Brackets, Buzzer Beaters and Burning Jockstraps: For Indiana, Hosting March Madness Renews an Epic Tradition of Hoosier Hysteria

There was bourbon at the first Indiana high school basketball tournament. Bourbon in the locker room. At halftime. Imbibed by the players from Morristown High School.

So said Brainard Nelson, a member of the 1911 Morristown team that lost its opening-round game of the 12-team tourney to Walton, 31–23. Seventy years later, as the last surviving member of that team, Nelson told Indiana Sports Weekly that Morristown was good enough to win that first state title—if only some of the boys hadn’t gotten drunk at halftime. A player smuggled the bottle into the locker room in his bag, and it was empty by the time Morristown returned to the court for the second half. “They were real playful, and even fell down a few times,” Nelson said of his teammates, according to the Weekly. “But, they were having a good time, I guess.”

Shots flew over the backboard, Nelson recalled. Morristown's coach “knew what was going on,” but with only six men available—Nelson was the lone substitute—he couldn’t remove multiple inebriated players.

After emerging sober and victorious, Walton fell the next morning to Crawfordsville, which went on to win the championship that night. “We should have won it,” Nelson said. “We had as good a team as there was there.”

That was not the only drama in that untamed tourney. Rochester lost its best player to ineligibility because he was already enrolled in college at Notre Dame. And then there were Crawfordsville’s hot pants.

Ahead of the title game, the team noticed a trunk holding its uniforms and equipment had been moved and opened. Crawfordsville coach David Glascock, recounting the episode in a letter years later, didn’t think much of it until his team ended the first half with a 13–7 lead and some physical discomfort in sensitive areas. “When the team came into the dressing room at the end of the half, all were on fire and could not stand still,” Glascock wrote. “Some of the boys took off their pants and fanned their legs. It was then that we realized that their Jock straps [sic] had been saturated with Sloans hot stuff [a liniment]. The boys went back into the second half and played like demons. I have always felt grateful to Sloan and his hot stuff for I believe it helped us to win the championship.”

This was three years before World War I, 18 years before the stock market crash, 28 years before the first NCAA tournament. It was 110 years before right now, and what will be the most unique Big Dance of them all.

Sixty-eight college basketball teams have converged in Indiana this week for the NCAA men's tournament. It is an unprecedented condensing of a nationwide tourney, an audacious attempt at pulling off March Madness in pandemic times, a logistical leap of faith and hope.

They’ve come to the right place. The only place, really. This is the state that will embrace the madness and suffuse it with gladness, pouring all of its hoops-loving soul into these three weeks and doing whatever is necessary to see it through to the playing of “One Shining Moment” and crowning of a champion on April 5.

They know the drill here. They’ve seen some stuff. You think 67 games in 18 days is crazy? They've had a tournament here with 36 games (plus a forfeit) in two days. They’ve had a tournament start out with 799 eligible schools and distill it to one.

This is the state that invented and perfected the grand basketball tournament (and then ruined it). Hoosier Hysteria was the first, it was the biggest and it was the best. For more than a century—dating back to the days of drunk teams and burning jockstraps—Indiana has been America’s true Bracketville.

Part I: The Fertile Crescent

Drive northwest out of Indianapolis. Past Brownsburg, hometown of Gordon Hayward, launcher of the most memorable miss in NCAA tourney history. Past Lebanon, hometown of Rick Mount, who landed on the cover of Sports Illustrated in the 1960s as a high school sharpshooter. Past miles of flat farmland, planting season just arriving, the harvest months away.

The horizon stretches to eternity here as the road takes you backward, to the dawn of tournament time. To an exit off I-74, and five miles down Indiana Highway 25, past Ballistic Bart’s Guns. You come to a tiny town and a curve in the road, and you see the sign.

WELCOME TO WINGATE. STATE BASKETBALL CHAMPS, 1913-14.

