Forty Years Ago an HBCU Played in the First Women’s Final Four. Today the Program Is Gone.

Four days before Selection Sunday, one of college basketball’s most hallowed halls lies almost entirely dormant. Only a single person, Tammy A. Bagby, the director of athletics at Cheyney University of Pennsylvania, is inside working in her office, a mere chest pass from the entrance to the arena floor. On this sleepy Wednesday in mid-March, the gym’s retractable bleachers are pushed in. A few Wilson basketballs are scattered across the court, while a chalkboard and equipment for shooting drills sit nestled in one corner. Three banners hang on the opposite end, remnants of a time when Alfred Cope Hall was home to dominant men’s and women’s basketball teams.

Among the signs is one honoring the school’s 1978 men’s NCAA Division II championship, though it’s slumping ever so slightly thanks to a missing zip-tie at the top. Another banner, placed just to its right, lists the successes of the women’s program. Chief among them is finishing as the runner-up at the ’82 women’s NCAA Division I tournament, the first time the competition had taken place.

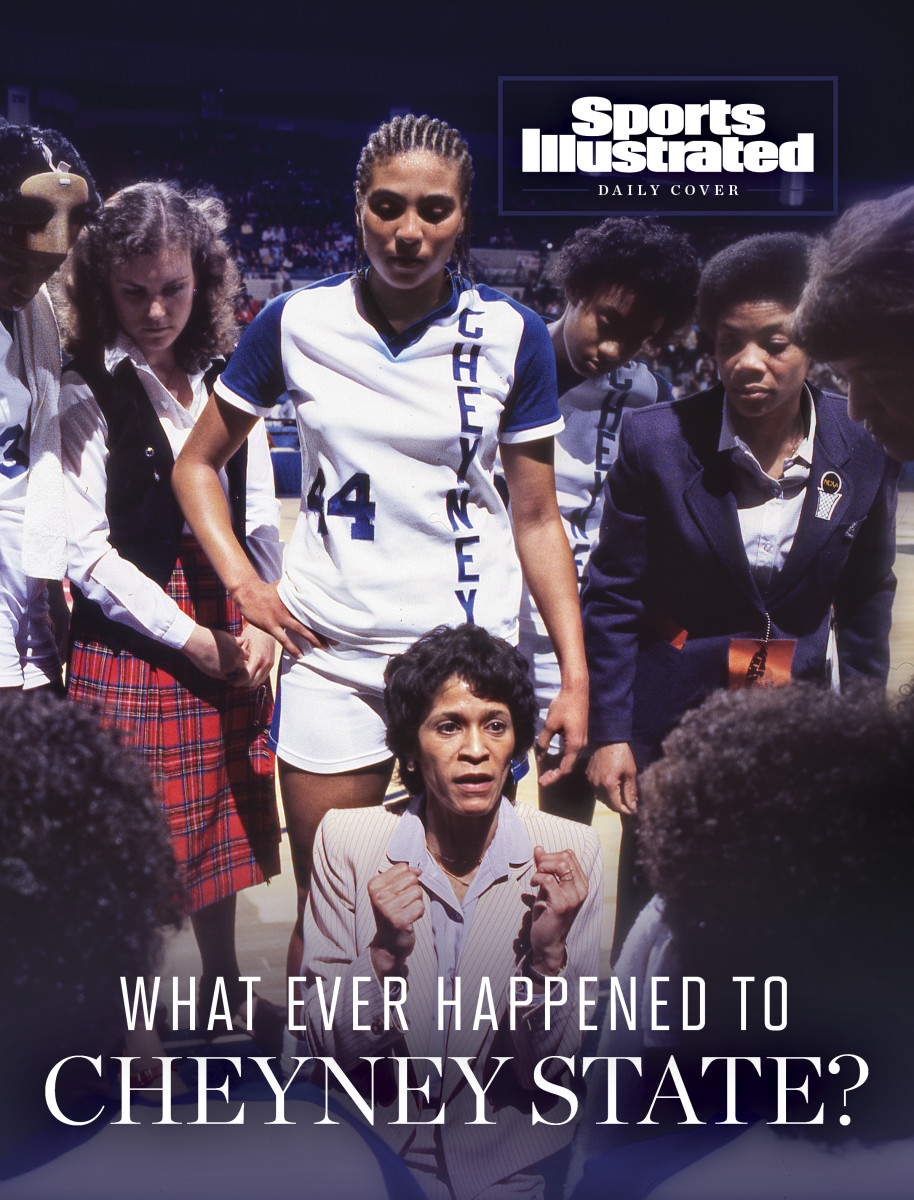

Cope Hall is likely the most historic building in the sport that you’ve never heard of. Built in 1961, there are plenty of modern-day high school facilities with better physical amenities. Still, Cheyney, the oldest HBCU in the United States, and its Cope Hall were once home to two basketball trailblazers: John Chaney and C. Vivian Stringer. Both were on campus together at what was then known as Cheyney State College. Only three universities—UConn, North Carolina and Cheyney—have had future Naismith Hall of Fame men’s and women’s basketball head coaches employed at the same time. And the energy that used to course through the arena’s veins, “You can compare it to Cameron Indoor Stadium at Duke,” says Debra Walker, a forward on the ’82 team. “It wasn’t a matter of winning in Cope Hall. It was how much are we gonna win by.”

But this winter, 40 years after Walker and her teammates reached the sport’s most important game, there were no cheers for the Lady Wolves. Racked by financial uncertainty and the COVID-19 pandemic, the university did not sponsor a women’s basketball team for the second consecutive season. Bagby says she is in the process of hiring a new coach and restarting the program for the 2022–23 campaign. But much has changed since its glory days.

As Bagby works on the reboot, there are more ongoing efforts than ever before to pay homage to the historic 1982 run and all that it represented. Among them: Last weekend, for the first time, a luncheon was hosted on campus in their honor. “I felt what those women did cannot go unrecognized. It shouldn’t go unrecognized,” says Kyle Adams, a Cheyney alumnus and former Lady Wolves coach who helped plan the event. In recent years, there has also been a movement, led by Adams, to see the group commemorated in the Women’s Basketball Hall of Fame. And next year, per Adams, they will appear on the Naismith Hall of Fame ballot.

Inside Cope Hall, there are trophy cases scattered with reminders from that era. Plus, those who lived it are well aware of their achievement’s magnitude—Cheyney is still the only HBCU to reach a D-I Final Four, let alone a title game. “I just take a bow to this great team,” Stringer says. Still, four decades later, their stories remain largely untold.

Says Adams: “Especially in a day and time where there are so many pushes to celebrate women and celebrate women of color, why not these?”

