From Controversies to Comebacks, Kansas Completes the Perfectly Imperfect Title Run

Throughout the past 14 years of turbulence and allegations, victories and successes, Kansas coach Bill Self carried his father’s lessons with him. From the last all-of-college-basketball title he won in 2008 through every season before this one, he pulled his beloved Bill Sr. alongside, past a defeat in the last championship game held in New Orleans (’12) to the first NCAA tournament erased by a pandemic (’20).

Bill Sr., who died in January at 82 due to undisclosed reasons, taught his son that the soul of any coach is formed from two important tenets: relationships, all the nurturing and teaching that crafted individual players into a greater whole; and constitution, how leaders carried themselves in times of crisis. Senior blew up on the boy for seemingly benign mistakes, like not mowing the lawn exactly straight or giving a less-than-full effort in a practice drill. But whenever something major happened, Senior pivoted, comforting his son, helping Self assess whatever had arisen, because fixing all the minor issues helped build a foundation that could withstand any massive ones.

Friends of Bill Self joke now about the broad shoulders, oil-town ethos and upbringing in Okmulgee, Okla., his being attached to a no-nonsense basketball coach who passed along far more than a name. Self, now 59, also carried them with him back to another Final Four in New Orleans. He wanted to win for friends, for family, for his father’s memory, for past star players who didn’t lift the trophy, for the coaches who departed and for the program he long ago took over.

He also towed a burden of his own making into town, beyond the championship drought and personal grief. It stemmed from an NCAA investigation that still hangs over Kansas like an ominous cloud. The storm started gathering nearly three years ago, when the program received a notice of allegations that included five Level I violations and the heavy charge of “lack of institutional control.” (Self and Kansas have refuted the allegations, their counterargument grounded in what they called “a lack of supporting evidence.”)

Barry Hinson, who worked with Self and Kansas’s men’s basketball program from 2008 to ’12, came to view the coach as an onion, with new layers peeled away each year to reveal a more, ahem, true Self. The coach didn’t blame the transfer portal, the rugged Big 12 conference, the investigators who started digging, the other coaches who cast doubt with potential recruits, the COVID-19 pandemic or anything else for those ringless campaigns. He just kept coaching, understanding that if he mowed enough season-length lawns, he would finally get it straight again.

After the Jayhawks handily beat Villanova to reach the national championship game, it seemed not only fair, but pertinent, to wonder: After everything, had Self considered whether he might not get back to the pinnacle of his sport? He started his answer by acknowledging the stretch but quickly pivoted to this team and the experience on his roster. He argued his players tipped Kansas basketball from very good back to its birthright—national champions, once more.

And so, in several relevant and perhaps stomach-churning ways, the 2021–22 Kansas Jayhawks present the perfect NCAA champion for these scandal-marred times. Perhaps this team, from all the candidates over all the seasons, will be remembered as the poster child for one particular time period—the era of asterisks in college sports.

Kansas should not be presented as some major outlier. It is not the only university, or even one of a handful of powers, to plow through a special season with a backdrop awkward fails to capture in full. Just look across the court at North Carolina, a university not far removed from an academic fraud controversy. The current Jayhawks should not be entirely tethered to sins of the program’s past that remain in dispute and without resolution. They fought through this season. They overcame injuries. They won those games. They became champions of their conference and sport. Yes, the anvil still hangs over them, ready to dent the trophy that will be added to Kansas’s increasingly full case. But they still won something the past teams since 2008 had lost.

And yet, while perfect captures the juxtaposition of the scandal and a championship, it extends to everything else, too. It frames this Kansas season in relation to the lost one, the ever-crowded transfer portal and, amid a sea of uncertainty unrelated to the investigation, the value of experience in modern college basketball. Kansas is perfect in its imperfections, which makes it an ideal champion for the most flawed stretch of recent human history, sports included.

Just like its recent seasons, and much like throughout most of this season, the desired result for Kansas would not come easy. Not even Self would have expected that.

