Group of 5 vs. Power 5? That’s Not How Cincinnati Sees It

Inside the Cincinnati football facility there is an unwritten rule. There is a term that is largely forbidden, an expression not often uttered.

Power 5.

“I don’t use the phrase,” says Luke Fickell. If he must refer to what’s deemed the upper level of college football conferences, the Bearcats coach instead uses another name.

“P-whatever,” he says.

Whenever a new coach joins his staff, the rookie must be indoctrinated into this ideology. Not all of them get the message. During a recruiting meeting once, a new assistant mentioned that a particular prospect had several Power 5 scholarship offers. Oops. Fickell leaned over to another staff member, “Better get this guy up to speed.”

The Power 5 moniker, as well as its oft-labeled and peripheral counterpart, the Group of 5, brings out fiery sentiments among many across college football. Born years ago during the BCS era, the Power 6, then including the Big East, designated the six conferences with BCS bowl tie-ins. The moniker is now used to separate the richest 65 schools in the sport, residing in the five leagues that each possess two unique qualities among the 10 FBS conferences: a New Year’s Six Bowl tie-in and one of the five largest television contracts. That group includes independent Notre Dame, which is traditionally considered among the Power 5.

For many, this is a fabricated dividing line, an aristocratic maneuver to further separate the haves and the have-nots down revenue-generating delineations.

“I hate the Group of 5 moniker,” says Mike Aresco, commissioner of the American Athletic Conference and one of the most publicly outspoken critics of the labels. “The whole thing is silly.”

“I hate quantifying the groups,” bemoans Craig Thompson, the Mountain West commissioner. “It’s not as though the [Power 5] teams have ascended to some place.”

The G5 vs. P5 battle has raged for the better part of the last decade. Each time a team from the so-called inferior five leagues pulls off a victory over their purportedly superior upper half, substantial crowing is involved. The argument has reached even one of the most powerful governing bodies in the sport, the College Football Playoff’s executive board of commissioners, where the labels are at the center of a potential expanded format.

On the field, little brother has won some significant fistfights this season. Group of 5 teams won 16 of 77 games against the Power 5 during the first four weeks of the season, the window in which such interleague games are primarily played. That 20% winning mark that largely aligns with the G5’s success rate over the last two decades. But this year, a pair of victories came over eventual Power 5 champions. Western Michigan, of the MAC, beat ACC title-winner Pitt, and BYU, an independent, took down Utah, which claimed the Pac-12 championship. In the first five bowl games to feature the two entities clashing, the Group of 5 won all five: UCF beat Florida, Utah State beat Oregon State, Army beat Missouri, Houston beat Auburn and Air Force beat Louisville.

The Group of 5’s grandest event arrives Friday here at the Cotton Bowl. Fickell’s Cincinnati team has a shot to attain the biggest win over a … P-whatever in the modern history of college football. The No. 4 seed Bearcats (13–0), AAC champions and by far the best G5 team this season, meet top seed Alabama (12–1), the SEC title winner and for a decade now the king of the Power 5s.

Fickell, though, wants to clear the air. “We’re not carrying a flag for the little guys,” he says flatly.

Why not? This is a game between Cincinnati and Alabama, not between the Group of 5 and the Power 5, he says. Fickell doesn’t separate or see any striking difference between what he calls “the P-whatever and the G-whatever.”

Soon, in fact, his program will be on the move, from the G-whatever to the P-whatever. The Bearcats are expected to begin playing in the Big 12 by 2023.

“If anybody asks me in two years when we move to the Big 12, I will say there is no difference between leagues,” Fickell says. “Why would we try to separate ourselves? ‘Oh, you’re not going to say that when you’re with the bigger guys!’ No, I will say that.

“We all understand there are discrepancies in money. The majority of that goes to the coaches. Coaches are paid more. We all know the facilities are different, but really, what’s the difference? That’s the way I look at it and that’s what we preach to our kids. We don’t allow it to be an excuse for recruiting.”

