Rick Flick Lost His Son. At Cincinnati, He Found New Purpose.

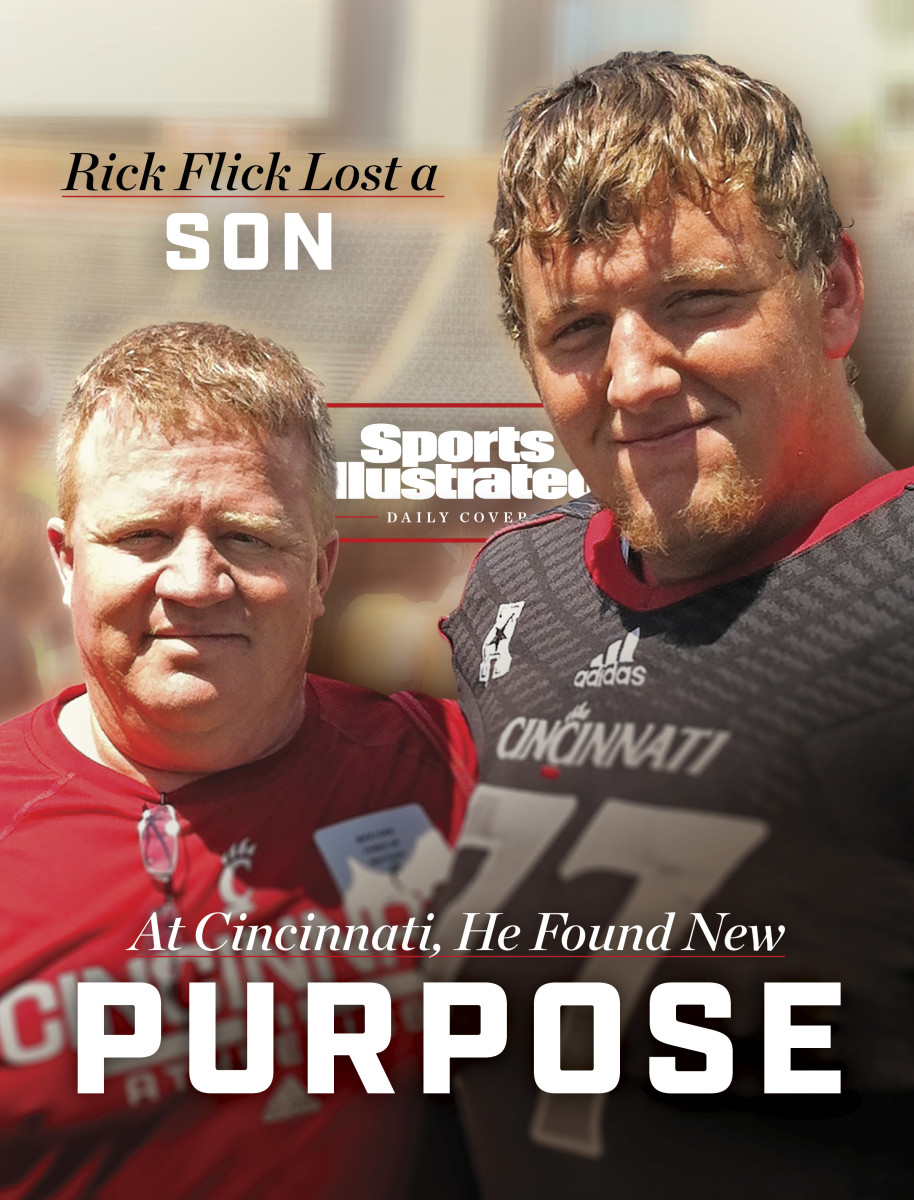

Rick Flick is sitting in a conference room in the University of Cincinnati’s Richard E. Lindner Center, home base for Bearcats athletics. The swivel chair he occupies is pointed halfway toward the glass door and windows, and every few minutes a football staffer slows down his or her hustling gait to smile and wave in Flick’s direction. The 58-year-old returns the greeting, over and over, like homecoming royalty on a parade float.