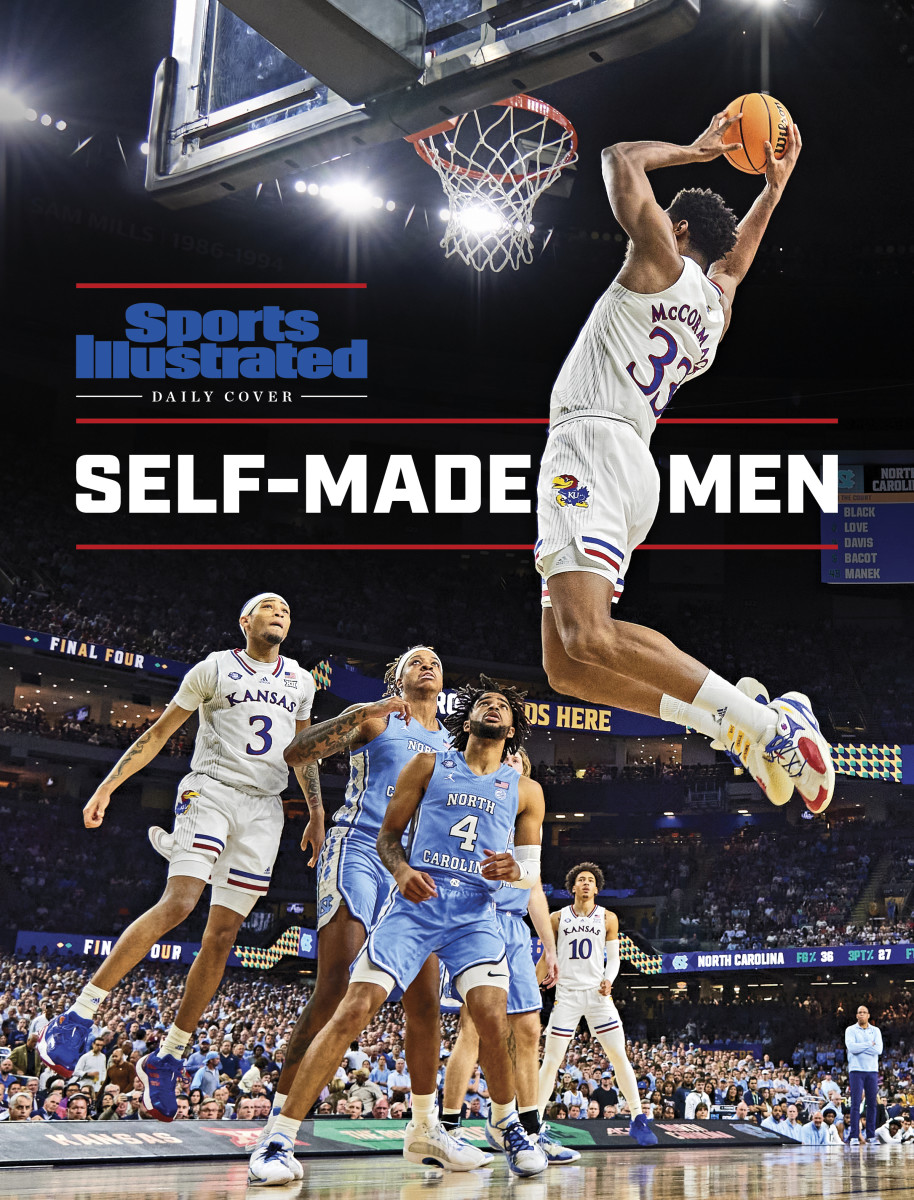

Trailing North Carolina by 15 at the half, teammates asked forward David McCormack why he was smiling. “Keep your head up,” he said. “We’ll be all right.” The Jayhawks then roared back into Monday night’s national title game at the Superdome. That’s why. They made it close, tense, the kind of affair that spared not a single fingernail on a nervous hand.