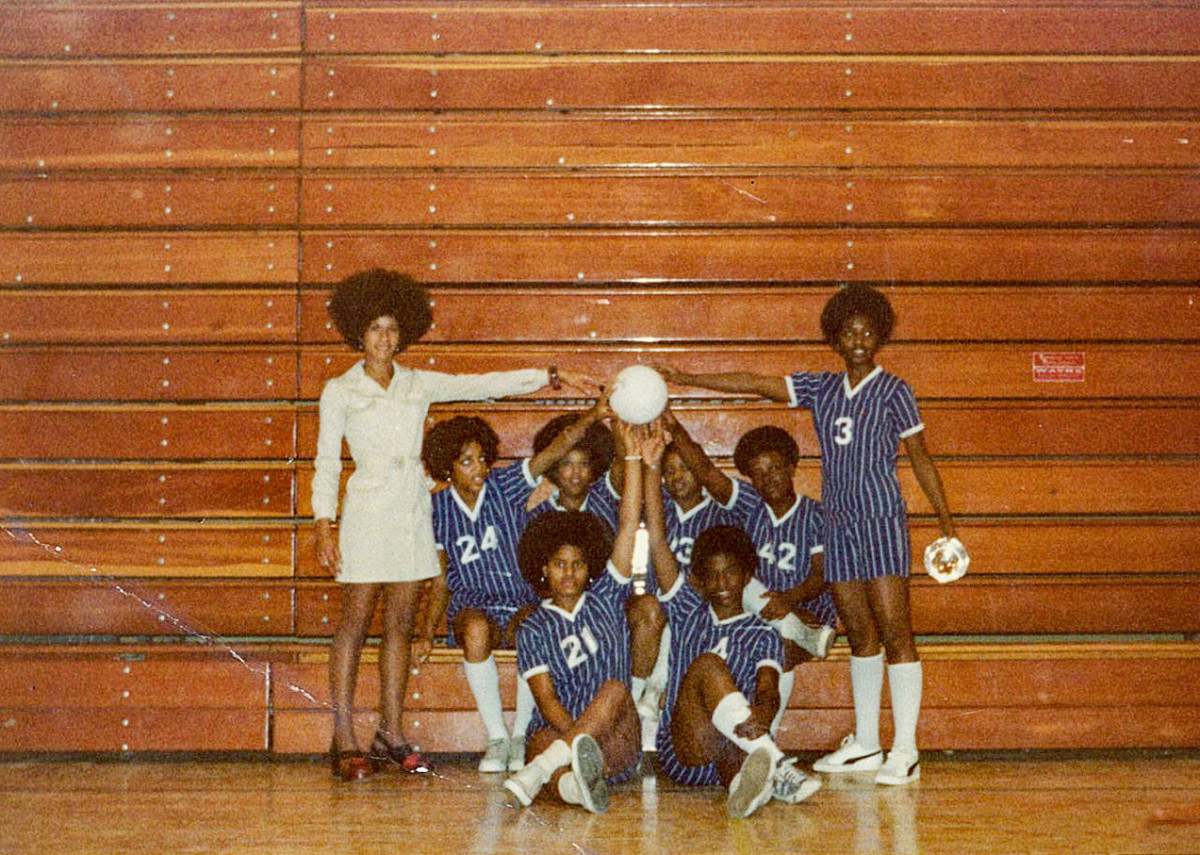

Cheyney hired Stringer in 1971 not as its basketball coach, but instead as an assistant professor. In that capacity, she taught health, physical education and organization and administration, the latter of which, she says, was a course designed to provide students with the skills needed to become athletic administrators. Each of her 251 wins with the Lady Wolves came only after she volunteered for the women’s basketball position. (She also volunteered as the school’s volleyball coach.) “Not a dime,” Stringer says of compensation for her coaching services. “I never got paid. I was just grateful to have that opportunity.”

All Stringer ever wanted at Cheyney was a chance—a chance to coach, a chance to shape young women and a chance to compete against top programs in the country. While the Lady Wolves were part of the D-II Pennsylvania State Athletic Conference, which pitted them against smaller schools like East Stroudsburg State or Millersville State, the future Hall of Famer also sought out larger D-I institutions to play, such as Rutgers, Penn State and Maryland, despite the significant financial gap between them.

The differences manifested themselves in many ways. Lady Wolves players, for instance, laundered their uniforms themselves. And for home games, they suited up in their nearby dorm instead of inside Stringer’s classroom in Cope Hall, which was the team’s de facto locker room. Often, they bused back to campus after road games to avoid hotel costs. Stringer, though, never allowed such circumstances to detract from the program, which didn’t give out athletic scholarships. “We were poor, but we never held that against us. We never felt sorry for us,” she says. “Because we didn’t have anything, we feared no one and I think that was the greatest motivation in the world.” Plus, what they might have lacked in monetary resources was also made up for in the form of basketball wealth: The men’s and women’s programs often practiced together, with the two future Hall of Famers—Stringer and Chaney—working with both teams.

The 1981–82 campaign was unlike any other Stringer experienced in her decade-plus at Cheyney. Earlier that season, her toddler, Nina, was diagnosed with spinal meningitis. As a result, Stringer spent countless nights at the children’s hospital in nearby Philadelphia at her daughter’s bedside. She missed multiple contests that season, with assistants Carlotta Schaffer and Ann Hill picking up the slack. Adams, the alumnus and former coach, believes the trio was the first coaching staff made up entirely of Black women to compete in the women’s national championship game.

By late February, the Lady Wolves had climbed to No. 2 in the country, boosted by the frenetic pace they played at on both ends. No longer a surprise, they had recovered from mid-December losses to Rutgers and Old Dominion, with forward Valerie Walker amid a second consecutive All-American campaign. “We have to do this for Ms. Stringer,” Walker remembers thinking as the season neared its conclusion. “We were all in another zone.”

That March, Cheyney pushed to be in the first-ever women’s NCAA tournament instead of what turned out to be the final AIAW tournament, as the nation’s official governing body of women’s college athletics shifted. The team cruised past Auburn in its NCAA opener, then defeated NC State in Raleigh by 13 points to win its second-round matchup days later. The Lady Wolves’ margin of victory grew to 22 in the Elite Eight as they knocked off Kansas State and advanced to the Final Four. “It was like the dream was coming true,” says Debra Walker (no relation to Valerie). Still, between tournament games, Stringer flew back to Philadelphia to be with her daughter.

Playing in the NCAA Final Four, Cheyney beat Maryland, 76–66, stretching its win streak to 23 games. “Nobody had ever heard of an HBCU doing what we did,” Debra Walker says. But there was still one game left to win.

When Yolanda Laney awoke on the day of the national championship, the star Cheyney forward wasn’t sure whether she could even move, let alone play basketball. Debra Walker, Laney’s hotel roommate, asked her teammate whether she was planning on heading down to breakfast. But Laney informed Walker she wasn’t going—she was suffering from menstrual cramps and struggling to get out of bed.

Laney did eventually make it out of her hotel room and arrived later that day at Norfolk Scope Arena, where an announced crowd of more than 9,500 people was in attendance to watch Cheyney face off against No. 1 Louisiana Tech. But Laney, who averaged 13.3 points and 6.1 rebounds per game, didn’t feel up to going out for warmups. Instead, the stadium’s public address announcer was asked to page Laney’s mother, Betty, to the Lady Wolves’ locker room.

“I’m not even gonna be able to play in the game,” Laney told her mother upon her arrival. Betty’s solution: some hot water mixed with black pepper to soothe the pain.

The concoction worked well enough that Laney took the floor for starting lineup introductions. Laney, however, says her jump shots were short all game because of how she felt and that she pushed the ball with less pace than she otherwise would have. “She fought through it like a trouper without anybody [in the public] knowing she was sick that day,” Walker says.

Despite Laney’s pain, Cheyney jumped out to an early 12–6 lead. It maintained a 20–12 cushion just past the halfway point of the first half when foul trouble by both Walkers allowed the Lady Techsters a window to come back.

With the two key Lady Wolves players on the bench, Louisiana Tech went on a late first-half run, eventually heading into the locker room up 40–26. “What would I do differently? A few things,” says Karen Draughn, one of Cheyney’s guards.

Valerie Walker, the Lady Wolves’ leading scorer, recorded 14 of her 20 points in the second half. But Louisiana Tech proved too difficult to overcome behind star forward Pam Kelly. When the final buzzer sounded, the arena scoreboard read 76–62. Cheyney had lost for the first time in its last 24 tries. “I remember we were all hurt,” Valerie Walker says. “I cried. I cried like a baby.”

As players from the small Pennsylvania HBCU sat stunned in their locker room, Stringer told the group how proud she was of their journey. “Keep your heads up. We were here. Nobody else can say that,” she said.

Upon Cheyney’s return to school grounds at around 1 a.m. that night, they received a visual reminder of their coach’s sentiment: Despite the loss, hordes of students surrounded the team bus as it pulled in, with a deejay blasting music to welcome them back. “If there were 2,000 students on campus that weekend then 1,999 were lined up waiting to greet us,” Debra Walker says. “That just showed how historic that moment was.”

And yet, many players say—whether it was due to a lack of media coverage, being from an HBCU or not feeling the urge to overly publicize their successes—their achievements have gone largely unrecognized. “We’ve been so humble and quiet about it,” Debra Walker admits. “So people can say they didn’t know, and that’s fine. But once you start telling your story, then they know.”

Adams watched the title game at his grandmother’s house in West Philadelphia. She was a Cheyney alumna and had Lady Wolves paraphernalia scattered around her home. Friends of hers from college joined them that night, as did Adams’s grandfather and mother. At 9 years old, Adams recalls not realizing it was the first women’s NCAA championship game. But he says, “I knew Nana’s school was playing on television. And I knew that those women looked like me.”

Like his grandmother had done decades earlier, in 1992 he enrolled at Cheyney, where he was struck by his ability to, in his words, “connect with my heritage, with my culture.” Adams would maintain his affinity for the university following graduation.

In 1999, he worked as an assistant coach for the school’s men’s basketball team. Then, in 2011, having coached women's basketball at many other HBCUs in the preceding years, he returned to Cheyney as an assistant for the Lady Wolves. In that capacity, he more fully dived into the program’s history and made it a priority to link his current players with the legacy planted by the team he was entranced by decades earlier. Among Adams’s first tasks when he was promoted to head coach in ’13 was reaching out to Louisiana Tech, Tennessee and the NCAA to gather anything—photos, programs, documents—related to the 1982 team.

By then, the school had not had a winning season since 1990. Before the ’83–84 campaign, Stringer moved on to coach Iowa, accepting the position, she says, despite being “afraid” to take the job “because I couldn’t imagine anybody paying me to just coach.” While Cheyney made the Final Four in the first year without her, the program drifted off the national radar soon afterward. Lacking the cachet of its Hall of Fame coach, the level of its recruits started dipping and the national powerhouses that were once on the Lady Wolves’ schedule stopped playing the HBCU.

Nevertheless, Adams still felt pressure not only to succeed on the court but also from being “this great gatekeeper of this historic basketball program,” he says.

It’s a program that currently does not exist.

This winter, for the second consecutive year, Cheyney did not roster a women’s basketball team. Back in March 2018, the university announced plans to withdraw from the PSAC, drop its NCAA D-II status and suspend most of its athletic programs. University president Aaron Walton called the moves “extremely difficult but necessary decisions” and said they would “remain in effect until we achieve our financial objectives.” The school’s accreditation had also come into question, and a $40 million debt to the Pennsylvania State System of Higher Education threatened the university’s future more broadly. Women’s and men’s basketball and volleyball survived the initial cut, but all three were eventually halted for the ’20–21 season amid the COVID-19 pandemic.

Bagby, the school’s current athletic director, was first hired in 2016 to coach women’s basketball. She succeeded Adams, who did not have his contract renewed after the ’15–16 campaign following changes to the university’s administration. She assumed the school’s AD position in July ’21. Under her leadership, and with Walton’s approval, Cheyney resumed the men’s basketball and volleyball teams this fall.

As a former point guard herself, Bagby also recognizes the importance of women’s basketball, especially at an HBCU such as Cheyney. She says she’s looking to hire a coach to reboot the program next year and find a conference for the school to compete in. “Every day I walk in and feel grateful, humbled, honored to try and rebuild athletics,” Bagby says.

Says Stringer of seeing the program succeed again one day: “I would be so proud because I have nothing of the fondest of memories of what we did.”

Adams is also trying to see those stories properly honored. In November 2019, during a road trip with Arkansas–Pine Bluff, he visited the Women’s Basketball Hall of Fame in Knoxville, Tenn. While there, he went looking for anything Cheyney-related but was disappointed when he saw pictures of only the 1981 and ’82 All-American teams, which featured Valerie Walker, and the ’84 All-American team, which showed Laney sitting next to USC star Cheryl Miller.

He chatted up a museum employee and learned that past teams could be nominated as Trailblazers of the Game. He filled out an application that winter and followed up multiple times. He's applied in 2019, ’20, ’21 and ’22.

Thinking that the 40th anniversary would make for a fitting time for the Hall to induct the group, Adams organized a virtual watch party in January on the night the honor was being awarded. Title IX, which was passed 50 years ago this spring, was the recipient instead. “My intention is I’m gonna stay on them,” he says. Another alumnus passionate about the team’s history, LeRoy McCarthy, has also submitted a separate application to that Hall and has helped the team be put on the Naismith Basketball Hall of Fame ballot in 2023, according to Adams and Debra Walker.

While Adams waits for the team to receive its long-overdue recognition, he’s taken on other efforts. Among the most significant occurred last Saturday, when, for the first time, a luncheon was hosted in Cope Hall to honor the 1982 team. Adams, McCarthy, Walker and one other alum planned the gathering, which brought together more than 200 people, including Stringer and many players. Then on Tuesday, members of the program were honored at Wells Fargo Center ahead of the 76ers-Bucks game. And a few players are also continuing to Minneapolis this weekend for the Final Four, where they will surely be asked about their triumph.

Stringer recalls that as the HBCU emerged as a dominant force in the sport, she received letters from fans around the country saying how proud they were that a school such as Cheyney could make an NCAA title game. Considering how much has changed at the university and in college athletics more broadly, it’s a run the Hall of Fame coach says almost certainly won’t be replicated. And especially not in Cope Hall.

Cheyney has announced it received a capital appropriation of $48 million to replace the arena with a larger multisports facility. There is little public information available about the renovation—multiple attempts to speak with Walton about it were unsuccessful—but the school’s website says the “capital project, already underway, will anchor the campus and bring community members onto this sprawling campus for regular use.” It’s just another reason why the recent anniversary gathering was so significant.

For now, though, in the hallway of an arena that once featured thunderous crowds, are individual portraits of the women who led a team to a point no HBCU has returned to. A Naismith Hall of Fame T-shirt signed by Stringer is in a trophy case; a copy of Stringer’s book, Standing Tall: A Memoir of Tragedy and Triumph, is placed on a side table in Bagby’s office.

“Time has a way of telling your story,” Debra Walker says. “I think it’s just the right time.”

More Daily Cover Stories:

• Why Saint Peter’s Was the Most Improbable Cinderella

• March Madness Faced a Gender Reckoning. But What’s Changed?

• Ten Years After No. 15 Seed Lehigh Stunned Duke