The lower tier of D-I football fights a perception problem just as much as it fights a financial problem. The P5 vs. G5 debate is used against the sport’s lower tier on the recruiting trail as much as anywhere else. For instance, while athletic director at UCF, Danny White, now the AD at Tennessee, says his coaches would often tell him that some recruits wanted to sign with a Power 5 program.

“What does that even mean? It’s a term that’s become so mainstream as if it is a differentiator,” White says.

Fickell acknowledges that conference affiliation, and not the financial or facility disadvantages, is used against the Bearcats in recruiting battles against Power 5 programs. “You’ll be amazed,” he says, “it’s what people use. To be honest, it’s unfortunate that it does have a greater effect on 17-year-olds than you think. It’s something that to me hangs over your head a bit.”

In many ways, it is a domino effect. Power 5 programs regularly play bigger games than those in the G5. Bigger games lead to more television revenue, which filters to the schools, lining their coffers with more cash that is then used on improving facilities, hiring better coaches and, in the end, attracting better recruits.

The financial gap between the two groups is unmistakable. Only one G5 team has a budget that is bigger than any Power 5 program: UConn at $78.7 million. That ranks above the bottom two P5 budgets: Washington State and Oregon State. More than half of the Power 5 schools have a budget of at least $100 million.

The money issue is rooted in TV contracts. The AAC has the richest television deal among Group of 5 conferences, distributing slightly less than $7 million to each school, nearly $20 million less than the lowest P5 conference’s TV distribution rate.

The latest conference realignment wave, set off by Texas and Oklahoma’s move to the SEC, only widens the gap. The Group of 5’s top three public universities in athletic budget—Houston, UCF and Cincinnati—are leaving behind their G5 partners to play with the big boys.

“The only gap between the Power 5 and Group of 5 is money,” says Auburn coach Bryan Harsin, who led G5 Boise State for years before landing in the SEC. “The money piece … you use for facilities. It does affect players and what you’re able to do, but we do all those things. It might not be as easy to do it financially. Got to go out and raise it.”

Cincinnati, a 13.5-point underdog to the Crimson Tide, has a shot to make history in more than one way. Since the AP poll began in 1936, only two programs from current Group of 5 leagues have won national titles: BYU in ’84 and Army in consecutive years in ’44 and ‘45.

Since 1998, eight Group of 5 programs have finished the season undefeated. There was Tulane in ’98 and Marshall in ’99. Utah and Boise State each completed perfect seasons twice during the BCS era. The Utes, now in the Pac-12 and then in the Mountain West, went undefeated in 2004 and ’08. Boise went unblemished in both ’06 and ’09 under coach Chris Petersen. In ’10, TCU finished third in the BCS rankings, missing out on a shot at the national championship by one spot before beating Wisconsin in the Rose Bowl. And, of course, in 2017, UCF placed 12th in the final Playoff rankings, but famously claimed a national title after going 13–0 and ending up the only unbeaten FBS team.

Petersen says he never worried about the Broncos’ bowl or championship situation. It was the “wrong mentality” to have in front of the team.

“It’s just a waste if you think about it. And those who think about it are sure going to get beat,” he says. “I think Cincinnati is good enough. I get it; they’re not playing the same caliber teams from top to bottom, but I look at their talent and they’ve got some dudes.”

In other sports, programs outside the Power 5 have either won it all or regularly had the opportunity to. Since 2003, four non-Power 5 programs have won College World Series titles. And in men’s and women’s basketball, a postseason field of 68 starkly contrasts with the exclusivity of the football Playoff, leading to programs like Gonzaga, Houston and Loyola Chicago making recent men’s Final Fours.

Football, though, is different. Quality depth is a critical element that some smaller programs lack, a byproduct of a recruiting disadvantage. Group of 5 programs have signed roughly 240 classes over the four years before the pandemic hit (2016–19). None of those have finished in the top 30 recruiting classes.

The talent gap between Alabama and Cincinnati is wide. Just look to the last four recruiting cycles. The Tide have signed a combined 86 prospects rated four- and five- stars. Cincinnati has signed five.

“We’ve heard a lot about this David vs. Goliath talk, but the fact of the matter is, everybody puts their pants on the same way,” says Bearcats offensive lineman Dylan O’Quinn.