The final minute of game clock unfolded over what seemed like an hour of This Is Us–level drama and suspense. McCormack—who else?—had given Kansas a late 70–69 lead. For the record, he did see the two open teammates set up on the perimeter when he grabbed an errant shot. But even with his adrenaline surging, he remembered something Self often reminded him: Snatch the rebound with two hands … keep the ball high … go right back up. He did just that.

North Carolina’s Armando Bacot, the 6'10" forward who filled March and April with NCAA tournament heroics, took the ball, drove inside, drew contact but not a foul and missed an off-balance lay-in. Bacot did not rise immediately and, when he did, he struggled to stand. But officials did not stop the clock at first, not until 38.5 seconds remained.

By then, Kansas held both possession and the lead. The Jayhawks threw the ball back inside to McCormack, who pushed his defender even deeper into the paint and then flicked in the most important jump hook of his life.

UNC sped back down court, trailing by three points, and proceeded to hoist a pair of attempts from beyond the arc that met rim rather than net. Still, forward Brady Manek grabbed another offensive rebound, only to lose control of the ball, which landed out of bounds and shifted the possession back to Kansas. And before KU could dribble into more foul attempts, guard Dajuan Harris inadvertently stepped out of bounds with his left foot.

North Carolina had one more chance with 4.3 seconds to go. The ball went to Caleb Love, who misfired on another triple, after Christian Braun switched onto him and stuck a hand in his face. This sent the Jayhawks soaring into a long-awaited celebration. The final score read 72–69, with five KU players in double figures and the greatest comeback in NCAA tournament title game history in the books—but it failed to account for the ending of a title drought that spanned more than a decade.

The Jayhawks’s actions took care of that. Ochai Agbaji ran around the court, as if looking for someone to hug, eventually settling for the KU radio crew. Confetti showered the Jayhawks, many of whom stumbled around, trying to collect loose strands. Some Kansas players fell backward onto the court (McCormack), others yelled at ghosts who had ostensibly counted them out (Braun), while still others searched for family who made this moment possible (Remy Martin, who kept asking, “Where’s my dad?”).

For those who remained inside the Superdome, who cheered and hollered and hugged, how the rest of college basketball might feel about this Kansas title had been shelved, for now. What mattered were the scissors held in the hands of the champions who were slicing into nets. The perfectly imperfect NCAA champions refused to let anything diminish their jubilation.

Hinson arrived at Topeka in the spring of 2008, shortly after the Jayhawks toppled Memphis to ensure Self would join college basketball’s championship tier. That KU team showcased seven players who would make the NBA, from starters like Mario Chalmers, Brandon Rush and Darrell Arthur, to backups like Cole Aldrich. They won 37 games, lost only three times and leaned on balance rather than one star, pairing four scorers in double figures with an elite defense.

The new assistant was almost embarrassed by his experience to that point: three stints at Oklahoma high schools, Oral Roberts, Missouri State. But Hinson wasn’t self-conscious about his administrative role, first as the director of external relations and later director of operations for Self’s program. He wanted to understand how the heart of a major power came to beat. On his first day, Self kicked off another season of great promise by showing a highlight montage of his one shining moment. Hinson cried more than the returning players. “Like a baby,” he says.

He was finally part of the institution known as Kansas basketball, its grand tradition summarized by that phrase. Nothing else needed to be said. Hinson studied the championship teams behind the banners that hung in Allen Fieldhouse (2008, 1988, ’52). He learned more than he already knew about luminaries like James Naismith, Phog Allen and W.O. Hamilton. No other program could claim that its first basketball coach also invented, well, basketball. But Kansas could, with Naismith.

Hinson noticed early on what Self understood as his primary duty: to uphold a tradition as long and historic as the one that landed in his hands. The coach never asked his players to be those players. He expected them to be only the best versions of themselves. For sure, Mount Self erupted with striking regularity, but that signaled what lingered deep inside. Self was his father’s son. He always would be.