No one outside the Cincinnati football program knows who Flick is. He’s not listed on any staff directory, he’s never in the spotlight and he doesn’t draw a salary from the school. He’s the CEO of a supply company that sells nuts and bolts and other hardware. But everyone inside the program knows him, and they adore him.

“I don’t know how to explain him,” head coach Luke Fickell says. “I thought he was just a maintenance guy when I first got here, but he is the most unique person. Whenever there is work to be done, Rick’s there. Whether it’s bringing stuff to my house for recruiting weekends, you look up and Rick’s there. Whether it’s fixing something at the facility, Rick’s there. When we need a truck, Rick’s there. I’ve known plenty of people who show up for the party after the work has been done. Rick is there for the work, and he’s usually the first one there and the last to leave.”

“He’s the mortar that fills in the cracks,” says Fickell’s personal assistant, Sherry Murray. “Wherever you need him.”

“Bring in Rick,” says director of football operations John Widecan, “problem solved.”

Every college football program needs a Rick Flick—a game-day handyman, an advance roadie, a stadium operations savant. Not every program has that guy. And likely no program has a guy who attached himself for the reason Flick did.

The backstory begins in a display case a couple of floors down in the Lindner Center. That’s where the plaque resides that recognizes the annual winners of the Ben Flick Memorial Award. It’s given to a freshman from any Cincinnati varsity sport who “exemplifies the qualities of charisma, passion and dedication.”

Ben Flick came to UC in 2013 and never played a down for the Bearcats, his dream cut short on a rural road in Butler County, Ohio. But his impact lives on—in the award, yes, but more so in the form of his father’s unceasing devotion to the program.

“I’m going to fulfill Ben’s four-year commitment,” Rick told himself initially, years ago. And after those four years he kept going, returning to the Bearcats season after season, through a coaching change, offering himself as mortar to fill in the cracks of a program that continues to grow beyond anyone’s wildest dreams, to the point where it will face Alabama in the semifinals of the College Football Playoff this week.

Rick Flick needed Cincinnati football, he realized. It helped him heal a shattered life.

Turns out, Cincinnati football needed him, too.

On the night of Sept. 21, 2013, Rick Flick settled in at his home in Hamilton, Ohio, to watch a little college football on TV. He had attended Cincinnati’s afternoon road victory at nearby Miami (Ohio), the Bearcats improving to 3–1 in coach Tommy Tuberville’s first season. Ben and two other Bearcats freshmen who were also redshirting, and a high school friend of Ben’s who attended Miami, were also at the game.

Rick had met up with the group beforehand, then sat separately. He got home in time to catch Texas A&M star quarterback Johnny Manziel in action against SMU. Around 8 p.m., Ben texted Rick that the group was headed back to Cincinnati. “Be careful,” Rick texted back. “I’ll talk to you later.” Ben replied, “I love you.”

Around 10:30 p.m., Rick started feeling uneasy.

“I don't want to say it’s a premonition, but I had this feeling,” he says. “I can’t explain it. But the only way to describe it, something was wrong. Like something just wasn’t right. It was very strange. But, you know, as a parent …”

Flick went to bed. A couple of hours later, he was awakened by a knock at the front door, and that vague uneasiness quickly morphed into palpable dread. Rick looked out the window and saw a law enforcement officer standing there. “He’s out of central casting,” Rick recalls. “He’s got the windbreaker on, the shirt and tie. It’s like, ‘S---.’”

Flick’s dog was barking, making it difficult to hear what the officer was saying, but the details didn’t matter. Rick knew why he was there.

