The Big Dance Creates Mayhem for More Than Just Fans

Full Frame is Sports Illustrated's exclusive newsletter for subscribers. Coming to your inbox weekly, it highlights the stories and personalities behind some of SI's historic photography.

If you missed last week's edition on Michael Phelps, you can find it here. To see even more from SI's photographers, follow @sifullframe on Instagram.

Also, SI is now offering Morning Madness, a new daily email covering the NCAA basketball tournaments. You can sign up here.

March Madness—the pinnacle of college basketball. While the NCAA basketball tournaments keep fans on the edges of their seats thanks to buzzer beaters and bracket-busting upsets, a similar type of mayhem is happening along the edges of the court and in the rafters as photographers try to capture their perfect shots.

Sports Illustrated contributing photographer Greg Nelson has covered the NCAA men’s tournament since the late 1990s, back when photographers had to use strobe lights and film cameras. The team would include three photographers on average back then, and, due to the size of the project, the group would show up over a week ahead of time to start hanging the strobes.

But when the tournament games started being played in football stadiums, it presented challenges.

“If it was a dome stadium, like the RCA Dome in Indianapolis or the dome in Minneapolis, the dome in Seattle, those domes did not have a catwalk because they were just like a dome that was inflated. It was like an air chamber, essentially,” says Nelson, who was one of the people who helped set up the lights back then. “So the roof was real lightweight, and they didn't have any infrastructure, like girders or anything. And so consequently, we had to put the lights on like big construction lifts.”

Albeit late to the game, Sports Illustrated switched over to digital in February 2003, and Nelson remembers setting up the remote cameras around the court. Now, with a single button he controls cameras scattered around the floor and venue, covering eight different angles, according to photographer Erick W. Rasco. Nelson also uses a handheld camera and one at his feet. Plus, there’s typically one other photographer doing the same thing from the other end of the court at big events like the Final Four and national title game.

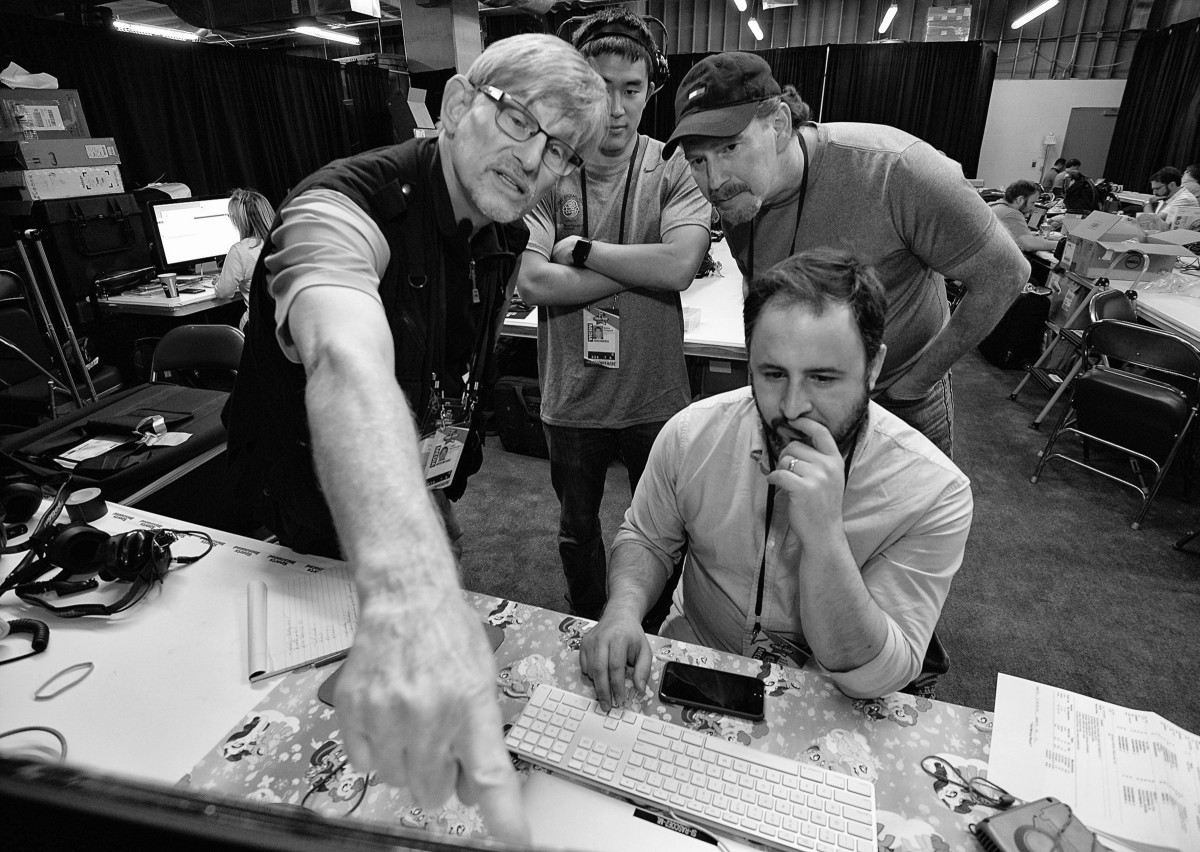

Meanwhile, Rasco works as a producer, editor and transmitter, filtering through the thousands of images coming in live. He edits a few thousand frames before sending them to the New York office. But, some of the cameras store the photos on SD memory cards instead of wiring the photos back to Rasco, which means someone has to run the cards back to be edited.

It takes a village to pull it off.

“There's so much happening that when it's all said and done, I'm just thankful it all worked, and we do what we're supposed to do,” Rasco says. “And we got the magazine out, and we got a cover. And, you know, we fed social, we fed video, we fed web, we've done our part. I don't think people realize what a monstrous undertaking is, and it's a team. I mean, it's not one photographer going out and doing that. Sometimes it is, but for the big event setups, it's a group of people working nonstop for days to make things happen.”

Out of the tens of thousands of photos Nelson will take, he’s keeping an eye out for action shots. And during the 2016 men’s NCAA championship, he snagged his golden ticket of the biggest shot of the year.

The national title game between North Carolina and Villanova came down to the final seconds. Tied at 74, the Wildcats had to get down the court in just 4.7 seconds. The ball left Kris Jenkins’s hands with less than a second to go as he lofted a three-pointer, handing Villanova its second NCAA championship.

Nelson was nestled on the opposite end of the court and decided to shoot wider than he typically would down court, capturing the clock in the background and the emotions of the Tar Heels and fans as they realized what happened.

“My main concern is, ‘O.K., don't miss the shot,’ ” Nelson says. “Because all sorts of things come into play when you're shooting sports, and sometimes you don't have a clear shot. A guy might be obstructed by another player, but in that particular case, it wasn't and that's a good thing.”

At the end of it all, Nelson says, “it’s all kind of luck, really.”

Have questions, comments, or feedback about Sports Illustrated's newsletters? Send a note to josh.rosenblat@si.com.