More layers. More peeling.

In the 11 seasons after Kansas won that championship, the Jayhawks lost in the Sweet 16 (2009), the second round (’10), the Elite Eight (’11), the national title game (’12), the Sweet 16 (’13), the third round (’14 and ’15), the Elite Eight (’16 and ’17), the national semifinals (’18) and the second round (’19). Most programs would love to experience that sort of postseason “failure.” But Kansas is not like most programs.

After 11 seasons of so-close-but-so-far chances at another championship and everything else (like the notice of allegations), Self and his Jayhawks rounded into top form in early 2020. They featured a dominant, explosive guard in Devon Dotson; a bruising, shot-swatting center in Udoka Azubuike; plenty of size in Azubuike, McCormack, Tristan Enaruna and Silvio De Sousa; and an emerging talent in Agbaji, who hailed from nearby Kansas City.

Kansas had built its next champion, the title all but assured, at least in the collective mindset of a program that would know. The Jayhawks upset top-ranked Baylor on the road in mid-February of that year and finished their regular season with 16 straight wins, the last on the road against stingy Texas Tech. They were ranked No. 1 in the polls and had overtaken the top slot in KenPom’s analytic metrics by a wide margin, the gap between them and second-ranked Gonzaga as wide as the gulf between the Zags and the seventh-rated team.

The conference tournaments began, but only briefly, soon to be halted and erased by the worldwide spread of the novel coronavirus. McCormack has never forgotten the worst moment, when he took that fateful phone call inside his hotel room, already in full uniform, ankles taped for the Big 12 tournament opener. The Jayhawks, all dressed up with nowhere to go, went downstairs. They took team pictures, while hugging, lamenting and crying, as they started to realize how serious the pandemic had become. Soon after, the season was canceled, all their work for naught.

Throughout this week, Self fairly pointed out that COVID-19 had impacted every team in every sport on every level. But for his veterans who remained, who can compare then with now, questions lingered. How many college basketball teams that season had, per their own ratings, the country’s best big, best guard and best defender? How many held onto the exact late-season momentum that often defines a title run? How many would have been the No. 1 overall seed with the easiest path forward?

McCormack eventually dispensed with all pleasantries. He said, point blank, that team was better than this team, adding the 2020 Jayhawks “would have won it.”

Last season, Self continued to nurse an environment that focused his players’ viewpoints on front windshields rather than rearview mirrors. He fought back against the urge to linger on the nebulous “drought” that hovered over their efforts. He kept coming back, kept coaching and assembled another team for March.

Surely, some of the seeds Self planted in 2020–21 grew into this season’s championship stalks. But there was little, if any, immediate payoff. Those Jayhawks lost nine games, including five of seven near the end of the regular season. They didn’t win the Big 12 regular season (won by Baylor), conference tournament (won by Texas) or national title (Baylor, yet again), and were flat-out flatlined by USC in the second round of the NCAA tournament. The lopsided 85–51 result didn’t do justice to the caliber of rout the Trojans delivered on national TV.

Self admitted as much that night, providing an honest assessment for where his team needed to improve, ticking off weaknesses that needed to become strengths. Kansas needed to get more athletic, bigger and longer to survive, let alone snag another championship, which was hard enough to win with those elements already in place.

So began the closest thing to a Kansas rebuild in recent history. He started with his two true seniors, Agbaji and McCormack, who could remain in the starting lineup and imprint the physical, relentless brand of basketball Self wanted the Jayhawks to play. When Self brought their class to Kansas, the hype centered on Quentin Grimes and Dotson, not two future program pillars. Other critical players returned via distinct routes tied to the pandemic or the heightened activity in the transfer portal. Self would need them, too.

Forward Jalen Wilson originally committed to Michigan and stuck with the Wolverines until his future coach, John Beilein, left for the NBA in 2019. Beilein’s departure instantly made the four-star recruit one of the most sought-after players available. Of all the choices, he visited two programs: Kansas and North Carolina. He chose KU, having “always wanted to play for Kansas,” then provided an immediate impact that grew each season. “It’s crazy how it all worked,” Wilson says. “It really is.”