These are the cultural markers in Indiana—the signs outside small towns and big-city limits commemorating flashes of basketball glory, no matter how old. In a state that played single-class basketball and crowned a single champion for 86 years, there was no greater path to community immortality than winning championships in March. In some places, they celebrated a sectional title. In others, a regional. Fewer win a semistate, and fewer still have been able to say they were the champions of all Indiana.

In Wingate, a dot on the map where eight United States flags snap in the wind on the quiet main drag, they remember the first repeat champs, dating back to shortly after the birth of basketball.

A three-county swath of western Indiana—Montgomery, Tippecanoe and Boone—was the hoops version of the land between the Tigris and Euphrates, the cradle of basketball civilization. James Naismith invented the game in Massachusetts in 1891, but its first great growth spurt was here. (In 1936 after witnessing his first Hoosier state high school tournament, Naismith said, “Basketball really had its beginning in Indiana, which remains today the center of the sport.”) The first game was played in the YMCA at Crawfordsville in the early 1890s, and the area produced the first eight state high school champions. Crawfordsville and Lebanon, 25 miles apart, won the initial state titles in 1911 and ’12.

The tournaments that turned Hoosier Hysteria into a phenomenon, though, were years three and four. That is why you come to the curve in the road, some 20 miles northwest of Crawfordsville and 30 miles east of the Illinois border, to see the sign. There are actually two of them, at each end of town, just to make sure everyone passing through knows Wingate’s faded claim to fame.

The school is long gone in this no-stoplight community of about 265 people—roughly 200 fewer than when the Spartans were winning state titles. But they still remember the Spartan teams that won back-to-back titles four months before the start of World War I.

The world knows the small-town, small-school, underdog story of Milan and its 1954 state championship, which was repurposed as Hickory in the iconic movie Hoosiers. (We’ll get to that in a bit.) But the original Hickory High was Wingate some four decades earlier—a school of 67 students in 1913, just 22 of them boys.

There were no Wingate home games back then because there was no Wingate gym. They conducted limited practices in a school basement or, when the weather permitted, on an outdoor court. “Home” games were played six miles away in New Richmond, and the players often walked the railroad tracks between the towns.

In 1913 Wingate was one of 37 teams invited to Indiana University to play for the title, as the field more than tripled in size. Lightly regarded because of a schedule peppered with other small schools, few people expected Wingate to be around for long.

Yet the Spartans won twice on Friday and three more times on Saturday, defeating big-city South Bend by a point in overtime in the state championship game.

“Although outclassed in teamwork, the husky Wingate quintet fought hard until the final whistle blew,” said the Indiana High School Athletic Association recap. “Stonebraker, the big center, was in the game for blood and was responsible for a large number of the scores made by this team.”

That would be Homer Stonebraker, known as “Stoney,” a Bunyanesque character who was the first big star of Hoosier Hysteria. A latecomer to the sport, he spent hours shooting a rubber ball on a smaller-than-regulation hoop he fashioned at the family farm. There are stories, perhaps apocryphal, about him shoveling a walking path through the snow all the way to New Richmond so Wingate could practice.

In the early days when a jump ball was contested after every basket, having a tall player with leaping ability was the key to everything. Winning the tip and controlling the ball for long stretches of time often dictated the outcome of games. Stoney, reportedly 6' 4", could win jump balls, and he could score. He had 80 points in one game, and according to oral history, possessed an uncanny shooting range.

With Stoney and other key players returning after their 1913 title, expectations were high the following season. Wingate arrived in Bloomington for a state tourney that had doubled in size from the previous season, up to 75 teams. Games were held in four different gyms on the IU campus, with tip-offs scheduled every hour from 7 a.m. to 9 p.m. on Friday and 7 a.m. to 8 p.m. on Saturday. Playing a grueling seven games in two days, Wingate repeated as champions. Stoney scored the first 20 of his team’s points in a title-game rout of Anderson but collapsed near the end and later said he had two broken fingers and three broken ribs.

