Congress will have to do something,” he says. “They can’t let it get that chaotic.”

However, another option exists for a universal NIL law aside from a Congressional bill. It would come from the Uniform Law Commission, a nonprofit organization made up of more than 300 attorneys with a mission of providing states with drafted legislation on a number of fronts. The ULC is hoping to have NIL legislation ready for states to adopt by summer, says Gabe Feldman, a Tulane law professor who has been integral in crafting the proposal from the ULC. The idea is that states will replace their bill with the ULC’s own legislation, creating a universal bill across the nation.

Feldman has been following the NIL issue for years, watching a simmering cauldron bubble over and, finally, erupt in a chaotic mess.

“I think many had hoped we’d have more clarity by March 1, 2021,” he says, “but it’s gone the other way. Things are murkier than ever.”

In some respects, the chaos has already started. On a recent webinar with athletic directors, McMillen recalls a Florida administrator crowing about his state’s upcoming law. “States are bragging,” he says.

But on the recruiting trail, NIL isn’t a primary talking point, at least not yet, says a handful of coaches who spoke to Sports Illustrated under condition of anonymity. That said, they expect recruiting pitches to include NIL soon enough, pitting schools with more open NIL laws against those that must follow NCAA code.

What if a five-star football player, torn between offers from Florida and Ohio State, makes his decision based on NIL opportunities? Ohio lawmakers haven’t yet proposed a NIL bill, while Florida’s goes into effect July 1.

“It will be a huge advantage in recruiting,” says Todd Berry, executive director of the American Football Coaches Association.

Berry’s concern lies with boosters. Many state NIL bills don’t bar them from involvement with NIL payments. Some of the bills don’t even address boosters at all.

“You can’t control the boosters,” Berry says. “When you give them openings, based on my experiences, they become uncontrollable.”

For now, the sparring is between lawmakers from neighboring states, competing to adopt the most athlete-friendly legislation the quickest. Many are consulting with their state schools’ athletic directors, in some cases conglomerating ideas and incorporating them into legislation.

“I find myself reading more legislative bills than I ever have in my career,” Texas A&M AD Ross Bjork says. “That’s the time we’re in. We’re past the stage of ‘Is this going to happen?’ It’s happening.”

In the SEC, the paranoia is always high among athletic administrators and coaches. That feeling has now trickled to state capitol buildings in the South.

“I’m looking over my shoulder,” says one legislative aide in a southern state. “I don’t want Alabama to have a competitive advantage over us. What’s legal in Alabama may not be legal in Mississippi but could be legal in Arkansas.”

SEC commissioner Greg Sankey predicted such jockeying among the 11 states in his footprint last summer during a hearing on Capitol Hill. Citing Florida’s law, Sankey told senators, “I can foresee quickly the other 10 one-upping each other.”

And now, here we are.

The race to July is real. States that have already passed laws are working to move up their effective date. In New Jersey, for instance, Democratic Sen. Joseph Lagana has heard from college athletes within his own state, namely Rutgers, who are encouraging him and other lawmakers to move the state’s effective date from 2025 to this July.

“The law was intended to get the NCAA to act, and since they’re not doing so, we need to move up the date,” says Lagana, himself a former football player at Fordham.

Meanwhile, other states are moving toward adopting legislation. This week in New Mexico, a NIL bill breezed through its first legislative step, passing unanimously in a House committee.

“It’s rolling,” says Mark Moores, the Republican sponsor of the bill and himself a former New Mexico football player. “One more committee and then it hits the floor (for a vote).”

Moores has been working on the legislation since California passed its groundbreaking NIL law in 2019, a bill that sparked this wave of historic change. For the last several months, he’s been refining the bill’s language with help from Ramogi Huma, the president of the National College Players Association. Huma, one of the most outspoken NCAA critics, has assisted multiple state governments in creating universal language for their NIL laws, crafting them to avoid NCAA litigation.

“In NIL, the primary powers are going to be the states,” says Huma. “At the end of the day, schools are going to have to comply with their state laws.”

Indeed, states across the nation are racing to the finish line. Down the stretch they come, all in an effort to keep their state schools from losing an edge.

“All of our universities are recognizing that if surrounding states pass it, it gives a leg up on the universities in those states,” says Bounds, the Mississippi lawmaker. “If Mississippi doesn’t act, we will be at a competitive disadvantage.”