That same year, late-developing guard Dajuan Harris balled out at the EYBL Peach Jam. Harris’s teammate on the AAU circuit, Braun, already played for Self at Kansas. Between Braun’s lobbying, Self’s ability to redshirt Harris in 2019–20 and what the coach saw on film, he took another chance.

Self came into this season with better versions of all those players. Eventually, the coach realized something: He already had much of what he believed his previous teams lacked. “Bigger” came in the advanced role of McCormack, who played like a giant at a muscled 6'10", along with size at key positions in Wilson (6'8"), Braun (6'7") and Agbaji (6'5"). “Tougher” could be gleaned by his team’s collective experience, highlighted by a roster with two seniors and five “super seniors” granted an extra season because of the pandemic.

Beyond developing his current players, Self also addressed the “more athletic” concern by adding Remy Martin, a dizzying guard from Arizona State who had made All Pac-12 first or second teams in each of the previous three seasons. Martin was a super senior himself, one who turned down the NBA and a few million for one reason: “to play for a national championship at Kansas.” He fit perfectly alongside Harris to give the Jayhawks a backcourt stuffed with athleticism. They could force a higher, breakneck pace when needed and score in torrents of drives, twists and shots created whenever the set offense had stalled.

As Self watched Martin in early practices, he saw the player that made everything, and everyone else, work together. The coach also could make out the faint imprint of an unlikely championship roster taking shape.

Experience came to matter more than anything to Self. As college basketball evolved, he joined coaches at elite programs in trying to secure the even-brief services of the best high school prospects. But between the transfer portal and pandemic-specific adjustments, even the most talented teenagers seemed to struggle in March, while programs with more veteran players were the ones primed for late-season runs.

KU team outsiders might not have pegged this as a national-championship-caliber team, and perhaps that’s the reason these Jayhawks did the unexpected. Maybe that was the entire point.

As the national title game drew closer, the greater Kansas City area wrapped its collective arms around Agbaji, their favorite son and homegrown talent, the Jayhawks’ latest superstar. At Oak Park High, they dedicated a day in Agbaji’s honor. Throughout the North Kansas City School District, staff and students were asked to wear Kansas colors, a mix of blue, crimson and signature Jayhawks yellow and gray. They held rallies and viewing parties. Meanwhile, his sister, Orie, reminded her younger brother to stay focused, to not lose in a national title game like she had playing volleyball for Texas.

Her brother’s path might be the most improbable Kansas story of all. He was born in Milwaukee, and his family moved to Missouri. He played soccer and hoops before growing nine inches between his freshman and junior years of high school, when he started focusing on basketball full time. He didn’t receive a Power 5 scholarship offer until his final semester, and chose Kansas over Texas A&M and Wisconsin. He planned to redshirt but didn’t. Looking back, Self laughs at the year of eligibility he “burned” for Agbaji. Had he not, Agbaji would have surely departed anyway, en route to the NBA. Instead, Agbaji embodies this Kansas season, from the opening victory against Michigan State to the national championship triumph.

All year, Braun says the Jayhawks looked to Agbaji and his relentless pursuit of a title to help drive them. Kansas saw its star toil in the Arizona heat for private workout summer sessions before the season. KU noted how he never shifted the spotlight onto himself, how he stayed after to help his teammates overcome what ailed them, picked up his scoring when the injuries started piling up and became more of a distributor again when injured players made their way back into the rotation. After Kentucky embarrassed Kansas in January, the Jayhawks once again turned to the same place. Two games later, Agbaji scored 18 points and grabbed nine boards in a shellacking of defending national champion Baylor.

Self continued to remind his players: Every goal they wanted to achieve remained in front of them, still possible, but they would have to fight for each and every one. He harped on playing better defense in practices, then watched as the rest of his team lined up behind his seniors, Agbaji and McCormack, like they were ready to scrap for the remainder of the season.