Now a statewide sensation, Wingate was hailed as an exemplar of virtuous rural living. The Bloomington Evening World lauded Wingate’s victory as “a tribute to the country and the small town. A corn-fed youngster who goes to bed with the chickens and gets up before day has an advantage over the ‘city-feller’ and his cigarette.” Indiana Governor Samuel Ralston and his wife watched several of their games in person and invited the team to the capital. “You boys have become champions and are able to display great endurance because you laid the foundation by leading the right sort of life,” Ralston told the team.

But as the tournament grew, so did the misgivings in some corners. “The practice of developing one team of trained specialists for the high school cannot be successfully defended on any ground,” wrote outgoing IHSAA president Isaac Neff in 1912. “The members of the team are usually over-training from the standpoint of hygiene, and the hero worship accorded them is not in proportion to the intrinsic value of their achievement. It creates an erroneous standard of values.”

Those qualms were quashed in the court of public opinion. Hoosier Hysteria was here to stay and getting bigger every year—so large that the tournament expanded to the multilayered format it still employs today, with sectionals, regionals and semistates preceding the state finals.

In 1921 the tournament moved to the Indianapolis Coliseum, where it was played in front of 7,200 fans. In 1927 the competition started with 731 teams in pursuit of the single title, which was won by a Martinsville team paced by a ferociously competitive guard named John Wooden.

The following year, Wooden and Martinsville tried to defend their title in a new arena, the largest gym in America. Butler Fieldhouse held 15,000 fans, but it wasn’t built to that massive scale for the Butler Bulldogs college team. It was built that large to host the Indiana high school tournament finals.

Part II: The Forgotten Pioneer

Joe Morris is a ball of energy and big ideas, a man returned to his hometown with grand plans. The Washington High School alum moved back from Indianapolis last year to take two jobs: football coach of the Hatchets and executive director of Daviess County Chamber of Commerce and Visitors Bureau.

Among his big ideas: the Big Dave Basketball Tournament. “We can bring so many people here to learn about his story,” Morris says.

The tournament Morris envisions would draw teams from around the nation to honor the racial pioneer nobody knows about, a player whose exploits broke barriers but largely faded away without lasting commemoration. The black-and-white photographs from the time are crude but arresting: a Black player soaring above his white teammates and competitors for a rebound; palming a basketball and holding it out in front of him; standing at the end of a scowling line of Washington Hatchets, taller than all the rest. That’s Big Dave DeJernett.

From 1929 to 1931, he was the powerful, explosive center who led Washington to three state finals appearances, winning it all in 1930. DeJernett was a racial outlier in the southwest part of the state, coming from a county that was 0.7% Black in the 1930 census. A star Black basketball player in the late 1920s might not have stood out quite as much in New York or Chicago; in Washington, Ind., it was a startling sight.

That was underscored by the prominence of the Ku Klux Klan in Indiana in the 1920s. In 1922 they held “Klan Day” at the Indiana State Fair. By 1924 Klan-backed politicians had taken control of the state government. The Indiana Klan of those days was mostly devoted to anti-Catholic fervor, but the hate group would eventually threaten Big Dave.

How did Dave DeJernett end up becoming a Black hero in a white town? It began with a flood, a railroad disaster and a call for help. In March 1913 after torrential rains led to flooding across southern Ohio and Indiana, the B&O Railroad tracks outside of Washington collapsed and four men were killed. B&O put out a call for track repairmen, and John DeJernett moved with his wife and young children from Garfield, Ky., to work.

Washington had a small Black population dating back to the early 1800s, according to the Daviess County History Museum, and there is evidence that the town had established safe houses on the Underground Railroad. A photo at Washington High School today shows an integrated 1914 state championship track team, but no Blacks had played basketball for the Hatchets before Big Dave and Harold Bledsoe joined the team in 1928–29, according to Daviess County research material. The school yearbook from 1930 contained pictures of nine Black students interspersed among a few hundred white faces.