A black Chevy that Ben had been riding in careened off Stahlbehner Road near the intersection with Morman Road in Hanover Township. The four passengers were returning from the Cincinnati-Miami game. Ben was in the front passenger seat. His high school friend, Sean Van Dyne, was driving. Ben’s teammates, Mark Barr and Javon Harrison, were in the back. Only the two in the backseat were wearing seat belts. Police estimate the car was going 85 mph five seconds before crashing. A nearby resident found it upside down and called 911. The front-seat passengers were ejected.

Flick was pronounced dead at the scene. Van Dyne died two days later from his injuries. Barr and Harrison, the two who were wearing their seat belts, were injured but survived. From the Butler County Sheriff’s accident report: “Although the final toxicology tests are still pending, investigators have stated the initial blood tests recorded a blood alcohol level for driver Van Dyne at .056. (Ohio’s limit is .02 for any person under the age of 21.)”

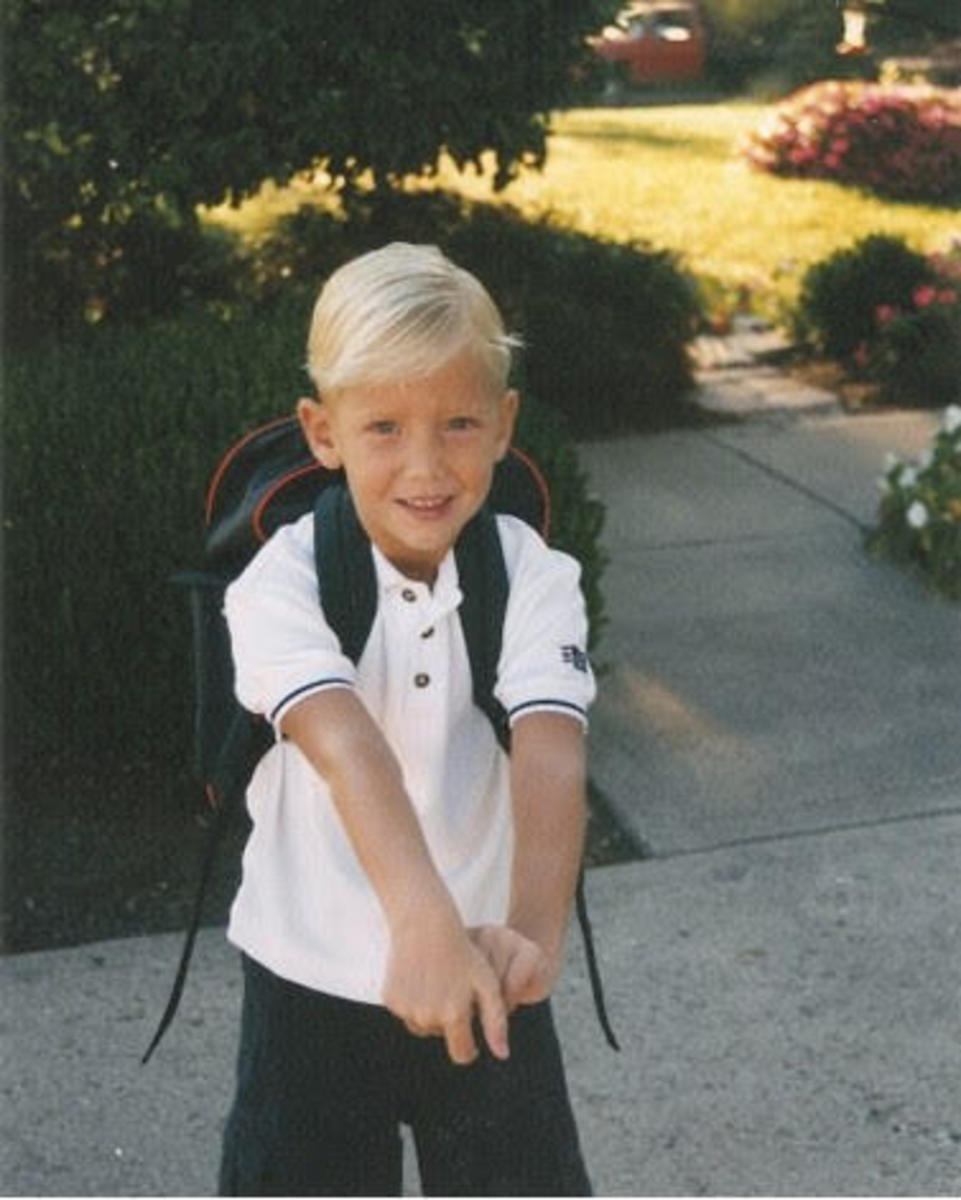

The devastating news spread quickly. A steady flow of friends and family came to Rick’s house through the night. By the following evening, a makeshift memorial had been set up at Hamilton High School, Flick and Van Dyne’s alma mater. People flocked there to express their grief over Ben’s passing—a 6' 6", 285-pound giant of a young man with a gift for making others laugh. “It wasn’t ever over the top,” Rick says. “But he was never very shy.”

The Cincinnati football program was rocked, as well. Offensive guard Austen Bujnoch told the Associated Press at the time that when the Bearcats went back to practice for the first time after the tragedy, there wasn’t a single spoken word among the players all day. “One of the hardest things we ever went through,” says Widecan, who has worked with Cincinnati football for 33 seasons.

Sitting in that conference room eight years later, Rick isn’t one to open up his emotional vault while discussing that awful night. He speaks matter-of-factly. But he occasionally squeezes his eyes shut while talking. Or looks up at the ceiling. Going there will always be hard.

A previous jarring tragedy already had deepened the bond between Rick and Ben—“We were just a pair,” Rick says—and in an instant they were torn asunder. The two closest people in Rick Flick’s life had been taken from him. How was he supposed to keep going?

In 2008, Rick and Theresa Flick moved into their dream home in suburban Hamilton with their teenage son. Theresa lived there for a week.