McCormack focused on imparting how his team would play, which he describes as “a game of aggression, a game of bullying, of how bad you really want it.” He leaned into one of Self’s favorite sayings: “Make other teams play worse.” That meant tight defense, never taking a step backward, imposing a collective will. For years, through the pandemic, a nasty foot injury and unrealized potential, McCormack had wondered what exactly Self was trying to bring out of him. Late into the season, he finally realized: this.

As February turned to March, Kansas dropped back-to-back road contests against Baylor and TCU, each by 10 points. The Jayhawks rebounded, overtook rival Kentucky for the most wins in any one program in the history of college basketball and cemented itself as a legit contender and No. 1 seed.

Agbaji, a player who teammates insist deserved to win everything, actually won pretty much anything a college basketball star can in a single season: Big 12 Player of the Year, the Big 12 regular-season and conference tournament crowns, and tournament MVP honors. He became a first-team All-American and a true national player of the year candidate. Self was reminded of Danny Manning, the archetype of Kansas basketball, who, in 1988, won all Agbaji has and more—most notably a national championship. Could Agbaji, who Self described as having “a chance to have the best year at Kansas since Danny,” do the same?

The first half of the latest national title game showcased Kansas’s progress this season—and its lingering flaws. The Jayhawks jumped to early advantages behind McCormack and Agbaji scores that put them ahead, 9–3 and 11–5. But a potential double-digit win for Kansas quickly turned the other way.

With 10:28 left in the half, KU led 18–14 after Martin sank a three-pointer that momentarily stopped the reeling. By halftime, KU trailed 40–25. The Jayhawks had six turnovers and missed almost 70% of their shots. In those 10 minutes and 28 seconds, UNC outscored the Jayhawks by a staggering sum of 26–7. “Be better,” Self told his team at halftime.

Hinson sent a text message to Sports Illustrated at halftime, unprompted: [Self is] not panicking right now. … He’s calming those kids … just like his dad would have. … Just watch it’s going to be a great second half.

True to that missive, Kansas shot back into the title game. Harris ramped up his defensive pressure, and teammates followed suit. McCormack slammed home a dunk. Braun shoved in a putback. Wilson drove for a layup. On and on it went, the deficit slimming over the first five minutes of the second half, until North Carolina’s lead had shrunk to 45–38. A jumper from Harris soon cut the hole to four points. What stood out: It wasn’t one player that pushed Kansas, but all of them, a team that needed every piece, right until the end.

More layers, albeit of the comeback variety. More peeling.

Here came Kansas basketball in a single sequence: Harris steal, outlet to Agbaji, slick pass to Braun, bucket. When the Tar Heels called a timeout with 12:41 remaining, they led by a single point.

More drama, too. Agbaji missed a three-point attempt for the lead, Puff Johnson dunked at the other end and Agbaji evened the game with a drive, a foul and a free throw. If a tie at 50 seemed unexpected, consider the vertiginous nature in which Kansas pulled ahead: another Martin triple, another Wilson drive, another Wilson free throw. In a blink, KU led by six.

Michael Jordan watched, entranced, inside the Superdome. So did Paul Pierce and other KU royalty. All hoped for an epic finish that seemed quite possible with about eight minutes remaining.

For brief moments, it seemed like Kansas might pull away, but North Carolina continued to close deficits. The waning seconds had everything: turnovers, missed layups, made free throws, fearless attempts that splashed through nets, an air ball, lead changes, momentum swings, tears, anger, and perhaps even all five stages of grief.

All of which set up an improbable ending to the most unlikely of championship seasons.

What’s funny, revealing and strikingly full circle is this: Self’s best player (Agbaji), most improved one (McCormack), toughest one (Harris, who arrived on campus after his father and younger brother were killed in separate incidents), most steady one (Braun) and newest one (Martin) all remind the coach of his father in precisely the same way.