The Hatchets’ new coach, Burl Friddle, had been a member of the Franklin “Wonder Five” that won three straight state titles from 1920 to 1922. Friddle recognized that DeJernett, though inexperienced, could control the jump balls after every basket. His height, listed as anywhere from 6' 2" to 6' 5", was augmented by his leaping ability and large hands. Eventually, Big Dave’s skill level caught up to his athleticism and he became a dominant force—with many newspaper articles at the time including the modifier “colored” or “Negro.”

The 1930 championship game, with 15,000 crammed into Butler Fieldhouse and many more listening to the radio broadcast, presented a glimpse of basketball’s future.

Big Dave matched up with 6' 6" Muncie center Jack Mann, also Black, in an epic battle of big men. Mann used his height advantage to control the majority of jump balls, and Muncie took a halftime lead. Friddle told DeJernett that they needed him to take over to win, and Big Dave responded by winning a majority of the jumps the rest of the way. Washington won its first state title, 32–21, with DeJernett scoring a game-high 11 points and becoming the first Black player on an Indiana state basketball champion.

The prose of the times was hyperbolic. One story on the game began: “Not since Columbus discovered America and Washington crossed the Delaware has a greater struggle been fought and won than the triumph of the Washington High School in the nineteenth annual championship of the Indiana High School Athletic Association.” But, in fact, the state that loved the game the most saw a vision of how it could be played best—by letting everyone compete.

Basketball, though, did not beget equality. Dave Spillman, longtime P.A. voice for Washington games at the fabled, 7,090-seat Hatchet House, said stories were handed down about restaurants serving meals to Black Washington players on paper plates while their white teammates ate on porcelain.

With Washington attempting a repeat title bid in 1931, the Klan came calling for Big Dave. Before playing Vincennes in the regional, DeJernett received a letter signed by the “Committee of 14, KKK,” threatening him if he “so much as touched” a white player during the game. The note cited the lynching of two Black men in Marion, Ind., the previous year. DeJernett took the letter to school, and word of it eventually leaked to the Evansville Courier.

In a book written by Big Dave’s sister, Kay Granger, she said her brother didn’t take the letter very seriously. Other reports say DeJernett’s father attended the game with a pistol in his pocket. Regardless, Big Dave scored a game-high 14 points—which the Washington Herald gleefully noted was “one point for each of the ‘committee of 14’ which signed the cowardly letter which Dave received."

DeJernett again met Jack Mann in the state quarterfinals, and this time Mann prevailed. Muncie went on to win the state title, and both pioneering big men went on to play college basketball—Mann at Wilberforce in Ohio, DeJernett at Indiana Central College. They both played professionally in Chicago, and Big Dave also played for the New York Rens before joining the Army in World War II.

DeJernett served as a sergeant in both the North African and European theaters, earning four bronze battle stars. Life after the war was not easy; DeJernett moved to Indianapolis and was twice convicted of DUI. He died of a heart attack in 1964—remembered by some, but not by enough.

Part III: The Apex

Sixteen right-handed dribbles and one pull-up jump shot. That was Bobby Plump’s final path to immortality, and it marked the highest point of Hoosier Hysteria.

The Hoosiers version of Milan’s 1954 miracle state title omits much of the monotony of Plump standing still holding the ball for up to four minutes at a time in the second half against Muncie Central. But after losing a nine-point lead, coach Marvin Wood figured that shrinking the game to just a few possessions was his team’s best chance to win. Milan even stalled while trailing, 28–26, in the fourth quarter.

When Milan finally got back to playing ball, Plump missed a long shot and Muncie had a chance to take control. But after a turnover, Milan’s Ray Craft—the kid who milked cows on the family farm daily before school—made a jump shot to tie it at 28. Plump then added two free throws 26 seconds later for the lead, but Muncie scored to tie it at 30 with 35 seconds left.

Following a Milan timeout with 18 seconds left, Wood put everything in Plump’s hands. After dribbling sharply in place for most of that time, Plump accelerated forward to the elbow of the key with four bounces before lifting and firing the most famous shot in Indiana history—one of the most famous in basketball history. Plump’s shot was one of the original game-winners kids grew up replicating in their driveways.

