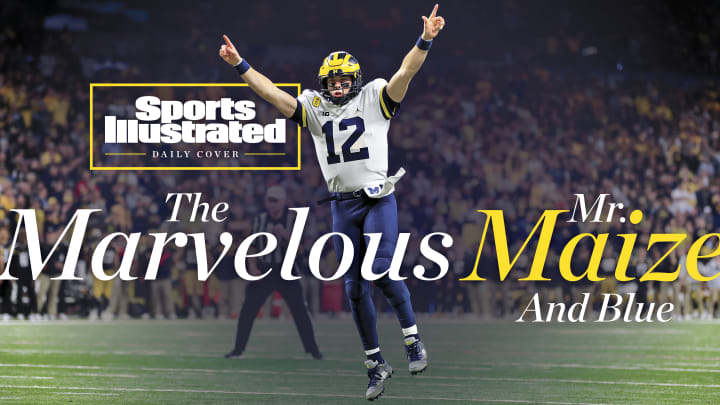

You May Not Believe in Cade McNamara. But He Does. And That’s Enough.

Fewer than 10 minutes after hearing on Sunday that his team was the No. 2 seed in the College Football Playoff, Michigan quarterback Cade McNamara went to watch film by himself. Whether he needed to do this depends on how you define the word need. No coach asked him to do it. The Wolverines’ CFP semifinal against Georgia was 26 days away. But McNamara says, “I couldn’t imagine going back to my apartment not having watched film. It would make me sick to my stomach.”

You can tell the story of Michigan’s first CFP berth a few ways. Jim Harbaugh shuffled his staff and led a team that went 2–4 in Strange COVID-19 Times to a Big Ten championship. Defensive end Aidan Hutchinson, the son of a former Michigan All-American, played like a Heisman Trophy candidate. The whole team vowed to finally beat Ohio State—and then did it, thanks largely to an offensive line that physically dominated the Buckeyes.

But maybe the best way to understand how the Wolverines got here is to look at who led them. McNamara epitomizes his team as well as anyone in the country: “A very stubborn human being,” says his father, Gary, on a team full of very stubborn human beings. Cade always believed but never assumed. He is constantly trying to prove doubters wrong, but he never makes throws that look like he is trying to prove doubters wrong. He does not force passes. In the past two years, he has thrown 379 passes and only four interceptions. He has never committed two turnovers in a game.

McNamara is not the most physically talented quarterback in the Playoff. He is not even the most physically talented quarterback on his own team. He is 6' 1", he does not have overpowering arm strength and he won’t outrun many linebackers. Yet in the past few weeks, when Michigan has trusted him to make big plays, he has delivered, repeatedly.

“I always felt that I had enough,” McNamara says. “I had enough talent. I had enough size. And I just had to use the most out of what I have.”

Of the four quarterbacks in the Playoff, only McNamara is a sure bet to get yanked from a game. Harbaugh does it almost every week. Out goes McNamara, in comes freshman J.J. McCarthy. Hutchinson says, “I still don't understand the rotation”—but the logic is actually pretty clear. McCarthy, a former five-star recruit, is better at designed runs or option plays where he can take off, and he is still a threat to throw, and so he gives Michigan a dynamic that McNamara does not. “As McNamara puts it: “[It’s] not that I'm a bad runner. J.J. is just more talented at running.”

This sounds like a nice story about a humble junior willingly sharing time with a freshman, but that’s not quite it. McNamara doesn’t want to share time. He just wants to be a leader, and leaders do not complain when they share time.

“I think the way I handle this situation will affect the team,” McNamara says. “I have to do my best to put myself in the mindset that what [I do] is help the team win. And if J.J. is on the field for a couple plays, he's only making the field shorter for me.”

In his first year on campus, in 2019, while he was redshirting, McNamara told his dad he wanted to be “the best leader that’s ever been here,” and then he went into detail about all the ways he could help the players improve their program.

“All these kids want to play,” Gary says. “He wanted to play because playing meant I get to lead now.”

Leading, that nebulous and often-misused term, is the essence of McNamara. It means believing but never being overconfident, helping teammates but not coddling them and being honest about himself but still expecting greatness. McNamara has an acute awareness of his own limitations and a firm belief that they should not hold him back. This can make him a hard book to read. Some of the stories seem contradictory, but they fit together if you look at them the right way.

Gary says his son believes he has “never had a good practice.” He and Cade often have this kind of conversation:

Dad: How was practice?

Son: Terrible.

Dad: What happened?

Son: I threw an interception.

Dad: How many throws did you make?

Son: Fifty.

Dad: What about the other 49?

Son: Oh, those were good.

And yet, Gary also says this: “Five years ago, if Bill Belichick would have brought Cade into his office and said, ‘Cade, we just don’t think you’re any good,’ Cade would have walked out of that room and said, ‘Dad, you won’t believe it: Bill Belichick doesn’t know anything about football.’ ”

Cade chose Michigan in part because he knew he wouldn’t start right away—sitting would be good for him. Yet he arrived and immediately saw his low spot on the depth chart as disrespect. By his second year on campus, he was battling Joe Milton for the starting job. Harbaugh chose Milton. Many players in McNamara’s position would have transferred. Cade just told his father he should have gotten the job, he would get his chance and then he would prove it.