Self long loathed one statement Senior drilled into him from birth. Don’t worry about the mules; just load the wagon. Once he became a coach, he loathed it no longer. It explained him, on and off the court, in every season and in this improbable year most of all. Agbaji’s rise and McCormack’s development came from loading the wagon. Same for Wilson, Braun and Harris, regardless of how they arrived in Lawrence. Same for Martin’s injury, which took place on that terrible night against Kentucky and sidelined him for almost a month.

How did Kansas keep finding itself this season, where previous teams with more talent had lost their way? How did Self, with sanctions looming and his father’s death ever-present, tell his team after its Elite Eight win against Miami that its best moments were yet to come? Because each loaded the damn wagons and went back to load again. That’s why.

The wagon loaders, Martin says, “locked in,” and kept loading until their collective aim became less about any one moment from the season. Not the blowout defeat that sounded alarms; not Martin’s injury; the odd loss at TCU; the speech Agbaji made after that defeat, calling for more effort, pleading, we can’t let this happen again; his own late-season struggles; Coach K’s final year; the other fallen No. 1 seeds; Martin’s new role, sparking Kansas off the bench; or McCormack’s muscling Villanova right out of the Final Four.

They bonded with late-night video game sessions, or while taking in Chiefs home games or over meals with teammates. And through constant reminders delivered from their elder statesmen of what had been lost two seasons ago that could now be reclaimed.

McCormack became a human chorus of “don’t take basketball for granted.” Self, in a trying year, joined him. The coach’s mom, Margaret, started to return to games, reminding her son of his father, the foundation they built together and how moments like those from 2008 are never guaranteed to happen again. Such is the fragility of sports. Self said he had random, brief periods of self-reflection he wouldn’t have allowed himself in other years. He said he saw these players “grow up” right in front of him, becoming a better team for its infusion of experience. He couldn’t do anything about 2020 or ’21, or alleged transgressions that could soon be penalized, but he could elevate these Jayhawks to the finish they either deserved, in the eyes of the program and its fan base, or didn’t deserve at all, in light of the investigation.

The unexpected development lay within him. As the man in charge of Kansas basketball, for better and worse, Self realized what by then seemed obvious. This group, in all its imperfections, had changed him, reminding Self why he coached, why it mattered and why it always would.

As the on-court celebration wound down, Self and his players climbed atop a stage and snapped an entirely different kind of team photo. Only those who remained from 2020 truly understood the difference at that moment.

The key to another national title was embedded in the human element, the gap between what Kansas had done and what it would do. But that chasm could be bridged by only Self and his current team. The bridging would take place on a sensitive fault line, for players and coaches and everyone, really, who had been unmoored by two years of peak uncertainty.

Late Monday, early Tuesday, Self’s thoughts drifted back to the inevitable, his dad. He believed Senior would be “very proud of this team, because he knows, without question, they earned what happened tonight.”

“When Bill takes off his shirt, there’s no ‘S’ tattooed on his chest,” Hinson says. “He’s not Superman. There will come a time when he has to deal with his grief. A time when he’s alone. But that time is not now.”

Keep that sentiment right on rolling. Forget basketball. Forget accolades. Forget the lost season and the long wait between championships, along with titles fumbled and seized in New Orleans. Forget Self’s place in a new coaching landscape, with Roy Williams retired, Mike Krzyzewski retiring and Jim Boeheim and others to soon join them.

Forget, momentarily, the sanctions that are likely coming. Forget even the framework, the perfect champion for these imperfect times. The story of this Kansas season and its coach, Hinson argues, is as old as time. It’s about a father who meant everything and the son who still wants to make that father proud, one loaded wagon—and national title—at a time.

More College Basketball Coverage:

• UNC’s Resolve Pushed to Limit in Bruising Title Loss

• Way-Too-Early Men’s Top 25 for 2022–23 Season

• Top 10 Moments of Men’s NCAA Tournament