A tourney that started with 751 schools ended with one of the smallest—enrollment of 161, from a community of fewer than 1,200—winning the title.

Fifteen thousand watched it live in Butler Fieldhouse, and the Indianapolis Star estimated 2.5 million more listened to a radio broadcast that was played on every station in the state and several neighboring states. There were an estimated 250 newspaper writers in attendance. This was the most celebrated game in Butler Fieldhouse history, far bigger than the 1940 national semifinal Indiana University won on the way to capturing the NCAA tournament championship in Kansas City.

But the team that won the state tourney the following two years was almost certainly better, and resonated nationally in its own way. That was Indianapolis’s Crispus Attucks, led by the greatest Hoosier high school star of them all, Oscar Robertson. (Larry Bird went on to collegiate and professional greatness that surpassed Robertson’s. But at Springs Valley High School he was truly just the Hick from French Lick until a growth spurt before his senior year transformed him.)

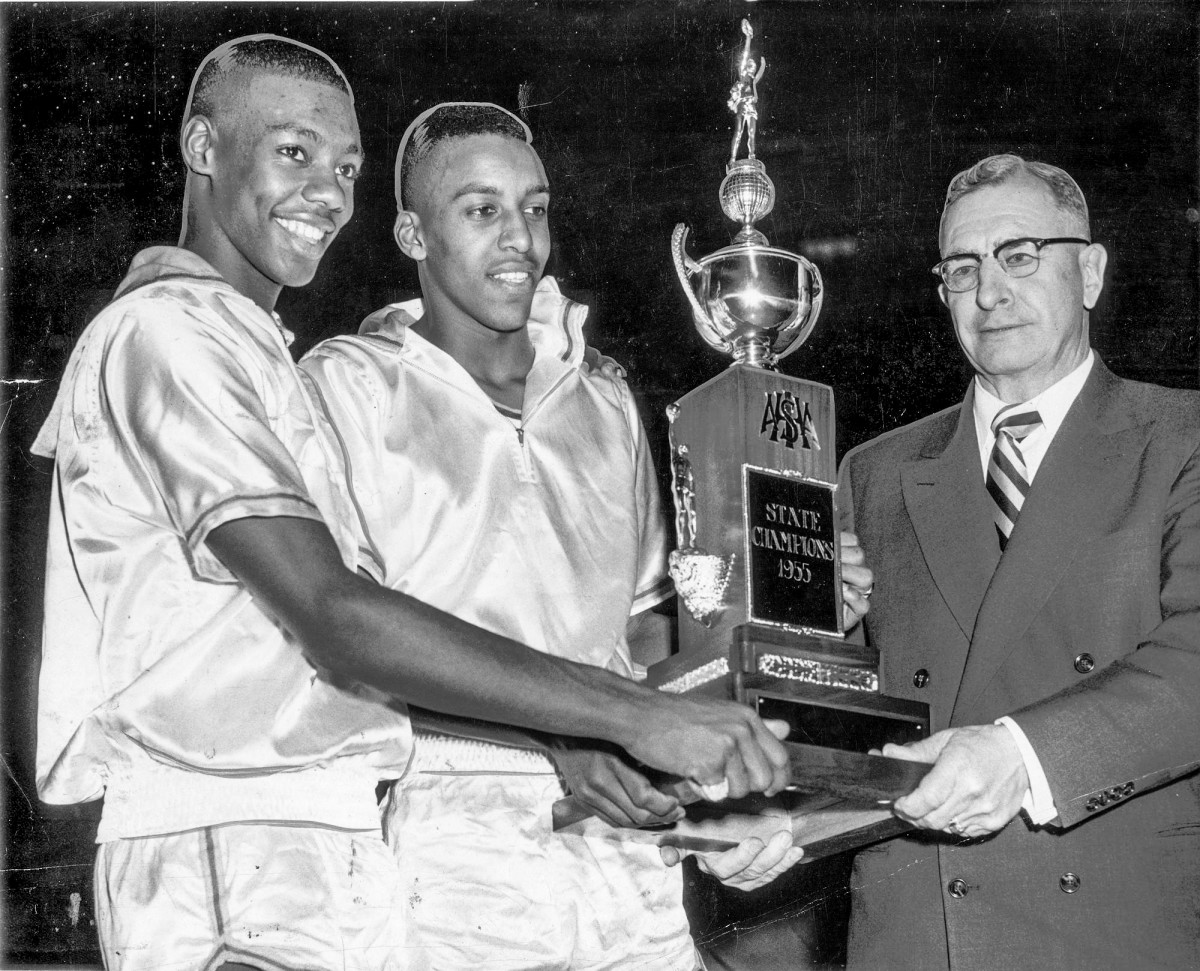

In 1955 Attucks (30–1) defeated Gary Roosevelt in the first matchup of all-Black teams, 11 years before Texas Western became college basketball’s first champion with an all-Black starting five. After the stall ball of the previous title game, this was a fast-paced thrill ride: Attucks won 97–74, a record number of points in a championship game that still stands. Robertson scored 30 of them.

Stunningly, this was the first state championship for an Indianapolis school. But the Tigers never got the feeling that the entire city celebrated with them.

The postgame victory parade wound through downtown Indy, but it didn’t include any stops at Monument Circle or other landmarks before veering to the Black side of town. That upset some of those associated with Attucks, who suspected the powers that be wanted them out of downtown as quickly as possible and back into their segregated area.

“The parade was the shame of the city,” former Indianapolis Star writer Bob Collins told Indianapolis Monthly years later. “It was just a lack of feeling and understanding. Whites thought it would be nice to give blacks a parade through their own neighborhood, so they could celebrate. There was a total white misunderstanding of the blacks. That in itself is a form of prejudice.”

Robertson’s father, Henry, told the magazine that his son said, “Dad, they really don’t want us.”