She had lived a difficult life with brittle diabetes, suffering through multiple organ failures and had undergone multiple transplants. There were treatment trips to the University of Minnesota hospital, the Cleveland Clinic and elsewhere. On Aug. 23, 2008, she died at age 45.

That left a widower and his grief-stricken boy to lean on each other.

They were not biological father and son—a little-known fact that became increasingly obvious as Ben grew to tower over his diminutive father. Ben was born in 1994 in South Carolina to a woman who was originally from Cincinnati; in dire financial straits, she moved home and gave up Ben for adoption. With Theresa Flick’s diabetes, natural childbirth was a risk. So she and Rick opted for adoption, and on the appointed day arrived at a location to pick up Ben.

After Theresa’s passing, Ben and Rick became road-trip sidekicks. They jumped in the car to visit Civil War sites, flew out West—and, increasingly, took off to attend football camps as Ben developed a passion for the sport. “We were always going on these adventures,” Rick says. “I had a great, great, great time.”

Ben’s goal was to become a Division I college player. He asked for the assistance of a personal trainer to improve his agility, and Rick got him one. By his sophomore year at Hamilton High, Ben started to attract college attention. After his junior season, the camp circuit took on added importance. Among the dozens of interested schools were Michigan State, Marshall and hometown Cincinnati. At Cincinnati’s camp, Ben’s performance was strong enough that then head coach Butch Jones called him and Rick into his office to say, “I’ve got to have you.” When a scholarship was extended in June 2012, Ben accepted it. The dream was within reach.

Jones left after the 2012 season for Tennessee and was replaced by Tuberville. Ben had already signed with Cincinnati and kept his commitment. He wanted to play in his hometown, with his dad nearby. They had gotten that far together.

When Ben died without ever playing a snap, four games into his redshirt season, the Bearcats refused to let it end there. Repeatedly, people within the program reached out to Rick to check in on him. When Cincinnati made the Belk Bowl in December, three months after Ben’s passing, Rick was invited to join the team in Charlotte for the game. After that season ended, the finality of what happened hit home. But the emotional emptiness that followed was filled, in part, by the desire to fulfill his son’s four-year commitment. “I had to do something,” Rick says.

