Nick Saban’s Seamless Pivot to Modern Coaching Style Paid Dividends in Bama’s Title Hunt

As things were proceeding poorly against Tennessee on the night of Oct. 25, Alabama coach Nick Saban knelt in front of Bryce Young for a brief sideline talk. Their foreheads almost touched, as Saban calmly and intimately gave his 20-year-old quarterback some counseling, Things eventually got better, with a 28-point fourth quarter keying a 52–24 victory.

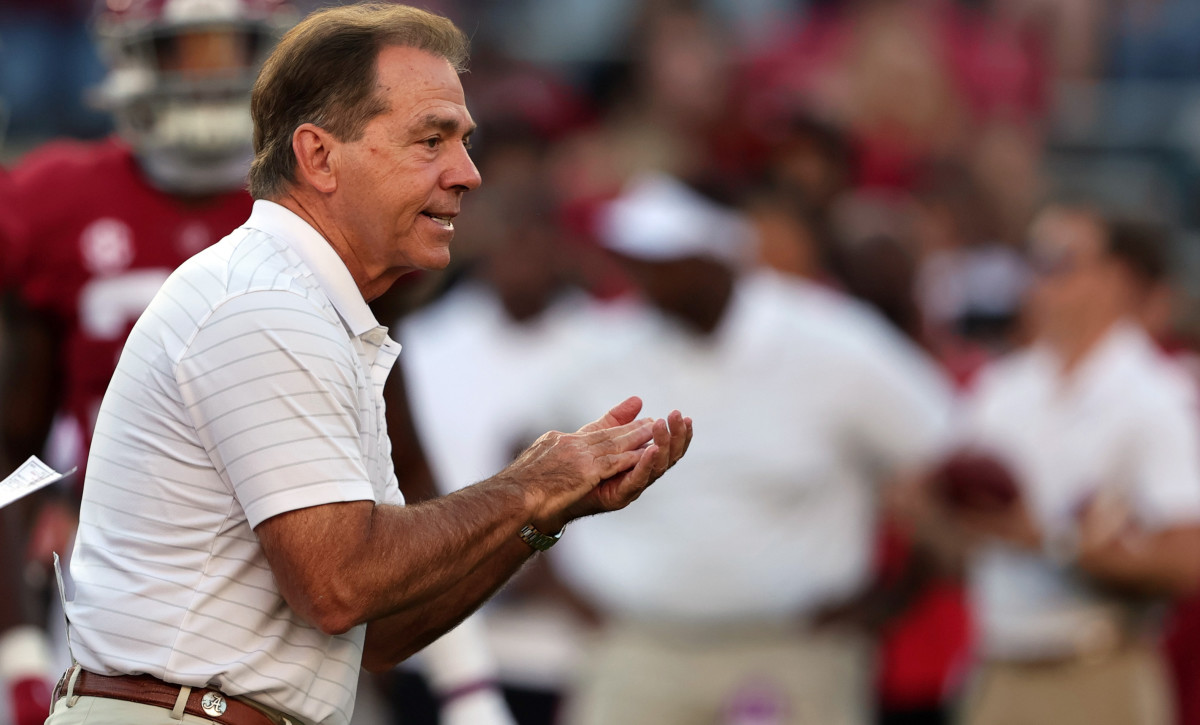

This was a side of Saban the world rarely sees. Normally a cauldron of in-game intensity, occasionally raging at assistant coaches or players or officials, this was a different style of coaching. Lowering himself to a player’s level on the bench and quietly speaking eye-to-eye demonstrated an oft-overlooked Saban gift: At age 70, he’s attuned to what people half a century younger need from him.

“I think one of the many separators for coach Saban is his ability to manage a wide variety of kids from different backgrounds, and kids who are wired differently,” says Alabama athletic director Greg Byrne, who is as well-positioned to observe Saban as anyone. “When I was growing up, if your coach told you to do something, you just did it. You didn’t think about it. The ‘why’ is now a big part of coaching young people. Because of how smart coach Saban is, he’s able to express the ‘why’ as well as anybody out there.”

Given his accomplishments—seven national titles, six of them at Alabama between 2009 and 2020, and perhaps another on the way—we would forgive Saban for believing he already has all the answers, to everything. Do it his way, or get out. But he’s always willing to adapt his teaching style to what his pupils will best respond to—and in today’s college football, that means softening some of the famously hard edges.

“He’s so different now,” ESPN analyst and Alabama starting quarterback in 2009 Greg McElroy declared on Young’s podcast in October. “Coach has changed so much.”

The fact that his quarterback has a money-making podcast is the first evidence of Saban’s evolution. Whatever players can accrue through Name, Image and Likeness rules, Saban is fine with—as long as it doesn’t deter focus and preparation. The authoritarian coaching figure is a thing of the past, and few pivoted toward the new style more adroitly than Saban.

Particularly with this team.

For a guy who recently declared, “I don’t have any patience,” Saban has exhibited a lot of that trait this season. He understood that the 2021 Alabama team was going to be a work in progress, after last year’s overpowering squad stormed through the season undefeated and sent 10 players into the NFL draft, six in the first round. Leadership had to be developed, and it was going to take some time.

There was a narrow escape at Florida, an upset loss at Texas A&M, struggles against Tennessee and Arkansas and LSU and Auburn. At midseason, a national championship seemed a long ways away. After the A&M loss, Saban seemed closer to a mayonnaise bath (God help the bowl official who would have had to suggest that to one of America’s most mirthless men).

Yet here he is, prepping to play for yet another natty Monday night against Georgia, with a team that is nowhere near as good as last year’s. As one former Southeastern Conference coach told Sports Illustrated this week, the Bulldogs are better 1–44 on the depth chart, and this year’s draft will underscore that. But Alabama has the Heisman Trophy winner at quarterback, perhaps the best defensive player in college football in linebacker Will Anderson—and the greatest coach of all time.

Much the way the other pre-eminent 70-something coach in college athletics, Mike Krzyzewski, remodeled his coaching, so too has Saban. What worked in 2003 might not work in 2021. Especially with a younger team that hasn’t accumulated as much Saban scar tissue.

When asked how many of the famous Saban “ass chewings” he’s seen during games, Byrne said, “not a lot.” But defensive coordinator Pete Golding chuckled earlier this week when asked whether the amount of ass that has been chewed by Saban has decreased in 2021.

“That’s absolutely not accurate,” Golding said. “Whatever you do here, Coach is going to make sure you do it to the best of your ability. You do it the way he sees fit, which I enjoy. The good thing about him is it’s black and white and you’re going to know.”

Saban may never roar at assistants as much as he did when Lane Kiffin was the impish offensive coordinator. But the Saban seen on TV during games and experienced behind the scenes in practice has adapted. Perhaps even softened, at least in terms of his interactions with the current players.

"I don’t want to call it nurturing, but I felt like we needed to do that with this team,” he said before Alabama’s trouncing of Cincinnati in the Cotton Bowl. “Just getting on these guys all the time was not going to help their confidence. It was not going to help the young players develop.”

That seems to start with Young. He was a huge talent and highly sought after coming out of high school in California, and Saban got him the same way he gets most of his players—by promising them nothing in advance, but giving them a chance to earn one of the most coveted things in college football: playing time at Alabama.

Young came into this season having thrown 22 college passes, all of them in mop-up duty last year while backing up Mac Jones. He had the talent, but didn’t have the reps. To borrow Saban’s favorite word, this was going to be a process. The rudimentary stuff—getting plays off on time, calling protections at the line of scrimmage, learning when to throw the ball away—would all take time.

The end result is a 13–1 record, a spot in the championship game and a Heisman Trophy for Young. But that doesn’t mean it has all unfolded seamlessly.

Struggles were interspersed with brilliance throughout the season. Nothing encapsulated that better than Young’s performance at Auburn, where he was largely awful for 58 minutes before leading a 98-yard, game-tying drive to push the game into overtime. The Crimson Tide won in OT, then morphed into an offensive monster the next week against Georgia in the SEC championship game.

Saban was almost effusive after the Auburn game, perhaps sensing how far he’d taken this team. “This is something that you should always remember,” he told his players. “It’s the feeling of being on a team. The feeling of togetherness of everyone making a commitment to support each other and be positive and trust and believe in each other enough to go out there and make these kinds of plays that makes it a special win.”

If you had administered truth serum at that point, Saban might have admitted that beating Georgia the next week and advancing to the College Football Playoff seemed unlikely. But here they are, driven hard but also encouraged and supported along the way.

We’ve seen Nick Saban win national championships with defense. Then we saw him win them with offense. But we always saw him win championships with a simmering intensity. Now we may see a kinder, gentler Saban win one, in what would could be his best coaching job yet.

More College Football Coverage:

• Is the SEC’s Playoff Dominance Bad for College Football?

• Three Years After Talks Started, Can CFP Expansion Get Over Its Hurdles?

• Film Room: What Does Georgia Have to Do Differently This Time vs. Alabama?

• Why Have Southern Teams Dominated the CFP? Follow the Money, and History