It certainly stands as a contrast to Milan’s victory parade the day after the title a year earlier. Fans lined State Road 101 for 13 miles leading into town, with an estimated 40,000 people descending on the small burgh in the southeast corner of the state. The team returned from Indy in a line of Cadillacs, finishing the drive with the state trophy and two players sitting on the hood of one of the cars. Players disembarked at the high school, nets around necks, letter jackets on, kings of Indiana.

Hoosier Hysteria would never get better than those back-to-back championships in the mid-1950s. But it would, somehow, get bigger.

Part IV: The Last Hurrah

Damon Bailey is choking up on the phone. The most celebrated of all Hoosier schoolboys is driving from his Indiana home to Wichita, en route to see his son, Brayton, play in the NAIA national championships for the University of Saint Francis. Brayton is a freshman guard on the team, the second of Damon’s kids to play college ball after his daughter, Alexa, played at Butler and Indianapolis.

If you’re of a certain age, here’s the next slap in the face from Father Time: Damon is going to be a grandfather in September.

But that’s not why he’s choking up on the phone. We’re talking about the 1990 state championship game, biggest of them all, the coda Bailey’s incomprehensible career not just deserved but demanded. The game that put 41,046 people in the Hoosier Dome—yes, 41,000. The game that ended with Bailey scoring the final 11 points for Bedford North Lawrence, leading a scrambling comeback to hand Concord High from Elkhart its only defeat of the season.

Sign Up to Play SI's Bracket Challenge and Compete For a Chance to Win Prizes.

Create Your Group Now | Official Rules

But that’s not why he’s choking up, either. Damon Bailey is choking up because I asked him about what he did right after briefly celebrating with his teammates when the game was won.

“It wasn’t anything I had planned, but something for me just clicked,” Bailey is saying, his voice thickening. “I thought, ‘Hey, there’s two people I need to go thank.’ ”

Those people were his mom and dad, Beverly and Wendell. Damon went climbing into the stands and enveloped them in an embrace tinged with sweat and tears. And now there are tears anew, as Bailey relives that moment.

Wendell Bailey was killed in September in a motorcycle crash in Brown County, Ind. Beverly Bailey was injured.