“Joe is just about as freakish of an athlete as you can find at the quarterback position,” McNamara says. “And I think, obviously, there's some things that he [can do] in practice that I probably will never be able to do in my life. And that’s O.K. But I mean, that could be one play. What are you doing the other 60 snaps of practice—right?”

McNamara makes it clear that this is not a shot at Milton, whom he calls “an extremely good practice player” (and who transferred to Tennessee in April, after McNamara got a chance and unseated him late last season). He just believes in his own ability to lead, to read defenses, to be consistent, to practice with intensity and to avoid mistakes. He manages, somehow, to see himself as the best in the country while also understanding why others don’t see him that way. He believes he has enough.

There are some obvious parallels between the McNamara-McCarthy partnership of 2021 and the most famous quarterback competition in Michigan history, between Tom Brady and Drew Henson in 1998 and ’99. McCarthy is younger, a more heavily touted recruit and, to any scout’s eye, more physically gifted—just as Henson was. McNamara is a dogged worker who combines an unwavering faith in himself with the understanding that he must support the coaches, whether or not he agrees with their rotation—just as Brady did.

More: The Brady-Henson rotation really cost Michigan, at most, only one game: a 34–31 loss in East Lansing to a Michigan State team that finished 10–2. Henson committed a second-half turnover. Michigan’s only defeat this year was a 37–33 loss in East Lansing to a Michigan State team that finished the regular season 10–2. McCarthy committed a second-half turnover.

McNamara is not Brady. But he shares some important qualities with him. Brady is not fast, but he buys time in the pocket. He does not make many freakishly athletic plays, but he is a master at making whatever play is there. Sometimes McNamara even sounds like Brady: “I think there's more to playing quarterback than being able to throw a football. I think the effect that you have on the offense, the effect that you have on guys … the quarterback has such a bigger influence than just completing passes.”

Brady’s strengths did not fully reveal themselves until he faced big-game pressure. McNamara is the same way, and he knows it: “I think game situations (require) poise. It requires command. And I think you can do your best to replicate that in practice, but there are obviously limitations.”

Like Brady, McNamara remembers the slights and the failures more than the compliments and the triumphs. He will tell you that in his freshman year at Damonte Ranch High, in Nevada, he had to split time with an older player, that it fractured the team, that “fights broke out in the [stands] … parents screaming at me to get off the field.” He remembers “waiting to get picked up by my dad after a game, waiting for him to comfort me. It was very difficult.” He is less likely to mention that he set Nevada state records for passing yards and touchdowns.

He is aware of the narrative that McCarthy is a more talented player; he knows that some people wondered whether he was better suited for a smaller conference, like the Mountain West. He doesn’t point out that Alabama, Notre Dame and USC, among others, offered him scholarships.

Hutchinson says: “On social media, early in the season, everyone wanted him out. And, you know, I don’t think he cares what anybody thinks about him.”

He does care. He just doesn’t complain publicly.

“He has a humongous chip on his shoulder,” his father says. “It is still there today. He feels disrespected. He’ll still talk about those people [from high school]: Those people didn’t want me, and we won a [regional] championship.”

Cade shows that chip in small ways. He marks his territory subtly, like when talking about McCarthy’s package of plays. “Being the quarterback, I know every play that has the potential of being called every single game,” he says. “So I know what plays are his, and the rest of the call sheet’s mine.”

He says he likes McCarthy. Sometimes the two quarterbacks’ families sit together at games. But he is far too competitive to cede turf. “We're teammates,” he says. “That’s about it. I mean, I consider myself a good teammate, and I consider him a good teammate. We don’t hang out that much, but that's fine.”

Brady always believed he was better than Henson, even when he was not clearly superior in any way. He was just absolutely sure that, under duress, he was a winner. He was right, obviously. Asked about the Brady-Henson comparison, Cade says, “I‘m extremely aware of the situation.” He is hoping to talk to Brady about it soon. He will likely find somebody who understands him.

Saturday night, after Michigan beat Iowa to win the Big Ten, McNamara saw his parents. He talked a little about a completion he threw to tight end Luke Schoonmaker, and a lot more about everything that went wrong on his lone interception. Michigan had won the game 42–3, but let’s keep that between us.

More College Football Coverage:

• ‘The Schools Clearly Aren’t in Control’: Inside College Football’s Wild Week

• Blockbuster Moves Headline Wildest Week in CFB History

• Why Playoff Expansion Was Stalled Again

• Brian Kelly’s Brusque Exit at Notre Dame Is Nothing New

Michael Rosenberg is a senior writer for Sports Illustrated, covering any and all sports. He writes columns, profiles and investigative stories and has covered almost every major sporting event. He joined SI in 2012 after working at the Detroit Free Press for 13 years, eight of them as a columnist. Rosenberg is the author of "War As They Knew It: Woody Hayes, Bo Schembechler and America in a Time of Unrest." Several of his stories also have been published in collections of the year's best sportswriting. He is married with three children.

Follow rosenberg_mike