Some programs, though, have an inherent advantage, especially with pollsters. It took Cincinnati multiple years to build up respect among voters, putting itself in position to become the first Group of 5 team to advance to the Playoff. The Bearcats won 11 games in both 2018 and ’19 before completing a 9–0 regular season last year, capping it with a 24–21 loss to Georgia in the Peach Bowl. They led 21–10 entering the fourth quarter before the Bulldogs rallied for the win.

They started this season No. 8 in the rankings, 13 spots higher than they began 2020. Is it fair that Cincinnati needed multiple years to make its case?

“Call it fair or not,” says Fickell, “it is reality.”

The Bearcats also needed help from the Power 5. The 2021 Pac-12, Big 12 and ACC champions each have multiple losses. Oklahoma State had a shot to finish 12–1 if it would have beaten Baylor in the Big 12 title game. The Cowboys came up less than a yard short when a fourth-down run failed at the goal line in the final seconds.

Fickell, though, wasn’t as worried about Oklahoma State jumping the Bearcats. He was concerned about a two-loss Alabama moving ahead of them. If Georgia had stormed back to beat the Crimson Tide in the SEC championship game, what happens then?

“They are the reigning champs. Who are you going to take—Alabama or OK State?” asks Fickell. “I can tell you that 98% of people, I know where they’re going to go.”

When factoring in strength of schedule, it is conceivable that a two-loss Tide would have leaped the Bearcats. Three of the four CFP participants have a strength of schedule in the top 30. Cincinnati is the outlier with a schedule that ranks 79th, according to Jeff Sagarin’s ratings.

“I had my reservations about Cincinnati, but once they beat Houston [in the AAC championship game], I felt like they deserved to go in,” says Tommy Bowden, the former Clemson and Tulane coach who went undefeated with the Green Wave in ’98.

That year, Bowden didn’t argue that his team should have qualified for the BCS national title game. He knew its strength of schedule was not good enough.

“I had coached 11 years in the SEC. I knew how difficult it was to go back-to-back-to-back SEC games—Gainesville, Tuscaloosa, Knoxville. At Tulane, I didn’t have to do that,” Bowden says. “I remember people calling and I said, ‘I’m not complaining. We don’t deserve it.’”

Soon, a Group of 5 team might have automatic access to compete for all the marbles. The CFP management committee, made up of the 10 FBS commissioners and Notre Dame AD Jack Swarbrick, has been exploring expanding the Playoff for nearly three years. However, the group has fallen into a rut. Expansion talks are somewhat stalled, mainly over two issues: the number of teams in an expanded playoff (eight or 12) and which leagues get an automatic bid. A 12-team proposal that grants automatic bids to the six highest-ranked conference champions would guarantee the best Group of 5 team a playoff spot.

“Hopefully this is a short term deal, that we stay at four for not too many more years,” says Thompson, who is one of eight of the 11 management committee members publicly in support of the 12-team proposal. “The G5 will have an automatic [bid].”

One Group of 5 administrator has a suggestion for a very different model. Sean Frazier, athletic director at Northern Illinois, has publicly stumped for a separate Group of 5 playoff. The five G5 champions would play in a tournament with the champion advancing to the CFP.

Cincinnati advancing temporarily derails the narrative that a G5 program can’t make a four-team playoff, he says. But it took what he calls a “perfect golf swing.” Without the Bearcats’ win at No. 5 Notre Dame, “they don’t get in,” Frazier says. “It was smart scheduling, but who can forecast that? A win over a top-five team.”

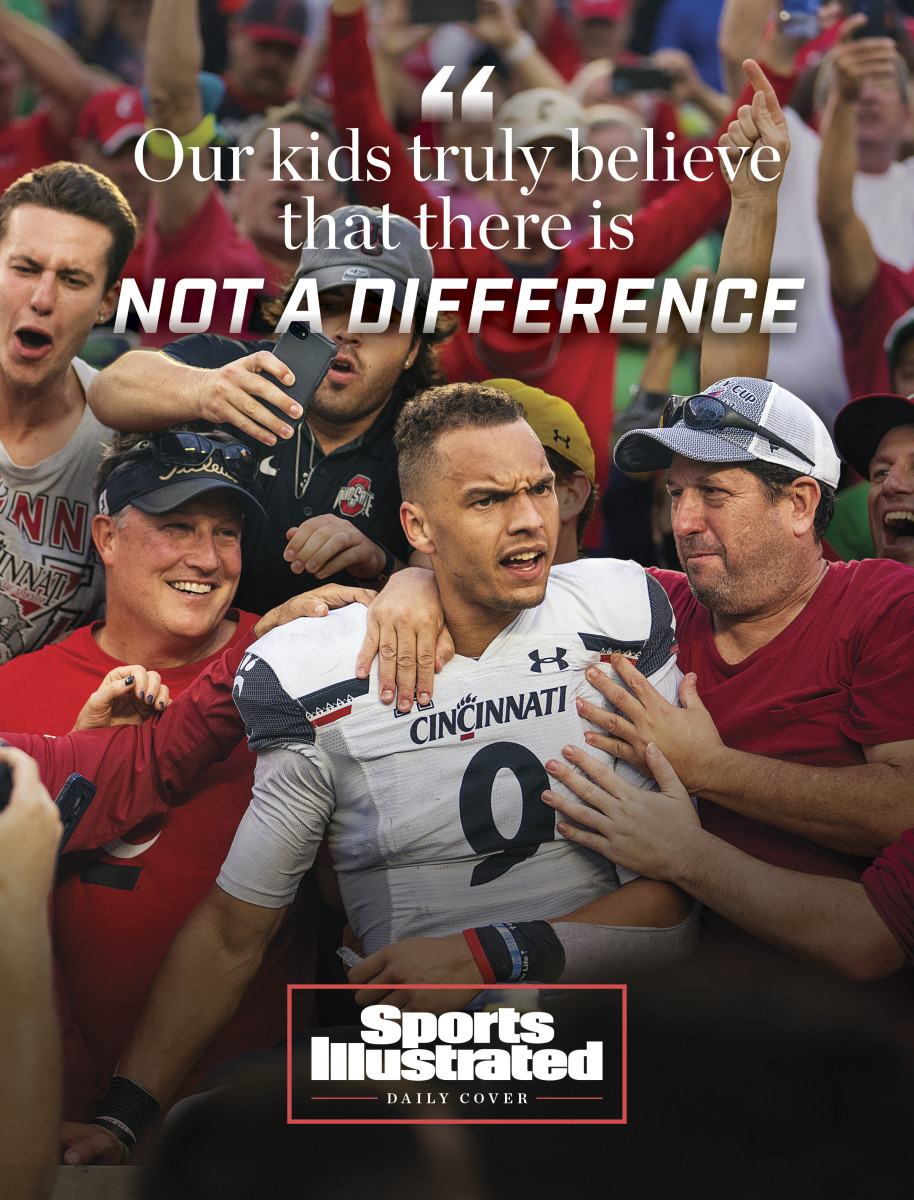

Meanwhile, back in Cincinnati, everyone knows the certain phrase that isn’t to be used in the football facility. In fact, Fickell says his team is taking that message to the field. During the Peach Bowl last year against Georgia, the coach saw that in his players.

“I think I learned that our kids truly believe that there is not a difference,” he says. “I think it’s easier for them to believe what we’ve always talked about than even our coaches. There wasn’t this sense of ‘uh-oh,’ even in the midst of the game with a [Georgia] receiver running by us and a 6' 7" defensive lineman across from us.

“We are fortunate we do have the scrappy, hard-nosed kid who doesn’t recognize the differences.”

Wait, so there are differences? Eh, who really can say?

One thing Fickell isn’t saying: Power 5.

More College Football Coverage:

• Rick Flick Lost a Son. At Cincy, He Found New Purpose

• Deion Calls Games vs. Power 5 the ‘Ultimate Sellout’

• The Players Who Will Swing Alabama vs. Cincinnati