Wendell Bailey was an old-school, tough-love dad, reticent to sing his prodigy son’s praises in public. When John Feinstein’s seminal book on Bob Knight and Indiana’s 1985–86 team, A Season on the Brink, shone a tangential spotlight on the star eighth-grader at Shawswick Junior High, Wendell’s response was that Damon had better work hard enough to back up the hype.

“When Coach Knight came and watched me at Shawswick, things changed,” Damon says. “The attention just became part of my life. I thank the Lord every day that social media wasn’t around when I was growing up.”

Damon responded to the adulation by pushing himself to become the leading scorer in Indiana high school history, and its leading folk hero. While reporting a story on him in 1990, he told me he rose before dawn every day and jogged from his house in tiny Heltonville to his old elementary school to shoot 500 shots. I popped in on him unannounced at the school one morning and found Damon helping the janitor sweep the hallways—he’d already gotten up his shots.

He was the complete Indiana schoolboy package. And the state ate it up.

He filled gyms—huge gyms—around the state. It was the draw of Damon that led the IHSAA to make the ultimate power move, taking high school basketball into a football stadium. “The first day of practice, coach [Dan] Bush came in wearing a Hoosier Dome shirt and made the announcement,” Damon recalls. “He said he fully expected us to be playing there.”

Playing there was expected. Winning there became the quest.

It was a very big deal when Damon led Bedford to the Final Four as a freshman. It was a bigger deal when he did it again as a sophomore. As a junior, BNL was taken down in the regional round. His senior year, the team felt an imperative to win it all.

The BNL Stars were so close to fulfilling the quest … and then it appeared to be slipping away in the championship against Concord, down six with 2:38 left. But Bailey kept driving the ball and scoring, on his way to 30 points for the game. Concord had three final three-point attempts to tie in the closing seconds, and none of them connected.

“They were all pretty good looks,” Damon recalls. “We just couldn’t get the rebound. It seemed like those nine or 10 seconds lasted a lifetime. To finally reach that pinnacle after fighting so hard, it was special.”

Thus the storybook career reached the appropriate ending, in front of the largest crowd to ever see a high-school basketball game. The following season, Purdue mega-recruit Glenn Robinson met Indiana mega-recruit Alan Henderson in the title game, and they put 30,345 fans in the Dome—a phenomenal number but a dramatic decrease year over year. Attendance would never again approach those two crowds for a single game.

By 1996 the IHSAA was ready to dilute its perfect product. It voted in multiclass basketball, starting with the 1997–98 season, ensuring that there would never be another Wingate or another Milan. The ultimate underdog stories were dead, the scope of the accomplishment diminished. Handing out more hardware simultaneously cheapened the hardware, as Indiana basketball lost the allure of crowning a single champion.

Damon Bailey’s title run, with Robinson and Henderson riding his folkloric coattails a year later, would prove to be the last hurrah for the state’s outsize interest in high school basketball.

This week, though, they’ll conjure some of the old hysteria. They’ll even return to some of the sacred settings, a fitting callback to the heritage of the sport. They’re awakening ancient echoes at Indiana and Purdue, which combined to host 13 state tournaments; at Indiana Farmers Coliseum, which hosted three IHSAA finals during World War II; and, of course, at the Hinkle cathedral, formerly the Butler Fieldhouse, one of the centerpiece NCAA venues after serving as a high-school mecca for decades.

The fans will not be crammed in cheek-to-jowl like the old days, of course. And Purdue is the only team from Indiana that was invited to this Dance, while the rest of the state licks its hardwood wounds. The local fervor largely will be directed toward the event itself, toward the glorious drama of tournament basketball and the brackets that give it shape, toward the game that became a way of life here.

Sixty-eight teams, 67 games, one state, let’s go. Indiana is ready and willing. It has danced this dance many times before.

SI’s tournament newsletter analyzes everything you need to know about the Big Dance: what just happened and what’s happening next. Sign up for Morning Madness here.