“If it was me, I couldn’t take the reminder,” Murray says. “I’d never want to be around these people again. But Cincinnati is never going to go away for him. I think he needed us badly.”

The next season, 2014, Cincinnati was renovating its home, Nippert Stadium. The school moved its home games to Paul Brown Stadium, where the Bengals play, and that sparked a thought in Rick’s head. I know my way around a stadium, and they might need my help with this season in a strange place.

From 1988 to ’93, Flick had been the manager of the visiting clubhouse at Riverfront Stadium, home of the Cincinnati Reds. The sixth of seven children born into a German Catholic family in Cincy, he didn’t have the time or money for college but did have an abiding love for baseball dating back to the Big Red Machine of the ’70s. When the opportunity arose to get a job at Riverfront, Flick made the most of it.

A single guy in his mid-20s, Rick loved meeting the stars of the National League and attending to their various needs. Rick carried Jim Leyland’s cigarettes for him when the Pirates were in town, slipping him a “heater” in the dugout between innings. He drove Vin Scully to mass one Sunday. (“Hearing Vin Scully say the ‘Our Father,’ that was something.”) He became adept at making things happen on the fly, fitting into a baseball lifestyle that was fast and loose.

“Listen, I had a great time,” Rick says. “I just love that old-school, smoke-a-cigar clubhouse thing. I used to be a Runyonesque character. Now I'm just run-down.”

But the self-described “stadium rat” still knew some stuff in his putative run-down state. So, it made sense when the nuts-and-bolts guy talked to the UC equipment staff in 2014 and volunteered his services.

“I just kind of hit the ground running,” Rick says. “Not that it’s neuroscience, but stadiums are all very similar, and I just know where to get things. It’s just kind of this Morgan Freeman, Shawshank Redemption [thing where I’ve] been known to get my hands on a thing or two—all within federal and state guidelines.”

When the locker rooms had no hot water at the 2014 Military Bowl, which was played in chilly temperatures in Annapolis, Md., Flick tracked down the stadium ops guy at home and coaxed him into coming in to fire up the boiler room. When there was no air conditioning in the locker room for an early-season road game in a warm-weather locale, “someone” expropriated several fans from the home locker room before halftime. “I’m not saying it was me,” Rick says with a wink. “Things happened.”

"I thought he was just a maintenance guy when I first got here, but he is the most unique person. ... I’ve known plenty of people who show up for the party after the work has been done. Rick is there for the work, and he’s usually the first one there and the last to leave." —Luke Fickell

His company, O’Brien Supply, has a box truck that Flick has put on loan to the Bearcats to help haul equipment to road games. And he paid out of his own pocket to custom-wrap the school’s primary equipment truck with a new design.

But the son of an electrician truly excels when working with his hands. He can, in his own humble estimation, “fix anything,” and there are plenty of stories to back that up. Flick personally refurbished the team’s helmet locker. He has jerry-rigged sideline headset repairs. When the heated benches weren’t working at East Carolina last month, Flick fixed that. His backpack is a renowned reservoir of obscure supplies—from tools to keys to a spare Red Bull for any strength coach in need.

Other people run away from problems. Flick runs toward them.

“The things nobody has time to do or wants to do, that’s what Rick loves to do,” Murray says. “He’s always popping up saying, ‘What do you need? How can I help? Need a Fresca?’”

When Fickell replaced Tuberville in 2017, he could have told Flick thanks, but no thanks. Football coaches often are keenly paranoid and controlling, wanting their “own guys” working in the facility. Instead, Fickell welcomed Flick to keep doing everything he does.

In 2017, Cincinnati’s second win under Fickell was against Miami (Ohio), nearly four years to the day after Ben Flick died. The head coach grabbed the game ball and awarded it to Rick—his commitment paid in full. But it didn’t stop there, and neither did Cincinnati’s winning. Fickell presented Rick a game ball again this year, after the Bearcats opened this undefeated season with a victory against the RedHawks.

