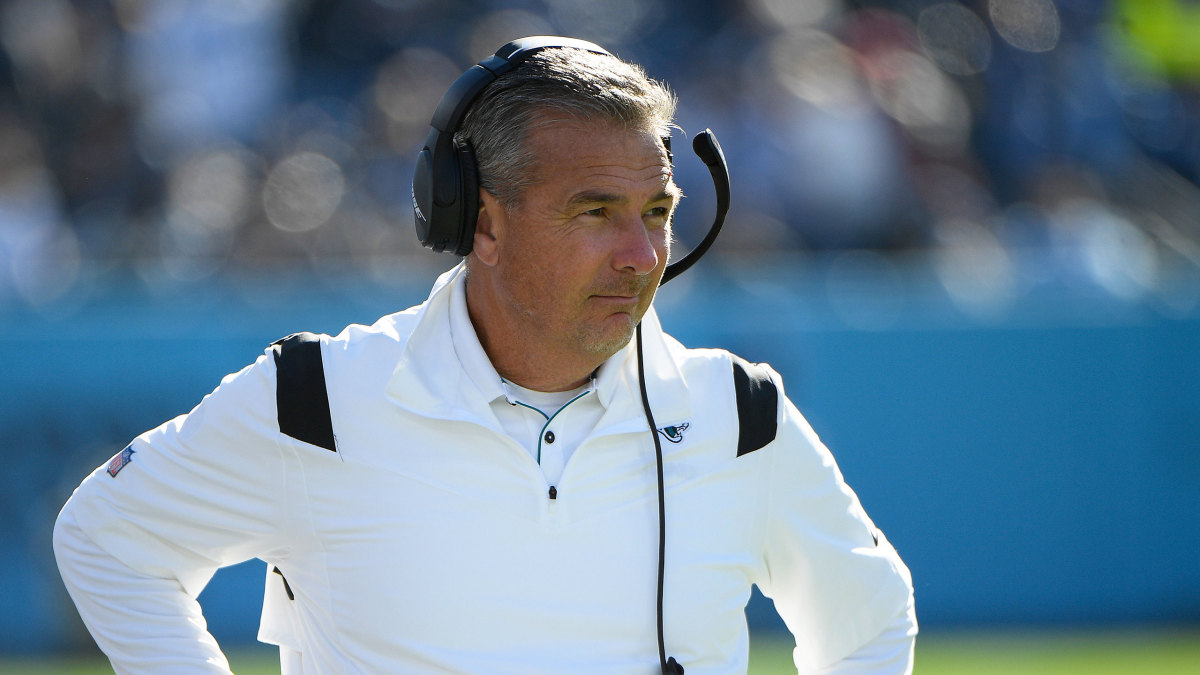

If Urban Meyer Runs Back to College, the Playing Field Will Be Different

The Jaguars have fired Urban Meyer for gross … well, gross everything. He did such a remarkably horrible job that firing him now almost seems too kind. Jacksonville should have made him coach the last four games in a hat with “I GOT FIRED” written on it, then pump static into his headset all afternoon.

The obvious and fair takeaway is that Meyer’s ways don’t work in the pros. But that doesn’t go far enough. So much of what Meyer did this year wouldn’t work in college sports anymore, either.

Yes, Meyer was one of the best college coaches ever, winning three national titles and winning big at four programs. But college sports have changed dramatically since he left Ohio State in 2018.

Players are free to transfer once without penalty now. They can capitalize on their name, image and likeness, a development that will turn some college stars into millionaires and bring them the freedom that money provides. Why should they take abuse from a coach who says he can get them to the NFL, when they can make big money before they get there?

Public opinion has shifted dramatically in favor of players doing whatever they please. Stars skip bowl games to prepare for the draft; a few opted out of the 2020 season entirely, not just because of COVID-19, but also because they wanted to stay healthy and preserve their draft status.

For decades, college athletes in dysfunctional or abusive environments felt trapped: They had to sit out a year if they transferred, and their coach might bad-mouth them on the way out, limiting their options. But now collegians who hate their coach have more power than their professional counterparts. When Jacksonville players lost respect for Meyer, all they could do was laugh behind his back and leak information to reporters. College players can walk out and never come back.

Look through some of Meyer’s biggest mistakes this year, and you can find a comparable example that blew up on a college coach.

He hired Chris Doyle as his director of sports performance despite Doyle’s alleged history of making racist comments and mistreating players. The comp here is, of course, Chris Doyle. Doyle had already lost his job at Iowa for this, and he was unhireable on the Power 5 level.

He was caught on video grinding against a woman, who was not his wife, in a bar. This on its own would probably not get most college coaches fired, but we have seen extramarital misconduct start to push many (Ed Orgeron, Rich Rodriguez, Bobby Petrino) toward the exits.

He reportedly kicked a player (kicker Josh Lambo, who went on the record with the Tampa Bay Times). In the past three years, at least three women’s basketball coaches—Syracuse’s Quentin Hillsman, Florida’s Cam Newbauer and Texas Tech’s Marlene Stollings—got fired for mistreating players.

Toxic culture has become a catch-all phrase, and the comparisons aren’t perfect. But a college coach who acted like Meyer did this year would have lost their team and then their job, just as he did.

When Meyer started coaching, stories of players being mistreated were often ridiculed. A real scandal, critics said, was paying players under the table. Bear Bryant’s players went through much worse. Mindsets have changed for the better. Kick a player now, and he can complain about it on social media and enter the transfer portal by dusk.

College players have more power than they ever had before, and yet they are still just beginning to learn how much. This week, one of the nation’s top football recruits, Travis Hunter, spurned Florida State (and pretty much every other major power) to sign with Jackson State. There is speculation about Hunter getting paid big money by a third party, but whatever the terms, it is no longer a scandal. Hunter doesn’t need to play for one of college sports’ big brands to make him rich or famous. He can do it at Jackson State—and if he is unsatisfied there, Florida State will gladly welcome him.

The new reality makes a lot of people uncomfortable. Clemson coach Dabo Swinney said, “Education is like the last thing now,” a comment that earned him derision but also happens to be true. It’s not about education at all, and of course this should bother administrators. But those administrators should have been bothered many years ago, as they paid millions to college coaches and valued winning and alumni donations over education. They might not like this world, but their misplaced priorities created it.

A young Urban Meyer wouldn’t make it these days, which makes you wonder: Will anyone hire this Urban Meyer?

Meyer looked miserable almost from the start in Jacksonville. It was obvious this fall that he didn’t like his job. But he is also a highly competitive person with an enormous ego who lacks self-awareness, and it must be killing him to go out like this. He has already retired three times only to come back. After this debacle, it seems likely he will want one more shot at coaching college ball so he can write a different ending. If Ohio State’s Ryan Day leaves for the NFL, Meyer-back-to–Ohio State speculation will begin immediately.

Athletic directors and presidents who are tempted by Meyer’s résumé should take a hard look at the years next to the accomplishments. There was a time when Urban Meyer was the best college football coach in the nation. Players compete in a different time now. Can he?

More Urban Meyer Coverage:

• Urban Meyer Never Stopped Living in the Past

• Lambo Explains Why He Shared Meyer Accusation

• Video: Meyer Ended His Own NFL Career