“He’s kind of the essence of what we want to be,” Fickell says. “We want to be about the guys who want to do the grunt work, be humble about what it is they’re doing. He wasn’t recruited here and I didn’t know him, but he’s exactly what we want the culture of the program to be.”

Rick Flick sold his big suburban home a few years ago. It carried too many painful memories, so he moved into a smaller space downtown. He also started to attend a support group for people who have lost their spouses.

At one meeting, he encountered an energetic ER nurse from UC Hospital. Her name: Nancy Prosser, the widow of former Xavier and Wake Forest men’s basketball coach Skip Prosser, who died of a heart attack in 2007. After a few meetings, Rick invited several people from the support group to a party at his place, Nancy included. At the party, Nancy thanked Rick for the invitation. He suggested they hang out together sometime. She proposed a bike ride on the Loveland Trail. He impressed her by making it 20 miles.

They’ve been dating about three years now.

As with Cincinnati football, Rick is always ready to jump into the breach. When Nancy had a snake crawl into her house via a windowsill flower box, she called Rick to dispose of it. (Humanely; she’s an animal lover. Rick refers to Nancy as “Snow White” for her kinship with birds, deer and horses.) When Nancy’s 86-year-old mother needed shrubs removed from her front yard in Louisville, Rick made the 200-mile round trip to spend the day helping tear them out.

“He’s always positive, always upbeat, always eager to reach out and help,” Prosser says. “He’s been through a lot and has a great attitude. He’s a breath of fresh air. We’ve been through some similar things and he’s just very easy to talk to.”

Prosser will make the trip to the Dallas-Fort Worth Metroplex this week for the biggest football game in Cincinnati’s history, against Alabama in the Cotton Bowl CFP semifinal. It’s a trip Rick couldn’t have envisioned in 2013, or really any other time before last year. Cincy got close to the playoff in ’20, and now it’s broken the Power 5 Conference stranglehold. For a kid who grew up in Cincy, where the Bearcats were an afterthought to all things Ohio State, these are heady times.

“Sometimes I can’t get my head around it,” Flick says. “When you sit and think, ‘Good Lord, we're going to be playing Alabama.’ I mean, Alabama, for God sakes. You know, I’m not an X’s and O’s guy. I can’t. I’m more of a fan. But we really think we can compete; we really, really, really do. I think they can. I think they will.”

Rick Flick’s small but important part in this game is already underway. He’s had work to do.

On Christmas Eve, Rick Flick boarded a flight for DFW alongside student operations intern AJ Wessel. They were the advance team preparing the way for the Bearcats.

Operations director Widecan entrusted Flick with that job a few years ago, sending him in before every road game to handle the voluminous logistics of a college football travel contingent. First stop is the hotel to arrange check-in, meeting rooms, a dining area, a training room and unload equipment from the truck. When the team arrives the next day, the buses are dispatched to the hotel to pick up Flick and Wessel, who then ride to the airport and direct players and coaches to their respective buses. Back at the hotel, Flick orchestrates the check-in transition.

“You have to understand that you take what the coaches want and get it done however you can,” Widecan says. “Rick and I get along well because we figure out how to get things done.”

The two have bonded over a love of the band Rush and Bearcats football. But Flick also has become a valued mentor for the young people within the program’s support staff, including Wessel. Road trips with Rick tend to be life experiences for student assistants in the equipment and training staffs, as much about the wisdom dispensed as the work put in. The days spent with his own college-aged son were so tragically brief; these trips are Rick’s opportunity to engage in some of the moments he never had with Ben.

“He’s like a second father to me, if I’m being honest,” Wessel says. “Bearcat football is his family, and he’s our family. It’s like this program is his own house, and he’s helping build it.”

More College Football Coverage: